This short New Year memoir meshes theorizations of two very different subject areas: geopolitics and interaction rituals. The genre, however, also calls for a dose of merry nonsense, which very much includes all sociological jargon. Yet, as-we-all-know-who-theorized-it, rituals must be performed and emotions generated – even at the scale of world-systems theory.

The emotion in this case is an entirely happy one. It was prompted by the ritual New Year postcard arriving from the South Pole itself, more precisely, the NSF Amundsen-Scott camp in Antarctica.

We met in 1992 in the long line at the ex-Soviet Embassy in Washington, D.C. The occasion was purely bureaucratic and at the same time fabulously historical. Confirming one of the boldest predictions of Randall Collins, the USSR had collapsed; and we now needed to claim our new citizenship from among no less than a dozen successor nations. This geopolitical fact was finally forced upon me earlier that morning by the fashionably dressed official at the visa section of the French Embassy:

– Your passport is still valid, but the issuing state has expired…

Desperately pressed for time, I flagged down a taxi in the middle of Georgetown and asked the driver (who looked distinctly Ethiopian to my Africanist eye) if he knew the location of the ex-Soviet embassy. The cabdriver turned to me with a broad, cordial grin and replied in perfect Russian: Konechno, znayu, dorogoi tovarisch! – Of course, I know, dear comrade! What a country it was! Do you remember the Ukrainian girls? Borsch and sour cream at the student canteen? He was in fact Ethiopian, with an engineering diploma from Kharkov Polytechnic in Ukraine.

The consular division of the ex-Soviet Embassy occupied a distinguished-looking mansion near Dupont Circle. A few dozen petitioners formed two lines. Following my instantly revived Soviet instincts, I quietly joined the much shorter one. An official-looking woman emerged from the ‘Strictly Service’ door of the consulate to collect our petitions and passports. She approached me with frosty directness:

– Young man, are you Jewish or scientist?

Astonished by this dichotomous categorization, I could only meekly extend to her my – still valid – Soviet passport. Barely glancing at it, the woman immediately ordered me into the much longer line:

– Here stand only the Jews who had long emigrated to Israel and gave up their Soviet citizenship. But now with all our democratization (she could not help a snort) they can get the new Russian citizenship and travel back (oh, she knew all those tricks) without a visa. But your government service (stress) ‘blue’ passport was issued by the Foreign Relations Directorate of the USSR Academy of Sciences. Clearly, you are a scientist.

As a document-carrying scientist, I had to accept the logic of her arguments.

The scientists’ line behaved in recognizable Soviet ways. The people were frustrated by the waste of time and the whole bizarre procedure of having to choose a new citizenship. Yet since the frustrations were directed at the consular officers behind the bullet-proof windows with the dusty blinds unceremoniously drawn down before our faces, the common emotion generated among us was a form of solidarity and even fraternization. This exponentially increased as we learned about the structural homologies of our trajectories and positions. Everyone originally came from one or another of the intersecting Soviet academic institutions; and presently we all found ourselves in roughly the same precarious situation at American universities as post-docs, visiting fellows or lecturers. And, of course, we were cursing, as usual, the ‘Power’ (Vlast) that ‘broke up the country but kept its old habits’.

Vladimir Papitashvili introduced himself first as if begging my pardon for standing ahead in the line. He turned out to be a geophysicist, and his work (about which he was as passionate as any good scientist) consisted of tracing the signs of climate change, which is why he had travelled around the world doing his research. Once in 1984, on his way to Antarctica, as Papitashvili fondly reminisced, he had stayed at a different, much more hospitable Soviet Embassy. The polar expedition had a long trip to make from Leningrad. Their heavy Il-18 transport planes had to refuel often, first in Simferopol in the Crimea; next in Cairo, Egypt; then in Aden, Southern Yemen; and again in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania; and ultimately (at this point I gasped, because I knew this route) …. in Maputo, Mozambique.

The Ilyushin-18 turboprop airplanes, painted bright red for the polar conditions, were a common sight in Maputo during their seasonal expeditionary migrations. The airfield at the 26th parallel in the southern hemisphere was situated in the capital of a newly liberated African country pursuing a ‘socialist orientation’. Mozambique offered the southernmost friendly airport that Soviet planes could use before making the final leap to the coasts of Antarctica. Polar expeditions usually had to wait a few days there for good weather along the route, because the heavy planes could not return to Africa from somewhere halfway. The explorers, facing a year amidst the polar cold and night, did not seem to mind spending a few days on the beaches of the Indian Ocean.

To my new friend, Maputo seemed a strange place, beautiful and warm but also (he carefully searched for the word) … adventurous. Once their plane was parked for the night at the airport, it was surrounded by a bunch of wild-looking young Soviets, some of them bearded. They were dressed in civilian pants, short-sleeves and sandals, yet were armed to the teeth. These volunteer guards were provided as a diplomatic courtesy to fellow countrymen pursuing an important scientific mission.

Of course, it all sounded damn familiar to me. Oh, how we hated the ‘volunteer’ night shifts assigned by the Embassy’s Komsomol committee. Who would want to feed mosquitoes all night long, sitting under the wings of the bright-red IL-18 while keeping guard against possible attack by Renamo rebels and South African saboteurs? We carried a hodgepodge of surplus weaponry procured from our friends at the Soviet military mission, because we were actually listed as civilian personnel. (I got the vintage Degtyarev machine gun stamped with the production date of 1942, the year of Stalingrad.) On these improvised patrols we really felt more like bait.

That was all in a previous and rather surreal life. Here, in a new and also quite surreal American life, I realized that I was standing next to the very same man whose expeditionary equipment I had once been prepared to defend to death. We hugged and yelled, to the amusement of our fellow scientists. Papitashvili and I turned out to be old acquaintances. Which, by the way, would not be the end of the coincidences. Twice again Papitashvili and I would be neighbours at various American campuses, drawn together by our nomadic trajectories in search of fellowships and grants.

At last, the stern-looking official came out to deal with our petitions. Having barely glanced at our Soviet passports, she immediately got to the business of state-imposed categorization and essentialization based on the tell-tale endings of our ethnic surnames: All right, Papitashvili, you must be a Georgian; and you, Derlugyan, are Armenian, aren’t you?

Papitashvili burst into hasty chatter, trying to explain that it was his father who had been Georgian but he himself was born in Kirovabad, Azerbaijan. (Oh? The official raised her eyebrows.) There, in Azerbaijan, his Russian mother worked at the railway station, while his father was serving his military draft, but they had divorced when young Volodya was just one year old. I learned later that the Papitashvilis were a princely Georgian lineage, who in the Soviet period had turned their cultural capital into the high status of old intelligentsia. The relatives from Tbilisi had disapproved of the junior’s affair with a Russian working-class girl from the railroad depot. But the child was eventually half-accepted into the family. During his student years in Leningrad, Vladimir could procure coveted free passes to the Bolshoi Drama Theatre – the famed ‘BDT’, a cult destination for the Soviet intelligentsia – where his uncle was none other than Georgi Tovstonogov, the revered Chief Artistic Director. Yes, Papitashvili was a typical Soviet: born in Azerbaijan to a Georgian father and Russian mother, he attended university in Leningrad, then worked for sixteen years in the heart of Siberia, in Yakutia, at the Institute for the Study of Permafrost. Of course, he knew hardly a word of Georgian.

Next came my turn to explain that I really did not know Armenian, although I knew some Ukrainian because that is what my maternal grandmother spoke to me at home in Krasnodar. The official interrogated me with a tone of bureaucratic suspicion in her voice: Krasnodar? Is that where the Cossacks are?

I felt as if the silver-capped bandoliers were already growing across my chest and replied proudly: Yes, we are the Kuban Cossacks!

The official shrugged: Haven’t you seceded along with the Ukraine? You should really ask the Ukrainians for a new passport.

I stood speechless. Had we really seceded from Russia? Who could know in those crazy days. Did I miss the news? The USSR emigrated from me in my sleep. Barely regaining the ability to speak, I asked meekly if the lady would, please, make sure that the Krasnodar territory was no longer part of Russian Federation. After all, it had been for the last seventy years… She looked at the map on the wall and said apologetically: All right, I am sorry, Krasnodar is still in Russia. It was the Crimea that had separated along with Ukraine. (Ah, the neighbouring province, and another Black Sea resort which for a Muscovite like herself must have all appeared the same.) Then she turned her head to Papitashvili and added: And Yakutia is also still in Russia although they now call it by some different name…

– Sakha! The Republic of Sakha-Yakutia, suggested Papitashvili, and hurriedly added: But my propiska registration is in the city of Moscow.

– Very well then, said the official: A hundred dollars from each of you. Cash or money order only.

– For what?! we cried in unison.

– For the stamp in your passports confirming your Russian citizenship.

– But does one pay to become a Russian in Russia?

At this point she finally burst:

– Look, dear scholars, you are all so smart, but this is not Russia, we are in Washington! And we have to pay for everything. Do you realize how expensive it is to renovate the consulate building? Look, look over there: the ceiling is cracking already over our heads. So, a hundred dollars each, and two standard 4×6 passport photographs. Or go to San Francisco, there the consulate charges 85 dollars.

Papitashvili sighed and reached for his wallet, but I simply did not have a hundred dollars, not even in the bank. The times were indeed desperate. I just scoffed:

– Big deal, Russian citizenship! I will apply for Armenian, because I am a Derlugyan, or Ukrainian because my mom is a Kuban Cossack and I can speak Ukrainian. Or, even better, the newly-appointed Kyrgyzstan ambassador is Rosa Otunbaeva, right? She is also a scholar and wrote her dissertation on the Frankfurt School. Otunbaeva has a stamp, and so far no embassy to renovate. I don’t mind becoming a Kyrgyz sociologist, especially if this comes for free. I just don’t have hundred dollars…

The official stared at me tenderly: Young man, do not attempt anything you might later regret. Russian citizenship is a valuable thing. Allow me a minute.

She went through the doors again, and returned a moment later to announce magnanimously:

– Given your difficult material circumstances, the Consul has consented to granting you the confirmation of Russian citizenship at the older rate of 50 dollars. Cash or money order.

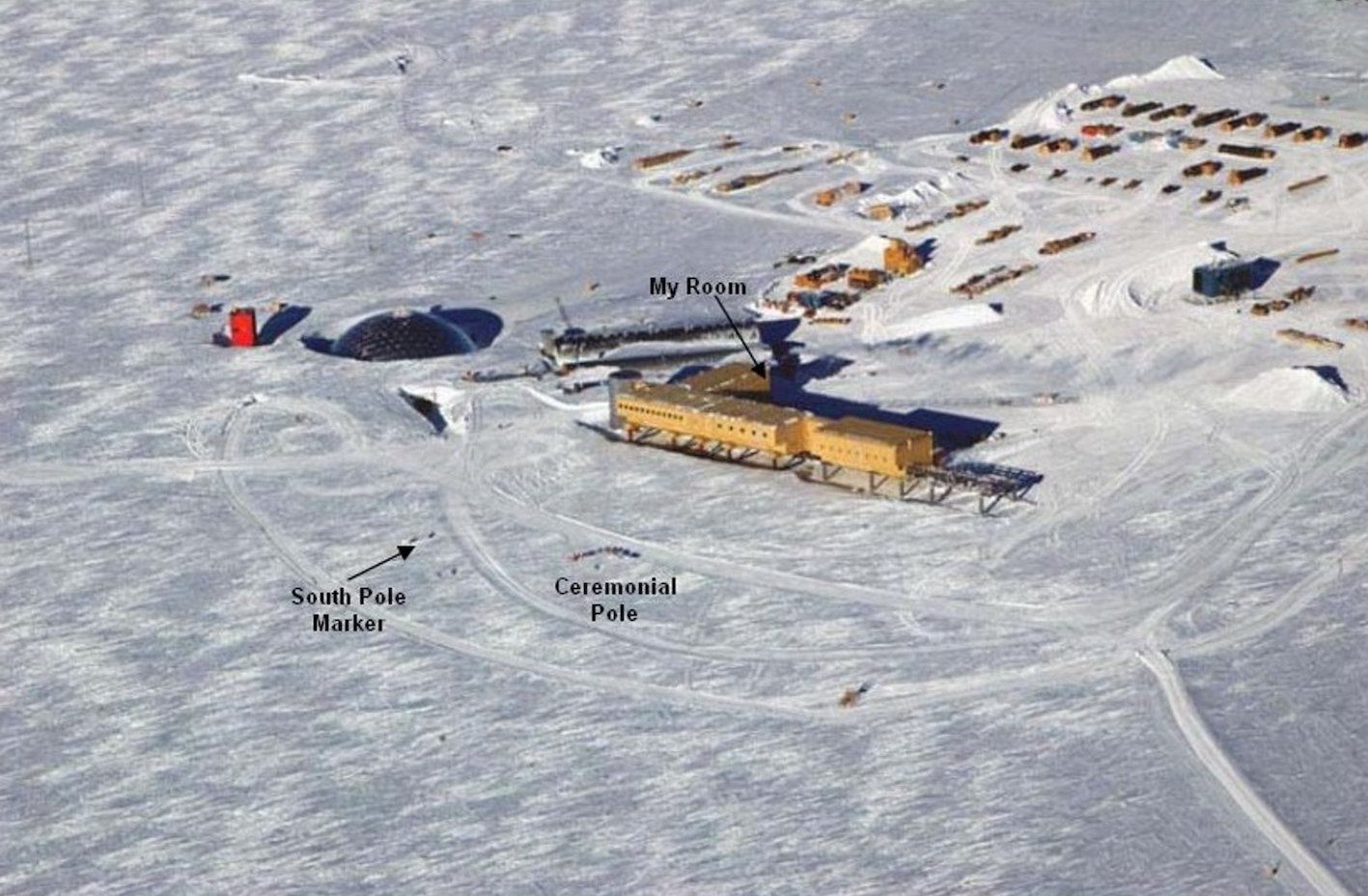

And that is how Papitashvili and I, the children of multi-ethnic Soviet parents, became the new Russian intellectual diaspora working in America. He is still following his satellites and drills holes in the middle of Antarctica, only now he is doing so as the head of the American NSF expedition (a good third of its personnel are former Soviet scientists anyway). And every winter/summer, Papitashvili sends his season’s greetings from almost exactly atop the South Pole.

С НОВЫМ ГОДОМ! HAPPY NEW YEAR!

Read on: Georgi Derluguian, ‘Recasting Russia’, NLR 12.