Philip Guston didn’t sleep well. The first room in Tate Modern’s current retrospective is hung with two late images of insomnia: a painting, Legend (1977) and a print, Painter (1980). They show different stages of the same sickness. Legend has the painter in bed, eyes squeezed shut, surrounded by half-formed clapped-out thoughts. Painter shows him at work, all hope of sleep abandoned, eyes gummed near-shut, face pushed as close to his canvas as it will go. The pairing is inspired. It gives clues to the meaning of figuration in Guston’s paintings – to his entire epistemology.

Legend is a large painting, almost two metres across. It shows that unique feeling for colour, or rather for a particular range of colour – roughly, between salmon pink and cadmium red – that Guston tested throughout his career. The painter’s face is a study in this range, from the delicate pinks of his crumpled forehead, flaccid and puffy like uncooked sausages, to the glistening reds of his temples. Pink suffuses the atmosphere and tints each object: the boot heel, the tin can, the billy-club raised by a disembodied fist. Guston’s pillow is crimped like a thought-bubble in a comic strip, and clearly we are meant to read at least some of the objects surrounding him as thoughts, projections of his sleepless brain. They float in pink space. Some cast no shadows.

There are objects here, like the tin can, the horseshoe, and the studded shield, that he returned to again and again, that he simply could not stop painting. Obviously he thought they were significant. But the weight of that significance, its clarity and legibility – these are what the painting puts in question. Take the horse’s rear end, poking out from behind the artist’s pillow. This has been linked to one of Guston’s favourite books, Isaac Babel’s Red Cavalry (1926), a collection of stories based on the author’s time as a journalist in the Polish-Soviet War. But it is an evasive reference, if indeed it is one. Much more important, within the space of the painting, is the way the downward curve of the horse’s tail is repeated and continued by the stream of brown fluid that pours from the lidless tin can onto an odd studded object (a boot heel?). This does cast a shadow, as do the discarded objects that surround it on the studio floor: an old bottle, brilliant green against the pink atmosphere, glass shards, and useless bits of misshapen wood.

Horse’s rear and boot heel; billy club and broken glass: such detritus is the material of Guston’s painting, as it is the stuff of his insomniac thoughts. For all the talk of his political convictions – which were real, and deeply felt, and drove him back to representational painting from abstraction in the teeth of savage criticism – his great paintings dwell among the sweepings of the studio floor, far from the legible images of waking political discourse. They speak a language of uselessness, anxiety, and helpless alienation. Like all insomniacs, the sleepless painter in Legend is tormented by yesterday’s leftovers: the pointless and circular, the looping thoughts that lead nowhere. These are the building blocks of Guston’s art, as they were for so many other modernists. They are what is left to a painter compelled to ‘bear witness’ (a favourite phrase of his) without much hope of averting the horrors he sees. ‘A mound of refuse or the sweepings of a street’, as W.B. Yeats put it, ‘Old kettles, old bottles, and a broken can, / Old iron, old bones, old rags . . . the foul rag and bone shop of the heart’.

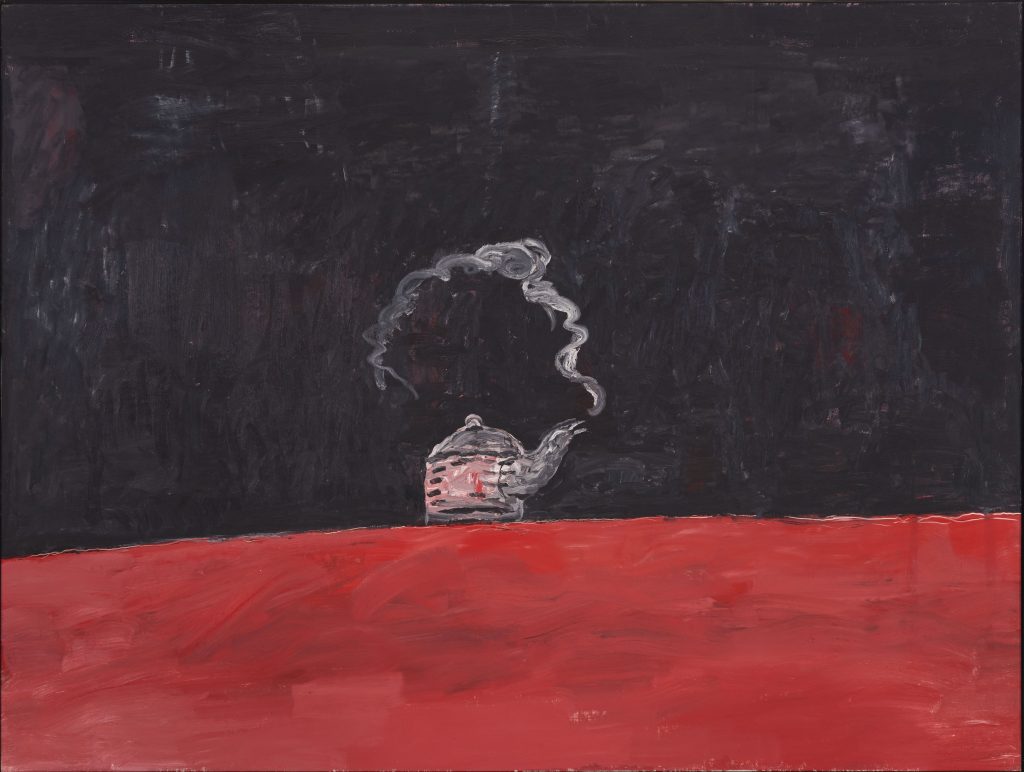

There are many old bottles and broken cans in this exhibition, bones and iron too. There is an apocalyptic Kettle (1978) in the final room. It squats high on a red horizon against a black sky, at once a vision from a nightmare and the very picture of mundanity. This is the promise of Guston’s art: that in paying attention to the broken-down and meaningless – to what is cliché, outworn, comically decrepit – the painter might break through to some new intensity of expression.

Turn again to Painter. The artist, squinting, encrusted with plasters, is shown so close to his work that he has even dispensed with his brush. The two raised fingers he presses to the canvas make the familiar sign of Christ’s benediction. This is a fantasy of painting as creation (rather than production), of the artist as a god, literally in touch with his canvas, rising from his insomniac visions to create new meanings. But it is also self-conscious, doubly mediated, done in a different medium – lithography – with no canvas present. Much of the pleasure in viewing the work comes from the blurring Guston achieves between print and painting, mediacy and immediacy. Surely few artists since Rembrandt have wrought such painterly effects from a print. Look at the flowing, incised greys on the artist’s shirtsleeve, the thick black smudges on his collar, the pooling shadow beneath his canvas. Painter shows Guston, in the year of his death, working at a furious peak. It is a self-portrait as a bandage-swaddled, mummified wreck, but at the same time a master creator, something divine.

Guston was born in 1913, to immigrant Jewish parents, and grew up in Los Angeles, before moving to New York and changing his name in 1936. He showed an early inclination for politics. In 1930 he made Painting for Conspirators, an image of the Ku Klux Klan lynching a Black man with a crucified Christ in the background (present at the Tate only as a small reproduction). He was still signing his paintings ‘Philip Goldstein’ when he made Female Nude with Easel (1935). It is young man’s work, arrogant, mock-heroic, straining for classicism. But it also shows the emergence of certain enduring concerns: the hard cast shadows of dream, the creaking assemblages of objects (boards, nails, staples), the intense reflection on the function and meaning of the painter’s art, and – perhaps above all – that emphasis on the expansive qualities of the colour pink. At this stage it is crisp, delineated: quattrocento pink, wrapping the easel and the painter’s stool in the colours of Della Francesca and Veneziano. The nude, modelled with a solidity drawn from Picasso’s work of the 1920s, is greyscale. She awaits the touch of the artist to give her colour.

Like other American modernists (his school friend Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Willem de Kooning among others), Guston found work in the 1930s painting murals. By 1943 he had worked on fifteen of them, mostly for the Works Progress Administration (a New Deal agency set up to fund public works). In 1934 he and two other artists, Reuben Kadish and Jules Langsner, were commissioned to paint The Struggle Against Terrorism, a mural in the Universidad de San Nicolás in Morelia, Mexico. A vast synthesis of Diego Rivera, Surrealism and the kind of large-format fresco painting perfected by Piero at Arezzo, it is one of the highlights of the exhibition, displayed through a series of ingenious projections. The mural shows the victims of fascist torture. Their massive bodies hang from ropes or are dumped, Christ-like, in open tombs. But the mood is not all sombre. At top right, sickle-brandishing communists charge into the frame, hurling down klansmen and swastikas. Bombast and dynamism are the painters’ creeds here, the searing critique of fascist violence married to a polemical faith in left-wing triumph.

In Bombardment (1937), which hangs nearby, these forces reach crescendo. Painted, like Picasso’s great masterpiece, in response to the bombing of Guernica, it adopts the format of a Renaissance tondo. Guston drives this into centrifugal motion, setting the blast at the painting’s centre back from the figures who surge forwards in extreme foreshortening. It is a painting that strains against its own physical constraints: against painting’s flatness, its stillness, its muteness. At the same time, Bombardment mobilizes these constraints for emotional effect. Its figures are eternally caught in the blast, both thrown and held; sucked in and pushed out. The leg of the naked, screaming child endlessly disappears into the void of the explosion.

Where did this model of engaged art go? How do we get from the young leftist painting communist murals to the tattered insomniac dreaming of horse shit and empty liquor bottles? A broad answer would take in the crushing of American communism, the end of the New Deal, the Nazi-Soviet pact, the waning of the Mexican revolution, World War Two. Mural commissions dried up. Artistic certainties came under pressure. One feels the 1940s for Guston were a period of gradual disintegration. He went on painting his Renaissance-modernist hybrids. But the convictions seem to have ebbed away as the war ground on and the first images began arriving from the death camps. There are no distinct sides in his paintings of this decade; no battle between good and evil. Self-Portrait (1944) shows him hollow-eyed and gaunt, raising a ghostly hand to touch his cheek, as if doubting the capacity of vision to confirm his existence. Gladiators (1940) updates Leonardo’s Battle of Anghiari into a duel of dunces with saucepans for helmets. It is an image of senseless violence unified by the tightness of its composition and the balance of its colours. The pink of its central figure’s strange garment (a dress? a tunic?) echoes in the hoods and fists of his adversaries.

In 1945 Guston brought this sense of uncertainty to an astonishing pitch with If This Be Not I, one of several images of street children that hang in room 3. The setting is some New York slum, piled with trash. Night is coming on. The clock on a distant roof looks past ten, though it might be earlier – the clock might have stopped – there is still a faint blue light in the sky. All is blue here, the hard blue of a winter evening, of street light on frozen metal, and of the stripes on the inmate’s uniform worn by the child at bottom left. He lies, stiff like a dead man, lips drawn back from his teeth. The imagery of the Holocaust is unmistakeable. The painting is haunting, perhaps nowhere more so than in its central figure, another child who stares out from beneath a magnificent paper dunce’s hat (done with a few thick dabs of brown, blue and white). His commedia dell’arte mask has slipped. His gaze is adult, as cold as the air.

It is a wonderful painting but it is also strained, lugubrious, cynical to the point of being hectoring. Guston wrote at the time of the need to find ways to ‘allegorize’ the Holocaust and as the forties wore on he abandoned the directness of his earlier work. Abstraction beckoned, although it was not an easy transition. A work like White Painting I (1951) registers the losses involved – of style and subject matter and commitment – as a kind of bleaching and thinning of the painted surface. The palette is stripped back to the greys and browns of analytical cubism. The central forms hover and crackle against their white ground. Everything seems on the verge of coming apart. Guston made it in a single session. It is easy to imagine him wondering whether he had anything else left to put in.

Guston was able to tolerate these gaps and absences, these crises of indecision. He seems to have driven himself towards them, sometimes destroying whole sequences of his paintings, at other times stopping painting altogether for months, even years, at a time. The effort it cost him to assemble an abstract manner is palpable. Dial (1956) bunches colour and form towards the centre. Reds and pinks stand off the surface in thick ridges. The contrast they create with the green forms is so strong it is almost crass. Thumb marks are visible. Meanwhile, towards the edges, the paint thins, the colours grow less harsh: mauve, sky-blue, here and there a hint of grey. Such abstractions are successful because they find ways to accommodate some of Guston’s old preoccupations – the obsession with certain colours, with the way a particular colour (a blue, a pink) can stabilize and link together a picture of extraordinary violence; the sense of an image straining to allegorize something terrible that is just beyond its reach. They always seem on the verge of materializing into a recognizable form. The meaty densities of Dial almost add up to a figure. There are triangles in Passage (1957-8) that recall the klansmen of the 1930s. In The Return (1956-8) these have become eyes, ears, and noses.

There is a massive teleological bias in writing about these paintings, one I am aware of failing to avoid. Guston returned to figuration with his notorious Marlborough Gallery exhibition in 1970. It is difficult to view his abstractions without these later works in mind, as anything other than steps on a path back to the figure, back to the world. The balances they seem to strike – between the disembodied purity of the painted mark and the tendency of that mark, when set alongside others, to coalesce, to take on something of the look and feel of reality – can seem too provisional. Was Guston really serious about abstraction? Did he ever work hard enough to keep out the world? Such questions are to the point. At their best, Guston’s abstractions show the extreme difficulty involved in separating painting from the outside world, in limning it with a fragile autonomy. Others in his generation – Joan Mitchell most spectacularly – never stopped making paintings out of this contradiction. For Guston this wasn’t an option. The Heads he exhibited at the Jewish Museum in 1966 pushed the line between figurative and abstract to breaking point. They used the contrast between a dark central shape and broad, wet, grey brushwork to bring up, again and again, the image of a human head afloat in a sea of static. They are difficult paintings, depressive. They have something of the stunned tenor of If This Be Not I. The eighteen-month period of lethargy and crisis that followed is hardly surprising. It is what happened next that has always come as a shock.

*

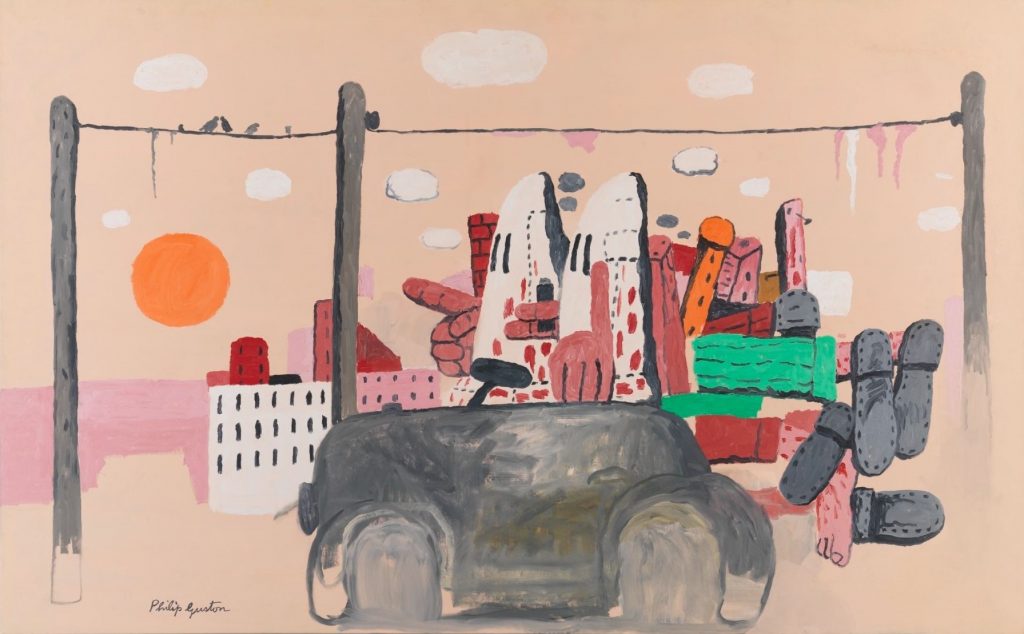

There are continuities between the Marlborough paintings and Guston’s earlier work. But at the time they were read as an absolute break: an attack on modernism, a defection to the other side, or something even stranger. Guston’s friend, the composer Morton Feldman, never spoke to him again after he saw them. Even now, walking into room 8 is an overwhelming experience. The curation is intelligent: you walk through a dark corridor and emerge into a riot of massive, cartoonish forms; exuberant colour; pointed Klan hoods. Everything is pushed to extremes. City Limits (1969) is massive, bigger than any of the abstractions. It shows three klansmen driving a stupid cartoon car through a desolate landscape. The whole surface seems built from those smeared, liquid pinks and reds. Even the Klan hoods are more pink than white. But the affect has changed. There is no hint of the quattrocento in Guston’s pinks here, nothing of balance or grace. The blacks and greys blended with his colours make them look grubby, like greasemarks on cheap newsprint.

These paintings were horrifying in 1970 and still are (witness the show’s near-cancellation back in 2020, on grounds that it might give offence). They pose a chilling equivalence between their elements. Everything – klansmen, buildings, corpses, cars, windows, cigarettes – is rendered in the same cheerily inane cartoon style drawn in part from Guston’s reading of comic strips like Krazy Kat. The tiny paintings on one wall, which Guston lived with, make the point brutally clear. Each shows a personage in his late paintings. The rubbery form of a skyscraper is there in one; a hanging lightbulb in another. A Klan hood appears in the series too, but fungibly, as one element among many. Dawn (1970) shows another carload of klansmen with a tangle of human body parts protruding from the back of their car. Blood drips from one of the feet. The sun in the sky is a jolly orange disk. The birds on the telephone wire might as well be singing.

It is this cartoonishness that people find disturbing. There is a chasm between the moral clarity of Guston’s work of the 1930s, with its bands of communists ever ready to fight off the Klan, and a work like Dawn or The Studio (1969). In the latter, perhaps his most famous image, it is the artist himself who wears the pointed hood, puffing on a cigarette while painting (yet) another klansman by the light of a single bulb. Guston makes the Klan cute. He identifies himself with those he is supposed to despise, and identifies these with the most debased products of American popular culture. The Studio recognizes the enmeshment of racist violence in the very tissue of American life, as much a part of its workings and history as cigarettes, cars and cartoons. More terrifying still, it suggests that there is no position outside this culture for the artist to take up; no separation that would arrive with the force of a moral binary. The horror of the landscape in City Limits, with its blood-red ground and looming skyline, is of a world in which the Klan have lost their identity as an embodiment of evil and become normalized, banal. We are a long way from the ‘us and them’ of World War Two and the Mexican Revolution. ‘We are all hoods’, as Guston put it.

This sense of helpless complicity, with all the paralysis it implies, returns us to the outlook of the insomniac, obsessing over a world he cannot change. Worry, with its circling momentum, disconnected objects and desperate leaps of inference, is often the subject of Guston’s work in the 1970s, his last decade, during which he produced many of his greatest paintings. Painter’s Forms II (1978) shows a mouth and part of a jaw literally vomiting up the objects – the boots, legs, cigarettes and tin cans – that Guston called his ‘visual alphabet’. It is an image of useless compulsion, as bleak and relentless as anything else to come out of this highpoint of the Cold War.

The final room, titled ‘Night Studio’, is the best in the exhibition. It is revelatory: the full range of Guston’s late works dealing with sleep, death and isolation become apparent. Kettle sits on its high red hill. The figure of the artist curls beneath a too-thin blanket, stick limbs shivering against a black void. Hands gesture unintelligibly. Flames gutter out in the dark. By this point the stakes of these images, their conjunctions of meaninglessness and desolation, the stress they place on bearing witness – even when to do so is impossible – are clear. In Couple in Bed (1977) the artist clutches his brushes even as he pushes his face so close to his stroke-stricken wife’s that their features disappear into each other’s. Guston never lost his faith in modernism; he sought the meaning of modern life, its poetry and heroism, among the wreckage. Creation was the other side of destruction. A sleepless night could always produce a painting.

The last work in the show, The Line (1978), shows a godlike hand reaching from a cloud. It makes the same divine gesture as the artist in Painter, although here the two fingers grasp a stick of charcoal and draw a line. It is at once an image of defunct cliché, absurdly anachronistic in the age of burgeoning postmodernism (who on earth still believed in the artist as divine?), and a serious statement of the painter’s vocation. Such paintings resonate today because they are able to hold both poles together: to be both anachronistic and contemporary. Ideas do not disappear simply because they have become outmoded. Like fascism or the Klan, returning to haunt capitalist modernity in ever-new configurations, it is when left behind that they can be most dangerous.

Read on: Saul Nelson, ‘Opposed Realities’, NLR 137.