Why has the Eurozone emerged as the new epicentre of the global financial crisis, when its origins—the famous subprime mortgages—were American?footnote1 And why, within Europe, has Greece proved to be the weak link? The starting point for any adequate answer is the recognition that what we have been experiencing for the last five years, since the onset of the credit crunch in August 2007, is a single crisis of financialized capitalism. The Greek events are only a sequence within it. Despite the concerted efforts of the governments of the G20, the intervals of recovery have been no more than short-lived episodes; the political measures taken have proved powerless to overcome the strong depressive tendencies at work. The crisis has struck the heart of the financial system—the banks—but it is systemic, affecting every part of the economy: banks, firms, households, states.

Its origins lie in the massive global imbalances built up since the East Asian crisis of 1997–98, which marked the world economy’s entry into a new, inherently unstable, accumulation regime.footnote2 In the West—above all in the us, and to varying extents across the eu countries—this involved the intensification of the drive for shareholder value, which set high profitability thresholds for investment and exerted intense pressure on labour, delinking productivity and wage increases. With median wage growth depressed, and growing inequalities in wealth and incomes, the dynamic demand required by the shareholder-value agenda was provided by the expansion of credit, supported by low interest-rate policies; debt-based household spending allowed consumption to grow at a faster rate than incomes and wages. In the East, by contrast, the financial turmoil of 1997 and the imf’s subsequent ham-fisted interventions brought home the danger of relying on rent-seeking Western capital. Countries that had been burnt by the East Asian crisis—which rapidly spread to Russia, Brazil and Argentina, also affecting Germany and Japan—sought to defend their economic sovereignty by building up dollar-denominated balance-of-payments surpluses through export growth. The entry of China into the world market as a major exporter hugely amplified this trend. The historic direction of capital flows, from the West to the emerging economies, was now reversed: billions of dollars flowed from China and other exporting countries to the us, fuelling the vast expansion of credit that was further multiplied by the growth of securitization and derivatives trading, centred on the big banks.

These imbalances were equally present within the European Union, exacerbating the divergences between member states; large Eurozone banks were also laden with bad debts. In addition to this, however, the crisis exposed a series of deep structural flaws in the constitution of the European single currency. What follows will examine these imbalances and structural defects, before discussing the unravelling of Greek public finances, the options currently facing Athens and the spread of the crisis in the last quarter of 2011 to all the Southern countries—leading up to the deteriorating macroeconomic conditions across Europe in spring 2012. The twin sovereign and banking crises, dragging down economic activity, are slowly impinging upon the whole world. I will conclude with a characterization—and critique—of the German approach to the Eurozone, and raise the question of what measures would be required to place the eu on a path to sustainable growth. First, however, it may be useful to take the measure of the public and private debts that have mounted across much of the continent.

Half measures

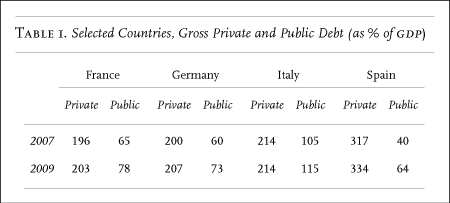

The eu single market created an integrated financial space, open to capital flows. The large European banks became global operators. They played an active part in the expansion of debt and toxic assets in the us and, when the crisis broke out in 2007, found themselves in a position comparable to that of the American banks. But the French, German and Spanish governments initially allowed them to freeze their bad debts, rather than forcing them to restructure. The banks also loaded up on Eurozone public debt in the years that followed—raking in considerable profits for themselves in the process, by borrowing at practically zero rates and buying government bonds paying 3 to 4 per cent interest at the time of the 2009 stimulus plans. During the first two years of the crisis, as the 2007 credit crunch deepened into the banking crisis of 2008, the fall of Lehman Brothers and the global economic contraction of 2009, the Eurozone states saw private debt as a percentage of gdp continue to rise, while gross public debt—that is, without factoring in assets—also soared with the recession (see Table 1).

In 2007, before the crisis began, France and Germany had comparable levels of gross private debt (196 and 200 per cent, respectively) and gross public debt (65 and 60 per cent), whereas in Italy gross public debt had reached 105 per cent, a particularly high figure; in Spain, gross private debt had reached the astronomical level of 317 per cent, essentially accounted for by real-estate developers, mortgage borrowers and regional savings institutions—the cajas—in the context of the property bubble, while public debt was a more modest 40 per cent. Two years later, it might have been expected that the transfer of debt to the public finances would have reduced private exposure. But by 2009, on the eve of the European crisis, quite the opposite had happened. In France and Germany, the supposed paragon of virtue, gross private debt was now 7 points higher than in 2007, while in Spain the figure had risen by 17 points. Of course, the contraction of gdp that took place during this period automatically increased the debt’s percentage; nevertheless it was clear that public debt had risen without private debt being absorbed. Meanwhile in Greece, by 2009 gross private debt stood at 173 per cent and gross public debt at 115 per cent, climbing to 145 per cent in 2010 (the Greek figures for 2007 are not reliable). In Ireland, the financial sector’s debt was entirely taken over by the state, with the result that total debt reached 806 per cent in 2009, of which 607 per cent can be ascribed to the banks.

In sum, for the Eurozone as a whole, the budgetary stimuli of 2008–09 did not result in a reduction of debt in the private sector. In the us, by contrast, where gross private debt stood at 300 per cent of gdp in 2007, the recapitalization of the banks enforced by tarp, in tandem with ambitious monetary and budgetary measures, brought the figure down to 260 per cent by the end of 2009. Here, then, lies a first distinguishing feature of European Union policy: it is the champion of half-measures, produced by tortuous political compromises. The eu is further hampered by a deep-rooted ideological conservatism with regard to fiscal measures to support demand and central bank mandates for growth. If this approach is problematic in periods of calm, it becomes disastrous in times of turbulence.

Structural flaws

The Eurozone also suffers, however, from deeper-lying structural weaknesses resulting from the manner in which it was constituted. The decision to launch a European single currency was by no means self-evident: integrated economic and financial zones have operated successfully with flexible exchange rates—nafta, or the Benelux customs union, for example. The original proposal for a monetary union in Europe, the Werner plan, had foundered in the 1970s in face of the Bundesbank’s hostility; as an exporter, Germany was fearful of the monetary inflation it was importing from the us as its currency reserves soaked up a torrent of dollars. The impetus was renewed in the 1980s, on the basis of the Single European Act. The 1989 report of the Delors Committee proposed the creation of a single currency and a European Central Bank which would be a joint venture of all the national central banks. It is hard to say whether this project would have succeeded in the absence of German reunification. However, Helmut Kohl’s decision to push for this in 1990 led to a decisive expansion of the Federal Republic’s weight in Europe, altering institutional relations and directly affecting France.

The single currency famously emerged as a political compromise that allowed the French to accept reunification, since it reaffirmed Germany’s deep embeddedness within Europe. One important element of this agreement was Kohl’s insistence that the future ecb would be modelled on the Bundesbank. In implementing this, however, the Franco-German compromise profoundly altered the process of European integration. The original communautaire approach had been dialectical: economic integration led to institutional developments—the European Coal and Steel Community, the Common Market, the Common Agricultural Policy—which would be conducive to greater economic integration, and so on. This was the perspective championed by Delors, in the spirit of Monnet and the other founders of European union. The decision to create the euro marked a change of register, for the currency is not a sector that can be integrated like any other.

This should have been apparent from the 1992 débâcle of Europe’s Exchange Rate Mechanism, which in many respects foreshadowed the crisis of today. The erm obliged member-state currencies to keep fluctuations in their exchange rates within narrow boundaries—plus or minus 2.25 per cent—relative to each other, which effectively meant relative to the Deutschmark. In the early 1990s, the recession that followed the bursting of the us asset-price bubble put strains on several of the erm economies that they were unable to handle within the rules of the system. The shocks were exacerbated by the economic effects of German reunification, which put pressure on the public finances of the Federal Republic and took interest rates to record highs just as the repercussions of the American recession began to be felt in Europe. Italy, grappling with high public debt and stubborn inflation, was forced to devalue, followed by Britain in September 1992. With the support of the Bundesbank, the French franc managed to stay within the erm. But when financial-market speculation was renewed the following summer, the erm’s limits had to be relaxed to 15 per cent, effectively putting an end to it.

The lessons of this episode were brushed under the carpet by political leaders at the time, and are rarely recalled today in analyses of the current crisis. Nevertheless, the modus operandi of the erm’s fixed exchange rates, tying the other European national currencies rigidly to the Deutschmark, was in many respects a rehearsal for full monetary union. Like the erm before it, the single currency may be viable within the existing rules as long as there is calm in the financial markets, but becomes inoperable in periods of crisis. The euro is essentially a foreign currency for every Eurozone country. It binds them to rigidly fixed exchange rates, regardless of their underlying economic realities, and strips them of monetary autonomy. In this sense the euro today functions in much the same way as the dollar did for Argentina between 1991 and 2001, when the exchange rate was fixed by the Constitution itself at one peso to the dollar.

Put another way, as a system the euro is akin to the gold standard: an external currency whose overall supply was out of reach of national governments, but fiat money nonetheless, trusted within the financial community because the rules of convertibility were deemed inviolable. After the eruption of the financial crisis of October 1929, the gold standard lasted less than two years. The spread of the crisis from the us to Europe, through the contraction of trade and credit, entailed bank failures in central Europe in May 1931. The lack of cooperation between governments and the interruption of international funding led to the fragmentation of banking along national lines. The coup de grâce came in August 1931 when sterling broke convertibility and devalued sharply. Now, seemingly, the Eurozone banking system is fragmenting, threatening the very existence of the euro.

Divergent development

A second structural problem exacerbated by the form that monetary union has taken is the underlying heterogeneity of the Eurozone. The Maastricht criteria for entry centred on indicators for inflation, public deficits, exchange rates and long-term interest rates in the candidate countries, which were supposed to converge towards the lowest levels. Long-term interest rates did in fact converge towards German levels from 1996; indeed they fell spectacularly in a number of countries which were otherwise far from meeting the Maastricht criteria, initially due to markets’ expectations. They then fell very rapidly after May 1998, when the European Council ratified the list of countries eligible for admission. In Spain, the spread between the 10-year interest rate on public debt and the German rate fell from 5 per cent to zero in the space of a few months. Not only states but all economic actors benefited from the lowered cost of credit; the ability to borrow cheaply produced massive capital inflows in countries where high interest rates had long made credit scarce.

The question that should have been asked is: what purpose is all this capital going to serve? Official doctrine—the so-called Lisbon strategy, which proclaimed in 2000 that Europe would be at the forefront of the knowledge economy by 2010—envisioned a virtuous circle: the free movement of capital would improve competitiveness, net exports would increase and eventually compensate for the initial rise in debt, without the need for any coherent industrial strategy to be drawn up. In the first years after the euro was launched—as an accounting unit in 1999, and as coinage in 2002—everything seemed to be going as planned. There was a massive influx of capital, not least because this was the moment when global credit really began to take off, thanks in particular to financial engineering.

But Brussels’ economic logic quickly proved false. A flood of capital went to the economies that had possessed the highest interest rates before entering the single currency. However, the constraint of fixed exchange rates undermined the profitability of the Eurozone’s exporting firms at precisely the moment when East Asian countries—which had emerged from the 1997 crisis with under-valued exchange rates and wished to reduce their debt burdens—were mounting a commercial offensive in Western consumer markets. French and Italian banks made profitable loans to local financial institutions, which in turn fuelled consumption and property speculation. In Spain, where French and German banks helped channel funds into a gigantic housing bubble, construction and the sectors subcontracted to it came to account for as much as 25 per cent of employment; services developed in parallel, while the industrial base atrophied. Rapid growth was based on the steady escalation of property prices, which fed the growth of credit and underwrote household borrowing; credit-based consumption drew in rising imports of manufactured goods, which brought widening current-account deficits and a price inflation that undermined competitiveness. Growth became dependent upon ever-greater injections of foreign capital, further exacerbating the current-account deficit. As in all countries where financial excesses generated speculative bubbles and inflationary consumption growth, the bursting of the bubbles left a massive overhang of private debt.

The trajectory of the creditor countries was very different. Germany, in particular, spent the 1990s dealing with the contingency costs of reunification, which made it rather easier for neighbouring economies to converge with its indicators. Germany entered the Eurozone in 2000 with an unfavourable exchange rate and a current-account deficit; its growth was brought to a halt in 2002–03 by a severe banking crisis. High wage costs had eroded industrial competitiveness and the economy was sliding towards stagnation—one reason why the German property market did not join the cycle of rising prices that many other developed countries experienced with the credit flood of the early 2000s. (The housing market also remained relatively flat in France, where borrowers were subject to fairly strict solvency regulations and securitization of credit was not allowed.) The Schroeder government responded in 2003 with a drastic labour-market reform; wage growth was brought to a halt and industrial production restructured, with many processes outsourced to Central and Eastern Europe. The gains in competitiveness due to low unit-wage costs were sustained throughout the rest of the decade.

In other words, the 2000 Lisbon strategy, aimed at convergence, led instead to a widening gulf. The economic heterogeneity of the Eurozone countries was accentuated, in major respects, by the financial logic that ensued from the creation of the euro. The often-made comparison with the us remains apt: there, divergences between the different states of the Union are tempered by the mobility of the American workforce—which, for obvious reasons, Europe has been unable to achieve to anything like the same degree—and by transfer mechanisms at a far more significant level than anything that obtains between the countries of the Eurozone.

Monetarist model

The Eurozone is further handicapped by its institutional design, dominated by the ecb, which constitutes the sole federal entity within a non-federal Europe. This contradiction lies at the heart of the present crisis. The conceptual underpinning of the euro is provided by monetarism, which holds that the currency is neutral with regard to real economic phenomena. This means that the sole purpose of a central bank is to maintain the stability of the currency’s purchasing power, defined as the inverse of a standard index of prices, statistically constructed as a measure of inflation. Since its mandate does not clash with any other economic policy goals, the central bank can enjoy an absolute independence. This is why the Maastricht Treaty conferred a truly extraordinary status on the ecb. Unlike all other central banks in the world, its legitimacy is not grounded in any political sovereignty; it is not even required to interact with Europe’s governments. Nor does the Eurozone have any other mechanisms for region-wide macroeconomic regulation, combining budgetary and monetary instruments, beyond an arbitrary and uniform limit imposed on the public deficits of this heteroclite ensemble under the name of the ‘Stability and Growth Pact’. The ecb operates in splendid isolation. The aggregate budget of the Eurozone is nothing more than the ex post facto outcome of budgetary decisions made by each country on its own.

It is hardly surprising that this monetarist model was unable to withstand a major financial crisis. The us Federal Reserve was created in 1913 because the banking crisis of 1907—in which the entire American financial system was seen to be dependent on British loans—demonstrated the costs of a currency that was not guaranteed by national sovereignty. In this light, the contortions of the ecb during the present crisis become more understandable. In order to play its role as lender of last resort—a role it cannot escape—it must necessarily make political decisions about which market or financial actor to support. But what legitimates the decisions of a central bank that is not accountable to any sovereign authority? The bonds between a sovereign currency and the national debt are organic. The latter can be understood as a debt owed by the citizens to the nation, the counterpart to the public goods and services that the state as a collective provides for its members. Payment of this debt is a process that extends over generations and depends on the power of taxation proper to a sovereign state. The currency, in turn, can be conceptualized as a debt the nation owes to itself. The link between the state and the central bank, an institution invested with the power to issue currency, is therefore very close: the state guarantees the central bank’s capital and declares the currency legal tender; in return, the central bank is the state’s lender of last resort.

It is in this sense that the euro is incomplete as a currency, for its sovereign guarantor has not been realized. Each Eurozone state is responsible for the capital it has invested in the ecb, but not for its overall solvency; consequently, the ecb is not the lender of last resort for the Eurozone states. This, again, makes the euro a foreign currency for each country. There can be no cooperative policy-making in Europe if the currency is external to all member-states. There is, however, one country for which the euro is less external than it is for the others: Germany. If Berlin were to agree to play the role of benevolent leader—that is, taking on board the interests of the monetary union as a whole, while pursuing its own policies—it might have been possible to arrive at a second-best scenario; but it has done nothing of the sort. Historically, monetary unions have gone in one of two directions: either they have been dissolved—the Latin and Scandinavian unions—or they have moved towards constituting political sovereignty, as when the Zollverein customs union formed the basis for the German Reich. The Eurozone, then, possesses neither a cooperative organization, which would enable forms of collective political action tending in a federal direction, nor a hierarchical organization, which could be lent coherence by a leading country. In normal conditions, the non-cooperative play of rival political interests may reach a functional equilibrium. But in a period of crisis, each country defends its own interests while attempting to benefit from ‘free-rider’ tactics.

The Greek case

This is the context in which the unravelling of public finances in an economy as small as that of Greece could degenerate into a sovereign and banking crisis across the entire Eurozone, posing a threat to the world economy as a whole. As is well known, Goldman Sachs helped the then Greek finance minister, Lucas Papademos, to camouflage the country’s debts in 2001, when Greece entered the Eurozone. Investors in the region welcomed the event, as they had done for the other countries two years previously, and the rating agencies—the so-called compasses for the market—confirmed the quality of Greek debt. A little history might have given them pause for thought. In 1829, when Greece seceded from the Ottoman Empire with the aid of Britain, France and Russia, it was a small country, very poor and entirely rural. It retained a clientelist political system, in which the ability to levy taxes was undermined by privilege and corruption. In the 20th century, the two World Wars had a terrible impact on the country. Nazi occupation from 1941–44 was followed until 1949 by an appalling civil war that bled the country dry. Greece began to get back on its feet under a veritable American protectorate, but the political system was not reformed. Another seven-year nightmare beset the country after the coup of 1967, until the military disaster inflicted by the Turks in Cyprus led to the Junta being booted out of power in 1974. Civilian authority was reestablished in the same conditions as before. Greece was admitted to the European Community, along with post-dictatorship Spain and Portugal, for purely political reasons: to strengthen ‘democracy’, in the context of the Cold War. As a member of the ec, Greece ratified the Maastricht Treaty in 1992; but this was no reason to let the country into the Eurozone. Nevertheless the European Commission and ecb pronounced themselves in favour. Political reasons again came into play and it was held that, since Greece’s gdp was less than 1 per cent of Europe’s, it was unlikely to cause any serious problems.

Yet the Greek state has features that are not found to the same extent in the rest of the Eurozone. The Treasury does not collect taxes on a universal basis, corruption is generalized and powerful private actors dictate policy to the state. Shipowners, for example, constitute an ancient corporation that has been able to look after its interests under every regime. If the capital these shipowners have placed in tax havens were repatriated, the Greek public debt could be wiped out. The Orthodox Church, for its part, is exempt from paying taxes on its immense landholdings. There is a large grey economy, which includes much of the tourist industry, in which workers’ incomes are generally undeclared. Once Greece had adopted the single currency, private and public debt rose in tandem, making the country increasingly dependent on foreign creditors—amid total indifference from the markets, famously supposed to discipline debtors. The abyss was revealed in October 2009, when the incoming Papandreou government announced what many had begun to suspect: the Greek accounts had been falsified. This prompted a market shock, with the Greek public banks the first to be affected; these banks served as a powerful relay for transmitting the crisis to the rest of Europe.

What then unfolded was a double crisis, affecting both the banking sector—and hence the private economy—and public finances. Once the public debt began to look unsustainable, raising the probability of a default, interest rates began to rise. This in turn considerably increased the debt burden and, in a vicious circle, helped expand the volume of the debt while limiting the state’s capacity to support the economy. The rise in interest rates on bonds automatically brought a reduction in their value, feeding a demand for insurance coverage that was expressed in a higher risk premium; this also produced a bubble in the market for Credit Default Swaps, which provide insurance on credit risk.

A series of reversals was at work here. In normal times, the interest rate on bonds determines the premium; in a crisis situation, it is the spread that becomes the benchmark and determines the interest rate. In normal times, the cds market is one of several signals investors scrutinize in order to assess credit risk; but with the onset of crisis, this market turned speculative and began to function autonomously. Some investors started buying cdss on Greek debt even though they did not hold any, in the hope that the rising probability of default would push up their price. Eventually the price of the cdss is factored into the debt, with a snowball effect on the debt burden—leading to a rise in the value of cdss. This caused further contagion, since foreign banks invested in the Greek market began to be viewed as suspect, too. This was especially true of French banks, which had sums equivalent to 40 per cent of their capital invested in the Greek economy as a whole. (Because a default on sovereign debt brings with it a savage recession that would push numerous private actors into bankruptcy, foreign banks’ overall position—the debt they hold from banks, state assets, firms, perhaps also from households, for those with branches in Greece—needs to be taken into account.) It became more expensive for foreign banks exposed to Greek risk to refinance; they therefore began to reduce lending, affecting the economy in their home countries.

This series of chain reactions did not take place spontaneously. It was fuelled by denials from both Greek and European leaders of the possibility of a Greek default, accompanied by the imposition of measures that were bound to render the country insolvent. Since May 2010, the policies inflicted by technocrats from the imf, ecb and European Commission have included 25 per cent reductions in public-sector wages, savage public-spending cuts, regressive tax rises and pressure for large-scale privatizations, which would lead to a fire sale of the nation’s capital. The result has been a drop in gdp of 3.7 per cent in 2010, 5.5 per cent in 2011, and probably between 3 and 4 per cent in 2012. Instead of halting the steady growth of public debt, successive austerity measures had sent it up to 160 per cent of gdp by the end of 2011. Meanwhile, the cumulative recession reduced the current-account deficit from an extravagant 15 per cent to 10 per cent of gdp, but it remained a full 2.5 per cent more than ecb–ec–imf projections. For the Troika, of course, if the figures do not tally with the projections it is the Greeks’ fault, for accepting austerity so grudgingly, and has nothing to do with the collapse in production caused by the plan that Brussels and Berlin imposed.

Options for default

Whatever the outcome of the Greek crisis, the Eurozone will emerge profoundly transformed. Given that the country is insolvent, it faces a default one way or another, whether under the npd coalition or Syriza. Either Greece continues to accept the disguised bankruptcy imposed on it by the Eurozone, through successive ‘assistance’ packages with increasingly harsh conditions, or it decides to cut its losses and announce a unilateral default, implying an exit from the single currency. Yet the treatment of these two possibilities in the media has offered little solid analysis to help assess their consequences. In doing so, there are two obvious precedents to bear in mind: Japan and Argentina. In the first case, Japan—its economy laden with private and public debt after the bursting of the property bubble in 1990—experienced long-term austerity tied to stagnation of indefinite duration. In the second case, Argentina, its currency pegged to the dollar, underwent a massive public debt crisis in December 2001. It defaulted and re-established an autonomous national currency in January 2002.

In the case of a Greek default within the Eurozone, public debts would remain payable, as they are not governed by Greek law; the same would apply to imf loans and the successive loans that partner states made via the European Financial Stability Facility (efsf). As for private debts, Greek banks are exposed to their own state by as much as €30 billion and would immediately go bankrupt. The Eurozone authorities could recapitalize them via the efsf, but this would increase still further the mass of debt to be repaid over time. What would be the long-term consequences for the country, in such a situation? It is one thing to avoid a catastrophe in the short term, another to actually emerge from the crisis. Growth in the Eurozone has been steadily weakening from one decade to the next. The recession that has been underway since the late autumn of 2011 will not help to establish a more dynamic trend.

In early March 2012, the Greek government accepted a new rescue plan of €174 billion on top of private-sector involvement. The so-called voluntary participation of private foreign creditors saw them abandon 53 per cent of their claims, bearing losses that had long been previsioned. However, the continuous attrition of the productive sector reduced productivity as much as wages, so that competitiveness did not improve. Thus the relief was short lived, with the recession deepening and the social climate deteriorating fast.

The Eurozone as a whole is close to becoming trapped on a Japanese-style path: perennially anaemic growth and deflation, which prevent the public debt from decreasing. Yet the Eurozone is not Japan—a homogeneous country with a powerful industrial sector, operating in a dynamic part of the world. Japanese debt is almost entirely financed by the savings of its residents who have accepted low interest rates, keeping the cost of the debt to a minimum. The situation of the Eurozone countries is the opposite: disparate levels of competitiveness, a significant role played by non-residents and interest rates skyrocketing for the indebted countries. For the ‘Japanese’ path to be viable, Europe would need to provide finance for structural investments, along the lines of a Marshall Plan for Greece and the other peripheral economies, aiming to improve competitiveness by raising productivity rather than by lowering wages. Aid to Greece should no longer take the form of loans, which only increase the country’s debt levels and deepen its dependence, to no positive economic effect. There would need to be definitive transfers, dedicated to productive investment, by European structural funds whose use would be planned and monitored. Without such aid, the upshot will be to trap Greece under tutelage in a situation of increasingly harsh austerity, working indefinitely to service the debts incurred by successive rescue plans, while foreclosing any possibility of dynamism in the Eurozone that might provide it with a compensatory external source of demand. Persistently high unemployment reduces the employability and the quality of the workforce; the reduction in capital flows lowers the rate of investment, which leads to difficulties in adopting innovations; spending on education and research and development sink to negligible levels, which blocks any advance in total factor productivity. In short, the economy is irreversibly weakened.

If the Japanese path is impracticable, what about the Argentine option? To opt for the latter is to wager on growth in the long term. It would once again place Greece among ‘emerging market’ countries, and would enable it to apply heterodox political-economic methods. Greece is already visibly exhausted by austerity, and a partial default which does not speak its name will only serve to delay exit from the monetary union. A unilateral exit from the euro is a gamble because it is catastrophic in the short term, but offers hope of a rebound that would place the country on a growth trajectory. This would involve the introduction of a new currency, let’s say the drachma; by this means Greece would regain control of its monetary policy. Ninety per cent of private debt is governed by national law: its restructuring—the ‘haircut’ for creditors—would take place through a drop in the exchange rate. The steps needed to put this into operation ought to be done in a particular sequence, which was not fully observed in Argentina. Athens should not wait until the exchange rate has begun to collapse before converting the debts. Euro assets and liabilities should be re-denominated into drachmas as soon as the decision to establish the new currency has been taken, since monetary reform and the transformation of the financial structure are one and the same thing. A number of steps will need to be taken in a very short space of time: first, the freezing of all accounts, to avoid capital flight; second, instantaneous conversion (the Argentines waited); third, closure of all banks for at least a week, to supply them with banknotes, reconfigure the cash machines and examine their accounts (in the us, the Roosevelt administration decreed an extended bank holiday in March 1933); fourth, the state needs to issue very short-term securities which can serve as promissory notes until the new monetary circuit has been established; fifth, nationalize the banks, which means not only that deposits can be guaranteed, but also that, when lending resumes, capital can be steered towards financing internal production.

What would be the economic consequences of this? The ordeal suffered by Argentina between 1998 and 2001 was very similar to that undergone by Greece since late 2009. Under imf tutelage, Argentina went from one austerity plan to another; the country was mired in permanent stagnation and unemployment reached 16 per cent. The spread on public debt relative to the American interest rate reached 2,500 basis points—more or less the level of Greek spreads relative to German Bunds in autumn 2011—but the idea of abandoning the dollar peg was taboo. Drastic austerity brought a liquidity shortage and parallel currencies appeared in the provinces. Inflation, while contained to some extent by restrictive economic policies, remained systematically higher than in the us and Europe. On 1 November 2001, the government admitted that Argentina’s debt was unsustainable, and asked its creditors to lower the interest rate and reschedule $95 billion worth of bonds. A month later, the government ordered the freezing of bank deposits—the corralito—and put in place drastic foreign-exchange controls. The dollar peg was not eliminated until 6 January 2002, however, when the incoming government took a wager on ‘pesification’—the forced introduction of the peso—and de-dollarization. The delay was a mistake, because the currency shortage and suspension of financial contracts that had taken place in the meantime brought trade to a halt.

The immediate effect of this strategy in Argentina was a severe recession, and one would expect the same in Greece. Given the closure of capital markets, the current-account deficit would need to be absorbed directly, since without aid from Europe there will be no way to finance an increase in external debt. The Greek current-account deficit is 10 per cent of gdp, and the country’s industrial base is weak and undiversified. The situation would thus demand a severe depreciation in the exchange rate, which in the short term would mean a drastic drop in imports. The drachma might have to depreciate by around 70 per cent in order to cancel out the current-account deficit. In Argentina, which had $100 billion worth of sovereign debt, the depreciation reached 64 per cent.

In these conditions, inflation was at first very high, and there was a considerable reduction in real incomes. ‘Pesification’ led to a 15 per cent drop in imports over six months. In the first half of 2002, Argentina experienced a contraction of 15 per cent and 30 per cent inflation. But after six months, the situation began to improve. imf and World Bank economists were predicting hyperinflation and rejection of the new currency—that is, ‘wild’ adoption of the dollar in everyday transactions. But what happened was the opposite. There was mass acceptance of the new currency and a rapid drop in inflation, which fell to 3 per cent by the end of 2003. The exchange rate stabilized at a highly competitive level: 3.6 pesos to the dollar. The rebound in production was equally remarkable: a 17 per cent rise over two years. The exchange-rate depreciation brought a boost for manufacturing exports, while global prices for raw materials, of which Argentina is a net exporter, also soared. These developments combined to produce a huge improvement in the balance of trade, such that the current-account balance went into surplus and Argentina accumulated currency reserves. With the resumption of growth, the government could post a primary budget surplus of 2.3 per cent in 2003 and 3 per cent in 2004.

The crucial step for Argentina was the restoration of monetary sovereignty. In the case of Greece, a rebound in exports would affect tourism, agricultural production, freight, business services; the return of profitability thanks to the fall in the exchange rate might encourage foreign firms to set up there. In other words, the country would gain competitiveness through an offensive strategy and not through the attrition caused by lowering wages. To adopt this course would be a gamble, but it is otherwise hard to imagine Greece achieving the conditions for long-term growth. While the prices of goods produced abroad would rise, the country’s longer-term prospects would brighten. Overall, such a wager would be in its interest, if all positive alternatives remain blocked by Brussels and Berlin.

What would be the impact on the Eurozone of a Greek exit? Or, to pose the question another way: how would it differ from the permanent provision of successive emergency loans to Greece, since the measures envisaged can only keep it in a lasting state of dependence? In either case, the immediate problem for Greece’s partners is to avoid contagion spreading to the rest of the Eurozone, bringing with it a liquidity crisis that could push Spain, for example, into insolvency. Only an explicit commitment of the ecb to support the weaker economies of the Eurozone can put a stop to market pressure on their bonds, a necessary first step in any longer-term solution. Some commentators argue that the risk of contagion would be significantly higher if Greece left the euro since this would create a precedent, scaring investors; the whole of Europe would be plunged into severe recession. But as the spreads on Italian, Spanish and French bonds clearly reveal, contagion already forms part of the market’s expectations. If the long-term financial costs for the Eurozone are therefore likely to be roughly similar in the two scenarios, their timing will be different. If Greece re-establishes a sovereign currency there will be an immediate loss for its Eurozone creditors, when euro-denominated claims are converted into drachmas. If Greece retains the single currency, the costs of the ever-increasing sums that will need to be meted out by the ecb, European Commission and imf to enable it to do so will be staggered over the longer term.

The Eurozone and the world

Since May 2012 the dual sovereign and banking crises have gained momentum. Sovereign-bond spreads have been rising in Spain and Italy. After muddling through with government guarantees—typical of the European forbearance practised by national regulators towards their banks—the latter are under pressure to deleverage by €2 trillion over the next two years, according to an imf estimate. Cross-border liabilities are therefore shrinking fast, renewing the threat of a credit crunch just six months after the ecb launched the mammoth Long-Term Refinancing Operation (ltro) to avoid an earlier one in November 2011. Deposits have continued to leak from Spanish banks, more than 2 per cent a month since March 2012. Already spending in the private sector is plummeting in debt-laden countries. Italy has been in recession for three consecutive quarters, with unemployment rising and purchasing power on the wane: private consumption fell by 2.4 per cent and gdp by 1.3 per cent in the first quarter of 2012. In Spain real-estate prices are tumbling, triggering waves of foreclosures. Household financial stress is starting to undermine a legacy of consumer-debt overhang. Combined with an export slowdown, the slump in domestic demand might lead to a loss of 3 per cent annualized gdp growth in the second half of 2012. The worsening recession in Southern Europe, coupled with greatly reduced steam in world trade, is impinging upon the German powerhouse, leading to much lower growth in manufacturing. The weakening macro-economy is feeding back on the financial crisis; commitments to reduce fiscal deficits relative to gdp cannot be fulfilled. Sovereign and public debts are likely to rise 15 to 20 per cent before the end of 2013, sowing more acrimony in government dialogues.

Moreover, the situation of financial uncertainty and recession in Europe has a corrosive impact on world growth because it interacts with a host of structural problems that large economies are encountering. The us’s growth potential may have abated from 3 to 2 per cent, while concerns about a ‘fiscal cliff’ at the end of 2012 are exacerbated by the apparently insuperable stalemate in Congress. India is saddled by persistent disequilibria in its public finances, current account and inflation. Brazil’s rate of productive investment has persistently been too low to support a steady 5 per cent growth, because the cost of capital has been too high for too long. China is managing the difficult transition from export-led, accumulation-driven development to sustainable growth.

Emerging-market economies are hampered by reduced trade to Western countries and capital outflows. An econometric model developed at the cepii to study macro-interdependencies allows us to simulate the consequences of a 2 per cent trough in Eurozone gdp from the former 2012 consensus forecast, depending on how the us weathers it. The prc will lose 1 per cent of growth in the first instance and 1.4 per cent in the second. Excluding China, emerging Asia will lose 2.1 per cent and 3 per cent, falling to a standstill if the us does not hold, while Latin America is profoundly affected by the us, a fall of either 0.8 or 2.4 per cent. After two years, these economies would recover either partially or fully, depending on us behaviour but also on Chinese resiliency. Indeed trade and financial linkages between the prc and other emerging-market economies are strong enough to diffuse the effects of the Chinese leadership’s capacity to undertake countercyclical policies at short notice. The other important variable in the world adjustment process is the price of primary commodities, the fall of which would be adverse to Latin America in the short run, but would help increase real income and domestic demand in China, thus reviving imports that would benefit primary-commodity exporters.footnote3

Berlin’s role

Responsibility for the course the Eurozone has taken lies principally in Berlin. Germany is the dominant country within the zone, both because of its economic size and because of the founding compromise of 1991, which modelled the euro on German monetary doctrine. As we have seen, the polarization of competitiveness in Europe has taken place on both sides, like the blades of an opening pair of scissors, not just one. Determined to regain the competitiveness Germany had lost during the 1990s, the country’s authorities and firms imposed a fierce repression of wage costs during the early 2000s which was anything but cooperative; at the same time, the explosion of credit unleashed an expansion of demand far beyond some of the weaker countries’ production capacities. From the start of the crisis, however, Germany has insisted upon an asymmetrical diagnosis, shifting the entire burden of adjustments onto the deficit countries.

This approach long pre-dates the European monetary union. After the end of the Bretton Woods system, German leaders opposed the attempts to re-establish the international monetary system made by the Committee of Twenty, which would have entailed symmetrical adjustments by surplus and deficit countries. When the European Monetary System was devised in 1979, Germany imposed a system of asymmetrical adjustments by other currencies, rather than a symmetrical one based on the ecu. In the early 2000s, when vast disequilibria emerged in the global balance of payments, it was China’s surpluses and not Germany’s that were held responsible, even though the German surpluses were higher than the prc’s as a percentage of gdp. Of course, China’s were constituted principally at the us’s expense, while two-thirds of Germany’s trade surplus comes at the expense of its Eurozone partners.

The Berlin leadership has developed a moralistic interpretation of the crisis. They concede that the Eurozone is important, but insist that it cannot be maintained at any price. The countries whose ‘irresponsibility’ has led the Eurozone to its present state must be made to pay. Hence the exhortations to governments in deficit countries to undertake ‘reforms’ and follow the German path, never mind how unfeasible this is. If the whole Eurozone were to become one big Germany, as Berlin’s discourse suggests, its trade surplus would have to be gigantic in order to sustain its growth, and it would take an enormous expansion of global demand to soak up European merchandise. Alternatively, a euro confined to Germany’s zone of influence—Austria, the Netherlands, Finland—would appreciate by at least 30 per cent, wiping out the German surplus. The country would then be confronted with the internal economic problems that its external surpluses had allowed it to keep latent: lifeless consumption demand, catastrophic demographic trends and high external debt—even if the expedient of hiding the stimulus and bank rescue plan of 2008 in a special account meant it could continue to give the impression of budgetary virtue.

The German approach is grounded in the national tradition of ordo-liberalism, placing great emphasis on rules and regulation. It is a mistake to consider this a version of Anglo-Saxon neo-liberalism; Germany’s rulers distrust the markets, and believe they should be kept under close supervision by strict regulation. As far as the banking sector is concerned, this approach is clearly relevant, as the crisis has shown. The rule-based German banking model worked remarkably well until the crisis of 2002–03, when distressed banks were forced to sell assets which were bought by Anglo-Saxon hedge funds, while the European Commission began to press for the removal of the guarantees the Länder provided to the Landesbanken. The German banking sector then rushed into risky operations in the us, Spain and elsewhere in order to maintain its profits. German banks proved particularly keen on toxic assets overseas. Yet at the same time, the regional banks remained an integral part of the fabric of small and medium-sized businesses that forms the basis of German prosperity.

The Merkel government is thus caught between its desire to put finance in order, by making the banks pay for the excesses they were a party to, and the need to avoid weakening its own banks. After 2008, it decided it would rather freeze the situation than create ‘bad banks’—public financial entities which would take toxic assets and turn them into securities with very long maturities, in order gradually to absorb losses. It therefore suspended ‘fair value’ rules (valuing assets at market price, or prices that simulate the workings of a market), to enable its banks to absorb over time the hidden losses that should have resurfaced in their balance sheets. The case of Commerzbank, the country’s second-largest bank, is emblematic. The same is true of the Landesbanken, which should have been consolidated long ago. All these banks are loaded with toxic assets deriving from the American subprime mortgage crisis. Commerzbank has already received an injection of €18 billion of public money in 2008—the federal government holds a quarter of the capital—without, however, being obliged to clean up its balance sheet. Bad financial governance is facilitated by the incredible laxity of the German authorities, which hardly squares with the moralism of their official pronouncements.

Merkel has repeatedly stated that the banks must be made to pay, but Germany’s actions have been more ambivalent. The stress test carried out by the ecb in December 2011 revealed a critical lack of capitalization in the French and German banking sectors, as well as Greece, Spain and Italy. In order to attain the required levels of capital by 30 June 2012, the banks will try to sell all the assets they can, thus bringing the financial markets down further; and they will continue to limit the issuance of new loans. The Eurozone recession of 2012 may therefore be deeper than anticipated, exacerbating the downward trend. In all this, the power the banks exert over the governments is a major factor. Eurozone governments, and Berlin in particular, refuse to acknowledge that a hypertrophied financial system will have to be radically transformed before Europe’s economies can return to sustainable growth. Their analysis neglects the systemic dimension of the crisis and has led to a policy of ‘small steps’, in which problems are tackled as and when they arise, reduced to temporary liquidity crises caused by actors who can be punished, while the banks remain virtually untouchable. The efsf in May 2010; the ecb’s piecemeal bond buying; the bailout loans for Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and perhaps soon Spain, conditional on surrendering executive decision-making to Troika officials; replacement of the Greek and Italian governments in November 2011; the so-called Fiscal Compact and ecb three-year loans (ltro) in December 2011; the belated ‘haircut’ for Greek debt-holders in March 2012—from the start, the solutions envisaged have been incremental, homeopathic, and have no effect other than to add more layers of debt to stricken countries, the more ‘assistance’ they are given. Above all, the German stance offers no vision of sustainable growth for Europe.

The Eurozone has arrived at a historic crossroads. A sustainable exit from the crisis will require a decisive shift in its political philosophy. When the Maastricht Treaty was signed, political leaders refused to acknowledge that in creating the euro they were changing the very nature of the European project. They thought they could make do with a currency that was incompletely constituted—that is, external to the sovereignty of the member states, yet lacking any sovereign federal body. The crisis has shattered this illusion. The euro must be constituted as a full currency, which means it must be undergirded by a sovereign power. This will require constructing a democratically legitimated European budgetary union, pooling sovereignty to determine medium-term fiscal policy collectively. The ecb’s mandate should be expanded and a broad eurobond market developed on the basis of the fiscal union, targeted at financing long-term growth. This in turn will mean addressing the underlying afflictions of the Eurozone: on the one hand, a continuous weakening of growth rates over the past four decades; on the other, a polarization between the north, where industrialization has been consolidated, and the increasingly deindustrialized south. Integration in the absence of a Europe-wide development strategy succeeded only in concentrating industrial activity in the regions where it was already strong, while the periphery lost ground. To counter this slide into long-term stagnation will require a development project capable of relaunching innovation across the whole range of economic activities, driven by investment largely anchored at regional and local level, with a strong environmental component. By correcting its own imbalances, the Eurozone will be better equipped to play a role in the ongoing structural transformation of the world economy, in which the preponderance of the West will inevitably diminish.