In Travels with My Aunt, Graham Greene tells the story of a man who decides to travel the world as he believes it will ‘make time move with less rapidity’. After suffering a stroke in Venice at the beginning of his tour, he buys a crumbling Italian villa, where he resumes his journey on a different scale, moving weekly from one bedroom to another. A year later, he dies ‘on his travels’ – dragging his suitcase to the last of his fifty-two rooms. In a similar fashion, the British artist Mike Nelson equates the exploration of interiors with larger travels in time and space. But while Greene’s story is strangely upbeat, Nelson’s installations are grim. Though absorbing and at times witty, their depiction of today’s world is unflinchingly bleak.

Nelson originally made his name with maze-like immersive installations such as The Deliverance and The Patience, which was mounted in a derelict brewery in Venice in 2001 and has now been recreated for an ambitious survey of his work at London’s Hayward Gallery, on view until 7 May. Like his cult piece Coral Reef (2000), it consists of a bewildering network of dingy rooms and twisting corridors. One room, its walls painted lurid shades of blue and purple, contains an old chest that doubles as a multi-faith altar, with various ceremonial objects – animal skulls, a small buddha, pseudo-Egyptian busts – arranged on top of it. There are two cramped bars, one decorated with tacky maritime paraphernalia, the other with old countercultural symbols: an image of Elvis, a picture of a hemp leaf. Elsewhere rumpled sleeping bags lie on a patched-up camp bed. Scraps of fabric cover a work bench in what appears to be a sweatshop. Beyond is a gambling den and a poky travel agency with yellowing posters of passenger planes. The surfaces are worn, some of the walls are bashed in, the furniture is manky. A musty smell pervades the work, the tang of objects collected from skips and car boot sales.

Many of Nelson’s signature motifs are present here, in the electric fans and bare lightbulbs, the old sockets, foreign cigarette packets and mirrors. These and other items suggest neglect and precarity; many point to the difficulties faced by migrants in the UK, whose disorientation is evoked through the overarching motif of the labyrinth, the multiple doors that confront the visitor at every turn. The rooms reek of boredom, off-the-books employment and naked exploitation. Signs of travel dovetail with those of entrapment: the whole installation is windowless.

As ever with Nelson, the title is crucial. It refers to a large group of sailors and contracted settlers who set off from Plymouth in 1609, bound for the Jamestown colony in Virginia. Shipwrecked just off the coast of Bermuda, they decided to stay and set up an autonomous community on the island, but were eventually forced to build the ships – The Deliverance and The Patience – that then took them to Virginia, where a much harsher life awaited. Hence, while the title inverts the axis of migration, Nelson also uses it to hint that in the present, as in the seventeenth century, the hopes of migrants are misaligned with their prospects. The utopian echoes in the names of the two ships, as well as the reference to the Bermudan interlude, acquire an ironic tinge as they run up against the squalor of the rooms.

Nelson’s preoccupation with dispossessed subjects is evident in other early works on display at the Hayward. The Amnesiacs (1996- ), for instance, is a tableau made out of found materials in a chicken-wire cage. It is named after a fictional biker gang of First Gulf War veterans suffering from PTSD and memory loss. The cage, apparently, is their den. A motorbike is fashioned out of a large pot, a wooden trunk, bullhorns and a wool pelt, a snake out of a stick and a plastic bottle. Motorbike helmets are carved to look like skulls. A stool and the top of a plastic vat become a dog; a bike chain stands in for a necklace or whip. The whole scene sits on a bed of newspapers strewn with crab claws and razor shells. In its playfulness, Nelson’s handling of these materials jars with the overtones of violence, confinement and impotence. Implicitly, the biker-veterans are delusional: they can’t tell the difference between bullhorns and handlebars, a stool and a dog. Fantasy here is more demeaning than consolatory.

On the upper level at the Hayward the visitor finds a large installation – conceptually more streamlined but equally desolate. Triple Bluff Canyon (the woodshed), made in 2004, is a replica of the shed that the US artist Robert Smithson buried under tons of earth on the campus of Kent State University in 1970, shortly before four students were killed there by National Guardsmen at a protest against the Vietnam War. Nelson is presumably drawn to Smithson’s Partially Buried Woodshed because it has come to be read in light of the killings. It would seem that for him the original shed, which eventually collapsed under the weight of the soil, conflated natural decay and violence. Burying his own shed in a sand dune rather than a mountain of earth, he presents the work, initially conceived for Modern Art Oxford at the time of the Iraq War, as a monument to the insanity of the US-led invasion. Today, it also reads as a commentary on creeping desertification. The shredded tyres added to this new version – signs of fossil fuel consumption – support both interpretations, recalling a war triggered partly by thirst for Iraqi oil while also providing a vision of environmental disaster.

These projects of the 1990s and early 2000s display an obsessive attention to detail in the design and construction of the immersive spaces and the selection and arrangement of found objects. Take the doors in The Deliverance and The Patience: most are scuffed, their paint flaking, a couple have reinforced glass panels, others have pull handles. Each one is different – and together they conjure poverty, cheap DIY solutions, spaces that are neither properly domestic nor public. Nelson’s art describes hellish places, each keyed to a juncture in the recent past through the accretion of suggestive features.

The bleakness of these environments is relieved by occasional moments of humour. A door leading to another grimy room has ‘Sanitary Department’ etched into its glass window; a map showing ‘Global Natural Perils’ hangs on a wall in the travel agency; ‘Exit’ signs proliferate in a maze. A helmet, a means of protection, does duty as a skull. The works are littered with such darkly comic asides. And the details, as they add up, become proto-narratives. They invite speculation, asking to be read as clues to the identities of the people who work, sleep and drink in these spaces, to their travels and aspirations, their memories and present rituals. These incipient storylines raise uncomfortable questions for Nelson’s audience. What are our roles, our motivations for looking? The works cast us as inquisitive outsiders, using their narrative openings as bait for voyeurs. Hence the cage in The Amnesiacs: it doesn’t just confine the bikers; it also offers them up for our inspection. As the curator Ingrid Swenson observed of The Deliverance and The Patience, ‘you felt really self-conscious, as if you were somewhere you shouldn’t be.’

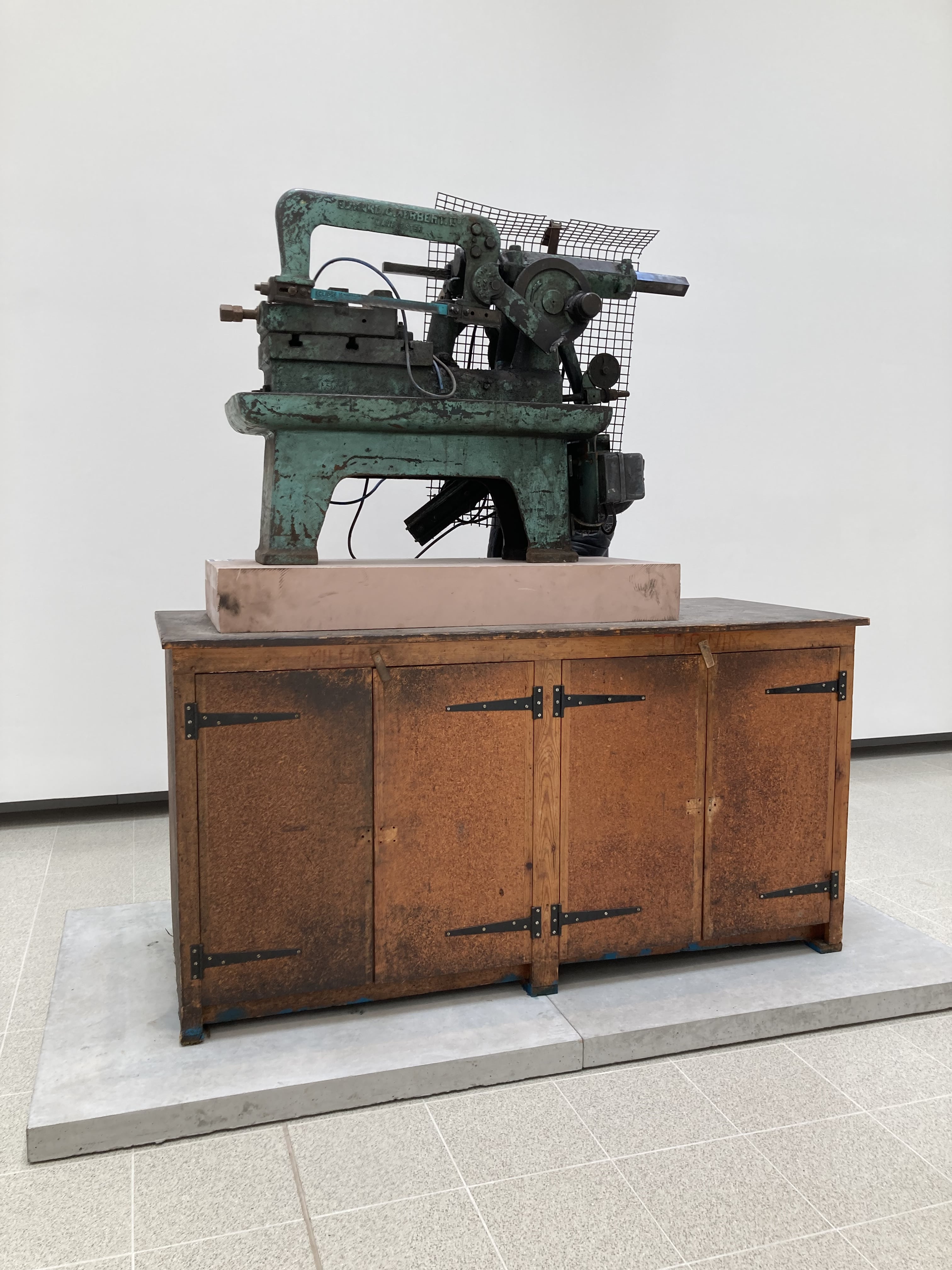

Some of the more recent works on display at the Hayward fare less well, The Asset Strippers (2019) in particular. When this collection of used industrial and agricultural appliances was shown in Tate Britain’s Duveen Galleries before the pandemic, it was starkly impressive. Among the machines were a surface grinder, a mechanical hacksaw, a paint sprayer and hay rake, all shown on makeshift plinths that were themselves made up of industrial implements, including steel trestles and a lorry ramp. As the artist explained in a text written for the Tate and reproduced in the Hayward catalogue, the work looks back to the postwar period, when members of his family worked in textile factories in the East Midlands. The title alludes not just to the decline of manufacturing but also to the rise of the digital economy: Nelson bought the appliances at asset strippers’ online auctions. In the Tate, these hulking machines were at once incongruous and oddly fitting: they brought working-class labour into the museum, showcasing the bluntness and immediacy of that confrontation, yet their imposing stage presence was also a match for the pomp of their surroundings. Nelson pointed out that Duveen had made his fortune selling art objects to wealthy industrialists. In bringing mechanical relics into the museum, the artist was reminding us that industrial labour was already present in those vast galleries. It had paid for them.

At the Hayward, however, this conflictual dialogue between the work and its context is lost. Here, the industrial appliances – a smaller selection – stand in a white cube. The potency of the original piece lay in its site-specificity. In the current show, the machines look massive and intriguing but ultimately tame. Nelson once hoped that his immersive work would ‘obliterate’ the gallery, thus evading capture by the art market and its attendant media circus. Yet he wrote that he became disillusioned after taking over the British pavilion at the 2011 Venice Biennale, and subsequently turned to monumental sculpture. At the Hayward, it is difficult to see how his more recent sculptural pieces inhibit their metabolization by the art world. On the contrary, they seem to have a strong art historical pedigree, as Nelson signals in his text when he likens them to the work of Jacob Epstein and Henry Moore. With The Asset Strippers he revisits the modernist sublime, giving it a nostalgic twist that diminishes the installation’s original abrasiveness.

Even those pieces that lend themselves more readily than The Asset Strippers to recreation in another location are not at their best in the current exhibition, which brings together a number of works by an artist who has in the past shown one project at a time. His pieces don’t line up neatly like paintings on a wall. They tend to annex spaces, the immersive works in particular. To attend to one is to enter a world and briefly accept its parameters – its inhabitants, as identified by their traces, its spatial configuration and situation in time. At the Hayward, the visitor is asked to do that over and over again. One account, that of his career, serves as the master narrative, of which all the stories he tells then become illustrations. For those artists who, like Nelson, ordinarily produce exhibitions rather than discrete works, the survey show is an awkward fit.

In 2022, Nelson made one more immersive work: a tiny room with a camp bed and, all around it, travel guides on book shelves. Titled The Book of Spells (a speculative fiction), it is on display at Matt’s Gallery on Webster Road in South London until 23 April. As claustrophobic as any of the chambers in The Deliverance and The Patience, it again pits travel against the forces that constrain it, which here include the Covid pandemic. In an interview, Nelson intimated that every item in the room is designed to support this overall impression: ‘that’s why I’m desperately looking for an old door closer as the door needs to close behind you – because when you see the outside world, the spell is broken.’ That is partly what happens at the Hayward: the outside world intrudes, in the form of the gallery, its architecture, the curatorial tradition of the survey show. To an extent, the spell is broken.

But it would be wrong to make too much of this. The show remains hugely compelling. For visitors who couldn’t travel to Venice for the first incarnation of The Deliverance and The Patience, or to Oxford for Triple Bluff Canyon, it is an opportunity to see these pivotal works in person. They still captivate viewers and ‘force them to look’, as Nelson wrote of his early work in 2019. Although ‘force’ may not be the right word here; rather, they persuade us – and they do so by striking a kind of bargain. Visitors can enjoy trespassing, clocking details and following leads. They can enjoy the intricacy of the works as story-telling devices, but only if, in the process, they take a clear-eyed look at some of the more toxic effects of our current political conjuncture. The grimness of seeing is the price he exacts for the pleasure of looking.

Read on: Marcus Verhagen, ‘Art in a Narrow Present’, NLR 135.