Here is the first throw of our three-sided die: Surrealism is an accidental codex of invocations that pairs well with materialism. Second toss: Surrealism made sense of sleeping horror (dreams) after Dada made sense of waking horror (war). Last toss: Surrealism is the unconscious response (Freud) to material pressure (Marx). Let’s just say that there are no Surrealist cops and put away the dice. (I feel certain that there are Impressionist cops but cannot prove it.)

Our timeline begins in 1920, in Paris, with the publication of André Breton and Philippe Soupault’s The Magnetic Fields, a weeklong writing session that they published without (allegedly) the benefit of revision. The idea of this ‘automatic writing’ was to bypass any gatekeepers of the mind, and that impulse had wide appeal. Surrealism spread almost as fast and far as photography, to which it also responded. If the recording of facts had been subsumed into the work of the lens, what was left? Surrealism’s answer was the right one: give voice to sensations above and below language and let the movement of the spirit guide the material. As German critic Wolfgang Grunow described it in 1928, Surrealism is ‘idea-photography’. The reverberations of this approach have been deep and wide, many of them complicating the very idea of Surrealism being a single idea. In 1967, Martiniquan poet and revolutionary Aimé Césaire said that ‘Surrealism interested me to the extent that it was a liberating factor’. In 1968, the Chicago Surrealists made common cause with Detroit and Paris and preached the power of both Bugs Bunny and the Black Panthers.

Surrealism Beyond Borders, just finished at the Met in New York and arriving at London’s Tate Modern this week (co-curated by Stephanie D’Alessandro and Matthew Gale, along with Lauren Rosati, Sean O’Hanlan and Carine Harmand), is an attempt to write some of this sprawl into the timeline and decenter Paris. The proper Surrealist response to an institutional show is probably to switch all the wall texts (and please don’t tag me if you do). The work here stretches from the twenties to the seventies, and is organized into small thematic clumps, which come in different categories. There are ideas (Revolution, the collective, ‘scientific Surrealism’), places (Chicago, Cuba, Cairo) and material varieties (dreams, objects – Dali’s Bakelite telephone host and its plaster lobster guest is one of the only dorm room hits here). That this all succeeds will be obvious to even a sleepy visitor. If it is not too late or too meek to look for something as evanescent as fun – the original revolution? or simply as evanescent as revolt? – this show is stocked with it. I returned to the show several times; it had become a second tinnitus. Did I return in hopes that I could make it stop, that the art might cancel itself out and die down?

Marcel Jean’s Armoire surréaliste (1941) is the perfect doorman, blending the obviousness and mystery that drives so much Surrealism. It’s exactly an armoire, with a real wooden body and unreal, painted doors swinging open to reveal a view of, depending on my mood, hills or clouds or the ocean. The corny bits of Surrealist art are often my favourite, the moments where representation clings to itself and lets a dream melt the frame.

Cuban painter Wifredo Lam is the exhibition’s menacing docent, whose work makes good on his claim that he could ‘act as a Trojan horse that would spew forth hallucinating images with the power to surprise, to disturb the dreams of the exploiters’. His towering canvas, Le présent éternel (1944), is a beige riot of elbows and beaks and bodies that throws Picasso back into the ocean. I fell hardest in love with his elegant black-on-yellow line drawing for the cover of Aimé Césaire’s Cahier d’un retour au pays natal (1939), a two-headed alligator with a flowered tail and a bridge for a body. Lam shares a psychic charge with American painter, Ted Joans, also a friend of Breton’s. His 1958 canvas, Bird Lives!, turns Charlie Parker into a hulking animal silhouette vibrating black on white. Joans is also responsible for a thirty-foot long paper work called Long Distance, a cadavre exquis conducted over thirty years with dozens of artists and writers. William Burroughs almost refused to participate because he didn’t draw or doodle unless he was on the phone, so Joans stayed on the line with him while he scribbled (literally) his panel.

I came back the fourth time for Remedios Varos’s triptych, reunited here for the first time since its Mexico City debut in 1961. The three paintings – ‘To the Tower’, ‘Embroidering the Earth’s Mantle’, and ‘The Flight’ – depict a set of girls who bicycle away from a convent to work on a tapestry in a tower. In the final panel, a girl surfs on a sea of coppery foam with her friend. In a notebook, Varo wrote of the first painting: ‘Their eyes are as if hypnotized, they hold their knitting needles like handlebars’, which is an odd note, since they do appear to be holding handlebars attached to their hairline bicycles. ‘Only the girl in the front resists the hypnosis’, she writes. Varo notes that while embroidering the ‘earth’s mantle’ in the second painting, this awake girl weaves a ‘ruse’ into her fabric, which enables her to escape with her ‘beloved’ in a ‘special vehicle’, which I maintain is an umbrella turned upside down.

These are the paintings that Oedipa Maas and Pierce Inverarity see in The Crying of Lot 49. Varo is described as a ‘beautiful Spanish exile’ and the subjects are ‘frail girls with heart-shaped faces, huge eyes, spun-gold hair’. What stuck with me is Pynchon’s description of the middle painting, of the girls weaving the tapestry in the tower: ‘All the waves, ships and forests of the earth were contained in this tapestry, and the tapestry was the world’. The larger world is often under-discussed in the conversation around Surrealism and the church, which Surrealism simultaneously replicated and replaced. (Breton is often referred to as ‘the Pope’.) That the Varo triptych looks like a series of frescoes is no minor parallel. The early twentieth century saw religion explicitly detached from religion. The soul had to go somewhere to work, and Surrealism was one of the safest harbours.

Connecting this revolution to the one waged with rocks and bodies is slower work. The relevant effect of Surrealism Beyond Borders is to establish adjacency rather than unity as the necessary condition for art and politics to feed each other without restraint. Placing Surrealism in the vicinity of emancipatory work isn’t hard because, as nebulous cohorts go, Surrealists generally favour the right side of history. Haitian historian and novelist Roger Gaillard wrote that Breton ‘helped create, beyond any doubt, a climate among young people of my generation, a confidence in ourselves and in the future’. Haitian poet René Bélance said that while Breton ‘had no intention of disturbing the political order of a country which was not his own’, the ‘banal fact was that to speak of liberty – at that moment – was certainly a subversive act’. In 1945, a reporter suggested that Breton ‘had a hand in the Haitian revolution’, to which Breton responded, ‘Let’s not exaggerate’. ‘At the end of 1945, the poverty, and consequently the patience, of the Haitian people had reached a breaking point’, Breton said, and the Haitians largely drew their ‘vigour from the French Revolution’. Even the problematic father knew the order of revolutionary events.

Resistance was a part of the Surrealist project from the beginning. The Surrealists supported the Rif rebellion in Morocco and became involved in various anti-colonial activities, chief among them a friendship with Aimé and Suzanne Césaire. The decentering of Paris has also been around as long as Surrealism itself, it turns out. Etienne Lero, in 1932, and Suzanne Césaire, in 1942, (in the Paris-based, Martinique-driven Legitime Defense and the Martinique-based Tropiques) both contended that literature that remained ‘tethered to French stylistic rules could not adequately represent the reality of Antillean life, culture, and landscape’, as Annete K. Joseph-Raphael describes it in her essay for the exhibit catalogue. Even while rejecting the Parisian tilt, both artists ‘explicitly claimed Surrealism as an antidote to the poisons of colonial violence and cultural assimilation’. Surrealism, then, doesn’t necessarily need Breton, or even Surrealism. This is where the art-historical gives way to the material. You can leave behind a set of shared references and friends and move towards action: surrealizing rather than Surrealism, a practice that predates the artform and exists as a layer of consciousness rather than an affiliative tendency.

In January, at the close of the exhibition’s run at the Met, Fred Moten and Robin D.G. Kelley talked over Zoom with Zita Cristina Nunes about Black, Brown, & Beige: Surrealist Writings from Africa and the Diaspora, an anthology of Black Surrealism published in 2009 and co-edited by Kelley. After almost an hour of discussion, Moten played songs by George Clinton and Klein, and Kelley moved to the heart of the action. ‘For black artists, Surrealism was less a movement to join than a set of practices they recognized as deeply grounded in African and Afro-diasporic culture’, he said. ‘They found in surrealism more of an affinity than an ideological commitment, more recognition than revelation’. In his essay for another anthology, the forthcoming Get Ready for the Marvelous: Black Surrealism edited by Adrienne Edwards, Kelley paraphrases ‘Suzanne Césaire paraphrasing André Breton: “Surrealism will be political or it will not be.”’ He also contends that ‘the key words undergirding Surrealism are not reality, or the Marvelous, but FREEDOM and REVOLUTION’.

That freedom, over time, has morphed, just as Surrealism itself began as a writing exercise and turned into a way of seeing. One of the most relevant freedoms now is the freedom from work itself. In November, at the second annual conference of the International Society for the Study of Surrealism, writer Abigail Susik led a panel on Charles Fourier and laziness, a gloss on her new book, Surrealist Sabotage and the War on Work (2021). It was uncanny, but not surreal, to attend a surrealist conference on Zoom during the pandemic and see that the ministrations of Parisians one hundred years ago had become not just fashionable but relevant. Susik wrote an editorial that appeared, in slightly different forms, in both The New York Times and the Washington Post this year. I enjoyed seeing Susik discussing ‘permanent strike’ in Bezos’s paper, and quoting a Surrealist proclamation from the 1925 pamphlet, Surrealist Revolution: ‘We do not accept the laws of economy or exchange, we do not accept the slavery of work, and on an even wider scale we proclaim ourselves in revolt against history’. (The Times version was more conservative.) Susik begins her continuum of refusal with the labour shortages after World War I – the context for Surrealism 1.0 – and connects it to the current ‘lying flat’ movement in China.

‘It is remarkable that the post-pandemic labour shortage and “Great Resignation” we are seeing right now in the United States resembles in significant ways the post-pandemic world that the surrealists confronted in the early and mid-1920s’, Susik told me. When France was recovering from a severe postwar labour shortage that had lasted for years, ‘the surrealists refused to comply’, she said. ‘They pulled the ultimate “big quit”’.

An actual dialectic, a deep, political connection that neither settles nor determines, was there from the start. Breton was engaging with socialism and Marxist thought before Surrealism officially began. In 1924, he was talking with the young Socialists of Clarté magazine, engaging, arguing, and trading spicy editorials. Breton and Aragon joined the French Communist Party in January of 1927 and then proceeded to have a series of splits over time with each other and the party. Pierre Naville, a Surrealist who stayed committed to Communism, reflected about all of this in 1989: ‘Indeed, the attitude of the Surrealists scarcely depended on their relationship with political goals, in the practical sense. The majority of them, Breton foremost, were concerned primarily with literary success’. I asked Alan Rose, author of Surrealism and Communism: The Early Years (1991), how this played out. ‘Naville, more than any other group member, understood why Marxism could not accept surrealist principles and was far ahead of the group in endorsing a Trotskyist, rather than Stalinist approach to world revolution’, Rose said. ‘For Naville, the political change preceded the artistic one’.

And at the time, years before Haiti, Breton lived up to the picture that Naville gave us. In the Second Manifesto, written in 1930, Breton wrote, ‘Surrealism is not interested in giving very serious consideration to anything that happens outside of itself, under the guise of art, or even anti-art, of philosophy or anti-philosophy – in short, of anything not aimed at the annihilation of the being into a diamond, all blind and interior, which is no more the soul of ice than that of fire’. This is the syllabus Breton, the better-known version, the Hegelian hothead who was generally opposed to authority even as he accrued it.

There are plenty of reasons to think surrealizing and Surrealism are both healthy now, fulfilling the purpose Michael Löwy described in 2001: ‘a movement of the human spirit in revolt and an eminently subversive attempt to re-enchant the world’. Long associated with American Surrealism, Will Alexander recently published a new book of poems, Refractive Africa (2021), anchored by a long piece called ‘THE CONGO, For the resistance rendered by Casimiro Barrios & Fela Kuti’. Alexander has the same ability to combine states of being and perception as Cesaire and Aragon: ‘as Congolese we replicate the impossible / our physical structure seemingly capable of the bizarre / in Western terminology we remain a dazed compounding / where our body gains no equated merit of itself’.

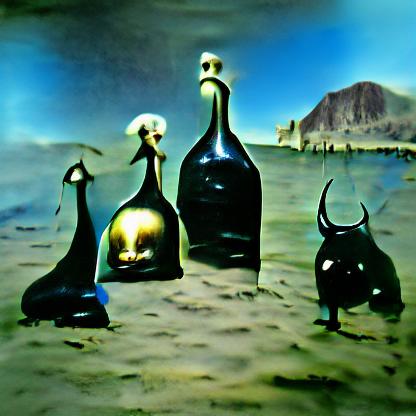

I see a great deal of surrealizing on Instagram and TikTok, where accounts like @Succ.exe and @onylshitpostsIG mash together sound and image for sequences that tell no linear story and can barely be explained. Two electric drills, joined at the bits, dance on a garage floor to a soundtrack of farts. Post it! Or you can go to hypnogram.xyz, and let AI make you a personalized exhibit. This was what the prompt ‘dark bottle animals Dali’ spat out:

The last time I saw the Met exhibit, I went with Sarah Leonard, publisher and co-editor of Lux. While we walked around, she said that it was a relief to see something in a museum that made her laugh. I emailed her after the show to ask if Surrealism seemed like it had any kind of organic relationship to the work of emancipation. ‘The element of surprise and delight in surrealism feels like a taste of the world I’d like to live in, or like class struggle through the looking glass’, she wrote back. Leonard also reminded me that Angela Carter loved surrealism. ‘She always said that we needed both Marx and Freud’, Leonard said, ‘and I agree’.

Read on: Michael Löwy, ‘Surrealism’s Nameless Soldier’, NLR 29.