As a boy, I was fascinated by Sherlock Holmes.footnote1 He took drugs, of course—very shocking—but he was extremely clever. I was struck by what he said to Watson, who was rather dim: ‘When you’re searching for the solution to a problem, don’t look at what you can see. Look at what you can’t see.’ When I became a scholar and a teacher, the first thing I would tell my students was: ‘Look at what’s in front of you, but think about what is missing.’ And then some very interesting things start to happen. In the struggle for political power in Thailand between the Reds and the Yellows—which has been going on for fifteen years, getting hotter and hotter, more and more violent, with huge mobilizations and heated oratory—I noticed something that was missing.

The language used by both sides is very ugly. For example, Yingluck Shinawatra, Thailand’s first female prime minister, was always called a prostitute by the Yellow Shirts, who said she was very stupid and just a puppet for her brother, Thaksin.footnote2 The labels applied to men are equally harsh: reptile, idiot, gangster, homosexual, traitor, coward, dirty dog, corrupt, uneducated—all kinds of things. But there is one word that doesn’t appear, even though it’s rather mild: jek. This is the old expression for an overseas Chinese. If you are in the Thai countryside, you will see signs that say ‘nice jek restaurant’, and nobody is upset about it, although the rich, bourgeois Sino-Thais don’t like to use the term. So why is it not part of the political discourse? Strikingly, another term has become very popular in the last thirty years or so: lukchin, which means son or child of a Chinese. Students and intellectuals who belong to the Chinese diaspora have begun asking to be referred to in this way. Thailand is full of minorities, fifty or sixty at least, but they never call themselves child of this or child of that.

Journalists and scholars, both foreign and local, have put forward a number of explanations for the hatred and the violence of Thai politics: it is a struggle between dictatorship and democracy, conservatives and populists, monarchists and republicans, honesty and corruption—or between one class and another. These explanations are partial at best, and none of them captures the whole truth. Another theory speaks of Bangkok arrogance pitted against the rest of the country, which certainly has something to do with it. But in itself this cannot explain the most striking aspect of the whole political struggle, which is the regional distribution of support for the Reds and Yellows. The south is completely in the hands of the latter; Bangkok is also solidly Yellow; but the north and north-east of Thailand are Red strongholds. There is no explanation in terms of class conflict that can truly account for this polarization, and it has nothing to do with democracy either. Commentators do not talk about this regional dimension, even though it has been evident for a long time.

An encounter during a visit to Thailand encouraged me to think about this question. I was travelling to the airport in Bangkok; the taxi driver was an elderly Chinese man from the local Chinatown. We began talking about the political situation, and I asked him who he supported. He said, ‘Of course, I support Thaksin’, the leader of the Reds. Was it because he liked his policies, his attempts to provide greater social support, health care for the poor and so on? ‘No, the reason I support him is because he is a Hakka like me. We Hakkas are the only honest people in Thailand today. We work very hard, we had the courage to fight against the Manchu, we didn’t torture the feet of our women, we’re not pretentious.’footnote3 I then asked his opinion of Abhisit Vejjajiva, the leader of the Yellow camp, whom he dismissed as a ‘goddamn Hokkien’; members of this group were lazy and not to be trusted in their dealings with others. My driver was equally hostile to Sondhi Limthongkul, another very important political figure.footnote4 ‘He is Hailamese. Those people are so dirty, they never even wash; they’re ignorant, stupid and cruel.’ At this point I plucked up the courage to ask him about the King: ‘He is a Teochew, and they are opportunists who always suck up to people more important than them. They are cowards, who only came here because they could not land in Vietnam or Indonesia or the Philippines.’ Finally I asked him what he thought about the rural Thai. ‘They are nice people, but they are quite different from the Chinese; they are happy as long as they have good food to eat, plenty of alcohol, and plenty of sex. They have no politics.’ ‘Doesn’t this mean’, I said, ‘that your view of Thai politics is like the Romance of the Three Kingdoms—the classic Chinese novel of feuding warlords.’footnote5 He agreed that it was. So the four main players in Thai politics all came from one or another of the Chinese diaspora groups, and my taxi driver hated three of them, but not his fellow Hakka, Thaksin.footnote6 This led me to wonder about the identity of the overseas Chinese in Thailand, and where exactly they fit into Thai society.

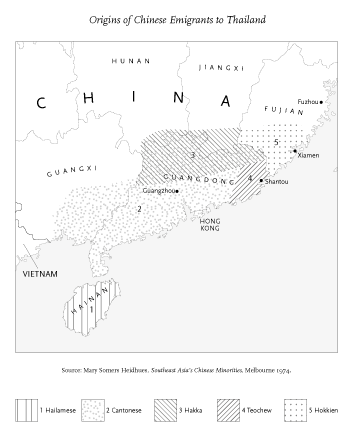

The story begins towards the end of the Ming dynasty, when the last and bravest enemies of the Manchu started to flee from places like Guangdong and Fujian in southern China. They knew they had lost the battle and could anticipate what punishment would be meted out to them, so they left the Middle Kingdom altogether. The Cantonese mostly worked their way down the coast to Vietnam; the Fujian or Hokkien people went further, to Cambodia, Indonesia and the Philippines; the Teochew followed them. The Hailamese and the Hakka came a century later.footnote7 Of course, we know very little about what the people who left China at that time actually thought about their own identity, as most of them were illiterate. There is an illustration of this from the early days of Spanish colonization in the Philippines. Fujian traders went back and forth between Manila and Guangdong, making a good profit from their journeys. The Spanish asked them who they were, and the traders replied, ‘We are sengli’. In their own language, that simply meant traders or merchants. But the Spanish thought it was their ethnicity, so well into the nineteenth century they referred to the traders as sangleyes, until someone pointed out that they should change the word to chino. If those people simply identified themselves as traders and said nothing about being Fujian or Chinese, that suggests that they had little sense of belonging to a larger group; their identity merely encompassed their families, their local villages and so forth. It took a long time for that to change.

The exodus from China was followed by another very important development. The modern history of Siam begins in 1767, nine years before the United States declared their independence from Britain. In that year, a huge Burmese army sacked, looted and burnt the ancient capital of the Ayutthaya kingdom. Much of the vanquished realm then fell under Burmese occupation, and Siam went through years of chaos and devastation. The whole native aristocracy of the old regime was obliterated. In time, a militarily gifted Sino-Thai, known today as Taksin the Great, began driving the Burmese out, making use of experienced Chinese sailors who had settled in south-eastern Siam. Taksin is still greatly venerated in Thailand, but he proved to be rather cruel and paranoid once he had declared himself king. After a reign lasting fourteen years, he was overthrown in 1782 in a palace coup by one of his generals, and executed along with all of his kinfolk. The general who replaced Taksin founded the Chakri dynasty, which has lasted to this day; he made Cambodia into a Siamese vassal state, and is known to posterity as Rama I.

Taksin had been the son of a Teochew man and a local woman, and his replacement was also of Teochew stock. This was the only example anywhere in Southeast Asia of an overseas Chinese becoming the local monarch; Taksin actually applied several times to Beijing for recognition, but the rulers of China were very reluctant to grant it to him, because they did not like the idea of a Chinese king outside the Middle Kingdom itself. He did everything he could to encourage his fellow Teochew to come to the new capital, which was a port city where trade expanded very rapidly. This capital was effectively the forerunner of modern Bangkok. Having a king of their own marked a huge advance for the Teochew, who had previously been regarded by the other Chinese communities as small and insignificant. They became the dominant group among the overseas Chinese in Siam; they married into high families, and were given important jobs at the Court. Well into the nineteenth century, the Chakri monarchs continued to use a red seal that came from the Chinese Zheng clan for important state documents.footnote8 Only with the rise of nationalism did it become embarrassing to admit that the king might be an immigrant, and the Chakri began to conceal the Sino-Thai origins of their dynasty.

The Hokkien, who, like the Teochew, had been concentrated in Chanthaburi, close to the modern Thai–Cambodian border, now began to move towards the west coast of southern Thailand, attracted by the growth of mining in this region. They also spread further south, into Penang and Singapore. Events in China precipitated further waves of emigration in the nineteenth century. The colossal Taiping Rebellion led to tremendous violence, especially from the generals who were sent to crush it, and caused a huge upheaval throughout southern China. It was at this time that the Hakka began to come, hoping to escape from the Manchu. They settled at first as farmers in an area west of Bangkok, near the Indian Ocean, thinking they would be safe there from anything that the Manchu might do; later they moved to western Thailand. The Hailamese travelled in the same direction, but went right down to the south. Although they were the poorest of all these groups, the Hailamese had one great advantage: they were immune to tropical diseases. Thailand’s southern area is still controlled today by Hokkien and Hailamese, and all the leaders of the Yellow Shirts come from this region. Periodically the Manchu would announce that anyone who had left China and wanted to come back would be summarily executed if they returned, so there was little incentive for them to do so.

The most important of the overseas Chinese in Thailand, who had close ties with the monarchy, managed the country’s trade and reaped the benefits from a monopoly held by the Court. But in 1855 the British arrived in Bangkok and issued a flat ultimatum to Rama IV, ordering him to break up the royal monopoly. This particular diplomat, John Bowring, is best known outside Thailand for having coined the slogan ‘Free trade is Jesus Christ, and Jesus Christ is free trade’. The Court’s trade monopoly was broken, which made things difficult for those Chinese who were used to working under royal patronage. It was also at this time that Britain forced open the southern Chinese ports in the Opium Wars. Colombia’s role in the contemporary drugs trade is nothing compared to the scale on which the British operated: all down Thailand’s western shore, as far as Penang and Singapore, the major import was now opium from British-ruled India. A new system had to be devised for handling the trade, based on tax farmers, who would be given the right to extract as much tax as they could from the local population, in return for a fee which they paid to the ruler. Of course, they would have to be very wealthy to pay for the license in the first place, but once they had it, it could be very lucrative indeed. The overseas Chinese who got hold of these tax farms also needed a lot of labour, tough young men to protect their territory and make sure that the boss got everything he expected. The opium trade was so successful, at least for the Court, that from the 1870s until the mid-twentieth century, year on year, about 50 per cent of the state budget came from opium.

During the reign of Rama V, which lasted from 1868 to 1910, there was a policy to encourage the immigration of poor, illiterate Chinese to work on commercial sugar plantations, or to build port facilities and a new transport network of roads and railways. The King’s policy closely followed the path of the British in Malaya and the Dutch in Sumatra; he was shrewd enough to realize that by importing workers from outside the country, he would avoid disturbing rural, semi-feudal Thai society too greatly. As a result, the country’s first working class was almost entirely Chinese, and it remained this way until World War Two. Initially, the Chinese were not allowed to consume opium, but for lonely, desperate young men working on construction projects, it was hard to resist such temptations. It was also a clever way for the bosses to keep their wages inside Siam; there was a tax farm in alcohol, a tax farm in prostitution, a tax farm in gambling. Most of these young men, if they did not die quickly, ended up very poor, and their money went into the pockets of the tax-farm organizations. There was a struggle over the control of opium among the secret societies that people in Thailand call ang yi, whose bosses would use some of the young men from their own groups as muscle, to beat or kill anyone who threatened the various tax farms.footnote9 Since there was always friction between the boss in one place and the boss somewhere else, there was an incredible amount of violence as these secret societies fought one another, even burning down each other’s towns, right up to the end of the nineteenth century. These were very dangerous groups of people, accustomed to fighting with every conceivable method. The whole phenomenon was only brought under control by one of the British policemen who had already organized the suppression of secret societies in Singapore. Officially the ang yi more or less disappeared; in reality they persisted, and would surface again during the Great Depression.

Twentieth-century pressures

The fall of the Chinese monarchy in 1911 came as a huge shock to people in Bangkok. It was followed by an astonishing general strike of Chinese workers and merchants in protest against new taxes that had been imposed by the fun-loving and spendthrift Rama VI. Shortly afterwards, the King published two pamphlets under a pen-name, one of which described the local Chinese as ‘the Jews of the East’, with the other appealing to the Chinese themselves not to be influenced by Sun Yat-sen’s nationalism and to remain loyal to the Throne. In the decades after World War One, there was another huge influx of migrants from China. About 100,000 people came to Bangkok each year, a far bigger influx than anything that had happened before. But it didn’t really change the basic distribution between the groups.

In Bangkok, for example, the Teochews controlled 97 per cent of all pawn shops, and a similar proportion of rice mills; they also accounted for 92 per cent of Chinese medicine people. Sawmilling for the timber trade was overwhelmingly in the hands of Hailamese: 85 per cent. People who specialized in the leather business, on the other hand, were 98 per cent Hakka, and nine out of ten tailors were Hakka, too. Some 59 per cent of Bangkok’s machine shops were Cantonese-owned; 87 per cent of rubber exporters were Hokkien. So these Chinese communities were very sharply distinguished by occupation; the dominant ones especially did everything they could to make sure that the others wouldn’t come barging in, wanting to have a few rice mills or pawn shops of their own. There was quite a lot of tension. But one advantage of this period was that with the creation of the railways and the road network, it was possible for people to move much further away from the centre than before. The railway that ran up to the very north of the country started to draw Hailamese and Hakka. Thaksin, the Red leader, is a Hakka whose grandfather had travelled north, almost to the Laos border.

The 1930s were a difficult time for the overseas Chinese, because there was a lot of pressure on them to help during the Japanese invasion of China and the hideous occupation that followed. A struggle developed between those who supported Chiang Kai-shek and those who sympathized with Mao Zedong. The richer, more successful members of the diaspora were closer to the Nationalists, while the others tended to lean towards Mao and the Communists. It posed a question for all the new arrivals: what are you going to do about your identity? There was pressure in one direction to say they were just Chinese people who happened to be abroad, in the other to say, ‘We can be successful and do well here, perhaps we should be loyal to the country in which we’ve settled.’ This question has never been fully resolved. After World War Two, the loyalty of many Chinese to the system in Thailand was questioned. The country’s rulers were no longer absolute monarchs; power had now passed to the military. The army, police and intelligence services distrusted the Chinese, seeing them as potential spies or troublemakers, and they were often harassed. In fact, the founders of the Thai Communist Party were essentially poor people, workers from Bangkok and the surrounding area, who did not set about guerrilla activities until the mid 1960s.

By this point, the economy of Thailand was almost entirely in the hands of different Chinese-speaking groups—but not its political system. These groups lacked real political influence, especially under the military dictatorships. Many overseas Chinese wanted their children to be something more than business people: to become lawyers, doctors, judges, teachers and bureaucrats. Business was not regarded as a high social occupation: better to have a title, to be Doctor of this or Professor of that. One reason the Chinese tried to establish close ties with the Thai monarchy was the hope of obtaining feudal-style titles in return for funding some of its activities. Second-generation Chinese often sent their children to study in British and American universities. During the Cold War, the Americans decided that Thailand needed more universities: there were only two, and they were very hard to get into. Within five or six years, universities were built all over the country, and the total number of students rose from 15,000 to more than 100,000. This created more opportunities for everyone in Thailand, but especially for the overseas Chinese, who could now go to university at home, having had no real chance of doing so before. For a long time, the monarchy showed itself to be quite cunning. In the national museum in Bangkok there is a lovely photographic exhibition of the history of Thailand, but there are no Thai people in it at all—just the names of four kings. Thailand has no national heroes, which is rather striking; but it made it easier to absorb the Chinese immigrants. Things started to come apart when the military regime collapsed in 1973 and the top generals had to leave the country. There was a huge popular uprising in Bangkok, supported by people from almost every class, and for the first time a genuinely democratic government was established. Elections followed, with socialists and liberals winning seats in the national parliament.

This was the pivotal moment in the long reign of Rama IX, who had ascended to the throne in 1946. Soon afterwards, American Indochina collapsed, the Lao monarchy was abolished, and communist states ringed Thailand’s eastern borders. This fed paranoia in royalist circles about the future of the monarchy, and the King called in the brutes. In 1975–76, right-wing activists began killing leftist politicians, students and union leaders. On 6 October 1976, organized mobs—including members of the Border Police, whose sponsor was the Queen Mother—attacked Bangkok’s Thammasat University and set about murdering students in broad daylight. More than a hundred people were killed; bodies were strung up in the city’s biggest park, bearing the marks of hideous torture. Needless to say, no one was punished for these crimes. A military coup took place that night with the blessing of Rama IX, who insisted on choosing his own prime minister, a rabidly anti-communist judge. Hundreds of students fled Bangkok to join the communist maquis in distant parts of the country. Eventually most of these young people returned to the cities when the Thai Communist Party was betrayed by Deng Xiaoping, in pursuit of an alliance with Thailand against the Vietnamese.footnote10

Since the demise of the communist movement and the end of the Cold War in Asia, there have not been any left-wing parties in Thailand; all of them are conservative and neoliberal. It was a perfect time for the bourgeoisie, Chinese or otherwise. One sign of this was a huge expansion of the banks: they now had branches all over the country, their buildings often bigger than those of the provincial governors. For those who wanted to go into politics, especially the Chinese, this was ideal; they could borrow plenty of money to pay off the people who were helping them. These individuals became something like small warlords, who had interests in real estate, gambling, smuggling and so on, and were effectively immune to local police forces. They were very eager to become members of parliament, where they would have many opportunities to secure higher jobs and funding for projects of various kinds. They were perfectly happy to move from one party to another as required. This was the first time that anyone thought it worthwhile to become a politician in Thailand. These ‘representatives’ had to rely on their own families in the incessant power struggles, and the top politicians filled every possible job with relatives and close friends, as they still do today. In this period, when small businessmen became much larger businessmen, they used exactly the same methods as the ang yi of earlier times. In the 1980s and 90s, for the first time since the nineteenth century, killings were going on in Thailand which were not vertical: it was not a case of the state repressing the left, it was businessmen who wanted to be politicians feuding with their rivals, with assassinations by hired gunmen, ambushes and bomb-throwing.footnote11

Rise of Thaksin

Then came the Asian crash of 1997–98, ignited by developments in Thailand. The baht lost half its value, the Crown Property conglomerate suffered heavy losses, and the national economy was devastated. It was amidst this turmoil that Thaksin Shinawatra started his meteoric rise. A former policeman of Hakka origin, Thaksin had become one of Thailand’s richest men thanks to a near-monopolistic mobile-phone concession which he obtained under the last military regime. After founding his Thai Rak Thai (Thais Love Thais) party, he recruited a batch of ex-leftists who had been part of the maquis and were eager to become leaders at long last. Thaksin announced a series of ‘populist’ policies aimed at the masses, such as low-cost health care and the cancellation or deferment of farmers’ debts. He became the first Thai politician to win a controlling majority in parliament, and has won every election since by a decisive margin—even from exile. The other novelty was that he actually honoured his campaign promises. Huge sums of money from the now-recovering Thai exchequer completely outshone the ‘royal development projects’, and the Palace began to feel threatened. Even the fact that Thaksin’s name was so close to that of King Taksin the Great, who had been executed by the Chakri dynasty, caused the royals some anxiety. They turned to the predominantly royalist and conservative judiciary in the face of Thaksin’s control over the executive and legislature, and eventually to the military, which overthrew his government in the coup of September 2006. The new military regime was mild compared to its predecessors, but achieved nothing other than to have Thaksin tried in absentia and sentenced to two years in prison for corruption. When fresh elections were held, a repackaged version of the Thai Rak Thai party won again, and two proxies of Thaksin served as prime minister. They were ousted in turn by militant opponents, the so-called Yellow Shirts, who claimed to be defending the monarchy; a ‘palace nominee’ took over, and was opposed by the mobilization of Red Shirts.

In the struggle between Thaksin and the Court, the latter made some grave errors, betraying the weakness characteristic of dynasties in decline. The first was to arrange for an astonishing media campaign that would have made Kim Il Sung blanch. It is hard to find a public space anywhere today that does not have endless billboards with images of the King. ‘Beneficent royal activities’, such as charitable works, ceremonies and memorabilia of the King’s youth, were greatly expanded—not always in the best of taste. In his prime Rama IX had not needed any of this, as he was genuinely popular. Their second blunder was the unscrupulous expansion and deepening of the lèse-majesté laws, which are now the most repressive in the whole monarchist world: you can easily go to jail for twenty years. The royalist politician Sondhi was given a two-year sentence just for repeating comments made by one of Thaksin’s supporters, even though he was denouncing her for criticizing the monarchy. Tens of thousands of websites have been suppressed—in vain, as the disaffected young are far more technologically skilled than their enemies, elderly bureaucrats for the most part. Blogs openly hostile to the Palace have increased enormously over the last decade. The problem of succession, inherent to any monarchy, is becoming more and more obvious to the general public. The King is now 88 years old, and has been repeatedly hospitalized. The billboards tell another (unacknowledged) story: the vast majority of pictures show the King alone, save perhaps for his favourite dogs, from youth to old age. His wife and children only appear in ceremonial photographs. The Queen has lived a life of her own, while the rarely seen 63-year-old Crown Prince has no popular standing at all, and the absence of homey, father-son images betrays the profound dislike between the two men. For varying reasons, the three royal daughters are all implausible candidates for the throne. One might have expected the elderly ruler to firmly announce his choice as the next monarch, but for decades there has been nothing but silence. It is often said that King Taksin the Great, as he awaited execution, prophesied that the Chakri dynasty would expire with its tenth descendant. A myth, of course, but one that lingers and bites.

Who are the fanatical royalists? One might have expected that they would come from the capital’s bourgeoisie, but this would be to overlook the crucial factor. Over the past fifty years, almost every Thai prime minister has been a lukchin, like the monarchy itself. But this shared ‘Chinese ancestry’ conceals bitter rivalries between the Teochew, Hokkien, Hakka and Hailamese.footnote12 The positive side of this phenomenon is that Thailand has never experienced the kind of anti-Chinese mobilizations that have characterized the modern histories of Malaysia, Vietnam, Indonesia, Burma and the Philippines. Capable, wealthy and ruthless Sino-Thais have been able to climb upwards—on condition that their ‘Chineseness’ remains very low-profile, especially under Rama IX. There are echoes here of the status enjoyed by wealthy Jews in Habsburg Vienna or Hanoverian London. In the last election, it turned out that 78 per cent of the seats in Thailand’s parliament were occupied by ethnic Chinese, even though they accounted for just 14 per cent of the population.

Against this backdrop, the question now is who will be President of the Republic of Thailand?’ Nobody will say so explicitly, but that is exactly what is in their minds. With the system of petty warlords in each of the territories, that creates frustration for everybody: they can be sure of winning in one place but not in another. The Reds can’t penetrate the territory of the Yellows, and the Yellows can’t penetrate the territory of the Reds; the south is Yellow and the north is Red. Another difficulty is that nobody can talk publicly about their Chinese identity, because it would be absurd to declare that one is Chinese but plans to be the President of the Republic. Everyone knows that they are, but it’s not considered appropriate to say so. There is no other way out, unless one of them gets killed, or something of that kind. Don’t fool yourself that the political contest in Thailand is about democracy or anything like that. It’s about whether the Teochews get to keep their top position, or whether it’s the turn of the Hakkas or the Hailamese.