In 1524, a peasant uprising against grinding poverty and feudal rule swept across parts of what is now Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Though it was eventually crushed, the revolt gave rise to folk legends that endured for centuries, among them the story of a towering woman fighter. ‘Black Anna’, as she was known – likely based on the peasant leader Margaret Renner – is the central figure in the German artist Käthe Kollwitz’s striking graphic cycle, ‘The Peasants’ War’ (1901-1908). Black Anna is depicted rallying her forces, her outstretched arms directing a line of armed men who surge across a field. The prints dramatize a dialectic of oppression and resistance: elsewhere we see the upward swoop of armed men rushing through a castle entryway, a mother bending over her dead son.

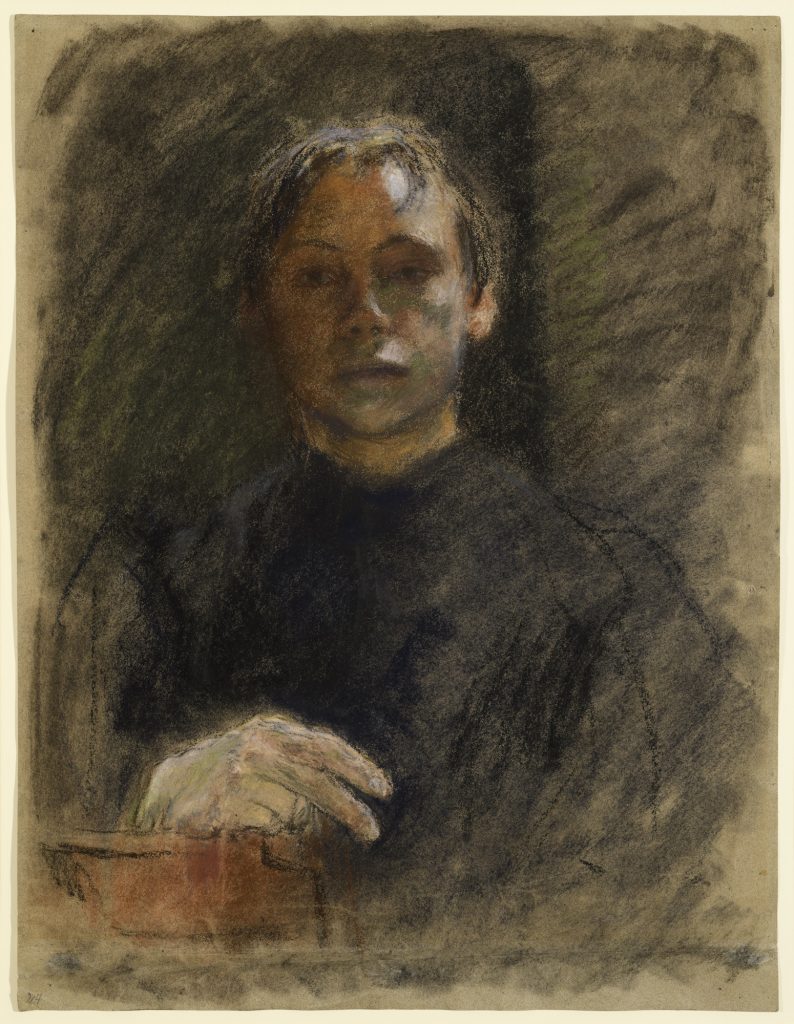

Kollwitz herself was an unusual figure in many respects. A female artist of the early twentieth century who was widely recognized during her lifetime, her primary medium was printing rather than painting. Committed to narrative and representation in a heyday of abstraction, Kollwitz valued sincerity over irony, distancing her from the key artistic movements – Dada, Neue Sachlichkeit – of the period. Never a member of the SPD or KPD, she nonetheless produced socially engaged art centred on the working class. A survey of her work currently showing at the Museum of Modern Art in New York – encompassing early paintings, numerous self-portraits, the major graphic series, the popular posters – brings these idiosyncrasies into relief. It also reveals some of the animating tensions of her oeuvre, among them the use of portraiture as means to represent collectivities, and of an intimate visual language to address world-historic themes.

She was born Käthe Schmidt in Königsberg in 1867, in what was then Prussia, and raised in an educated, upper-middle-class family of socialist and dissident religious convictions. Though neither of Kollwitz’s sisters worked outside the home, her father encouraged her to pursue an artistic career, paying for years of training and travel. Her ambitions were shaped by this paternal support, as well as encounters with socialism and feminism – formative writings included August Bebel’s Women and Socialism and the journalism of Clara Zetkin. In 1891, she married a doctor, Karl Kollwitz, and the couple settled in the working-class district of Prenzlauer Berg in Berlin.

The marriage disappointed her father, who thought settling down spelled the end of her artistic ambitions (‘You have made your choice now. You will scarcely be able to do both things.’) Yet the couple divided their apartment between his practice and her studio, and the daily life of the clinic had a galvanizing effect on Kollwitz’s art: ‘When I became acquainted, especially through my husband, with the severity and tragedy of the depths of proletarian life, when I met women who came to my husband, and also to me, looking for help, the fate of the proletariat and all its consequences gripped me with all its force.’ Yet Kollwitz admitted that she was initially drawn to ‘the depiction of proletarian life’ for aesthetic rather than social reasons. ‘The real motive’, she wrote, ‘was because the motifs chosen from this sphere gave me, simply and unconditionally, what I found beautiful.’

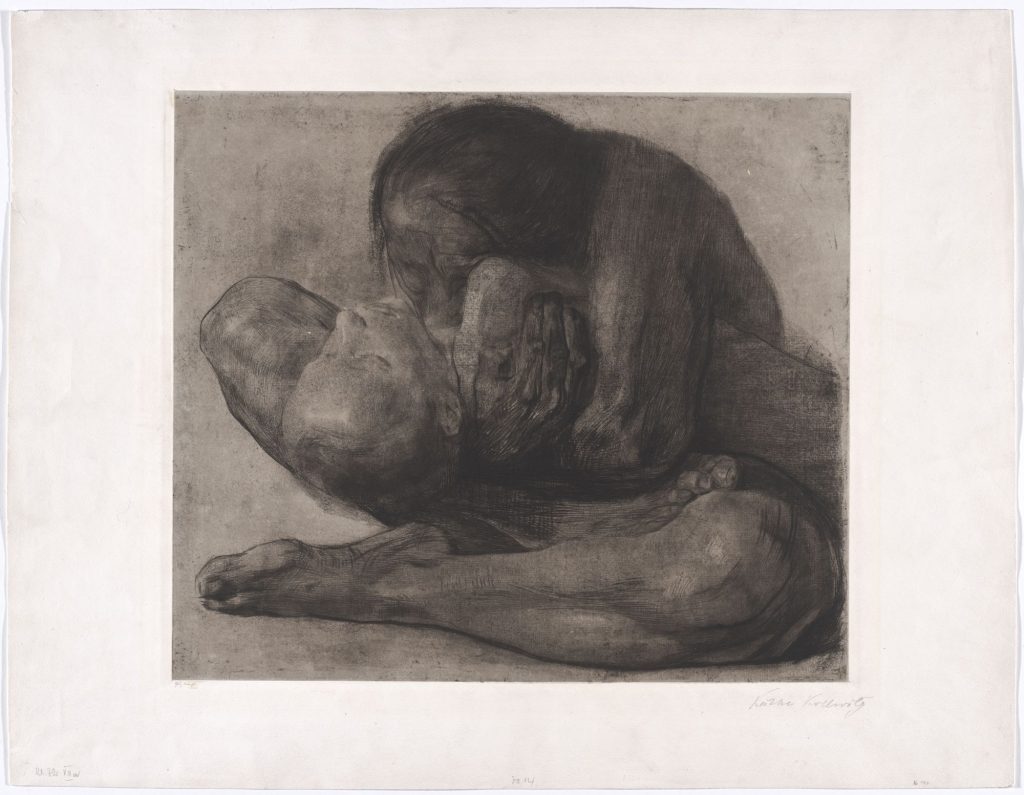

Her first major undertaking was historical. In 1893, she saw Gerhardt Hauptmann’s play The Weavers, which dramatized the struggle of these early economic casualties of the industrial revolution. This inspired ‘A Weaver’s Revolt’ (1893-1897), three lithographs and three etchings, which took over five years to produce and established Kollwitz’s reputation. She was not the only visual artist of her day to take up the subject – Max Lieberman’s The Weaver (1883) also portrayed loom-weavers at work. In Kollwitz’s rendering, however, work has stuttered to a halt. A malnourished child lies on a bed, and there is a sense that the family cannot work their way out of a desperate situation. This sets the series in motion: the workers rebel against their conditions, but the revolt is defeated, and we conclude with the return of the victims’ corpses.

Kollwitz was a slow and methodical draughtswoman, and MoMA’s presentation displays her process of revision, with preparatory sketches arranged alongside the finished works. These reveal her emerging vocabulary: in an early version, for instance, a weaver’s hand hangs open; in the final work, their hands are clenched, a detail that transforms the scene. Yet its emotion is nonetheless ambiguous. Are the women surveying the bodies of their husbands and sons paralysed with grief or simmering with rage? The series was shown in the Great Berlin Art Exhibition, where it was denied a gold medal by the state minister of culture who found it, in MoMA curator Starr Figura’s words, lacking in ‘mitigating or conciliatory elements’ and thus ineligible for ‘explicit recognition by the state’.

This printmaking drew on a variety of modes and references, from the caprichos of Goya and the virtuosic engravings of Dürer to the radical woodcuts and satirical graphics of magazines like The New Masses and Simplicissimus. Kollwitz’s fine marks and muted tones foster a close connection with the viewer, the complexity of each print obliging one to lean in. This is part of their persuasiveness; they demand physical proximity to their scenes of anguish. ‘The passion inspired in her by her theme’, a disapproving Clement Greenberg wrote in 1945, ‘required a complementary passion for her medium, to counteract a certain inevitable excess.’

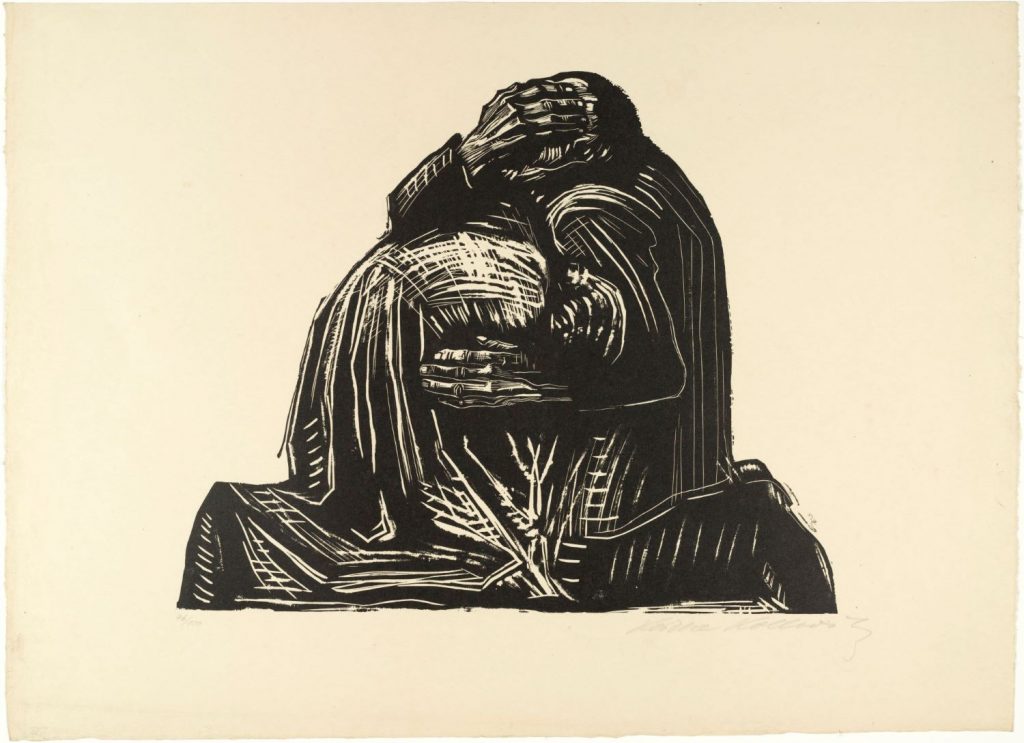

Lithographs and etchings predominate in these years, but by the First World War Kollwitz was increasingly turning to the starkness of woodcuts. In some, the background is left entirely uncut; figures emerge from a solid black void. Notable among these is her 1920 woodcut of SPD leader Karl Liebknecht’s funeral. The picture feels poised at the moment mourning tipped into defiance, as the wake erupted into mass demonstration. Though Kollwitz was asked by his family to produce the image, some wondered whether it was appropriate that the portrait be done by a non-party member. Kollwitz felt that she could portray the murdered Spartacist leader without ‘following politically’; that as an artist she had ‘the right to extract the emotional content out of everything, to let things work on me and then give them outward form’.

Artistic detachment is not easy to detect in Kollwitz’s work, particular after the tragedy of losing her younger son, killed at the First Battle of Ypres in 1914. Peter, who had left school to become a painter, was a minor when the war broke out and needed permission from his parents to enlist, which Kollwitz gave despite her husband’s reluctance. Kollwitz’s guilt was overwhelming, and she struggled to work: ‘I am seeking him as if I had to find him in the work’, but ‘I might make a hundred drawings and not get any closer to him’. It took years to complete the woodcuts that made up ‘War’ (1918-1922). The series went through three editions, with hundreds of copies in circulation; upon completion Kollwitz wrote that ‘these prints should be sent all over the world and give everybody the essence of what it was like – this is what we all went through during these unspeakably hard times.’

Her focus was not the battlefield, but the survivors and their loss. The Sacrifice and The Volunteers, which open the series, depict a mother holding her child out to an enveloping blackness and an arc of faces blending into skulls. The compositions echo recruitment posters, substituting boosterism for grief. Motherhood is both an illuminating and constraining lens through which to view Kollwitz’s work. Notwithstanding her father’s conviction that she had sacrificed her art to family, the MoMA audio guide, which features commentary from the novelist Sheila Heti (perhaps best known for writing about her decision not to have children), suggests that, absent maternal feeling, she may never have produced some of her most significant works.

Kollwitz was also a sculptor and spent years on a monument to Peter. An early sketch shows a mother and father kneeling before their son’s body, but the final version of Grieving Parents (1914-32) subtracted his remains, leaving the parents – who resemble Kollwitz and her husband – with an empty space between them. The sculpture was displayed at the Vladslo Cemetery in Belgium, where more than 25,000 German soldiers are buried. Kollwitz’s sculpture was clearly influenced by Rodin, whom she had met in Paris, and whose preference for naturalism over allegory and textural depth over polished, idealized lines concurred with her own tendencies.

The exhibition includes several other sculptures, including Pair of Lovers (1913-1915), an early effort that shows an entwined couple, one seated in the lap of the other. The face of the larger figure is hidden, buried in the neck of their companion. The ambiguity of the scene meant that the sculpture was miscatalogued for a time as Woman with a Dead Child. In Kollwitz’s work, both romantic and parental love are figured as physical melding. In Mother with Two Children (1932-6) a seated woman folds her arms and legs around two babies. The proportions of the bodies are distorted – necks shrunken, hands enlarged, torsos shortened – so that the trio blend together. In Farewell (1940), not shown in the exhibition, a mother grips her child so tightly she appears to disappear into him. The women’s motive in these latter two are agonisingly clear: to shield their children from carnage.

In the interwar period, Kollwitz contributed to anti-fascist campaigns and the Communist-led Workers International Relief. Her famous Never Again War poster (1924) – designed for the Central German Convention of Young Socialist workers – was distributed internationally. With the rise of National Socialism, her husband temporarily lost his medical licence and she was forced to resign from the Prussian Academy. Kollwitz found herself barred from public art programmes, her work removed from exhibitions. Karl died in 1940 and in 1943 Kollwitz accepted an aristocratic patron’s offer to take refuge in Moritzburg (shortly afterward her apartment of fifty years was destroyed in an air raid). She died in April 1945, days before the first Red Army tanks rolled into Berlin.

In Kollwitz’s last major cycle of lithographs, Death (1934-37), Death is depicted almost as a friend; in one image, it is figured as an inviting lap, cocooning a dying adolescent like an easy chair. Death is something to which ‘a woman entrusts herself’, as the title of one print has it; though elsewhere it is represented as a black-cloaked predator who seizes children from their mothers. It separates, welcomes, liberates, with pitiless certainty. And yet, Kollwitz’s final lithograph, Seed Crops Should not be Milled (1941) – the title was taken from Goethe – in which a woman wraps her arms around her children strikes a note of enduring resistance. In 1944, she wrote that ‘every war is answered by a new war’ unless ‘everything is smashed’, and ‘that is why I am so wholeheartedly for a radical end to this madness, and why my only hope is in a world socialism’. ‘Pacifism’, she concluded, ‘is not a matter of calm looking on; it is work, hard work.’

Read on: John Willet, ‘Art and Revolution’, NLR 112.