Narrative painting in the European tradition tended to depict drama and action: scenes from biblical tales, classical mythology and historical events such as military confrontations and nuptial pagaentries. By contrast, the Chinese tradition of narrative painting was less overtly dramatic and more detached – ‘interstitial’ rather than ‘architectonic’, to borrow terms Andrew Plaks applied to classical Chinese fiction and historiography. Chinese literary narratives put equal, if not more, emphasis on ‘non-events’, or the interstitial spaces between events – purposeless gatherings and inconsequential conversations. Even battle scenes in Chinese historical fiction are often slowed down and their tension diffused using devices such as interspersed verse, discursive digression and frequent recapitulation, producing a ritualised ‘hiatus’ rather than a climactic action. Analagous effects can be seen in traditional Chinese narrative painting, always closely connected to history and literature, and where the ‘interstitial’ quality is if anything more pronounced since paintings convey narrative spatially rather than temporally.

The equivalent of ‘narrative painting’ in Chinese is xu shi hua (picture that tells a story) or gu shi hua (picture of an ancient event).The two concepts are intertwined. Sometimes a contemporary incident was indirectly depicted through the evocation of the past – especially common when the painting served a political purpose. Narrative painting flourished during the political turbulence of the Jin dynasty (1115–1234), when North China was conquered by the Jurchens, ethnically the same group as the Manchu who would seize the whole of China in the seventeenth century, later adding what are today Tibet and Xinjiang to their conquests. The Jurchens defeated the Northern Song, pushing the Han rulers south of the Huai River, re-established as the Southern Song (1127–1279). In the south, the court painter Li Tang produced Duke Wen of Jin Recovering His State, using this ancient story of dynastic revival – from the seventh century BC – to express Emperor Gaozong’s ambition to reclaim the lost land. In the north, Yang Bangji, a Chinese literatus serving at the court of Sinicized Jurchen ruler Hailing (1149–61), depicted the Song’s humiliating tribute mission in A Diplomatic Mission to the Jin, in an effort to legitimize the Jurchens’ rule over North China.

Among the political paintings of the time, the theme of Mingfei chusai (Consort Ming Departing for the Frontier) stands out on account of its female protagonist. Consort Ming refers to Wang Zhaojun (54 BC–19BC), a lady-in-waiting. According to Han Shu (History of the Former Han), she was sent by Emperor Yuan to marry the ruler of the neighbouring Xiongnu empire – an early example of heqin, a diplomatic marriage alliance to ensure peace between China and surrounding states. This historical episode was fictionalised in a collection of short stories, Xijing zaji (Miscellaneous Records of the Western Capital) some three centuries later. There, a corrupt court painter, whom Zhaojun is too proud to bribe, produces a deliberately flawed portrait of the royal consort – so flawed the emperor decides to send her away. Just as she leaves, the emperor appreciates her beauty for the first time, regrets his decision to exile her and has all his painters executed. The legend stirred the imaginations of Chinese literati and street performers alike. Generations of poets commemorated Zhaojun in their verses and made pilgrimages to her hometown. Demoted mandarins compared their own loyalty to Zhaojun’s patriotism, blaming their exiles on deceitful opponents like the villainous painter.

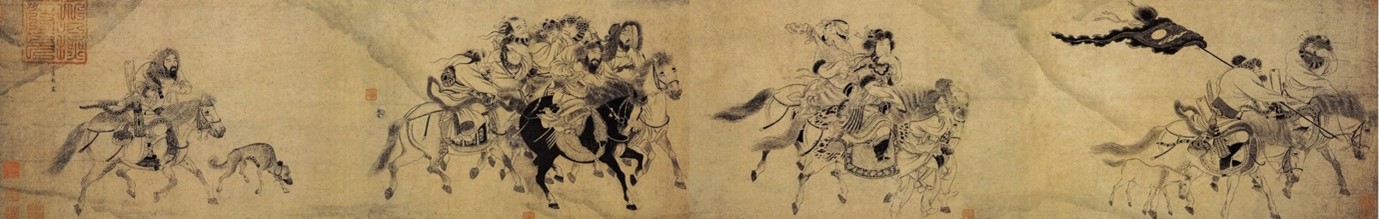

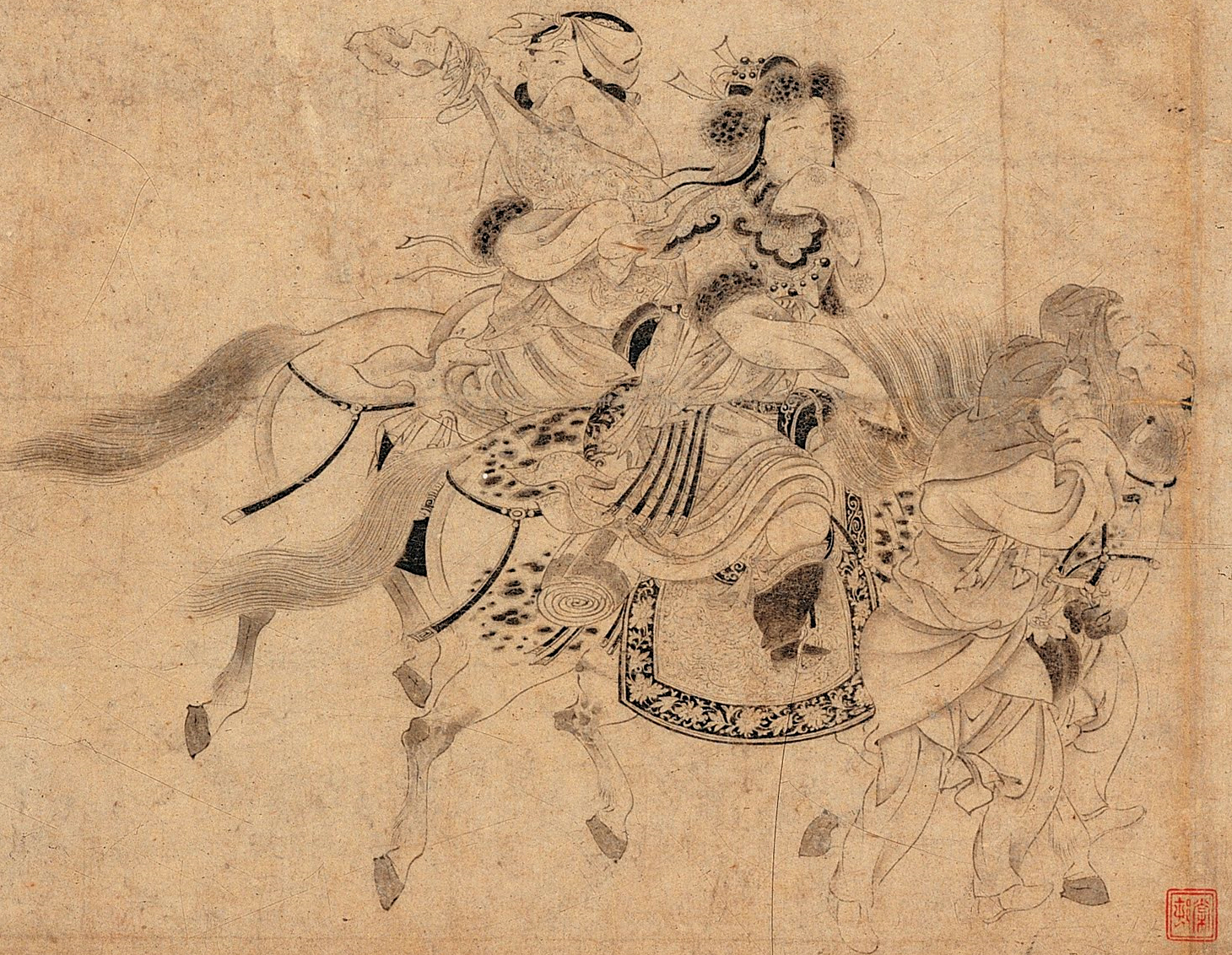

The handscroll Consort Ming Departing for the Frontier is one of the earliest visual representations of the legend. The scroll, which many attribute to the Jin dynasty, is currently preserved in the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts in Japan. It measures 30.2 cm vertically and 160.2 cm horizontally when fully spread out. It shows Zhaojun being escorted into exile. The sand hills in the background are indicated with light-tone washes. Wind is suggested by the fluttering banner, waving ribbons and the sleeves half-covering the faces. The composition comprises four sections, arranged horizontally in a linear fashion. Those who came to look at the painting at the time would have unfolded the scroll from right to left. What they would see first would be the two Xiongnu men on horseback leading the procession, one carrying a flag, with a foal trotting alongside. Next would appear the lady-in-waiting herself and her maid, both riding a horse led by a servant. Wearing a fur hat with earmuffs and dressed like a warrior, Zhaojun grips the reins and looks ahead. The maid turns around as if trying to catch a last glimpse of her disappearing hometown. She carries a pipa, the four-stringed Chinese lute which, according to legend, Zhaojun played well. Following them is a group of seven men, among them a Han envoy holding a fan to shield his face from the wind. The last section depicts a Xiongnu man on horseback holding a falcon, and a hound loping along slightly ahead of the horse and its rider. The scene was painted with ink on paper, in delicate brushstrokes reminiscent of the baimiao style of the Northern Song master Li Gonglin (1049–1106). The narrative is minimal: instead of the drama of the send-off or arrival, the scene presented is, in essence, a ‘non-event’, its figures simply on their way. Yet the circumstantial details of this ‘interstitial’ space trigger the imagination, carrying a train of associations: their daily meals would come from hunting using the falcon, the sorrowful melody emitted out of the pipa would make wild geese linger, the foal trotting ahead of Zhaojun’s horse suggests the motherhood that would inevitably follow her marriage in a foreign land.

Little is known about the identity of the painter, who signed the scroll ‘Zhenyang / Gong Suran hua’ (‘painted by Gong Suran of Zhenyang’. They were once assumed to be a Taoist woman artist because the signature was misread as ‘Zhenyang Gong / Suran’, ‘gong’ meaning temple. The current consensus is that Gong is the surname of the artist, and that Zhenyang was today’s Zhengding county in Hebei province, which fell under the Jurchen rule at the time. The stamp above the painter’s name reads ‘seal of zhao fu shi’, referring to a temporary post in charge of military affairs during wartime. Some speculate that the seal belonged to Wu Xian (?–1234), who was assigned the post in Zhenyang in 1217 and organized military resistance against Mongols, who frequently attacked the Jin state. In 1214, after Genghis Khan besieged Jin’s capital Zhongdu (the southwestern part of present-day Beijing), the Jurchens sent a diplomatic delegation to the Mongols, offering ‘gold and silks, five hundred boys and girls, three thousand horses’, as well as the Jurchen Princess Qiguo, daughter of Emperor Wanyan Yongji, to be married to Genghis Khan. It is possible that Gong’s painting of the legend of Zhaojun was commissioned to record the contemporary heqin event. The hypothesis is consistent with the scroll’s pictorial details: the black flag with a white sun in the middle is the symbol of the Jurchens; the clothes of the Xiongnu riders resemble those worn by the Jurchens and the Mongols; the hair style of two of the envoys was typical among the Mongols. One of the three colophons appended to the painting appears to confirm the theory. The poem ridicules heqin as desperate politics and sympathizes with the painter who, their intention delicately concealed, had succeeded in making the viewer feel sorrow about both the ancient story and contemporary matters.

Was Gong Suran a woman? If so, the painting would be a very rare representation of a woman protagonist by a woman painter concerning a political theme. It would certainly challenge the conventional conception of woman painters in dynastic times as courtesans who depicted willows on fans to reject clients’ advances, or as gentry who picked up their skills from brothers or fathers only to produce paintings as gifts in social exchanges. Museum labels tend to refer to Gong as a woman, but this is an assumption likely based on the name’s feminine intonation. There is no historical evidence available to confirm the painter’s gender or anything else about them. Perhaps the question should instead be: what was the general experience of women under Jurchen rule, especially if we see the image of Zhaojun as not only a historical icon but also a mirror of contemporary lives? Literary sources, such as Jinshi (History of Jin), praise women for their military skills – for leading troops and defending cities. Jin society appeared to be less hierarchical: one Song envoy visiting the Jin state was astonished by the sight of Emperor Aguda’s wife sitting next to him receiving guests and a second wife rolling up her sleeves to serve food. Acculturation went both ways. Elite Jurchen women started to wear silk and read Chinese classics; Han women, meanwhile, had more access to public venues under Jurchen rule than their counterparts in the Southern Song where foot-binding and Confucian ethics would confine them to interior spaces. In a large Jin mural (1167) at Yanshan temple in Shanxi province, women can be seen walking freely on the streets, mingling with men, shopping at the market, playing pipa in an open-air pavilion. This forms a stark contrast to the depiction of women in the Northern Song masterpiece Qingming shanghe tu (Along the River during the Qingming Festival), completed sixty years earlier: of the eight hundred figures featured in the scroll, only a dozen or so are women, many half hidden behind windows or peering from sedan chairs.

The composition of the Gong scroll is almost identical to that of another Jin painting, now stored at the Jilin Museum. It was signed by a court painter named Zhang Yu serving at the Commission of Palace Services. The crucial difference in the Zhang scroll is the omission of the maid figure carrying the pipa. Later generations titled the painting Wenji guihan tu (Lady Wenji Returning to Han). Cai Wenji (177–239), of the Eastern Han dynasty, was abducted by Xiongnu invaders but eventually returned home after twelve years’ captivity. During the Song–Jin period, Wenji’s tale was frequently depicted in paintings, many in sequential scenes based on a verse epic called Hujia shiba pai (Eighteen Songs of a Nomad Flute), composed by the Tang poet Liu Shang (727–805). Like Zhaojun, Wenji also had a contemporary reincarnation. When the Jurchens captured the last two emperors of the Northern Song, they also took captive Empress Dowager Wei, who had to spend sixteen years in Manchuria until her son, by then Emperor Gaozong of the Southern Song, signed a peace treaty with the Jurchens in exchange for her release. Questions remain as to whether the Gong scroll copied the Zhang scroll or whether both were based on an earlier painting. Whichever is the case, there is an undeniable relation between them: a poem on the Gong scroll juxtaposes Zhaojun’s pipa with Wenji’s flute; Emperor Qianlong’s inscription on the Zhang scroll contrasts Wenji’s rehabilitation with Zhaojun’s permanent expulsion. In this alternative tradition of visualizing human experience, the drama of departure or return is out of frame. Instead, a hiatus: an interstitial space that seems directionless and endless.

Read on: J. X. Zhang, ‘The Roar of the Elephant’, NLR 131.