To get a handle on the current position of the left, at a global level, it may be useful to start by comparing this century to the last. Epochs turn according to their own temporality, rather than following the Gregorian calendar; yet for those living them, the calendar can still provide a handy tool on which to mark historical ruptures and transitions. The 20th century was shaped and driven by two systemic dialectics, industrial capitalism and capitalist colonialism—‘dialectical’ in the sense that the development of each system served to strengthen its exploited part: here, the working classes and the colonized peoples. Dialectics is not progress by evolution, innovation and growth. It is change brought about through contradictions of the systemic dynamic, involving conflicts and the unintended consequences of the actions of systemic rulers, often at great cost; in this case including devastating wars and genocide. The crucial point of a social-systemic dialectic is that the contradictions, conflicts and human costs of suffering have a developmental tendency: in the 20th century, they brought about historic human advances in living standards, life expectancy, democracy, freedom, sex-gender emancipation and decolonization.

However, by the end of the 20th century these dialectics had stalled. The working class had advanced in the industrial societies, but finance capital was the winner of industrialization’s demise. The anti-colonial dialectic ended with the—limited and conditional, as it turned out—liberation of the colonized. Though many of its achievements persisted—labour rights, welfare states, women’s emancipation, democracy—the left of the outgoing century provided no perspective forward, no inspiration and little hope. Significantly, the neoliberal era operated as a hinge between the two centuries, not just in a chronological sense. Neoliberal-capitalist globalization put an end to the left of the 20th century; but it also generated, by its excesses, arrogance and economic crashes, a new 21st-century left. Furthermore, it became the vehicle for the rise of China and other non-Western countries, challenging the world domination of the us and thereby starting its own demise.

Instead of ushering in a post-industrial society, as dreamt by Daniel Bell—where ‘human capital’ would produce ‘enormous growth’ in ‘the non-profit area outside of business and government’footnote1—neoliberalism produced an even rawer and more ruthless type of capitalism, bent on capitalizing education, healthcare and other public services. The 21st century harbours no grand social dialectic; the new forms of financial and digital capitalism do not develop and strengthen their adversaries. They may generate well-deserved anger among their employees and even successful attempts at unionization; but the social trend of working-class employment is rather a tightening of the noose of surveillance. Outsourced industrialization will gradually invigorate an industrial working class in the Third World, but not as big a one as in Europe, nor even as in the us and Japan. National shares of manufacturing and industrial employment are already going down in Asia and Latin America and stalling at a low level in Africa.footnote2 Industrial societies shaped and driven by the class dialectic of industrial capitalism are gone forever, with the past century. The dialectic of colonialism has also run its course.

Instead of the stern but ultimately hopeful dialectic of industrial capitalism, the 21st century is burdened with its disaster-generating legacies. The effects of climate change have already become tangibly calamitous, from North America to Australia, from Central Europe to the Sahel, China, Pakistan, Sudan and Latin America: record-breaking temperatures, unprecedented drought, massive wildfires, storms, floods and landslides. The Emergency Event Database recorded 432 disastrous events in 2021, up from an annual average of 357 for 2000–20, affecting more than 100 million people.footnote3 The Cold War ended, but it soon turned out that the last Cold Warriors had left a poisonous gift to posterity. The us ‘deep state’, originally under the direction of Carter’s security adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski, followed up by the Reagan Administration, had decided to arm and finance reactionary Islamists against ‘Godless Communism’ in Afghanistan. The Islamists interpreted the collapse of the Soviet Union as their victory over one of the two non-Muslim superpowers and prepared to take down the other one. This blowback then unleashed Bush Jr’s ‘war on terror’, with devastating shock and awe inflicted across a belt of countries from Libya to Yemen, Somalia to Iraq, while cia agents kidnapped suspects and shipped them off to torture chambers helpfully provided by the new democracies of Poland, Lithuania and Romania.

A ruthless imperial geopolitics, unbound by the Cold War’s unofficial code of conduct, thus accompanied the 21st century from the start. But the contradictions of imperial geopolitics do not constitute a systemic dialectic, whereby development tends to strengthen the exploited and oppressed. Instead, the bloodshed in the ‘Middle East’ remained a sideshow to the oceanic flows of neoliberal globalization. Digital and financial capitalism are driving the dynamics of the 21st century with a technological revolution, shaking up every aspect of everyday life, from internet addiction to driverless electric cars. The speed of the high-tech companies’ surge and the scale of their world-market dominance have no precedent in world history: Microsoft’s Windows operating system drives 75 per cent of the world’s desktop computers; Facebook and its subsidiary Instagram have captured 82 per cent of the world’s social-media traffic; Google has conquered 92 per cent of the global search-engine market, and its Android operating system drives over 80 per cent of the world’s smartphones.

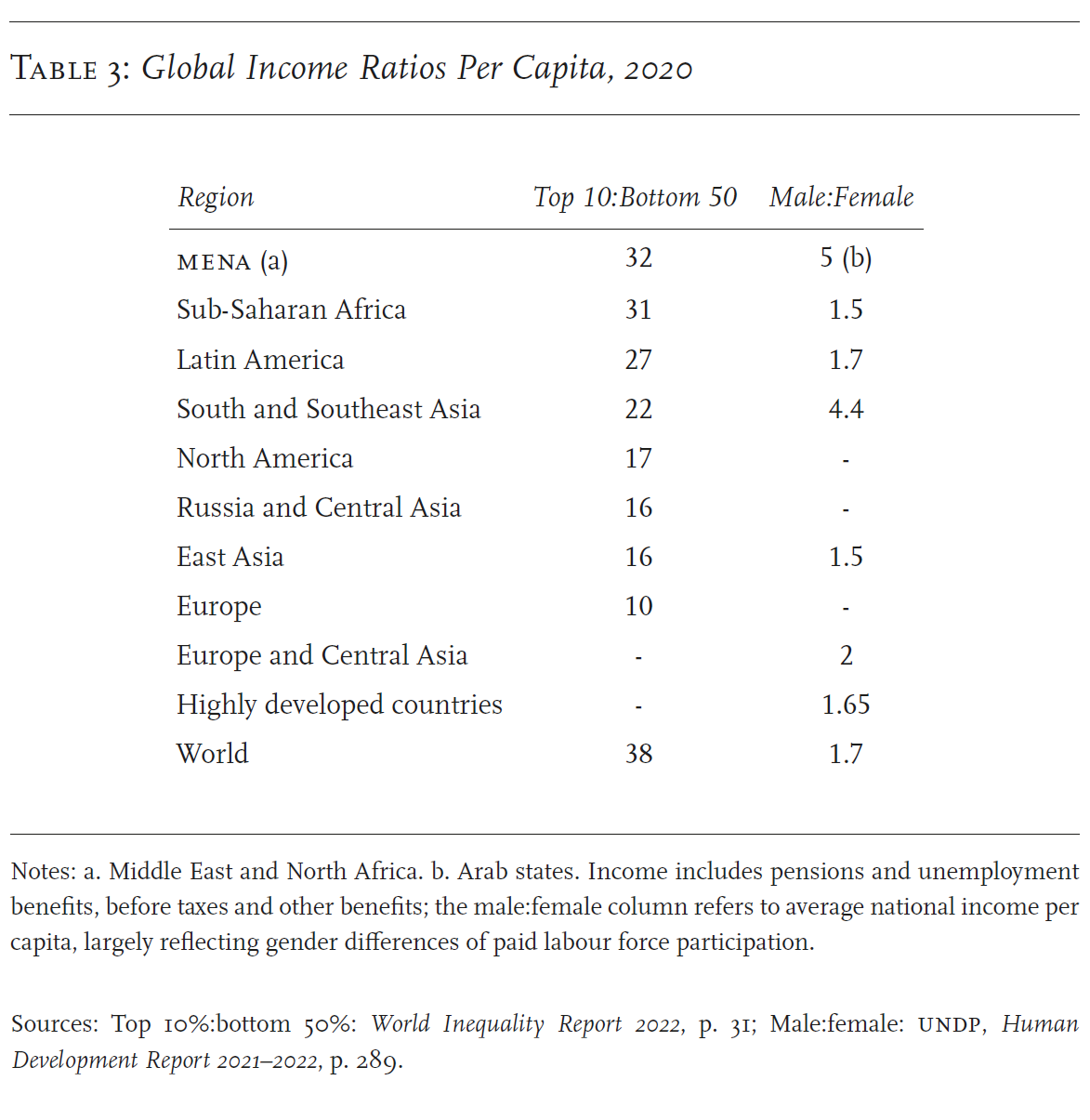

Comparable processes have taken place in finance, where a handful of ‘asset management’ firms manage the enormous capital assembled by institutions such as pension funds, and the super-rich. Only two countries, the us and China, have gdps greater than the wealth managed by BlackRock, whose assets hover around $10 trillion. The ten largest asset-management firms together control $44 trillion, which is the sum of the annual gdps of the us, China, Japan and Germany. Among the twenty largest firms, fifteen are American. The rulers and owners of these digital and financial corporations, for all their business acumen and their studiedly informal dress, are among the greediest and most ruthless capitalist classes since the age of the robber barons and slave plantations. Unanimous in denying their workers the most elementary union rights, as in their elaborate schemes of tax evasion, they milk public subsidies wherever possible. The gross profit rate, after the costs of components and manufacturing, of an iPhone or a Samsung Galaxy was over 60 per cent in the 2010s.footnote4 This is the third disaster-generating legacy bequeathed to the 21st century: galloping inequality. The ruthless new capitalism has not benefited the majority populations in the countries of the core, nor even their overall national incomes, which averaged only 1.8 per cent annual growth for 2000–19.

Nevertheless, the 21st century has produced a plethora of new lefts that have been impressively creative and radical in form, starting from their own indignation rather than from the defeats of their predecessors. This essay is an attempt to understand the context of the 21st-century left and its innovative responses to the major challenges of the present conjuncture: the looming climate catastrophe, the new world of imperial geopolitics and the abysmal economic inequalities among an increasingly interconnected humankind. What are the prospects for the 21st-century working class and for the ideas of the left? Nearly a quarter of a century ago, addressing these questions in a characteristically sharp editorial, Perry Anderson concluded that the necessary starting-point for a realistic left was ‘a lucid registration of historical defeat’. He by no means considered this final, even though he saw neoliberalism as ‘the most successful ideology in history’, under which ‘little short of a slump of inter-war proportions’ would be ‘capable of shaking the parameters of the current consensus’.footnote5 At the time, I found Anderson’s essay a model of integrity and steadfastness; I still do. But with almost twenty-five years of hindsight I also think that our 20th-century legacy needs to be pictured somewhat differently, so that we can better grasp what has happened in recent decades and what might unfold during the rest of the century—the hottest on Earth for the last 12,000 years.footnote6 In what follows, I will briefly sketch the main determinants of the 20th-century left and the ‘hinge’ of neoliberalism, before going on to examine the different contexts in which 21st-century lefts have taken root, contrast their forms and repertoires, analyse their impact and assess the challenges ahead—in Africa, Asia and Latin America, as well as the ‘Global North’. ‘The left’ here will be taken in a broad ecumenical sense, and the world as the planet.

1. the dialectical century

The world of the 20th century emerged in the 1870s, the decade that saw the industrial take-off of the post-bellum us and the unified German Reich, as well as the Berlin Conference on the colonization of Africa. Henceforth, Europe and North America would increasingly be dominated by the social system of industrial capitalism, and Africa and Asia by capitalist colonialism (Latin America, still governed by pre-industrial settler states, had neither). Capitalist colonialism differed from earlier forms of colonialism in two ways. First, colonial conquests were to be valorized or ‘developed’; they were not tributaries or slave plantations. Second, their populations were subjugated indigenous peoples; they were not meant to be colonies of settlers. The two dialectics were of course intertwined; global imperial geopolitics preceded the 20th century—indeed, one could argue that the first ‘world war’ was the 1754–63 Seven Years War, fought for imperial dominance between coalitions led by Britain and France on battlefields from Canada to Bengal. But the industrial conflicts of the 1910s and 1940s involved an unprecedented level of socio-economic mobilization, causing human slaughter on a new scale. This also meant that the outcomes of the two 20th-century world wars had enormous consequences, making them major moulders of the century.

The dialectics of industrial capitalism and capitalist colonialism were remarkably similar. Both created a new social stratum that was essential for the functioning of the system, yet at the same time was a subordinated force with an inherently rational-adversarial potential: factory workers on the one hand, and an intelligentsia of the colonized on the other—the bilingual ‘armies of clerks’ that Benedict Anderson described as essential for the administration of the colony.footnote7 Both the factories and colonial colleges brought together people from different villages, provinces or tribes, creating a common experience and identity, forged in opposition to the forces of capital or empire. Colonial education involved learning about the colonizer’s institutions—nation-state, national independence, political parties, popular representation, democracy—all of which were denied to the colonized. Systemic development involved the growth of the industrial working class and of the colonized intelligentsia, in cohesion and self-confidence as well as in numbers.

These tendencies were slow to unfold. Initially, the emergence of industrial capitalism benefited only the capitalists and the rentier bourgeoisie. Workers’ wages were stagnant or declining, while the exploitation of child labour was horrendous, as was industrial-plantation slavery. Yet one aspect of its dialectic was unprecedented economic growth under a system that came to be spearheaded by us capital. Nevertheless, it took more than a century for the Industrial Revolution to deliver aspects of its productive dynamics to the masses of the Global North, and another fifty years to reach the Global South; it was only between 1998 and 2013 that ‘extreme poverty’, as designated by the World Bank, was almost halved, declining by nearly a billion, mainly but not exclusively in China.footnote8 Yet with industrial capitalism, the working class and its movement advanced in size, strength and political influence. Trade-union and collective-bargaining rights were normalized in the advanced-capitalist world after 1945: labour representatives gained a say in government, and rights to social security, housing and workplace health and safety expanded. The third quarter of the 20th century, the culmination of industrial capitalism, was also the high point of working-class influence in the industrial welfare states. Unionization rates in the oecd peaked in the 1970s, as did the social and political weight of the working class.

The 20th century also brought major advances for women, once capitalist proletarianization had undercut the power of dispossessed fathers. From Friedrich Engels to August Bebel—whose Woman and Socialism was a bestseller second only to the Communist Manifesto—the Marxist labour movement was committed to women’s emancipation, even if it did not always live up to this in practice. Emancipation from patriarchy was a legislative priority for the Russian and Chinese Revolutions; a bold step in predominantly traditional peasant societies.footnote9 While the bourgeois norm of the housewife retained some attractions for both men and women of the working class, this began to change with the opening of mass higher education in the rich countries after 1945; the educated daughter of a working-class family now had better alternatives to housewifery than domestic service or industrial labour. Or, more precisely, she did not ‘have’ them, but she could see them and fight for them. In the sphere of politics, however, the legacy of women’s conservative subalternity persisted for longer. Guided by priests and mullahs as well as by fathers and husbands, the majority of women continued to vote for the political right down to the final decades of the 20th century; it was only in the 1990s that the ‘gender gap’ became a norm in the Global North, with women tending to be more left-of-centre than men.footnote10

Compared to the half-millennium of European colonial conquests and domination, the 20th-century processes of national liberation and decolonization were swift, condensed into some seventy years, if we omit the precursors of Haiti and the Philippines. But it was a hard and bloody battle against institutionalized racism and repression, fought by popular mass movements mobilized by the nationalist intelligentsias. Although there were a few peaceful transfers of power, all imperial states without exception resorted to war or targeted assassinations in defence of at least some parts of their dominions. National liberation in Africa and Asia was an epochal achievement, in which the lefts of the Global South played a central role, with significant support from their northern counterparts. Solidarity with anti-colonialist and anti-imperialist movements was a central principle for the 20th-century left, from the Comintern effort in 1920, the Congress of the Peoples of the East in Baku, and its crucial agents in 1920s China to the anti-Vietnam war protests and the anti-apartheid and pro-Palestinian movements.

At one level, then, this was a century of left achievements, in which the political seeds of 18th-century revolutions—French and Haitian in particular—were brought to fruition. Daring attempts at anti-capitalist revolution in Russia and China succeeded against all odds, creating mighty new societies out of decaying dynastic regimes. Decolonization succeeded worldwide; from the dreams of underground revolutionaries in the first half of the 20th century there sprang a phalanx of large, independent nation-states.footnote11 Israeli settler colonialism is now a minor aberration, rather than an example of a major European-imperial form. Of course, these achievements did not bring the realization of dreams. The industrial-class dialectic described in Capital ended as welfare states, within the confines of capitalism. Nor did the great revolutions carry their people to socialism or communism in the Marxian sense; the need to survive by developmentalism and the brutalizing consequences of the counter-revolutionary civil wars overtook the socialist project. Nor did the postcolonial states become beacons of popular freedom, justice and equality.

Yet the conviction, empirically basically correct, of the dialectical character of capitalist and colonial exploitation provided the 20th-century left, reformist as well as revolutionary, with a long-term perspective and a resilient collective self-confidence which could survive the direst of times. Being on the left meant seeing a horizon of socialism as a realistic future prospect. The revolutions of the 20th century, from Russia to Cuba, played a part in this. Assessing their consequences is beyond the scope of this essay, but their effects on the 20th-century left should nonetheless be touched upon. They could be summed up under three headings: inspiration, division and hope. The Bolshevik Revolution inspired the workers of Europe and the Americas to fight for socialism, along with intellectuals and popular leaders across Asia—from the Caucasus to China and the then Dutch East Indies. The Chinese Revolution likewise inspired peasants’ and workers’ revolutionary movements across South and Southeast Asia, while late Maoism fortified student movements and mobilizations from France and Italy to Naxalite Northeast India and Nepal. The Cuban experience helped to ignite a hemispheric anti-imperialism, turning much of Latin America into guerrilla country.

But from the beginning, these revolutions also sowed division on the left. The Russian Revolution caused a rift—alongside that created by the imperial war in 1914—between the communist cause of proletarian dictatorship and the reformism of the social-democratic tradition. Such divisions were entrenched by the repressive elements and foreign Realpolitik of the post-revolutionary states and the Cold War Atlanticism of Western social democracy. More fundamentally, however, the 20th-century revolutions remained in some sense a beacon of hope. They proved that non-capitalist societies could exist; ergo, better ones, with more freedom and equality, were possible. These hopes were not sheer illusion, as the emergence of a leader like Dubček in 1968 would demonstrate.

The militants of ’68 saw the world through the lens of revolution—and understood their setback as a failure to make a revolution, for which an insurrectionary party was required. Their model was inherited from the Leninist tradition, with its competing interpretations: Maoist, Trotskyist, several varieties of Eurocommunist, and even some fledgling attempts at urban guerrilla warfare—the Italian Red Brigades and German Red Army Faction—all of which ended in failure. In fact, the rebellious movement of ’68 and the years around it did not erupt out of the grand dialectics that shaped the 20th century. This was above all a generational cultural revolt, led by the first layers to have grown up without the shadows of poverty and scarcity, demanding and creating a new culture of freedom, defined by rock music and sexual liberation. Nevertheless, this culture did become politically explosive through its coincidence and intersections with the systemic dialectics of working-class strength and militancy—the French May ’68 included a general strike and nationwide workplace occupations—with the rise of feminism, the us colonial war in Vietnam and wars of national liberation in Africa.

While there was never really a European revolutionary situation during this period, revolution was nonetheless in the air, with us forces rattled by the Tet Offensive, the Chinese Cultural Revolution raging, guerrilla wars breaking out in Latin America and Fidel Castro asserting that ‘It is the duty of every revolutionary to make revolution’. In late May, de Gaulle even thought it necessary to visit his generals and assess their loyalty. This atmosphere persisted over the following years, with huge strike movements hitting Italy in 1969 and revolutions toppling the fascist regimes of Portugal and Greece in 1974. After the dust from ’68 had settled, it was clear that a new cultural and social situation—based on anti-authoritarianism and feminism—had emerged. But politically, the movement reached a dead end. In some respects, the eruption of ’68 was similar to the indignados of the 2010s: both were youth-led anti-authoritarian uprisings, involving experiments in participatory democracy and the occupation of streets and squares. But the unrest of the 2010s unfolded in the shadow of austerity, privatizations and rising unemployment—all largely absent in 1968—and the two had vastly different developmental trajectories. Whereas the indignados generated new political movements and parties—Syriza, Podemos, the campaigns of Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn, all of which admittedly reached their limits in the coming years—the 1968 generation produced very little in terms of new politics and was contrastingly sterile.footnote12

If industrial capitalism reached its peak in the Western core in the 1970s, its transcendence was nowhere to be seen. This developmental zenith did produce some radical and concrete proposals for socialist transformation from the mainstream labour movement, however. The boldest of these schemes came from Sweden and France, while ideas of enterprise democracy, co-determination and the humanization of work spread more broadly. ‘It must be the task of social democracy to rally people around an alternative to private capitalism and to a bureaucratic state capitalism’, wrote Olof Palme, then Prime Minister of Sweden, identifying ‘democratic socialism’ as the answer.footnote13 In 1976, the congress of the lo, the powerful Swedish trade union confederation, adopted a proposal for ‘wage-earners’ funds’, given a radical twist by the trade-union economist Rudolf Meidner. It entailed the annual allocation of corporate shares to union-controlled funds, which would gradually become majority owners of the core Swedish industries. The Social Democratic party leadership, including Palme, were taken by surprise and unhappy with the proposal; in 1978 the party accepted a watered-down version, with a stop clause preventing a majority change of ownership. A second mainstream attempt at transcending capitalism emerged in France with the Union of the Left—the socialist and communist parties, under the so-called Common Programme. Conducted by a wily politician of the Fourth Republic, François Mitterrand, without any socialist credentials hitherto, this pledged to nationalize nine major industrial groups, along with the credit and insurance sectors. The first steps in this direction produced a revolt of the markets and the policy was reversed within two years, after virulent resistance by the bourgeoisie and its media. The result was not a fight but a—staged—backdown by the mainstream left, the Eurocommunists as well as the Social Democrats. The British miners did put up a fight but were defeated.

A similar dynamic unfolded in the ussr and Eastern Europe, where social development had finally spawned a current of democratic-reformist Communism. Mikhail Gorbachev was its leading figure, but similar tendencies had come to the fore in Hungary, Poland and Slovenia, and were latent in other parts of Eastern Europe. Such movements were short-lived, despite the fact that support for the restoration of capitalism was never strong.footnote14 They were both stimulated and stymied by the impasse of social and economic development in the Soviet Bloc, after the stalling of the epic catch-up after World War Two. An explanation for this lies outside the parameters of this brief survey; but it was clearly related to the emerging post-industrial, digital productive forces, which were novel to industrial socialism, West as well as East. Soviet adaptation was moreover impeded by the huge costs sunk in military superpower competition, which grew to a third of total state expenditure.footnote15 In China, late-Maoist ventures such as the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution ended in failure and chaos, while a return to Soviet socialism held no promise. Searching for a new path, the Deng leadership invited Milton Friedman and his ilk to China, and even sent an exploratory mission to Pinochet’s Chile.footnote16 Yeltsin, meanwhile, put the Russian economy under the tutelage of Western neoliberal economists, with the cia and Saatchi & Saatchi securing his re-election in 1996. The Western overlordship of Russia in the 1990s returned the country’s relative levels of economic inequality and national income to those of Tsarist times.footnote17

Was this, à la Anderson, the defeat of the left? I would venture that, with hindsight, the end of the 20th century could more accurately be characterized as a situation of impasse and exhaustion: the impasse of the Soviet-style economies and the exhaustion of the Western labour movement, at the peak of industrial-capitalist development—or, putting these two together, the exhaustion of an industrial era of reform and revolution. The century ended with neoliberalism replacing national welfare-state Keynesianism as hegemonic socio-economic ideology. This aggressive, exclusively profit-focused and primarily financial capitalism became the new paradigm, and the slow process of (national) economic equalization since 1945 was abruptly reversed.footnote18 This was a remarkable return to power for militant right-wing liberalism, once utterly discredited for its helpless insouciance before the mass unemployment and impoverishment of the 1930s Depression. Now it was Keynesianism which stood seemingly helpless in front of the new crisis of the 1980s, and neoliberalism that appeared to offer a solution. The new left of the 21st century must be assessed against this background, as an attempt to keep socialism alive under the worldwide hegemony of neoliberalism.

2. the neoliberal interlude

Given its pivotal role in recent history, the context and contours of the resurrection and worldwide diffusion of neoliberalism should be briefly sketched. First, there was a secular decline in manufacturing employment in the us, starting from the late 1960s. This had a technological basis, but it was accelerated by the return to the world market of America’s formidable competitors, Germany and Japan—along with Japan’s uniquely industrialized former colonies, South Korea and Taiwan.footnote19 The profits of Northern industrial capital were thereby squeezed between rising global economic competition and the advance of labour. In addition, the breakdown of the post-war inter-state currency system, related to the costs of the Vietnam war, opened up space for unregulated financial operations, while the newly assertive Arab petro-states hiked the oil price to protest the us rescue of Israel during the 1973 Ramadan War. In this context, the compass of Keynesian national-welfare states could no longer provide a true north. The Phillips Curve, supposedly indicating the trade-off between unemployment and inflation, failed to work.

For capital, there were three shining paths out of the Northern profit squeeze. One was state repression: promoting and supporting union busting. The governments of Reagan and Thatcher led the way, with the former taking on the public air traffic controllers and the latter waging war against the miners. Another avenue was globalization, enabled by new digital technology which facilitated the outsourcing of manufacturing to low-wage countries. In the us, imported manufactured goods rose from 14 per cent of domestic production in 1969 to 45 per cent in 1986. Third, digital technology also opened new means of electronic financial speculation: in the us the fire sector (finance, insurance, real estate) overtook manufacturing as a share of gdp around 1990 and became the country’s primary source of profit a few years later.footnote20

On the ideological front, neoliberalism gained traction as a resourceful right-wing riposte to the cultural changes of the 1960s. In August 1971, Lewis Powell—a lawyer for the Tobacco Institute, soon to be appointed to the us Supreme Court—addressed the Chamber of Commerce and called for big business to adopt a combative stance in the culture war. Powell did not see ‘extremists of the left’ as ‘the principal source of concern’, but rather the ‘chorus of criticism’ of the American free-enterprise model, which, he said, came from ‘perfectly respectable elements of society: the college campus, the pulpit, the media, the intellectual and literary journals, arts and sciences, and politicians’. Most dangerous was Ralph Nader’s anti-corporate rhetoric and the criticism of business ‘tax incentives’. Organized labour, however, was no longer a major problem.footnote21 As we have seen, the diffusion of neoliberalism—promoted by the imf and the World Bank—culminated in the embrace of Pinochetismo by liberal economists, technocrats and politicians in the post-Soviet space and China.

Neoliberalism has shown great resilience, but after four decades its hegemony is now ending—a longer reign than Keynesianism, admittedly, but a brief spell in the long history of capitalism. Three events have been crucial. First was the financial crash in the global capitalist core in 2008. Neoliberalism was not yet finished—indeed, an acute observer like Colin Crouch could remark upon its ‘strange non-death’—but its legitimacy was severely undermined, and the austerity policies rolled out to compensate for the generous bankers’ bailouts added to the rot; indignados in many countries formed mass protest movements; rising inequality became an official concern at Davos; and ‘democratic socialism’ returned to Anglophone vocabulary. The then head of the imf concluded that the crash had ‘devastated the intellectual foundations of the last twenty-five years.’footnote22

Second, and in the long run probably more decisively, after 2010 the us political elite, supported by a substantial part of the economic establishment, discovered that China was winning at the game of capitalist globalization. Although us capital was thriving, the American nation-state was not. Politicians realized that global supremacy—and their own electoral seats—depended not only on a few big corporations, but also on the resilience of the state and its people, even on its working class. In this context, with the gap between the ultra-rich and the rest of the population still widening, distributive issues moved back up the agenda. Starting with Trump, and followed by Biden, the us government began to pivot towards a protectionist geopolitics. Third, the Covid-19 pandemic and ongoing climate disasters demonstrated the inadequacy of markets to cope with the urgent issues of the new century. The once canonical words of neoliberal statesmanship—‘Government is not the solution to our problems, government is the problem’—now sound outlandish to many ears.footnote23 Meanwhile, the new world of imperial geopolitics served to undercut such key tenets of neoliberalism as ‘globalism trumps nationalism’.footnote24 The ‘America First’ trade and economic policies of the Trump and Biden administrations have directly undermined such norms.

The state returned to the centre of capitalist economies with the bailout of 2008, and even more so during the pandemic. In 2020, general government debt in the advanced economies exceeded its level during World War Two, running at over 120 per cent of gdp. The us’s additional spending and foregone revenue was among the highest in the world, well above 10 per cent of gdp.footnote25 Neoliberalism was a specific form of ruthless capitalism, centred on the ambition for market sovereignty over the entire world. But while the triumph of imperial geopolitics over market globalization is now clear, the new phase of capitalist accumulation, no less ruthless than the last, is yet to be baptized. Descriptively, at this juncture, it is digital-tech finance capitalism, bent upon accumulation within state-defined geopolitical parameters.

3. the new century’s left

This chain of events did not unfold as a systemic dialectic—that is, as an endogenous process, deriving from the developmental logic of the social system. Industrial capitalism has mutated into a form of digital-financial capitalism which does not produce or develop its own adversaries. The bulk of the protesters against neoliberalism, for example, are not key parts of the neoliberal economy, but rather people outside it whose lives have been invaded and damaged by neoliberalism. Similarly, the rise of China was not a systemic development, but the entry of a player who turned out to be more skilful than the champion. The contradictions of imperial geopolitics do not constitute a dialectic with the capacity to strengthen the exploited and oppressed. Instead, as we have seen, the 21st century is burdened with the disaster-generating legacies of its predecessor—climate change, inequality, war—while the creative-destructive dynamics of capitalism keep rolling on. That capitalist dynamism leaves the masses in dire poverty and mainly enriches the wealthiest, while comforting a fragile middle class, should not come as a surprise. Yet any analysis that focuses solely on the supposedly lethal crises of capitalism, ignoring possible disruptive agents, is looking at the world from a windowless ideological attic. Trade unions have become more active in many countries of the South, though usually without creating large or solid organizations; even in the North they are showing new signs of militancy. By contrast to the left’s late 20th-century despondency, its early 21st-century successor has displayed a new dynamism and inventiveness, even if its power is still limited.

Ignoring the bleak old era of their mothers and fathers, the new left from around the turn of the millennium took radical politics onto a new level.footnote26 It spearheaded responses to the global dispensation of neoliberal capitalism, and to its new cycle of imperial wars. It sowed seeds of socialism, above all in Latin America. It learnt much from, and about, a new ally, free of the modernist myopia and arrogance of the old left: indigenous populations, which re-emerged as a significant force in community organizing and non-capitalist ecological initiatives, primarily in Latin America but also in India. The new left circumvented the conundrum of working-class socialism confronting financialized capitalism by appealing to ‘the people’ and to radical democracy. It contributed to a worldwide return of urban uprisings, beginning in the late 1990s; indeed, the first two decades of the new century set a historical record for social uprisings in the post-1900 era, with centres in the Arab World, Latin America and the Soviet successor states.footnote27

The 21st-century left updated and revitalized the entire radical tradition through its prescient understanding of environmentalism and its commitment to averting climate catastrophe. Theoretical investigations of exits from capitalism have continued, after the end of the classical Marxian dialectic. The new left has stepped out of the shadows of the great moulders of the 20th century, into a different historical era. We can briefly identify its novel features as it first emerged through the alter-globalization movement, the new climate protests and the resurgence of socialism in the Americas.

Alter-globo. It was the ever-faster capitalist merry-go-round of neoliberal globalization—which reached top speed in the decade spanning the late 1990s to 2008—that helped to generate a new global left. In late November 1999, the Ministerial Conference of the World Trade Organization in Seattle became the target of a militant demonstration against the global offensive of capital. The afl-cio formed part of the opposition, leading a peaceful and nondisruptive march; but a younger cohort of radicals—students, anarchists, citizens of the developing world—managed to halt the opening ceremony, and violent battles ensued with the city’s equally militant and better-equipped police force. In June 2001, when the G8 summit gathered in Genoa—the G7 plus Russia, which had recently been admitted as a consolation for the eastern expansion of nato—it too was greeted by 200,000 angry demonstrators, to whom the security services meted out ferocious repression. In February 2003, one of the largest protests in world history took place against the us-led invasion of Iraq. Of course, it was in vain: capitalist globalization proceeded for another decade; Iraq was bombed, invaded and destroyed, albeit without becoming a Little America on the Tigris. Yet these mass demonstrations showed that another form of globalization—distinct from that of corporate outsourcing and financial speculation—was possible: global solidarity and international peace movements. These will be much needed in the coming century.

The alter-globalists also made a creative intervention in left politics: the World Social Forum, conceived as an alternative to the World Economic Forum in Davos, and intended to create a pluralistic meeting-place for all non-violent left currents who are ‘opposed to neoliberalism and to domination of the world by capital, and any form of imperialism, and are committed to building a planetary society centred around the human person’. The founders were two Brazilian activists from outside the traditional left: Chico Whitaker, then executive secretary of the Brazilian Catholic Church’s Commission of Justice and Peace, and Oded Grajew, an industrialist leading the Ethos Institute for Business and Social Responsibility, who were in turn inspired by an editor of Le Monde Diplomatique. The first wsf was held in Porto Alegre in 2001, with support from the local Workers’ Party government, and since then it has met in places as diverse as Mumbai, Nairobi, Caracas, Tunis, Montreal and Mexico City, while inspiring other regional fora in Europe. It has twice drawn more than 150,000 participants, with a unique social and cultural range, from the left intelligentsia to trade unionists, indigenous movements from several continents, the peasant Via Campesina movement, organizations of slum-dwellers, feminists, human rights activists, environmentalists and so on. The wsf still takes place annually, although the number of participants has declined. From early on there were tensions between two distinct visions for the Forum: as a meeting-place where participants could exchange ideas and experiences, or as a movement capable of making concrete demands and calls for action. Both sides of this debate have acknowledged the need for a broad global movement, but its founders are anxious not to risk the unity and diversity of the Forum by adopting policy positions. One way or another, the wsf will need some kind of renovation if it is to recapture its original vitality.

Climate protests. Environmental concerns began to grow as the industrial era reached its peak in the 1960s and 70s, with alarm bells sounded by Barry Commoner, Rachel Carson and the Limits to Growth report, compiled by mit’s Sloan School of Management and published by the Club of Rome. Green parties began to spring up in Western Europe, New Zealand and Tasmania, many of them originally identified with the left; but given their distinctively middle-class base, there was always a tendency to move toward the political centre (hence the German Greens’ coalitions with both the Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats). Confronted with the enormous challenges of the climate crisis, however, most Green politics has become a variant of politics as usual. Climate change emerged as a topic in international scientific organizations in the 1980s, before becoming an explicit issue for un member states in 1990. This previously elite concern became a mass one in the mid-2000s, with a strong left current apparent at least since the advent of the Global Justice Now Network in 2007, which connected climate crises to capitalism. Meanwhile climate-change concern has become mainstream and its dismissal a defining feature of the extreme right. It is a molecular movement of many currents, although not entirely free of the factionalist venom that plagued the 20th-century left.

The climate movement has generated the fastest-growing social movement in history, Fridays for Future, founded by Greta Thunberg, a fifteen-year-old schoolgirl who, on 20 August 2018, skipped school and sat down outside the Swedish Parliament building with a placard, some fliers and her smartphone, on which she informed the world via Instagram and Twitter about what she was doing. In 2019 she became the most iconic living social activist, accepting invitations to address the un General Assembly, uk Parliament, French National Assembly and Davos, while inspiring an expanding global movement. The stated goal of Fridays for Future may appear modest, and not specifically left-wing: ‘to put moral pressure on policymakers, to make them listen to the scientists, and then take forceful action to limit global warming.’ Yet, besides ‘Keep the global temperature rise below 1.5 C’ and ‘Listen to the best united science’, its list of demands includes ‘Ensure climate justice and equity’, although this has not yet been given any concrete form. Thunberg has a good sense of both global history and contemporary class relations: ‘We will not allow the industrialized countries to duck responsibility for the suffering of children in other parts of the world’; ‘We are about to sacrifice our civilization for the opportunity of a very small number of people to make enormous amounts of money . . . it is the sufferings of the many which pay for the luxuries of the few.’footnote28

The mobilization of the world’s youth by Fridays for Future has been phenomenal. According to its own reporting, it has assembled 17 million strikers in 8,600 locations,footnote29 though the real figure is presumably somewhat smaller, as many have participated more than once. The largest movements have been in Germany (3,772,071 participants), Italy (1,687,554), France (1,450,105) and Canada (1,137, 803). More than 100,000 participants were also registered in Australia, Austria, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland and the uk. Numbers are heavily concentrated in Western Europe and Britain’s former white dominions, but 30,476 took part in Poland, 26,515 in Chile, 13,017 in India, and 8,060 in South Africa. There were also 90 participants in Burkina Faso, 5 in Burundi, 1,946 in Kenya, 15,000 in Peru, 156 in Thailand, 1,000 in China, 2,000 in Iran, 2 in Saudi Arabia, and 1 in Vietnam. After its annus mirabilis of 2019, however, the dynamism of Fridays for Future was interrupted by the pandemic; the extent to which it can be recaptured remains to be seen.

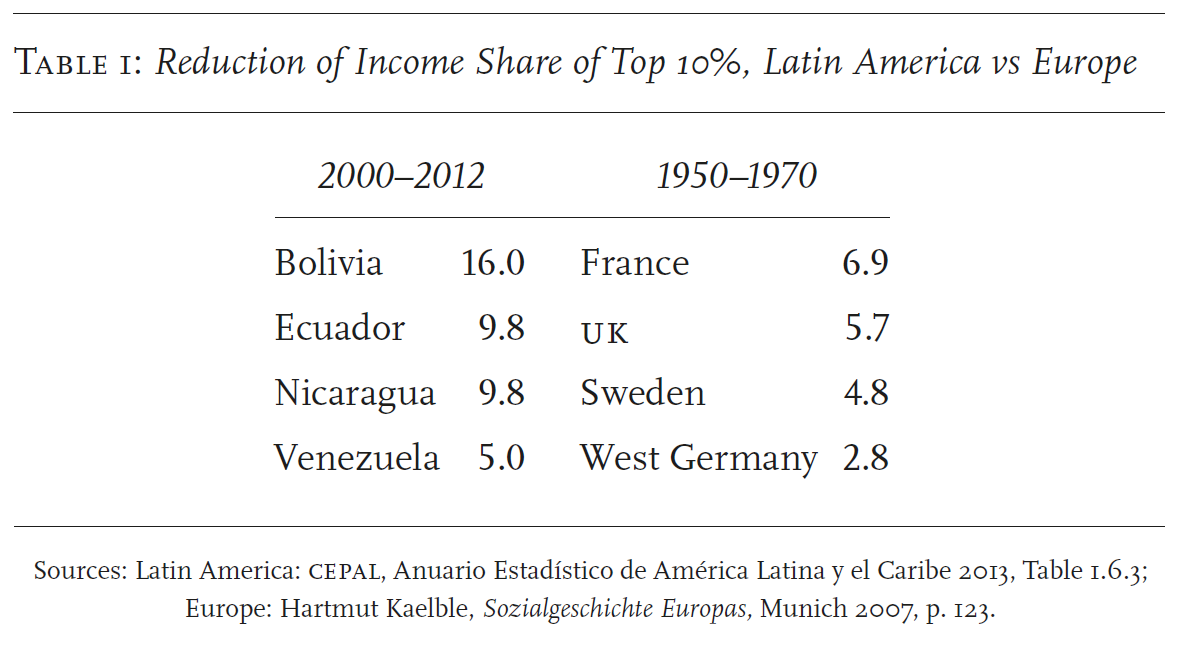

New World socialisms. Within a decade of the implosion of the Soviet Union, new sprouts of socialism were appearing in Latin America, amid waves of popular protest against actually existing capitalism. Hugo Chávez was elected in 1998, Lula in 2002. In 2005, Evo Morales won a decisive majority in the Bolivian elections, running on an explicitly socialist platform. Soon after, Venezuela re-elected Chávez against a united opposition with a resounding 63 per cent of the vote, while Rafael Correa, an outspoken advocate of ‘21st-century socialism’, received a significant presidential mandate in Ecuador. The context for these breakthroughs was a prolonged economic crisis stretching back to the 1980s, caused by falling export-commodity prices and high interest on foreign debt, thanks to the us Federal Reserve, topped by imf-decreed austerity measures that hit the popular classes. The political system in these countries had all but collapsed after the establishment parties chose to represent the imf rather than their own citizens. Venezuela’s dominant parties fell apart, with the centre-left Acción Democrática utterly discredited after its last president allowed the army to massacre protesters in Caracas in 1989. Argentina, meanwhile, suffered a dramatic economic collapse which prompted the sitting president to flee by helicopter, but the durable and multifaceted Peronist tradition survived, and was revitalized by an outsider from within the tradition, the Patagonian governor Néstor Kirchner. The achievements of these socialist governments were modest but not insignificant (Table 1). Rising commodity-export earnings were used for infrastructure spending, social programmes and poverty reduction, on a scale that was large by regional standards. Bolivia was most successful, implementing extraordinary wealth redistribution measures while largely maintaining economic growth above 4 per cent from Morales’s election in 2006 until the pandemic.

Since Chávez’s death in 2013 and the crash-landing of the Venezuelan petro-economy, as the oil price fell from $120 in mid-2014 to $30 at the end of 2015, with us sanctions battening on trade, the former President has been used as a scarecrow-like figure to frighten wavering voters in Latin America and beyond. Yet Venezuela’s economic disaster was a post-Chávez phenomenon. When he was first elected in 1998, Venezuela’s gdp per capita was 72 per cent of Mexico’s; by 2013, it was 116 per cent. For all his narcissistic flaws and autocratic tendencies, Chávez was both a popular politician and an innovative statesman: a ‘larger-than-life’ (as the ambiguous expression goes) figure of the early 21st-century left. As an admirer of Bolívar, he was also a passionate Latin-Americanist who was perhaps best known for alba, his ‘Bolivarian alternative’ to the us-dominated Free Trade Area, while his Petrocaribe alliance provided subsidized oil to Caribbean countries. His celac project, the intergovernmental Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, launched in 2010, managed to bring together a remarkable troika of Latin American leaders: the right-wing Sebastián Piñera and Chávez himself preparing for their successor, Raúl Castro.

Latin America’s ‘21st-century socialism’ was not the beginning of the end of capitalism. But it contributed new ideas and practices to the struggle, including Chávez’s local-democratic projects, in which communities were able to elect their own councils, which remained fully accountable to the local people. They in turn formed communes that worked to develop cooperative production and services, creating common goods and use-values. To gain government recognition and access to specially designated public funds, the communes would have to commit to building socialism. In 2013, an official census listed 1,400 such communes, although the majority were still ‘under construction’. The communal project was imposed from above, in a legally dubious manner—based on a draft constitutional amendment that had been narrowly defeated in a previous referendum. It was not organically linked to the spontaneous surge of local community organizing during Chávez’s first presidential term. But stripped of its partisan and instrumentalist features, the project was an innovative contribution to socialism. The communes were part of a larger programme to create a parallel socialist power and state. Under Chávez, expansive educational, social and healthcare policies were entrusted to extra-bureaucratic ‘missions’, staffed largely by Cubans—considered more committed than the privileged professionals of the rentier-state. After the failed anti-Chavista coup of 2002, the army and the other repressive forces were successfully purged, enabling them to withstand the frantic attempts of the Venezuelan bourgeoisie and their us patrons to incite a new military putsch.

Morales and his cohort preferred ‘communitarian socialism’ to ‘socialism of the 21st century’. In Bolivia, ‘community’ is replete with concrete cultural meaning. The Bolivian socialists have been working on the question which absorbed Marx’s final years: is there anything of value to socialism in pre-capitalist communities and cultures? Their answer is yes. Their ‘community socialism’ is rooted in the indigenous Andean ayllu. As the current Bolivian vice-president David Choquehuanca noted, ‘We have always governed ourselves in our communities. This is why we maintain our customs, perform our own music, speak our own Aymara language. This is why we are incorporating into socialism something that it has resisted for 500 years—the communitarian element.’ He went on to link this to modern forms of social organization: ‘In Bolivia there must be around ten thousand communities, and in each community there is a union of campesino workers.’footnote30

The early 21st-century Andean left grafted interpretations and elaborations of ancient Indian concepts onto the modern tree of socialism, as part of a civilizational critique of—and alternative to—capitalism. Aymara notions of suma qamaña, roughly translated into Spanish as bien vivir or ‘living well’, were integrated into the new constitutions and development plans of Bolivia and Ecuador. Their core concepts were respect for nature and Pachamama, or Mother Earth, plus collective ownership of natural resources, social reciprocity and solidarity. In one influential Bolivian interpretation, bien vivir was contrasted with the creed of vivir mejor, ‘better-off living’, associated with egoism, individualism and profiteering.footnote31 One might see the former notion as pre- or post-modern and the latter as typically modern. These new additions to socialist discourse responded to a strong Indian cultural renaissance in the Andean regions and more generally to the worldwide re-emergence of demand-making indigenous populations. This was prefigured by the Zapatista movement in southern Mexico, a vindication of indigenous America launched simultaneously with the us-imposed nafta deal. But though the Morales and Correa governments were undoubtedly serious in their respect for Mother Earth, they were not persuaded by Northern ideas of degrowth and were committed to the economic development of their poor countries, which largely depended on the extraction of oil, gas and other mineral resources. This led to serious conflicts, not only with the bourgeois opposition but also within the heterogenous governing coalitions and with some indigenous communities in particular.

Finally, over a century after Werner Sombart tried to explain Why There Is No Socialism in the United States (1906), a would-be presidential candidate, Bernie Sanders, raised the banner of ‘democratic socialism’ in the us and won more than 13 million votes. That year, a Gallup poll found that a majority of Americans under thirty had a favourable view of socialism, and the Democratic Socialists of America were suddenly flooded with members. In 2019, a young strategist of us socialism, Bhaskar Sunkara, published The Socialist Manifesto, and the veteran sociologist Erik Olin Wright’s How to Be an Anti-Capitalist in the 21st Century appeared posthumously. The cutting edge of popular socialist theory had moved to North America.

4. new kinds of politics

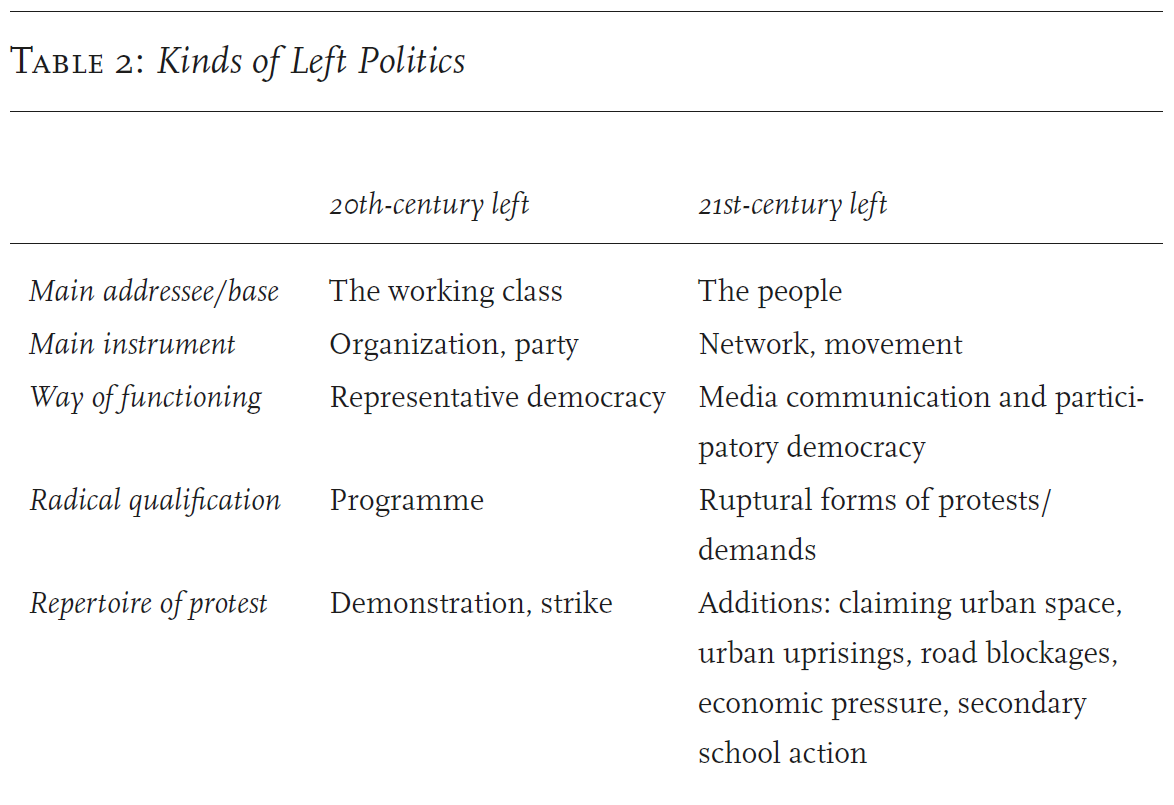

The 21st-century left has developed a new form of political practice. To capture this innovation we may start with a simple set of binaries, contrasting these novelties to the last century’s practices (Table 2, below), and then look at the fortunes of social democracy in this period. Each of the categories—social base, instruments, mode, strategy, repertoire—calls for some explication and qualification.

Social base. 20th-century socialism was a working-class movement. The deindustrialization of the old centres of capitalism, and the limited expansion of the industrial working class in the Global South have emptied the classical-Marxist political perspective of its original meaning.footnote32 In its place, the 21st-century left often speaks of the ‘99 per cent’ or, in more theoretically elaborated form, ‘the people’, in contrast to the elite class of privilege and power. ‘The people’ is a classical concept in European social thought, going back to the plebs of the Roman Republic. It was revived in the 19th century by the Russian Narodniki and American Populists, and brought into post-Marxian theory by Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe.footnote33 To defenders of the status quo, ‘populism’ is always a pejorative, of course. In the left idiom, however, ‘the people’ has a clear if contestable class meaning, best expressed in the Romance languages—the French classes populaires, for example. But ‘the people’ are also gendered and often multi-ethnic. The preamble to the draft Chilean constitution proposed by the 2022 Constitutional Convention began: Nosotras y nosotros, el pueblo de Chile, conformado por diversas naciones . . .footnote34 The gendering of the people is important to the 21st-century left not only as a discursive or political matter, but as its social base. The long-term—if shifting—commitment of the left to women’s emancipation has finally been rewarded with a widespread tendency for women to be more left-wing than men.footnote35 Included in the plurinational conception of the people was also a belated recognition and rehabilitation of indigenous peoples, who have played an important role in the struggles over Chilean forests.

Instruments. ‘Organize!’ was a persistent refrain of working-class activists and in English, ‘organized labour’ has a distinct sociological and political meaning. Collective organization, solidarity and discipline are the only resources workers can mobilize against capital, the media and the police. Traditionally, working-class political power was thought to require a strong working-class party. On that point there was full agreement between social democrats and communists. Collective organizing is more difficult in the post-industrial era, but in the digital century its premises are different. ‘Connect!’ can be enough to rally masses of people. The 20th-century distinction between party, strategic base and social movement has been blurred or transcended. Podemos, La France Insoumise and Cinque Stelle not only started as protest movements but retained their loose, ‘networked’ structure as electoral parties, with weak territorial roots and internet-based voting procedures, and without clear boundaries between members and non-members. Pablo Iglesias’s successor as the standard bearer of the Spanish Left, Yolanda Díaz, the popular Communist Minister of Labour, is currently trying to unify and revitalize the left by launching a campaign called Sumar (or ‘Summing Up’). The briefly successful left-entryism into the British Labour Party and us Democrats in support of Corbyn and Sanders was also an expression of this new movementality in left party politics. Yet implicit in this post-organization politics is the sense that state power is still far off, in marked contrast to the movement-politics of 1968. The Corbynista surge election in 2017 was also the first British election in modern times when more workers voted Conservative than Labour, by 9 percentage points. In the Brexit election of 2019, this Tory advantage rose to 21 points.footnote36

Modes. Democracy—suffrage, elections, accountable governments—was a primary short-term goal of the older working-class movement, from the Chartists onwards. The struggle was most often focused on the universal right to vote, for which the Belgian labour movement staged four general strikes and Swedish Social Democracy one, all defeated in the first instance, like the Chartists, but laying the foundation for future victories. The complexity of the obstacles to popular rule first became evident in the French 1848 election, the first in the world with general male suffrage and mass participation. Voters lined up after Mass and marched to the polling booths, led by a local priest, the mayor, a justice of the peace or a commander of the national guard. A few urban workers were elected, but not a single peasant.footnote37 A critique of actually-existing ‘bourgeois democracy’ remained a staple of Marxist political theory—recently corroborated by meticulous empirical research from political scientistsfootnote38—and democratic deficits under the neoliberal dispensation became a target of wider left critiques.footnote39

The 21st-century left sets out from a much more unqualified embrace of democracy tout court. Pablo Iglesias summed up his political vision thus: ‘In short, we want a society that is equal to providing the material bases for dignity and happiness. These modest objectives, that seem so radical today, are what democracy is all about.’footnote40 This clearly corresponded to the main slogans of the Spanish Indignados in the streets and squares: ‘Real Democracy Now!’. The founders of Podemos also had first-hand experience of the Latin American left, primarily in Ecuador and Bolivia, whose experience of the 20th century had given them hard lessons in the distinction between bourgeois democracy and bourgeois dictatorship. The new movements of this century have embraced a deliberative, participatory (if mainly digital) democracy, usually rejecting structures of representation and leadership, and often frustrating official attempts at negotiation and co-optation.footnote41 On the level of political theory, Laclau and Mouffe go further, proposing to supplant socialism with a ‘radical and plural democracy’.footnote42 In some of its iterations, radical democracy is more focused on majority rule than minority rights, mass participation over pluralist opinion.footnote43 In this regard, Chávez drew another illuminating distinction:

It is not the same thing to talk about a democratic revolution and a revolutionary democracy. The first concept has a bridle, like a horse: revolutionary, but democratic. It is a conservative bridle. The other concept is liberating, it is like a discharge [disparo], like a horse without a bridle: revolutionary democracy, democracy for the revolution.footnote44

Strategy. The 20th-century left was programmatic and strategic. It had an explicit goal, a socialist or communist society, and a clear strategy to achieve it, typically set out in its ‘road to socialism’ party programme. The outlook of the 21st-century left is more modest. Iglesias put it bluntly in 2014: ‘a socialist strategy . . . poses immense problems in the practical political sense . . . we are not opposing a strategy for a transition to socialism, but we are more modest and adopting a neo-Keynesian approach’. In his 2022 election manifesto, Jean-Luc Mélenchon defined his project as ‘building a society of mutual aid, aiming at harmony among humans and with nature’.footnote45 This step back to social-liberal economics and hazy Elysian fields is clearly a recognition of the defeats and exhaustion of the 20th century. However, it is not an acceptance of subalternity to the capitalist order—a new left Bad Godesberg, formalizing German Social Democracy’s surrender to the market. The 21st-century left bases its radicalism on a ruptural opposition to the present, rather than a long-term goal or roadmap for the future. It refuses to accept the conventions of the ruling caste, and remains unbowed—insoumise—before the juggernaut of neoliberal economics.

Repertoire. The repertoire of left politics has expanded beyond the traditions of electoral politics and mass demonstrations. The Arab Spring of 2011 inspired broad movements laying claim to public urban space, establishing acampadas, or urban camp sites, from Tahrir Square via Madrid and Barcelona to Zuccotti Park. Indigenous movements in the Andes have added road blocks, also taken up by Argentinian piqueteros, the French gilets jaunes and Punjabi farmers. Consumer boycotts of Third World exploiters and campaigns for fossil-fuel divestment have continued the practices of the late 20th-century anti-apartheid movement. Mobilizations of secondary-school students are another new phenomenon. As a form of mass protest movement they emerged in Chile in the early 2000s, fighting against the capitalization of education. This subsequently developed into a broader movement of university students, one of whom, Gabriel Boric, was elected President in December 2021. In the climate movement, school pupils and their Fridays for Future demonstrations have become, at least for a time, the global vanguard.

Urban uprisings, challenging and sometimes toppling governments, have also become part of the repertoire of left politics in the 21st century. This started in Buenos Aires in 2001, where they forced the liberal president to be airlifted out, and continued in La Paz in 2003. Tunis and Cairo kicked out their dictators in 2011, Khartoum theirs in 2018, and in 2022 Colombo protesters ejected the Rajapaksa clan from office. The Red Shirts’ Bangkok uprising of 2010 failed, but nonetheless constituted a serious challenge that was met with lethal repression. In 2019, Santiago de Chile was on the verge of a civil uprising; the conservative president called it a ‘war’ and brought in the military. The authoritarian regime in Algeria also faced a serious challenge that same year from the Hirak movement, which ended the mummified incumbency of President Bouteflika, but not the regime itself. Such uprisings must be distinguished from revolutions,footnote46 in that there was no strategic nor organizational plan for taking power. These were protest movements which sought to get rid of policies and politicians, but offered no alternative programme for government. The Buenos Aires demonstrators could demand that ‘Que se vayan todos!’—‘They should all go!’—but the question ‘Then what?’ was left unanswered. The most violent uprising, in Bolivia in 2003, where Aymara peasants, miners, street vendors and students ousted the neoliberal president in protest against his mishandling of the country’s new gas wealth, ended with his flight to Miami—at which point the victorious protesters simply went home. A two-year interregnum under the vice-president followed; after his forced resignation, elections were called and Evo Morales elected. Sometimes the vacuum was filled by organized political forces, as in Argentina with the Peronist left; on other occasions it was filled by previously underground groups, as in Egypt with the Muslim Brotherhood; on others by a recycled establishment, as in contemporary Algeria and in Sri Lanka. In each instance, the left’s great lacuna was a vision of transformative power or a strategy for winning it. That is perhaps the most important difference with the 20th-century left, reformist as well as revolutionary. Even the exceptions who did think about such matters arrived at them haphazardly. Chávez’s concern with socialism came only after he was elected to office; Morales and the mas were lucky that the 2003 uprising opened up a democratic space that they would fill after the elections two years later.

Fall and rise of social democracy. Finally, no serious discussion of the left can ignore the fortunes of social democracy. Above we noted how the twinned crises of Northern industrial capitalism and welfare-state social democracy ended in the triumph of neoliberal globalization. Yet social-democratic parties made a remarkable accommodation to neoliberalism when they returned to office in the late 1990s and early 2000s. This was the era of the ‘Third Way’, the new middle-class social-democratic adaptation to post-industrial capitalism, offering neoliberalism ‘with a human face’. After a little more than a decade, this episode was over. Since then, Central-Eastern European social democracy has been marginalized, except in Albania and North Macedonia, and most of the Western variants have entered a troubled period. In Eastern Europe, in line with Third Way commitments, the social-democratic parties’ main contribution from the 1990s was to facilitate their country’s accession to nato and the eu. Third Way thinkers also inculcated the view that welfare states were ‘essentially undemocratic’ institutions, guided by a misplaced ‘obsession with inequality’.footnote47 Socio-economic achievements were minor, and widely perceived as negative. The upshot was that social concerns were successfully taken up by the national-conservative right, most effectively in Hungary and Poland. The imbalance between foreign and domestic commitments has cost the cee social democrats dearly. Many of their standard-bearers have also been involved in corruption scandals at the highest levels. The proportional electoral system still holds out possibilities of ministerial posts for some Eastern social-democratic parties, but their historic opportunity to enact social reform and welfare-state building has been lost, in large part due to their Western mentors.

The main Western social-democratic parties have mostly remained significant forces, even where they squandered their 20th-century electoral advances. They are currently leading governing coalitions in Germany and in three Nordic countries (four until the September 2022 elections in Sweden). In multi-party parliamentary systems, a 20–30 per cent vote share for a social-democratic party can give it a pivotal position in coalition politics. However, Western social democracy is not immune to marginalization or even outright extinction. The Italian psi has virtually passed away; the French ps is dying, after winning only 1.75 per cent of the vote in the 2022 presidential election (though it may yet be reborn in some form); the Greek pasok was routed and is now hiding under another name; the Dutch Labour Party has been overtaken by the left. Anglo-Labourism perdures and, under the Westminster party system, will eventually benefit from ‘Buggins’s turn’. The Socialist International is still in existence with 81 affiliated parties, despite its 2013 split when its historic core—the German spd, the Nordic and Dutch parties and New Labour—seceded to form a Progressive Alliance, courting us Democrats and Canadian Liberals.footnote48

More interestingly, ‘social democracy’ roughly sums up the social content of the protests and movement-politics of the 21st-century left. Their social demands have included public health, free public education, civic social services and democratic rights—that is, classic social-democratic priorities, to which identity rights and environmentalism have been added. The anti-austerity movements of the 2010s, from Greece and Spain to the uk and us, protested against the dismantling of social-democratic infrastructure. Iglesias rightly remarked that the aims of his party ‘would have been unremarkable for any social-democratic grouping thirty or forty years ago.’footnote49 The 2022 electoral programme of La France Insoumise, L’Avenir en commun, is more radical, surpassing the social democracy even of the 1960s, but its cooperativist aims are carefully worded to avoid any reference to socialism.footnote50

Two other social-democratic approaches can be identified on today’s left. One is represented by the new leader of the Swedish Left Party, Nooshi Dadgostar, born in Sweden to progressive Iranian refugee parents, who has concentrated her energies on claiming the legacy of post-World War Two Swedish social democracy for her party, while distancing herself from its Communist roots. Although her ideological formation took place in the party’s radical youth wing, she now appears to have been social-democratized to the point of entirely forgetting this. When asked during a tv interview about her party’s stated commitment to a ‘classless society’ and the ‘abolition of capitalism’, she was left completely speechless, and seemingly incapable of clarifying the distinction between Marxian and Stalinist conceptions of communism. Instead, she dodged the question and reiterated her commitment to the welfare state and human rights.footnote51

The Danish red–green Unity List, which brings together various remnants of the 20th-century far left, has a very different relationship to classical social democracy. The Unity List gained some salience during the 2010s, amid a highly fragmented party system. Its support hovers around 6–7 per cent nationally, but it was the largest party in Copenhagen in the latest municipal elections, winning almost 20 per cent. Its main thinker, the former mp Pelle Dragsted, published Nordisk socialism last year, which argues that the Unity List is the rightful heir to Nordic social democracy and outlines a list of concrete ‘structural reforms’ which would put the country ‘on the road to democratic Nordic socialism’.footnote52 Dragsted’s proposals compare well with Mélenchon’s L’Avenir en commun, and arguably have more political coherence.

The social-democratization of the 21st-century left thus takes different forms, with distinct ideological influences. Iglesias and Mélenchon are tactical strategists with a Marxist education, seeking new ways to intervene in an ossified political landscape, with some success. Their ruptural strategy is typical of the 21st century’s new kind of politics, and different from that of classical social democracy, even if it shares some of its programmatic content; whereas the Unity List and Left Party are both mutations of traditional 20th-century parties. Moreover, the examples of Dragsted and Dadgostar point in opposite directions—towards an innovative way out of the present system, and a defensive accommodation to it. Just as the 1968 generation fell back on the traditions of communist organizing, the 2010 protesters sought answers in social-democratic policy. The outcome of the former was clearly negative; that of the latter is as yet undecided.

5. balance sheet and challenges

We are now at the end of the beginning of the 21st century, just reaching its first quarter. What preliminary balance sheet of the new left can be drawn? We have witnessed its response to the wave of capitalist globalization that was initiated around 1980 and is now coming to an end. In innovative forms, the new left has updated the legacy of the 20th century and broken new ground, outlasting the death of grand dialectics and the defeat of the great revolutions. It has brought questions of inequality and prospects of popular rebellion into mainstream economics and political science, and onto the agenda of the bosses at Davos. It has channelled new resources to Brazil’s poor and begun to reduce inequality across Latin America. It has translated its demands for climate action into pledges from global politicians. The Arab Spring toppled two dictators and inspired the transatlantic Occupy movement. The early 21st-century left has also opened up the field for newly radicalized generations to emerge, and returned ‘democratic socialism’ to the Western lexicon. It has broadened the ideological parameters in a number of countries and laid the foundations for progressive politics, opening up discussions on the meaning of socialism and prospects for overcoming capitalism—although discussion of that must wait for another day.

However, most of the examples above are from Western Europe and the Americas. Despite the temporary importance of the Arab Spring, the 21st century has not started well for the Afro-Asian left. The fall of the murderous Suharto regime in Indonesia in 1998 created a political opening but hardly for the left, and the economy continued to move in an inegalitarian direction, although less starkly than in India, Thailand or the Philippines. Attempts at forming or regrouping labour parties in Nigeria, Indonesia, South Africa and South Korea have so far failed. The ‘old lefts’ of India and Japan, both Communists and Social Democrats, have been further weakened, and not much of a new left, even in a very broad sense, has emerged. But there is social resistance, occasionally on a large scale, as in India and Indonesia, and there have been some inspiring developments, such as the rise of a new generation of student militancy in Thailand, and Delhi’s remarkable class-alliance politics.footnote53

A survivor of the 1968 generation should greet the 21st-century left with respect. At the same time, we need to acknowledge that it is a long way from succeeding in its objectives. It proved tragically unable to stop the ‘war on terror’ and the devastation it inflicted across West Asia and Northern Africa—killing 800,000 people, 335,000 of whom were civilians, without counting Somalia and the Sahel.footnote54 During the 20th century, the left helped to create at least three enduring revolutionary states, China, Vietnam and Cuba, as well as a post-racist democratic South Africa and scores of decolonized nations and reformist welfare states. So far, the 21st-century left has few viable institutional achievements—the communitarian Plurinational State of Bolivia is the most significant exception—although the century still has a long way to run.

Furthermore, the new left’s reconfiguration of the North Atlantic political landscape looks more limited and tenuous than that precipitated by the rise of popular nationalism and xenophobia. Trump and Trumpism conquered much of the Republican party, while the dsa remains a minority current among the Democrats; Brexit stopped the Labour left and galvanized the Tory right. Once-marginal far-right parties have become respectable bourgeois-governmental partners in Spain, Italy and the Nordic countries; and respectable, if not governmental, in France. In the South, the stalling of industrial employment and growing numbers of politically volatile unemployed youth have coincided with a resurgence of religion in the form of reactionary militant fundamentalisms: Evangelical Christian in Brazil, Hindutva in India, Islamist in the Muslim world.

The simultaneity of three contextual factors seems to have been in play here. One is deindustrialization, with its unemployment, downward mobility, dislocations and the peripheralization of working-class heartlands, all reinforced by the reigning neoliberalism. Second, large-scale immigration to the us, driven by the socio-economic crises in Latin America, and to Europe, driven by the increasing poverty gap with a better-connected Africa and the us-led devastation of its Western and Northern regions. These socio-economic and cultural upheavals created large pools of popular resentment. Third, they unfurled at the same time as the weakening or abandonment of the left and centre left, as working-class social-democratic and communist parties were eroding from deindustrialization and the implosion of the Soviet Bloc. The wounded peripheries, the ‘losers’ of globalization, were abandoned by the Third Way—but also neglected by much of the 21st-century new left, urban and educated, ‘alter-’ rather than anti-globalist. A new, politically vacant social space had opened up; it was occupied by skilful political entrepreneurs with a far-right message. A formidable right-wing bloc has been formed through the rapprochement of these new players and the traditional bourgeois parties. In the Global North, this was the sombre end of a bright beginning.

Looking forward, humanity will face three main challenges in the remainder of this century. First there is the question of the habitability of the planet, as the fragile hopes of the cop26 conference have been overshadowed by the Ukraine war and its ramifications. Second, the new imperial geopolitics bring the risk of world war, taking us back to the summer of 1914. The stakes are world domination: will the white European-descended dynasty be able to maintain the pre-eminent position it has held for more than half a millennium, given the rising economic weight of Asia? Third, there is the sad legacy of neoliberal globalization, whose abysmal inequalities are still denying technological and medical advances to the majority of the human population. (Artificial intelligence and automation may also cause major upheavals, but there is little reliable knowledge about what this might look like.) How the new left will confront these three challenges is impossible to predict at present, but the prospects are not so good.

Climate crisis. In the broad climate movement there is a conviction that avoidance of planetary catastrophe will have to involve a profound societal transformation, away from a world based on private accumulation and towards a politics of care, solidarity and equality. This is also the understanding of climate scientists—as an ipcc Working Group put it in 2021 (in a statement that was subsequently deleted by the Panel’s political supervisors), ‘We need transformational change operating on processes and behaviours at all levels: individual, communities, business, institutions and governments. We must redefine our way of life and consumption.’footnote55 What that transformation would look like is a topic of lively and inventive discussion on the 21st-century left—not least between its reformist pole, which has coalesced around the idea of a Green New Deal, and an eco-socialist one aiming at transcending capitalism. That debate needs to be widened and deepened, taking into account contemporary relations of power and how to change them.

There are at least four major perspectives on climate change, which could be summarized as follows. One is civilizational and anti-capitalist, resting on a critique of modern capitalism which has produced the climate crisis through its ruthless dynamics of accumulation and consumption and its destructive disrespect for nature. This view drives the movement of radical climate activists, including indigenous populations on all continents. It emphasizes the urgency of radical action and strives for the transcendence of capitalism and for building post-accumulation—or, as some would have it, ‘degrowth’—civilization, oriented towards harmony with nature rather than mastery of it. This current is far from the halls of power. But it has a generational cultural dynamic—as shown by the worldwide resonance of Fridays for Future—which may well have a lasting cultural impact, much like ’68.

A second perspective is centred on economic reform, encapsulated by the Green New Deal, of which there are many variants sharing a common de-fossilized Keynesian egalitarian economics. This programme should be compatible with mainstream social democracy, but it appears to have no significant mainstream endorsement. Politically, the vision was first developed by the British Labour left, then by dsa-aligned democratic socialists. In both cases it was defeated at the ballot box: the green policies of Labour’s 2019 Manifesto were swept aside by Johnson’s resounding victory, and the us Green New Deal was blocked by the House Democratic Caucus before even reaching the Senate floor. Green economic reform remains at the centre of the world’s political agenda, but its social momentum has dissipated. The eu’s post-pandemic investment package is mildly green but has no social-egalitarian ambition and is to be implemented under the steely gaze of the Commission.