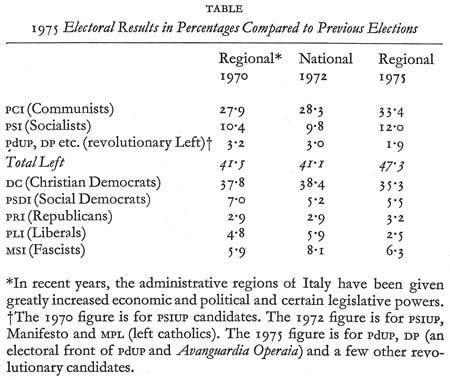

It is still too early to say whether the regional elections of 15 June 1975 marked the beginning of a new stage in the post-war history of Italy. What is, however, certain is that they left all the main actors in the country’s political life with their backs to the wall. The electoral shifts have resulted in major dislocations. To begin with, the bourgeois parties—the Christian Democrats (dc), the secular conservative Liberals (pli) and Social Democrats (psdi), and to a lesser extent the Fascists (msi)—have all been thrown into crisis. The solid bourgeois majority that has governed Italy for the past thirty years—since the crushing defeat of the Popular Front in 1948—is no longer solid. The Left—Communists (pci) plus Socialists (psi) plus the revolutionary Left (pdup, dp, etc)—won 47 per cent of the vote. However, the long social crisis opened in 1968–9 by the student upsurge and by the most extensive and radical workers’ struggles of the post-war period has also ended, at least temporarily. After seven years, this crisis has finally found a political outlet, has brought its weight to bear on the institutional equilibrium. Nevertheless, paradoxically, the protagonists of this political defeat of the

The real winner of 15 June was the pci, which nearly became the largest Italian political party. It has now acquired sufficient political and electoral weight to force its direct participation in the government, in one way or another, within six months or a year. If this happens, it will be the first time since the brief, atypical experience of the Popular Fronts of the immediate post-war period in France and Italy that a communist party participates in the government of an advanced capitalist society. Could this possibly happen without provoking a new fascist reaction? Or, on the other hand, without being rapidly transformed into a proletarian revolution? Or is it possible that the pci once in government will try, or more important be able to act like the British Labour Party or a Scandinavian social-democratic party? These are the questions posed by the victory of the Left on 15 June. They are strategic and dramatic questions, not only for the Italian Left. In this article, before offering, if not precise answers, at least some tentative predictions, we would like to reconstruct the overall social and political context within which such unexpected and striking changes became possible in a society as electorally stable as Italy.

As early as the spring of 1974 it was clear that the political balance in the country was changing. The referendum on divorce in May of that year, initiated by the most obscurantist sections of the Right, with the aim of repealing existing legislation which allowed divorce under extremely limited conditions, and then supported by the dc (at the

The Christian Democrats, then, lost the referendum. But who won? At the time, there were two widespread theories, both of which have since proved false. Some people maintained that the true victor was a brand-new bourgeois reformist front, secular and modern in character, which enjoyed the support of all the main bourgeois newspapers and included all parties from the pli across to the psi. This front could provide the basis for an alternative party of the bourgeoisie. After all, did not Gianni Agnelli (managing director of fiat and head of the employers’ association) support the Socialists (and vice versa)? However, in the year that followed the referendum, nothing occurred to confirm this hypothesis—no ideas, no programmatic initiatives, no agreements. As we shall see, the elections of 15 June 1975 delivered the coup de grâce to this theory.

According to a second common belief, the winners of the referendum were the radical sectors of the Left: the left wing of the psi, the Radicalsfootnote1, the groups of the revolutionary Left, and those few people within the pci, like Terracini,footnote2 who oppose the ‘historic compromise’ with the Christian Democrats. According to this theory, the referendum victory would convince the pci of the advantages of a frontal clash with the dc and consequently bolster the role of those who advocate the strategy of offering a ‘left alternative’ to capitalism and the dc. In short, the pci could be forced to shift to the left, and the revolutionary Left in all its forms was said to have been strengthened. In fact, however, neither of these two things had happened. Indeed now, a year and a half later, it can be seen that in both cases it is almost the opposite that has actually come to pass.

Paradoxical as it may seem, then, the real winner of the referendum was the Communist Party, which had not wanted the referendum to take place at all. Which had claimed that it was a ‘diversion’ from more

In the meantime, what was happening in civil society during 1974 and 1975? The situation of the working class was noteworthy in that it combined strength and immobility. After 1969, the Italian working class had won historic victories in the realms of wages, control over working conditions, and trade-union organization (forcing an end to the political division into three trade-union federations: the Christian-Democratic cisl, the Republican/Social-Democratic/Socialist uil, and the Communist/Socialist cgil, larger than the other two combined). Nevertheless, this dynamic was halted around 1974. The gains that had already been made were not necessarily lost, but the forward motion stopped.