A nation that is boycotted is a nation that is in sight of surrender. Apply this economic, peaceful, silent, deadly remedy and there will be no need for force. It is a terrible remedy. It does not cost a life outside the nation boycotted, but it brings a pressure upon the nation which, in my judgment, no modern nation could resist.

Never has the cruelty, the cold violence of economic sanctions, been better expressed than in these words, pronounced by the American president Woodrow Wilson at the Indianapolis Coliseum on 4 September 1919. The sanction is a ‘deadly remedy’; it ‘does not cost a life outside the nation boycotted’ – it only kills over there.

Wilson’s words remind us that – despite a handful of illustrious precedents we’ll return to shortly – sanctions became an ordinary practice only during the 20th century, and subsequently dominated the first two decades of the 21st. The League of Nations, born out of the Treaty of Versailles, stipulated in article 16 of its Covenant the possibility of imposing sanctions on states that had breached its rules, enjoining member states to, ‘subject it to the severance of all trade or financial relations, the prohibition of all intercourse between their nationals and the nationals of the covenant-breaking State, and the prevention of all financial, commercial or personal intercourse between the nationals of the covenant-breaking State and the nationals of any other State, whether a Member of the League or not.’

The first sanctions it passed were against Italy in 1935, when the fascist regime invaded Ethiopia (before leaving the League of Nations in 1937). Sanctions were also applied to Japan in 1940-41. OFAC, the Office of Foreign Assets Control of the US Treasury, was established in 1950. The Suez Crisis of 1956 – when France, Britain and Israel sought to block Nasser’s nationalisation of the canal – was resolved when the United States forbade Britain from using its IMF reserves to defend the Pound. The Cuban embargo of 1962 is the classic example of how the US used sanctions against the Soviet bloc during the Cold War. But the use and abuse of sanctions skyrocketed after the fall of the Berlin Wall (the first to feel their effect was Saddam Hussein).

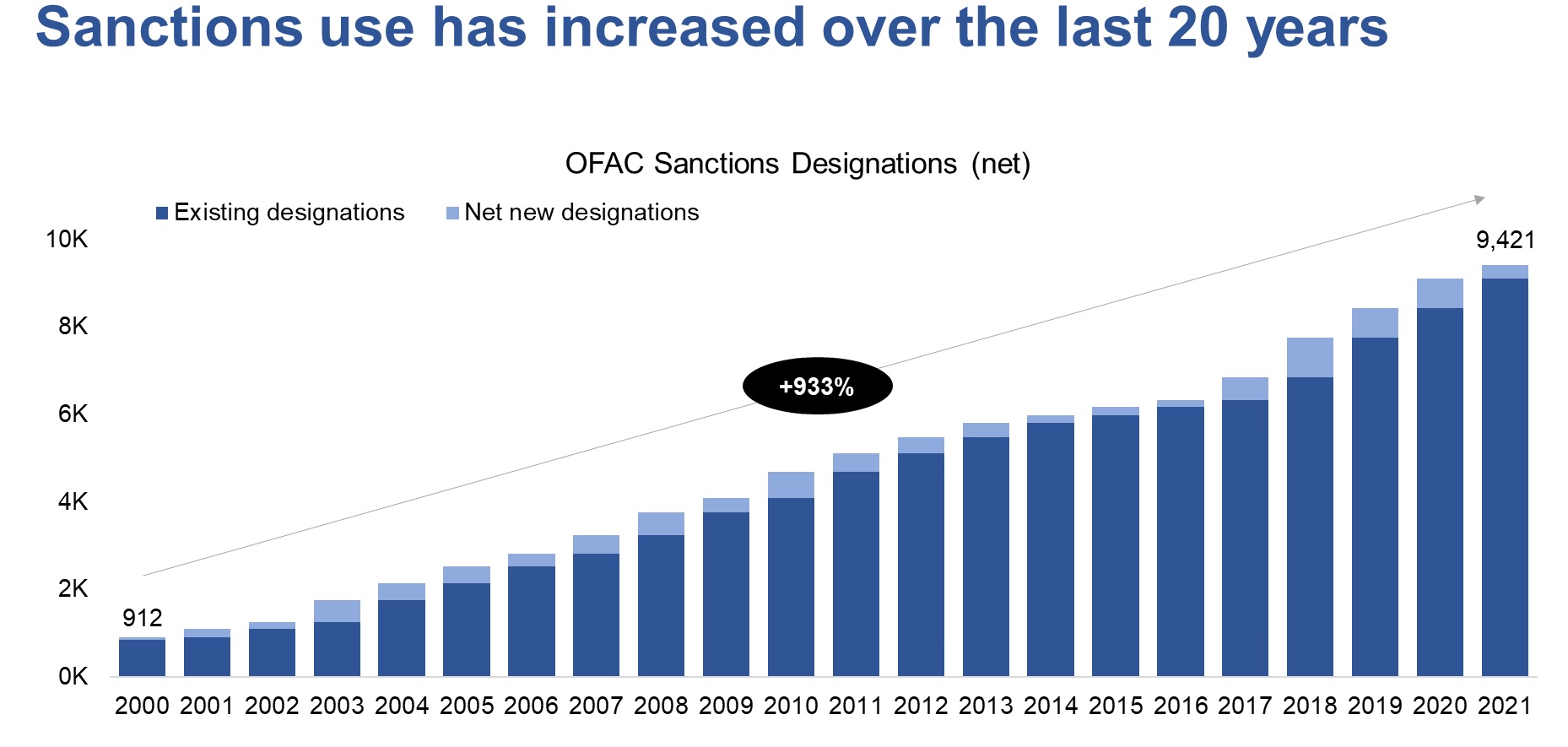

Wilson also reminds us that sanctions are acts of warfare – economic, to be sure, but warfare nonetheless. The growth of sanctions and of sanctioned states necessarily means the proliferation of warfare. In recent decades the tactic has been applied with increasing frequency, against ever more nations by a growing number of powers, proxies and sub-proxies (China against Lithuania; the European Union against Belarus; France against Mali; Saudi Arabia against Syria and Qatar). Naturally, the sanctioning power par excellence remains the United States. According to a report by the US Treasury, in the period from 2000 to 2021 sanctions issued by the United States increased by 933%: from 912 in 2000 to 9,421 in 2021.

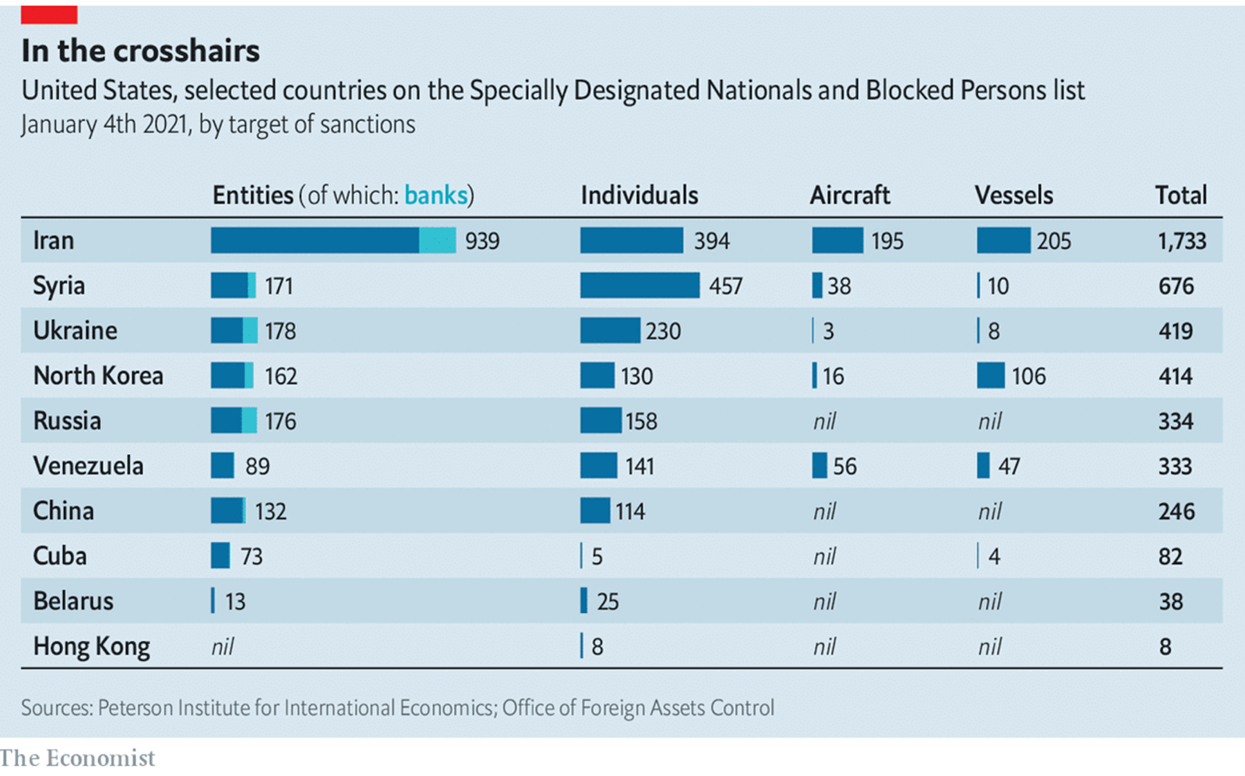

In parallel to their quantitative growth, sanctions have become more sophisticated. They’ve diversified to the point that they now represent a panoply of distinct weapons. Before imposing a nationwide sanction, you might target a single individual, a specific plane, even a particular ship. Today, OFAC administers and enforces 37 different ‘sanctions programmes’ targeting 12,000 different entities or designated persons. Visiting the website dedicated to these programmes is like entering a Kafkian labyrinth in which one risks losing oneself. Selecting randomly from individuals added to the SDN (Specially Designated Nationals) list last December, we find, for instance, Mr

FRAGOSO DO NASCIMENTO, Leopoldino (a.k.a. ‘DINO’), Luanda, Angola; DOB 05 Jun 1963; POB Luanda, Angola; nationality Angola; Gender Male; Passport N1999980 (Angola) expires 08 Apr 2036 (individual) [GLOMAG].

This gentleman, known as ‘General Dino’, was head of communications for the Angolan strongman José Eduardo do Santos between 2017 and 2019. But Dino also serves as the president of the board of the Cochan group, and is therefore sanctioned through the companies ‘Cochan Angola, Cochan Group, Cohan S. A., Geni Group, Geni Novas Tecnologias, Geni Novas Tecnologias S. A., Geni S. A., Geni Sarl’. If you then have a peek at the alphabetical list, you find under ‘A’: AFAGIR, the Aerospace Force of the Pasdaran; AFAQ, a Dubai-based company; a Russian national (Sergei Afanasyev) and his wife, Yulia Andreevna, and so on.

A table published by The Economist further clarifies the variety of these US targets. In Venezuela, for instance, the US has sanctions in place against 56 aeroplanes, 47 ships, 141 individuals and 89 juridical entities (including banks, companies, etc.). In North Korea, not even the Academy of Sciences is spared.

After the Cold War, as the US empire became mediated through globalization, these measures abounded, and financial sanctions became far more effective than the commercial variety.

Historically, commercial sanctions have scarcely been effective. One of the first recorded examples is the commercial blockade imposed by Pericles’s Athens against the city of Megara in 432 which, according to Thucydides, led to the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War. This is an idea Aristophanes seems to share in his Acharnians, in which the events leading to the embargo are described in a way that parodies the Trojan war, featuring a series of retributive kidnappings of Athenian and Megarian prostitutes:

Then Pericles, aflame with ire on his Olympian height, let loose the lightning, caused the thunder to roll, upset Greece and passed an edict, which ran like the song, ‘That the Megarians be banished both from our land and from our markets and from the sea and from the continent.’ Meanwhile the Megarians, who were beginning to die of hunger, begged the Lacedaemonians to bring about the abolition of the decree, of which those harlots were the cause; several times we refused their demand; and from that time there was horrible clatter of arms everywhere.

Aristophanes notes how the Megarians were ‘beginning to die of hunger’ – a fate they would share with a long succession of sanctioned peoples.

Twenty-two centuries separate this instance from two equally notorious commercial blockades which, when applied, both triggered a boomerang effect. The first was the Continental System, the ban on British ships in European ports declared by Napoleon in 1806. As we know, this move backfired and resulted in a British blockade against European commerce. The following year, Thomas Jefferson had an Embargo Act passed to punish Britain and France for harassing American ships. The measure proved disastrous, for at the time the US was more in need of European markets than the Europeans were dependent on American trade.

We might also recall that the embargo on oil and other raw materials that targeted Japan during the Second World War precipitated the attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941. Nor did the OPEC blockade of 1973 by oil-producing states greatly aid the Palestinian cause during the Yom Kippur War. The question about whether or not international sanctions were decisive in the fall of the apartheid regime in South Africa, too, has been subject of many inconclusive debates (it’s worth remarking that the end of apartheid followed closely on the heels of the Soviet collapse).

Following its annexation of Crimea in 2014, commercial sanctions – which Putin countered with his own embargo on food imports from Europe – did indeed cost Russia a few percentage points of GDP, but they also proved beneficial in a certain sense: sanctions forced Russia to replace the fruits of its raw material exports (crude oil, natural gas, timber, minerals) with domestic manufactures, pushing it to industrialize and acquire greater self-sufficiency – so much so that in January 2020 the Financial Times could run the headline: ‘Russia: adapting to sanctions leaves economy in robust health. Analysts say Moscow now has more to fear from removal of restriction than additional ones’.

More recent measures include the tariffs on Chinese products imposed by Trump in 2018, though as Daniel Drezner notes in a recent piece in Foreign Affairs,

if anything the sanctions backfired, harming the United States’ agricultural and high-tech sectors. According to Moody’s Investors Service, just eight percent of the added costs of the tariffs were borne by China; 93 percent were paid for by U.S. importers and ultimately passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices.

But this hasn’t dissuaded the disciples of sanctioning. China, for instance, has placed various sanctions on Australia, South Korea, Japan, Lithuania, and even the NBA. Russia has targeted various ex-Soviet republics. Even Saudi Arabia has tried its hand.

Financial sanctions, however, have proven far more efficient. Thanks in part to the dollar, the United States can, with a simple gesture, banish an entire country (or a company, bank, industry) from the global financial circuit: simply forbidding its use of the SWIFT code might suffice. I realized this the day my wife and I decided to send some flowers to an Iranian friend for her birthday – it was impossible, because florists in Tehran can’t receive transfers from credit cards. There you go: isolating a country from the network of global finance means you can’t even send flowers to a friend.

This type of sanction has another advantage: whilst commercial sanctions can be sidestepped, and cause black markets to prosper, financial measures are also applied to foreign partners of the target, in what are known as ‘secondary sanctions’. Anyone with financial ties to a sanctioned state is also singled out in turn, and thereby excluded from financial markets. The financial partners of a sanctioned entity become enforcers themselves. This mechanism works with commercial sanctions too, but it is less effective since loopholes are easier to exploit.

‘In 2014’, The Economist notes, ‘BNP-Paribas, a French bank, pleaded guilty to processing thousands of transactions involving countries blacklisted by America, paid an $8.9bn fine and was forced to suspend its dollar-clearing operations in New York for a year’. In fact, banks are reluctant to maintain ties with individuals from sanctioned countries even in the absence of any specific directives, due to the difficulty they would face in rescinding contracts in the event of future sanctions.

Even in this case, however, sanctions present certain inconveniences. The first is that it undermines the dominion of the dollar, and pushes other countries (including European allies) to find an alternative to the SWIFT system. After all, the boom in cryptocurrencies is fuelled in part by the attempt to escape the yoke of the dollar.

But what’s even more detrimental about sanctions becoming the principal – if not the sole – instrument of pressure in international relations, is that they are extremely difficult to repeal. ‘Presidents are always eager to impose sanctions but wary of removing them’, Drezner writes,

because it exposes leaders to the charge of being weak on foreign policy. This makes it difficult for the United States to credibly commit to ending sanctions. When Biden considered lifting a few sanctions on Iran, for example, Republican lawmakers criticized him as a naive appeaser. Furthermore, many U.S. sanctions – such as those against Cuba and Russia – are mandated by law, which means that only Congress can permanently revoke them. And given the polarization and obstructionism now defining Capitol Hill, it is unlikely that sufficient numbers of lawmakers would support any presidential initiative to warm ties with a long-standing adversary. Even when political problems can be overcome, the legal thicket of sanctions can be difficult to navigate. Some countries are subject to so many overlapping sanctions that they find themselves trapped in a Kafka-esque situation, unsure if there is anything they can do to comply.

If a state knows that even absolute submission to American diktats would be unlikely to lift its sanctions regime, then surely it would be reluctant yield. What’s the point of complying with demands if there’s no reward?

What’s more, it may be true that the US is the most powerful – and most global – empire in history, but if it continues to impose sanctions without revoking them it will end up antagonizing the entire planet. History reveals two types of sanctions, which differ according to their objective. The first kind aims to contain: economic measures are put in place to impede the growth of a country or alliance, as with the embargo against the signatories of the Warsaw Pact during the Cold War. In this case, the country hit by sanctions expects no concessions. Compliance is the objective of the second: to oblige a state to do – or not do – something specific; see the attempt to stop Iran from enriching uranium. But in the latter instance the US needs to extend a credible prospect of withdrawing its sanctions, and base this on the satisfaction of clear and well-defined conditions, rather than using it as leverage to escalate demands. The problem with the sanctions the US has passed in recent decades is that they ultimately require regime change, which targeted regimes clearly refute, preferring instead to shift the burden of sanctions onto their own people, as has occurred countless times from Cuba to Iran, Russia to Syria, Libya, Myanmar, Venezuela, and so on.

Nowadays US foreign policy is all stick and no carrot. It’s curious to hear Western TV networks (BBC, CNN, FRANCE 24) warning Africa of ‘Chinese generosity’, putting the beneficiaries of new infrastructure projects (subways, dams, railways) on guard against becoming prisoners of Chinese debt, as if Africans haven’t for decades been shackled to Western credit – the only difference being that after the formal end of colonialism the West hardly built anything in Africa again. For the last 30 years, since it began considering itself master of the world, the US has only shown its forbidding, irascible side; like the earthly version of Yahweh, that ‘jealous god’ that looks at Beijing’s proposals for the Belt and Road Initiative as a husband registers the smiles his wife gives to a rival suitor.

It’s not that Washington doesn’t realise the implicit risks of this one-dimensional turn in US foreign policy. The Americans know full well that rather than reinforcing it, too many sanctions weaken the empire. They’ve debated this for a while now, as the article in Foreign Affairs and various others in the international press demonstrate. The problem is that sanctions are often of a lethal efficacy – quite literally – but they are also easy, both practically (their enforceability) and politically (they are impressive, and it’s relatively simple for Congress to approve them). The point is that they’ve all but become a tic of global diplomacy, an automatic reflex to any and every contrariety: 9,421 sanctions in a single year means around 26 sanctions a day, more than one per hour. Before long we’ll be saying that war is the continuation of sanctions by other means.

What’s funny is that this growing web of sanctions undermines the very fabric of globalization, precisely because it places insurmountable obstacles in the way of the free circulation of commodities and, most of all, of capital. We could almost say that at this rate, the US will end up sanctioning itself.

Translated by Francesco Anselmetti.

Vira Ameli, ‘Sanctions and Sickness’, NLR 122.