Isn’t there something obscene about the photography of Walker Evans? For hours at a time, he would sit on the New York subway with his camera hidden beneath a heavy overcoat, taking candid pictures of the passengers who sat opposite him. Their effect is uncanny. One untitled image from 1938 shows a man and woman seated close together; nothing in what we see suggests intimacy or even familiarity between them. His face, turned leftwards, rests in an expression of contemplative disappointment, while hers is fixed on something near the viewer (the camera itself?). She looks as if she’s in the throes of a thought so arresting that, despite wearing gloves, she has brought her hands to her face to bite her nails. Evans’s posed pictures of gaunt pastoralists in his classic study of the Great Depression, Now Let Us Praise Famous Men (1941), have this same air. His subjects do not – self-consciously, at least – indulge in the pornography of performing for the camera. The world onto which it opens is a mystery to them: MoMA might as well be Mars.

If there is a charm in this conceit, it is one that we are no longer naïve enough to appreciate. From the outset, the career of contemporary photographer Carrie Mae Weems has been marked by a productive discomfort with naturalism. Born in Portland in 1953, the daughter of sharecroppers from Tennessee and Mississippi, she studied photography and design at San Francisco City College before moving to New York in the late 1970s. There she spent the early part of her career reflecting on the effects of Southern migration and changing gender roles on black American life. Yet the political climate of the Reagan years made it difficult for Weems, at that time a Marxist and labour organizer, to think cogently about these issues.

The ideology of the Moynihan report – which claimed that a culture of poverty was responsible for the social rift between the black working class and respectable America – compelled Weems to offer an artistic counternarrative. The imperative to produce humanizing portraits of the oppressed hangs heavily over her youthful work. Family Pictures and Stories (1982), which focuses on an all-black cast of figures, is exemplary of this approach. In it we see smiling women in factories, a heterosexual couple embracing, two women linking arms and grinning. Whether or not these photographs succeeded in challenging racist narratives about the African-American working class, they ultimately represent a reactive project, in which art is seen as a kind of community service.

Throughout the decade, the emergence of what the French art historian Jean-Francois Chevrier called the ‘tableau form’ – the transformation of photographs into objects intended to be displayed on walls – inflicted a near-fatal blow to the idea of art photography as documentary. The need to consider multiple spectators made an unreflective approach to image-making seem inadequate. Suddenly, it was hard to look at works like Family Pictures and Stories without feeling like a voyeur. In a 2009 interview with Dawoud Bey, one of Weems’s teachers at the Studio Museum in Harlem, she explained how in the 1980s ‘traditional documentary was called into question’:

it was no longer the form; for my photographs to be credible, I needed to make a direct intervention, extend the form by playing with it, manipulating it, creating representations that appeared to be documents but were in fact staged.

In 1984 Weems enrolled at Berkley after developing an interest in Zora Neale Hurston – a novelist and anthropologist who first came to her attention when a friend pointed out the striking resemblance between them. Hurston’s Mules and Men (1935), an ethnographic collection of black Southern folklore which she produced after travelling around the black belt, had a significant influence on Weems. Both artists were concerned with understanding African-American culture as a distinctly modern phenomenon. Inspired by the folklorist Alan Dundes, who taught her in California, Weems would gradually develop a unique style based on fusing the roles of participant and observer, a hallmark of her work from the 1990s onwards.

The best curatorial decision made by the Barbican’s ‘Reflections For Now’ retrospective, which runs until autumn, is one of omission. The earlier documentary photographs – with knowing titles like ‘Black Man Holding Watermelon’ (1987-88) and ‘Black Woman with Chicken’ (1987) – are nowhere to be seen. Weems has described her celebrated Kitchen Table series as part of this documentary mode, but seeing all twenty-five images gives reason to doubt her interpretation. In fact, the photos seem more like a volta in her career. Their two main figures, Weems and a stranger whom she met just before embarking upon the project and hosted in her home while it took place, tell a relatively simple story – but in a way that engages directly with the spectator.

In the series’ most successful image, we see Weems and another man sitting across from one another playing cards. A bowl of what appear to be peanuts sit centrally in the composition, next to them lie shells discarded near a partially drained glass of whiskey. At the head of the table sits Weems, playing the character she describes as her ‘Muse’, wearing a coy expression. Something, not visible to the man, seems to have caught her attention, which is divided between her opponent and whatever it is that has drawn her away. This is the key move of the Kitchen Table series, the use of the spectator to break open what would otherwise be a naturalistic scene.

On the wall are several posters: we can make out Malcolm X, Gary Winograd’s satirical photo of an interracial couple holding chimpanzees dressed as children, and the album cover of John Coltrane’s Blue Train, on which the Muse’s pose is modelled. Combined with an accompanying text that describes a woman’s frustration at the incompatibility of motherhood and monogamy with the world of ideas, the lasting impression one gets from Kitchen Table is of the central character’s inability to sustain any stable notion of self. In every image there is something reticent, something questioning and uncertain about the Muse. Her glance is directed outwards rather than towards her lover, her untouched meal, the children whose movement is caught by the camera as they gather around the table. A contrast is drawn between these other figures, unreflectively absorbed in their activity, and the Muse who pulls away from immersion in any social role. It is to the camera that she turns, as if to ask, again and again, for a new role to play.

Over a decade and a half later, Weems reprised the character of the Muse in photographs taken outside famous art museums. (‘I use myself because I am available’, she remarked in a Q&A session ahead of the show’s opening.) Initially an outgrowth of Roaming (2006), a series of pictures of the Muse standing before the ruins of classical architecture as well as buildings of Italy’s fascist period, Museums (2006) again embraced the dual perspective of observer and participant. Yet the similarities with the Kitchen Table series merely underscore one of the central problematics of Weems’s work: the difficulty of treating history and culture as objects with which one can set up a real confrontation, rather than as merely abstract concepts.

On the last day of shooting Roaming, Weems was struck by the idea of standing before the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea. She intended this as a form of institutional critique: the aim was to get museums to recognize their political responsibilities given what Weems has described as the ‘demographic shift’ towards a less white populace in the US. To my eye, though, these works have the opposite effect. The scale of the buildings and their aura is the first thing that strikes the viewer; second is the indifference of any passer-by to Weems’s antics. The presence of the Muse has the unintended effect of breaking the association between galleries and the idle hustle-and-bustle – bored children and couples on first dates – that takes place within them. The museumgoers in the images, in contrast with the theatrical performance of the artist, appear earnest and genuinely absorbed. Her attempt to repurpose the critical glance of the Muse in these more expressly political works reveals the impotence of such outbursts against the mute walls of history.

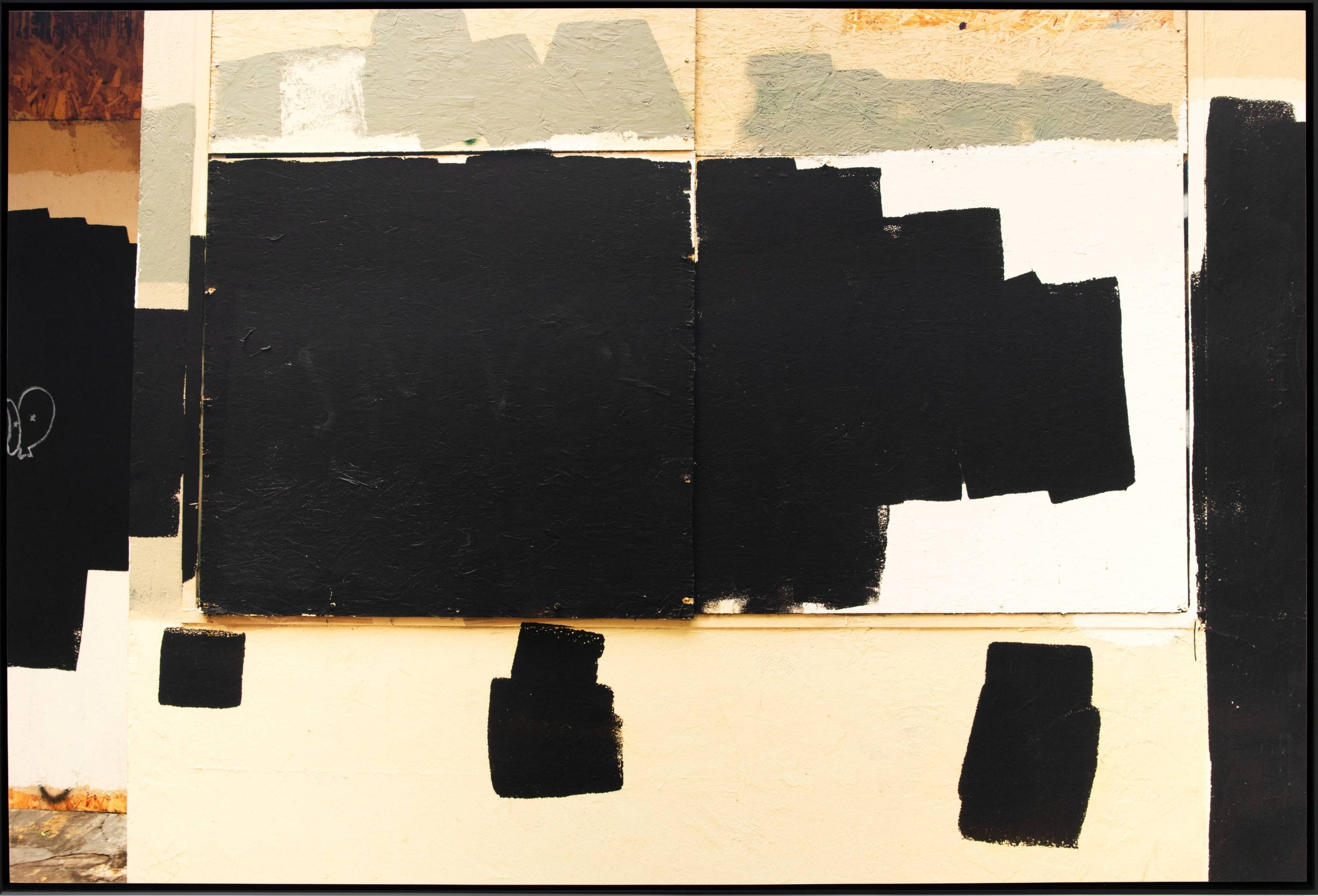

Of the recent works on show at the Barbican, Painting the Town (2021), a triptych of pictures of boarded-up buildings following the George Floyd riots, is the most interesting. Its first image shows several panels of plywood over which a roller of black paint has been applied, presumably with the aim of covering up graffiti. On the left, undeterred vandals have drawn over the black paint: its matt texture makes a better canvas than the rough wood. A quiet dialogue between authority and resistance, whose traces are clear for us to observe, has played out. The second panel appears more abstract; the different shades of black, signs that paint rollers have been applied at different times, convey the passage of time and the movement through it of different people with different, sometimes conflicting, intentions. In the final image, we see the building from its corner, closed not just to the inhabitants of the picture’s world but also to the viewer. From both perspectives, all that can be seen are the external signs of interaction: the plywood that protects storefronts from bricks thrown, the expletives drawn on walls, the hurried efforts to mask these outbursts. Cumulatively, the effect of the triptych is to vindicate an artistic vision that rides roughshod over that of the Kitchen Table and the Museum series. Here, a real confrontation with the world of politics and history can be gleaned, but in the afterglow of interactions with real people, who can only face one another by making themselves unavailable to the spectator.

Read on: Marcus Verhagen, ‘Viewing Velocities’, NLR 125.