Inequality is a modern notion. Differences in wealth, power and status—between rich and poor, men and women, young and old—are ancient, of course. The great salvationist religions—Buddhism, Christianity, Islam—adumbrated notions of the equality of human souls, which could sometimes develop into an egalitarianism rooted in this world, rather than the next: the celebrated defence of America’s native population by the Spanish priest Bartolomé de las Casas, for example, or the anti-slave trade campaign of Anglo-Saxon abolitionists. It supplied an inspiration for popular uprisings, from the German Peasant War of the 1520s to the great Taiping and Tonghak rebellions in nineteenth-century China and Korea. A Biblical extrapolation—‘When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?’—was popular in many European languages. But the modern, secular concept of equality was forged in the course of the struggle waged by Europe’s bourgeoisie against the ruling aristocracy—a struggle in which the official Church and its high clergy, of whatever variant of Christianity, opted for the latter, and later paid the price in the unique secularization of most of Europe.

The bourgeoisie’s struggle focused on existential equality in its legal form, challenging the privileges of the aristocracy and its claim, most salient in France, to be a superior type of human being to mere commoners. But this civic equality among the propertied and educated gentlemen of the Atlantic revolutions was soon challenged to the point of extinction by the convulsive social polarizations of industrial capitalism. Social inequality entered the political arena—and the intellectual agenda. But if equality may be seen as the defining value of the modern left, as Norberto Bobbio has argued, within working-class, progressive-nationalist and feminist movements it was usually embedded in and subordinate to other concepts—emancipation, liberation, socialism—or sat alongside concrete demands for jobs, fair wages, social security, sexual freedom, national independence, and so on. Now that several of these concepts have lost their self-evident character, while inequalities are mutating into new, more vigorous forms with the crumbling of their old institutional bulwarks, critiques of inequality and concerns with equality—as a process and a horizon, rather than a state—are becoming more central. It was Amartya Sen who, in this context, posed the question, ‘Inequality of what?’ and answered: ‘Of possibilities for human functioning.’footnote1 He thereby provided egalitarianism with a sustainable theoretical basis, relevant both to social philosophers, lost in the utopian nationalism of Rawls—that is, the radical utopianism of his Theory of Justice and the philosophical nationalism of his Law of Peoples—and to latterday economists, blissfully ignorant not only of Marx but also of Ricardo.

On this view, inequality is a historical construct. Under the present global order, the majority of humankind are deprived of the potential to realize their full capabilities. Six million children die annually before their fifth birthday; the chances of survival for those born into the world’s poorest 20 per cent are only half those for the richest quintile. In India, almost half the population suffers from physical and mental stunting in childhood, a handicap from which many will never fully recover. In Britain, too, the class imprint on babies is visible by the age of 22 months. In this sense, inequality is perhaps the biggest ‘crime against humanity’. Sen’s approach has been statistically codified in the Human Development Index produced by the un Development Programme, focusing on the dimensions of life expectancy, education and income. In recent years, the undp has also begun to calculate inequality of development within nations and regions: Sub-Saharan Africa fares worst overall, followed by South Asia; income inequality is highest in Latin America, educational inequality worst in South Asia and life expectancy most unequal in Sub-Saharan Africa.footnote2

Over the past twenty years, inequality has again become a major—or at least, non-negligible—preoccupation for economists; the 2008 financial crisis even put it on the agenda of the capitalist World Economic Forum in Davos. In a us-dominated profession, this egalitarian surge has largely been driven by Europeans—although many work at American institutions.footnote3 For many years a doyen in the field was the Nuffield-based Anthony Atkinson, a sharp-eyed British empiricist; from France there is the developmental economist François Bourguignon, a former chief economist at the World Bank, the economic historian Christian Morrisson, the economist-cum-historian Thomas Piketty and his sometime collaborator Emmanuel Saez, now at Berkeley; Italians include the global researchers Giovanni Andrea Cornia, formerly at unicef, and Andrea Brandolini; we should also include circumspect Dutch economic historians, like Jan Luiten van Zanden.

But for the lay person with a global perspective, the most interesting and important of these analysts of inequality is Branko Milanovic. Born in Yugoslavia in 1953, Milanovic trained as an economist at the University of Belgrade, where his earliest research centred on workers’ self-management. His doctoral dissertation, completed in 1987, examined economic inequality in Yugoslavia, pioneering the use of micro data from household surveys there. In the early 90s he moved to the us, joining the World Bank’s research department, and from 1996–2007 taught at jhu. His first major work demonstrated the rise of inequality in Eastern Europe with the restoration of capitalism there (or, in polite liberal lingo, the ‘transition from planned to market economy’).footnote4 Now at cuny, Milanovic has made his name as an empirical analyst of the totality of global economic inequality—in contrast, for example, to Piketty, who concentrates on the national income shares of the richest 10 to 1 per cent of selected countries’ populations.

In 2005, Milanovic’s Worlds Apart distinguished three different concepts of global inequality. The first compared the different countries of the world in terms of gdp per capita. This ‘un’ measure of inequality remained basically stable from 1950 to 1980—if we discount a blip around 1960, when a number of African countries became independent and were thus included in the statistics for the first time—and then rose steeply from 1980 to 1995, thereafter levelling off on a high plateau.footnote5 The second approach weighted the countries by population, giving due importance to China and India. By this measure, global inequality had been falling since the time series began in 1952: China’s growth rate had been negative between 1913 and 1950, while India’s had been barely zero; but from 1950 to 1973, they were 4.9 and 3.5 per cent respectively.footnote6 However, Milanovic’s most original contribution was his analysis of the primary data in the World Bank’s growing archive of national household surveys to produce a third measure of global inequality, this time potentially involving all the world’s household units; it was an approach that didn’t assume that every American or Chinese was receiving the average national income. Instead, the richest Chinese households might be ranked in the global top 1 per cent, while the income of working-class Americans would just allow them into the world’s top 20 per cent. This approach made it possible to grasp inequalities within countries and inequalities between countries within the same framework.footnote7

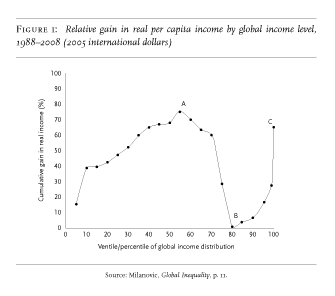

Milanovic’s latest book, Global Inequality, now offers a striking set of theses about the patterning and dynamics of inequality at a planetary level, with speculations on its future trends and political implications.footnote8 Drawing on his analysis of international household-survey data from 1988 to 2011—the era of high globalization, the fall of the Soviet bloc, the rise of China and the financial crisis—Milanovic offers a remarkable illustration of how the world’s income has been redistributed across the planet (Figure 1). Relative gains in real per capita income are calculated for each percentile of the global population, from the poorest to the richest 1 per cent. There are two main winners. The largest, group A, represents those between the 50th and 60th global percentiles, the ‘emerging middle class’ of China, India, Thailand, Vietnam and Indonesia. Their income has increased by 70 per cent or more since the late 1980s—though as Milanovic notes, ‘because they are still relatively poor compared with the Western middle classes, one should not assign to the term the same middle-class status (in terms of income and education) that we tend to associate with the middle classes in rich countries’.footnote9 The other winners, group C, are the top 1 per cent, whose incomes have risen by some 65 per cent; half of these are Americans—indeed, the top 12 per cent of Americans are all in the world’s top 1 per cent—and most of the rest are from Western Europe, Japan and Oceania. The big losers, group B, are at the 80th percentile of the global population, richer than the emerging Asian middle class; they are working-class and lower-middle-class Americans, Europeans and Japanese.