Lynette Yiadom-Boakye is a London-born portrait painter whose work would have been showing at the Tate Britain until late May were it not for the second lockdown. The daughter of Ghanaian immigrants, Yiadom-Boakye studied at Falmouth College of Art and the Royal Academy, gaining her postgraduate degree in 2003, before being offered a major solo exhibition by the Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor. After a number of successful follow-up shows and a job offer from the Ruskin School of Art (where she continues to teach on the Master’s programme), she became the first black woman to win the Carnegie Prize in 2018. Her portraits typically depict fictional black figures in settings whose geographical and historical locations are unclear. This ambiguity, combined with the racial profile of her characters, has informed much of the discussion of her work.

A remarkable feature of Yiadom-Boakye’s oeuvre is the range of dispositions and moods that she portrays. Ranging from conviviality, intensity bordering on aggression, contemplative ease and performative eroticism, her figures seem to inhabit a socio-cultural universe that is complex and mysterious. In this world, men and women sit with wild animals at their feet and in their arms (foxes and birds most commonly), and appear entirely absorbed in activities which the viewer can never fully grasp. Her figures live in a space of pure sensuality which is difficult to nail down, as if their raw expressivity outruns the physical forms which seek to contain it.

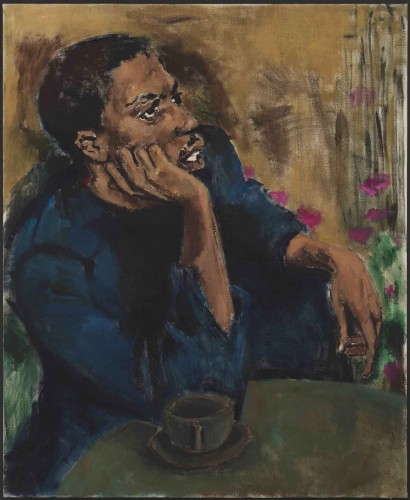

Photographic reproductions of Yiadom-Boakye’s work do not do justice to its painterly quality. Her backgrounds, rich with depth and colour, are as much a subject as the figures that appear within them, though this is hard to gauge without the physical presence of the canvas. Yiadom-Boakye often uses the dark blues and browns of her backgrounds to camouflage her subjects – a technique that, according to the artist, involves ‘a continuous preoccupation to achieve the right balance between the skin of the figure and the surroundings.’ For the viewer, the effect of this balancing act in which ‘all marks are there to support the figure’ is that of being pulled towards the image by a subject who constantly withdraws. This is carried through dramatically in ‘Fourth Magic’ (2008), where the body of a seated central figure is suggested by the contours of black clothes, out of which his hands and head emerge. The depth of colour in the background resembles something from Rothko’s Seagram paintings. But whereas the American artist filled his spaces with seemingly pulsating rectangular shapes, Yiadom-Boakye occupies hers with a subject who seems to bleed into his surroundings. A flash of light illuminates the figure from above, revealing a handsome dark-skinned man who looks over his shoulder at the viewer, in a gesture that evokes Manet’s ‘Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe’.

The influence of Manet appears again in ‘Bound Over To Keep The Faith’ (2012), where one of Yiadom-Boakye’s recurring characters mimics the famous nude’s pose. Here, as in ‘Fourth Magic’, Yiadom-Boakye implicates the viewer in the image. Diderot famously thought there was something vulgar about this kind of performative self-awareness, writing of ‘Susanna and the Elders’ that

The canvas encloses all the space, and there is no one beyond it. When Susanna exposes her naked body to my eyes, protecting herself against the elders’ gaze with all the veils that enveloped her, Susanna is chaste and so is the painter. Neither the one nor the other knew I was there.

For Diderot, preserving the purity of the image was only possible if one fought against the temptation of self-referentiality. Yiadom-Boakye, by contrast, is more equivocal about the role of the beholder.

Her subjects are entirely imaginary, giving them an idealized quality which is lacking in figures studied from life. Certain characters reappear throughout her work, maintaining the same clothes whilst shifting pose, or the same pose whilst changing clothes. This fictiveness allows her to riff on a central conceit of literature: the construction of a world that exists only for the reader. At times, Yiadom-Boakye manipulates this conceit to challenge or confront the viewer – using the intimacy between the subject and spectator to open up a critical dialogue.

In her 2007 painting ‘Nous Étions’ (literally ‘We Were’) she depicts the head and shoulders of a black man with a fierce and steely look in his eyes. Compositionally and stylistically, there are parallels between this image and portraits by Rembrandt – particularly a work like ‘Two Negroes’, whose palette employs a similar burnt terracotta hue. The combination of the title and the citational nature of the painting suggests the inextricability of black subjects from the history of art. The phrase ‘Nous Étions’ could be completed in various ways: either as ‘We Were Here’ – staking out a place for British-Ghanaian artists such as Yiadom-Boakye in the discipline – or, more emphatically, as a retort to the viewer who seeks to erase black subjects from art history: ‘We Were!’ Many commentators have probed the political content of this exchange, with one critic in the New York Times suggesting that Yiadom-Baokye’s work is a twist on 19th century French impressionism that appropriates its aesthetic techniques while eschewing its tendency to ‘centre whiteness’, thereby unsettling the viewer’s expectations.

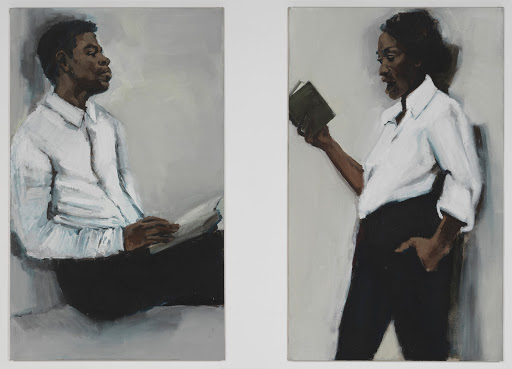

Yet this is only ‘political’ in the sense that all novelty is political: it requires some kind of cultural adjustment, some process of getting-used-to. The problem is, if the bar is low enough then novelty is easily won. Understanding Yiadom-Boakye’s work as an exercise in novelty reduces its value to merely changing Manet’s colour palette. Fortunately, her paintings contain more complexity and thoughtfulness than such readings would suggest. While some of them invite this narrow interpretation – engaging in an ironic cat and mouse game with the viewer – others reject that framework altogether. In ‘Brothers to a Garden’ (2017) and the diptych ‘Lie to Me’ (2018), the figures do not seem at all concerned with returning our gaze. What we see instead are characters absorbed in a form of life whose content is never fully disclosed to us. In such works, Yiadom-Boakye turns away from a critical commentary on racial politics and instead embraces a strange form of naturalism, depicting a world which is similar enough to our own to be recognizable, but too distant to be identified with.

Yiadom-Boakye has said of her imagined figures that ‘although they are not real, I think of them as people known to me. They are imbued with a power of their own… I admire them for their strength, their moral fibre.’ It would not be an interpretive leap to suggest that the attempt to conjure up such moral exemplars informs Yiadom-Boakye’s whole artistic outlook. Describing the contrast between her earlier and later work, the painter has stated that she went from ‘the sense of trying to illustrate an idea, to allowing the paint to bring something to life, or thinking about painting as a language in itself – that was the major shift.’ To ‘illustrate an idea’ is to inhabit a socio-cultural landscape in which the representation of a black person in a work of art is itself a form of statement-making. This is a boring game to spend one’s career playing, and in her more contemplative and less self-reflective paintings we can see Yiadom-Boakye’s attempt to avoid the straightjacket of an art which exists purely to ‘subvert’.

So averse is Yiadom-Boakye to the political categorization of her later work that she avoids most sociological and cultural markers. She even goes so far as to shun the mixing of male and female characters, remarking that ‘the conventional male/female dynamic is…a narrative that doesn’t interest me.’ Instead, Yiadom-Boakye seems to locate the moral exemplarity of her subjects in their independence. Sexuality is largely absent from her paintings, although sensuality abounds. In ‘A Fever of Lilies’ (2016), where a male and female figure look inquisitively at one another, the characters are separated by different canvases. A gaze that would have been an outward one, returning that of the beholder, becomes a reciprocal interaction between two characters existing in a space and time inaccessible to the viewer. This is a vision of genuine reciprocity. It is, as Andrea Schlieker remarks in the wonderful collection of essays and paintings celebrating Yiadom-Boakye’s latest retrospective, an image of each character ‘safeguarding the other in their autonomy.’

Yiadom-Baokye’s art thus gives the impression of trying to hold together two conflicting tendencies. On the one hand she seems to want – especially in her more recent work – to move away from the idea of an image as a statement, political or otherwise. On the other, this movement is motivated by a moral idea of what it would mean to live a genuinely independent and expressive life. To find this life she turns to a fictitious world, depicting figures who inhabit obscure and enigmatic roles. In a recent interview, Yiadom-Boakye remarked on the absence of concrete time and space in her work, observing that ‘sometimes when things suggest a particular time it becomes concerned with that, I don’t feel concerned with that. I don’t want to be concerned with that.’ Yiadom-Boakye’s concern is not directed towards the world, but towards the activity of her characters – who show what it would look like to live without the baggage of history. In this sense we could say that the true political content of her work involves an attempt to escape from a kind of hollow politicization. What is so enchanting about her paintings is that they present an image of freedom that feels both real and elusive, tangible and affecting yet impossible to fully grasp. It is as if she is trying to flee, entirely, from attempts at categorization. If this retreat is not possible in life then, at least, Yiadom-Boakye’s images show how it could be in art.

Read on: Zöe Sutherland, ‘Artwork as Critique’, NLR 113.