This August, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell delivered his annual address to top central bankers and economists, sparking what Bloomberg described as an ‘all-conquering Wall Street rally’. The reaction was in stark contrast to that which met his last two speeches at Jackson Hole. In 2022, a contrite Powell accepted he had been wrong about the recent bout of inflation being ‘transitory’ and committed to continued interest rate rises; in 2023, having raised rates to almost 5.5%, he announced they would have to stay ‘higher for longer’. On both occasions, markets plummeted.

This year’s rally appeared to rest on three claims: first, that inflation was ‘on a sustainable path back to 2%’, which meant it was ‘time for policy to adjust’; second, that while the labour market had ‘cooled considerably’, this was not because of ‘elevated layoffs’, as in a downturn, but rather ‘a substantial increase in the supply of workers and a slowdown from the previously frantic pace of hiring’. The Federal Reserve’s ‘dual mandate’ to keep inflation low and employment high therefore required it consider lowering rates in order to maintain a strong labour market. Of course, Powell cautioned that ‘the timing and pace of rate cuts will depend on incoming data, the evolving outlook, and the balance of risks’, but the overtones of his speech were clear: that he had won the fight against the inflation and effected a near impossible ‘soft landing’, stopping the economy from overheating without causing a downturn. Should we believe him?

To answer, it is necessary to consider the recent history of the Federal Reserve. Throughout the neoliberal era, it has subscribed – in practice if not explicitly in theory – to the Friedmanite view that ‘inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon’, and that the cure is therefore a reduction in the money supply. Most progressive economists reject this approach, arguing that it tends to lead to recession and high unemployment. Some claim that the Federal Reserve should be more tolerant of inflation, yet this would never do for a central bank committed to protecting the wealth of the richest. Nor would it be good news for the working class: countervailing forces like rapid growth and low unemployment would be necessary to mitigate inflation’s impact on living standards and allow unions to push wages up – and these are largely absent, given the US’s weak productive economy and volatile labour market. Others advise tackling price-gouging by big corporations. But this is only one factor in the recent inflationary upsurge, and the institutional pathways for combating it are unclear. Kamala Harris has already ‘walked back’ her anti-price-gouging plan after a corporate backlash, and a more determined leader would inevitably see such legislation challenged by the right-wing judiciary.

Since inflation, symptomatically at least, is ‘too much money chasing too few goods’, the least destructive way it can be addressed is by increasing the supply of goods and services whose prices are rising. Yet this would deprive the Federal Reserve of the near monopoly it has acquired over economic policy, and instead require a developmental state capable of pursuing an active industrial policy – not just directing credit, R&D, trade and investment flows, but controlling capital, rather than being controlled by it. This is a tall order. Progressive economists who gesture towards industrial policy often imagine that ‘Bidenomics’ is ‘bringing it back’. Yet, in reality, Biden’s programme has amounted to little more than massive corporate subsidies, and its success in reshaping the investment landscape has been limited.

With these options off the table, US authorities are reliant on only one institution – the Federal Reserve – to control inflation, and it has only one instrument to do so: interest rates. While its decisions are always justified in terms of the dual mandate, nothing in its record shows that it is particularly concerned about increasing unemployment or inducing a recession. Paul Volcker’s notorious 1979 hike, which marked the apex of the central bank’s monetarist zeal, took the interest rate to nearly 20%, induced a double-dip recession and sent unemployment north of 10% according to the conservative official estimate. Four decades on, the Federal Reserve remains nonchalant about the employment part of its mandate. But there is another sense in which the institution has changed radically. Volcker was able to take such drastic steps because neoliberalism was still in its infancy, as were the processes of financialization that it was about to unleash. It therefore had no need to worry about bursting asset bubbles. Today, the situation is different. Much as he would like to, Powell cannot replicate the Volcker Shock, because monetary tightening has come to contradict the interests of the capitalist class.

Volcker’s successor Alan Greenspan inaugurated his tenure as the Federal Reserve Chairman by rescuing markets from the 1987 financial crash with generous amounts of liquidity. This was dubbed the ‘Greenspan put’: a ‘put’ in market jargon being a contractual offer to buy an asset at a certain price without regard to prevailing prices, essentially a hedge against falling prices. Greenspan coupled this with unabashed cruelty towards workers, as he tried to ‘stay ahead of the curve’ by raising rates well before signs of the labour-market tightening. Yet these complementary goals – propping up asset prices and raising rates to keep workers in check – were set on a collision course as financialization evolved. In the late 1990s, the Federal Reserve’s rate rises pricked the stock market bubble. As it burst, the Greenspan put dictated that he reduce interest rates to historic lows, not only bailing out financial institutions, but also keeping the housing bubble growing and creating a credit bubble alongside it.

Later, when the worldwide commodities boom generated inflation and downward pressure on the dollar, the Federal Reserve was once again forced to resort to rate hikes. The effect was to burst the housing and credit bubbles, contributing to the 2008 financial crisis. In its wake, rates were taken even lower, to near zero, while Quantitative Easing and ‘forward guidance’ were used to revive asset markets. By then, such asset purchases became the means of sustaining the US’s heavily financialized growth model. Under Greenspan’s successors, the Federal Reserve put has facilitated private accumulation through speculative bubbles, while socializing the losses simply by creating more money.

Over the past decade and a half, for all the talk of financial reform, asset bubbles have grown to such an extent that they now constitute an ‘everything bubble’, which continues to expand while the real economy stagnates. Though the Federal Reserve took credit for keeping inflation low during this period, in fact it was suppressed by other factors. After the 1982 debt crisis, the US used its imperial power to force Structural Adjustment on much of the Third World while outsourcing production chiefly to China. It thereby kept the prices of key imports – primary commodities and outsourced manufactures – low, while imposing wage restraint on domestic workers. The 2020s brought this period of low prices to an end. The disruptions induced by the pandemic and compounded by trade tensions with China, plus the eruption of war in Ukraine, sent the costs of food and energy soaring. As inflation made a comeback, the Federal Reserve found itself in a fix. Because these asset bubbles rely on easy money, it cannot use the only means at its disposal to address rising prices.

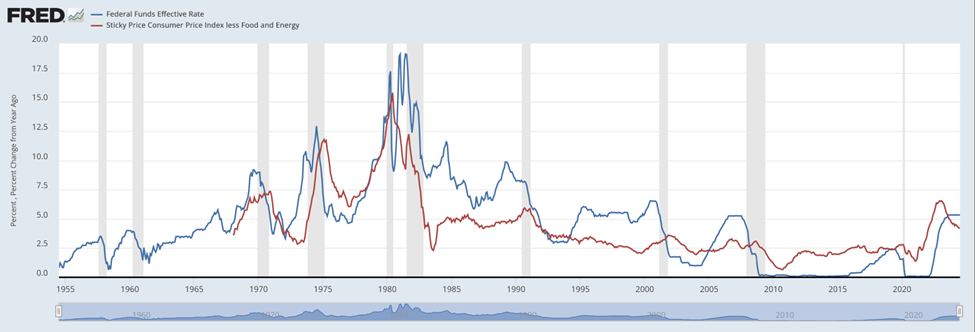

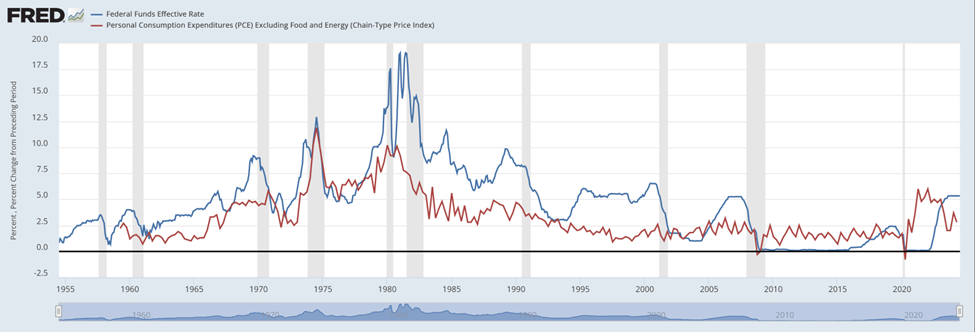

The following two charts reflect this dilemma. One plots interest rates against the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index, the metric most widely used to measure inflation, and the next against the Bureau of Economic Analysis’s Personal Consumption Expenditures, the metric preferred by the Federal Reserve when justifying the impact of its interest rate decisions on public consumption:

Three points are noteworthy. First, the Federal Reserve’s preferred inflation measure clearly understates inflation. It takes account of the ‘substitution’ that occurs when households shift to buying lower priced goods, effectively using households’ coping mechanisms as an excuse to artificially lower the inflation figures. It also gives a lower weighting to shelter costs, even though they have skyrocketed thanks to the housing bubble and the everything bubble. Second, since 2000, when the Federal Reserve accelerated its efforts to drive bubble-driven growth and changed its preferred inflation measure to PCE, the CPI has often been above the 2% target. No matter which inflation measure is used, inflation has generally been above interest rates during this period, making real interest rates negative. Finally, inflation today remains well above the 2% target, even if it has dipped below interest rates in recent months; yet the Federal Reserve flatly refuses to raise rates further, having brought them to 5.33% in July 2023. After all, this rise has already caused major ructions, from the failure of a string of banks beginning with Silicon Valley Bank to the instability in the commercial real estate, private equity and treasury markets and beyond.

Though the Federal Reserve claims that inflation is now down to 2.9% and predicts it will fall further, the Bureau of Labor Statistics disaggregation of the inflation numbers shows a rather different picture. While inflation has been dragged down by the lowering of food and energy prices, core inflation, a measure that excludes those prices because of their volatility, is still at 3.2%. With food and energy prices expected to increase in the coming months, not least thanks to continuing US and NATO warmongering, Powell’s declaration of victory may be premature.

What of his claim to have achieved a ‘soft landing’? There is equal reason to be sceptical. On the one hand, adverse jobs data suggest that a recession could still be looming. On the other, if interest rate cuts manage to prevent a recession, this leaves the door open to continuing inflation and ‘no landing’ at all. Raising the curtain on neoliberalism in 1979 with historically unprecedented rate hikes, the Federal Reserve has since, by nursing successive asset bubbles, deprived itself of the ability to use the only anti-inflationary weapon in its arsenal. Having arrogated to itself responsibility for managing the economy, it has now proven unable to do so.

Read on: Cédric Durand, ‘The End of Financial Hegemony?’, NLR 138.