In December 2022, the International Brecht Society hosted its 17th conference – ‘Bertolt Brecht in Dark Times: Racism, Political Oppression and Dictatorship’ – at Tel Aviv University, in collaboration with Haifa University and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Having spent a lifetime crafting scenes rife with contradiction, Brecht would have been struck by the irony. A dozen Palestinian performing arts organizations issued a statement urging the society to reconsider. Hosting such an event at institutions entangled in the occupation, they contended, was ‘an affront to Brecht’s memory’ and would undermine Palestine’s struggle ‘towards freedom, justice and equality’. The conference went ahead. When some attendees travelled to Ramallah to try to meet with Palestinian artists and intellectuals, they were rebuffed. A year later, amidst its ongoing scorched-earth campaign, the Israeli military destroyed Gaza’s last theatre. Dark times indeed.

Images from Gaza flashed across my mind as I visited brecht: fragments, the largest collection of visual material from Brecht’s archive ever to be displayed. Spread across four floors of London’s Raven Row are journals, sketches, newspaper clippings, plot outlines, albums, manuscripts and other ephemera assembled by Brecht over the course of three decades. Enlivening this ‘laboratory of miscellany’ – as Benjamin once described his friend’s workroom – is an ensemble performance that roams the galleries, adapted from four little-known theatrical fragments written during the twilight years of the Weimar Republic. It’s a lot to take in, but what’s there has been judiciously selected. The title underscores the intent of the curators – to highlight the collages, the snippets, the scraps, and all things fragmentary in Brecht’s oeuvre. Its mix of archive and repertoire offers an insight into the working methods of an artist who did so much to define the parameters of communist art.

Framed and hung in the opening room are several manuscript pages from Brecht’s best-known visual work, War Primer (1955). Each page features a photograph from World War II, sharpened by a biting quatrain. Accompanying a portrait of Joseph Goebbels, for example, is the rhyming caption:

I am ‘the doctor’, I doctor what gets printed.

It may be your world, but I have my say.

So what? Its history gets reinvented.

Even my club foot seems a fake today.

Here, Brecht takes a potshot at the Third Reich’s chief propagandist, but the juxtaposition aims higher – skewering the truth pretensions of visual media. The family resemblance to the work of his Weimar comrades like George Grosz and John Heartfield is unmistakable.

Brecht, however, used collage and montage not just as artistic techniques; piecing together fragments was his method for researching, revising, and, crucially, reckoning with the shattered world around him. Most of the material included in brecht: fragments was not originally intended for public display. Enclosed in several glass cases a few feet away from War Primer are pages from albums Brecht compiled largely while exiled in America between 1941 and 1947. Shown here for the first time, these consist of large-format card sheets on which he pasted newspaper and magazine photographs in suggestive combinations. Among them are images of cities razed by airstrikes, bodies strewn among the rubble.

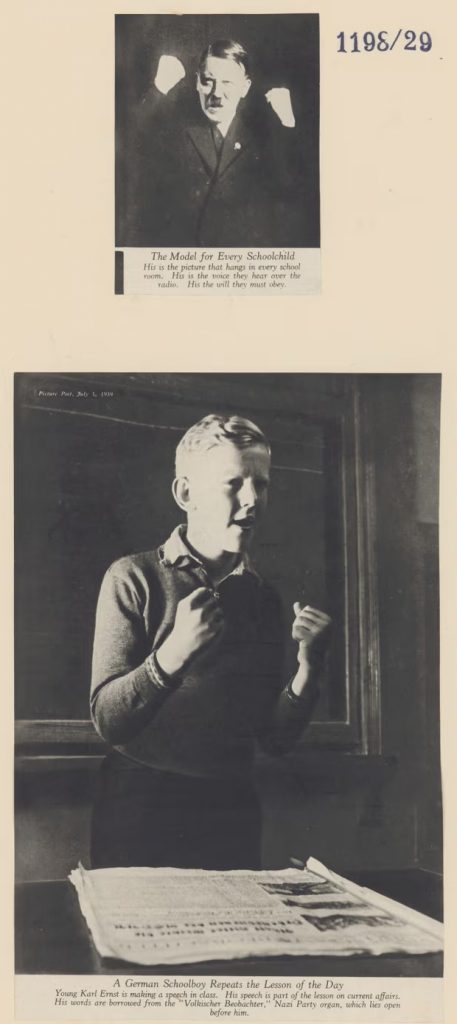

Many betray an interest in how social forms recur across different political contexts: an image of a Nazi frisking a Yugoslavian partisan is juxtaposed with one of Italian resistance fighters capturing a fascist; a frenzied crowd storming an American bank appears alongside a packed fascist rally; Bonnie and Clyde are paired with Hitler and Goebbels. Sprinkled throughout are scenes of collective struggle, from Calabrian peasants seizing farmlands to miners and women on strike. On one page, Hitler is seen furiously raising his fists just above a German schoolboy doing the same. The comparison infantilizes the Führer in the manner of a Heartfield collage. For Brecht, the assemblage was likely research into the gestural vocabulary of fascism that fed into his scripts and performances, such as the 1941 anti-Hitler play, The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui. This stemmed from his broader concern with the theatricalization of politics – also evident in the clippings of Mussolini, Roosevelt and Stalin on view here.

Annotated scripts and plot outlines displayed throughout Raven Row show that Brecht was as keen to cut up his own manuscripts as he was newspapers and magazines. Just as his epic dramaturgy maintained that each scene of a play should stand on its own, a similar principle governed his composition of such works. Individual lines, snippets of dialogue, entire acts – nothing was safe from Brecht’s scissors. He and his collaborators rearranged plays, poems and novels, slicing out fragments and pasting them in new places or even into other manuscripts. This practice allowed Brecht to view his ideas, quite literally, from different perspectives, and to adjust previous writing to changed circumstances. Like history itself, Brecht’s work was never finished.

In brecht: fragments we witness history through Brecht’s eyes as he navigated a turbulent age – from Weimar Berlin to his flight from Hitler across Europe, his wartime refuge in Hollywood, and finally, his return to a divided Germany, where he was wooed to East Berlin with the promise of his own theatre. Collecting fragments was a means of grappling with the dark times he lived through, but the archive can also be made to speak to our own. Below one journal entry, dated 5 April 1942, Brecht affixed a news clipping: a bereft woman, collapsed on a war-torn street in Singapore, screams silently at the wreckage, a lifeless child within arm’s reach. Above this grim scene, Brecht ponders whether writing poetry in the face of such misery amounts to anything more than ‘retreating into an ivory tower’. His concern echoes a question recently posed by Sarah Aziza in Jewish Currents about the deluge of distressing images from Gaza: ‘What does all this looking do?’

To write this review, I revisited my copy of War Primer and was surprised to find the same photograph from Brecht’s journal, now accompanied by a poem. In this path from collecting to publishing, we witness Brecht at work, conjugating an answer to Aziza’s question. That the exhibition sparks flashes of recognition would not have displeased Brecht. Like Benjamin, he conceived of history as an unruly conjunction of past and present. For the livestream from Gaza to constellate with the records of barbarism Brecht amassed is entirely in keeping with the point of his collection. As Sarah James writes in her contribution to the exhibition catalogue, Brecht left behind his vast archive of fragments not for the purposes of ‘memorialisation, but as collective resources for future collaborators’.

The exhibition attests to this in remarkable ways, particularly through the roving 90-minute performance that fills every floor of Raven Row. The curator and director Phoebe von Held has adapted four of Brecht’s unfinished dramatic works, staging them throughout the gallery to demonstrate how the repercussions of capitalist crises cascade onto the most vulnerable. On the top floor, a madcap scene from Fleischhacker (1924–1931) unfolds, about an unscrupulous speculator whose attempt to corner the wheat market triggers a global famine. We are then rushed down the stairs by a torrent of lines from The Flood (1926–1927), inspired by a 1926 hurricane that wiped out Miami. On the ground and lower ground floors, we meet those left to pick up the pieces: a family forced to abandon their farm due to Fleischhacker’s machinations, the shell-shocked tank crew of Fatzer (1926–1930), Mrs Queck, a single mother of five from The Breadshop (1929–1930), whose debts lead to her eviction and eventual death from despair. These fuming, quirky vignettes show Brecht at his most radical. He and his collaborators wrote them amidst the Wall Street Crash and Hitler’s rise, yet as we’re jolted from floor to floor, resonances with present realities hit home: engineered famine, forced migration, cities reduced to rubble.

Von Held holds this sprawling world together with glue and tape. lambdog1066, one of London’s most inventive costume designers, has dressed the ensemble in maximalist attire collaged from rubbish. Nearly all props and set pieces are fashioned out of cardboard, including the large backroom where The Breadshop unfurls, which is covered in tiles made of shipping boxes, their address labels and Amazon logos still visible. Every directorial choice appears to have been made with fragmentation in mind; even the audience is split in half at the start and sent through the performance in opposite directions. The dozen actors constantly switch roles, flipping through characters like a stream of TikTok videos. One moment they’re with the Salvation Army, the next they’re playing in a bluegrass band. They portray cops, reporters, Deliveroo workers, biblical prophets, as well as less conventional dramatis personae like bull markets and cities on the brink of destruction.

After the performance, I returned upstairs to Brecht’s journals. An entry from October 1943 shows a photograph of a building in Aldgate – a stone’s throw from Raven Row – its façade blown apart by a German bomb. On the ground floor of the ruins, a vaudeville act is being performed to a small audience. It called to mind the destroyed theatres of Gaza and the West Bank. One such theatre, the Said al-Mishal Centre in Gaza City, was levelled on 9 August 2018 by an Israeli airstrike. Days later, Gazans set up white plastic chairs before the rubble, and performers climbed atop the jagged concrete and steel to stage a mournful remembrance. One young actress avowed: ‘We will rebuild it. They think they destroyed the building. Will they stop us? No. We will never stop. We can act in the street. We can act on the sand.’

Read on: Roberto Schwarz, ‘Brecht’s Relevance: Highs and Lows’, NLR 57.