The odds were huge. On one side, the might of the British state, the three parties of government, Buckingham Palace, the bbc—still by far the most influential source of broadcast news and opinion—plus an overwhelming majority of the print media, the high command of British capital and the liberal establishment, backed up by the international weight of Washington, nato and the eu. On the other, a coalition of the young and the hopeful, including swathes of disillusioned Labour voters in the council estates—the ‘schemes’—of Clydeside and Tayside, significant sections of the petty bourgeoisie and Scotland’s immigrant communities, mobilized in a campaign that was at least as much a social movement as a national one. Starting from far behind, this popular-democratic upsurge succeeded in giving the British ruling class its worst fit of nerves since the miners’ and engineering workers’ strikes of 1972, wringing panicked pledges of further powers from the Conservative, Labour and Liberal leaders. By any measure, the Yes camp’s 45 per cent vote on a record-breaking turnout in the Scottish independence referendum was a significant achievement. How did we arrive at this point—and where does the 18 September vote leave uk and Scottish politics?

The institutional origins of the 2014 Scottish referendum can be traced to 1976, when Callaghan’s minority Labour government was struggling to cement a parliamentary majority while implementing draconian imf cuts—the onset of neoliberal restructuring in Britain. The support of the minority nationalist parties—the Scottish National Party had won 11 Westminster seats in the October 1974 election, its best result ever, while Plaid Cymru had 3 mps—was bought with the promise of referendums about devolving limited powers to new Scottish and Welsh assemblies. In the event, though the Yes vote won the 1979 Scottish referendum by 52 to 48 per cent, turnout didn’t reach the high bar set by Westminster, so devolution fell by the wayside. Under the Thatcher government, Scotland underwent the same drastic social engineering as the rest of the uk: high unemployment, deindustrialization, hospital closures, council-house sell-offs. Tory unionism had traditionally been the largest electoral force in Scottish politics; in 1955 it had won an absolute majority of seats and votes. By 1997, after eighteen years of Conservative rule at Westminster, its vote north of the border had dropped to 18 per cent and it held not a single Scottish seat.

A second chance for devolution came in the 1990s, when Labour’s fourth crushing electoral defeat led Blair and Brown to begin a desperate search for Liberal Democrat and snp support to build an anti-Tory coalition. This short-lived alliance accounted for the only reformist measures—Scottish and Welsh devolution, an appointee-only House of Lords, a referendum on the voting system, a Freedom of Information bill—in New Labour’s 1997 manifesto, otherwise devoted to boosting economic competition and cracking down on crime. The aim of devolution, Blair underlined, was a limited delegation of responsibilities through which ‘the Union will be strengthened and the threat of separatism removed’. The Scottish Parliament was duly established in 1999 on a modified first-past-the-post voting system, which was intended to deny a majority to any party—especially the snp—and guarantee a Labour–Liberal coalition, which was indeed the outcome between 1999 and 2007.footnote1

Rise of the SNP

Yet, masked by the rotten-borough effect of the first-past-the-post system, the years of war and neoliberalism under the Blair–Brown governments steadily sapped support for New Labour. In the 90s and 00s, Scotland had again followed uk growth patterns, with the expansion of a low-end service sector—one in ten of the Glaswegian labour force works in a call centre—and the growth of household debt. On a smaller scale, Edinburgh played the role of London as a centre for booming, deregulated financial services and the media, while inequalities gaped—the run-down housing scheme of Dumbiedykes lies just streets away from Holyrood Palace and the state-of-the-art Scottish Parliament building. After the financial crisis, Labour-led councils avidly implemented the mandated public-spending cuts, closing care homes, squeezing wages and sacking workers. In successive Scottish Parliament elections Labour’s share of the popular vote fell from 34 per cent in 1999 to 26 per cent in 2011, with ex-Labour voters passing first to the Greens and the Scottish Socialist Party in 2003, and then, after the ssp’s collapse, to the snp in 2007. In local elections Labour lost overall control almost everywhere except Glasgow and neighbouring North Lanarkshire. Labour Party membership plummeted from 30,000 in 1998 to under 13,000 in 2010. Meanwhile the Liberal Democrat vote in Scotland collapsed after 2010, when the party entered government with the Tories in Westminster, once again to the benefit of the snp. The result was to give the snp an overall majority of 69 seats out of 129 in the 2011 Scottish Parliament, with 44 per cent of the popular vote—10 points more than Labour had ever won.

The snp’s manifestos had long included the commitment to hold a referendum on independence if it won a majority in the Scottish Parliament. After its sweeping 2011 victory, the party’s leader Alex Salmond duly declared that this plan would go ahead. The snp’s preference was for a triple-option referendum: Scotland’s voters would decide between full independence, the status quo or ‘maximum devolution’, meaning that the Holyrood Parliament would gain full fiscal and legislative powers, but Scotland would remain under the canopy of the uk state—the Crown, Foreign Office, Ministry of Defence and Bank of England—with regard to diplomatic, military and monetary affairs. ‘Devo Max’ was the option overwhelmingly supported by the Scottish people; with some polls putting this as high as 70 per cent. The snp leadership recognized that there was not—or at any rate, not yet—a majority for independence, but hoped they could in the short-to-medium term achieve Devo Max. With a triple-option ballot paper, Salmond would have been able to claim victory if the result was either independence (unlikely) or Devo Max (very probable).

Under Labour’s 1998 Scotland Act, however, all constitutional issues relating to the 1707 Treaty of Union between England and Scotland were reserved to Westminster. The question therefore was whether the referendum would be duly legitimated and recognized by the British government, or whether it would be an ‘unofficial’ one, essentially a propagandistic device, conducted by the Scottish Parliament. On 8 January 2012 the British Prime Minister took the initiative, announcing that his government would legislate for a referendum to be held. But Cameron specified certain conditions: it would be an In–Out referendum, with no third option on the ballot paper. His reasons were simple enough: he wanted to see the decisive defeat of the independence option, if not for all time, then at least for the foreseeable future, while simultaneously denying Salmond the easy victory of Devo Max. The risks involved seemed small—polls consistently showed minority support for independence, generally around 30 per cent. Like Blair, Cameron wanted to see ‘the threat of separatism removed’.

The Tories were willing to pay a high price for the In–Out option in the negotiations, however, conceding to the Scottish Parliament the temporary right not only to hold the referendum but to decide on the date, the franchise and the wording of the question. Salmond and his capable deputy Nicola Sturgeon could thus plump for a long campaign, a franchise extended to all voters registered in Scotland—regardless of country of origin—with the voting age lowered to sixteen, and a positive framing of the question. ‘Do you agree that Scotland should be an independent country?’—rather than, for example, ‘Should Scotland remain part of the uk?’—allowed the snp to campaign for an upbeat Yes instead of a recalcitrant No. These terms were sealed by the Edinburgh Agreement, signed by Cameron and Salmond for their respective governments at St Andrews House on 15 October 2012.

Why independence?

At this stage it’s worth briefly pausing to ask why and how the character of the uk state had become such a live political issue. Compared to the turbulent constitutional history of its European neighbours—France, Spain or Germany, for example—the very durability of the multinational parliamentary monarchy founded by the 1707 Act of Union between England and Scotland, might seem a brilliant success. Exploring these questions in earlier numbers of nlr, Tom Nairn sought to explain the lateness of Scottish nationalism as an organized political force—scarcely figuring during the ‘age of nationalism’ in the nineteenth century and attracting mass support only from the 1960s. Like England and France, he argued, Scotland had constituted itself politically as a nation very early, in the feudal period—hundreds of years before the late eighteenth-century invention of ideological nationalism as such. In the crucible of the Reformation, its late-feudal absolutism ‘collapsed as a vehicle for unity, and became a vehicle for faction’.footnote2 But while Scotland lost its political state and national assembly in the elite bargain of 1707, henceforth sending its mps to the Parliament of Great Britain at Westminster, it retained the legal, religious, cultural and institutional forms of its civil society, as well as a distinctive ‘social ethos’, all of which would go to make up a resilient ‘sub-national’ identity.

For Nairn, the key to the 1707 Union’s longevity lay in the English revolutions that preceded it. The magnates’ ‘crown-in-parliament’ settlement of 1688 had created a state in the image of the most dynamic section of the English ruling class—its precociously capitalist landed aristocracy. Rather than having to struggle against an ancien régime, the Lowland gentry could exploit an open political system and a fast-growing economy, then embarking on two centuries of overseas expansion. Sheltered by the British state, the Scottish industrial revolution seeded the Central Belt with its iron towns and engineering works, producing a vast new Scottish working class; gigantic shipyards spread along the Clyde. Nationalism for Nairn, as for Ernest Gellner, was closely associated with the unevenness of capitalist expansion and with latecomers’ struggle to master industrial development, experienced as a powerful outside force. But the Scottish bourgeoisie had already achieved industrialization, without any need to mobilize its working class on the basis of a national project. Far from sharing the dynamism of its economic base, Scotland’s political superstructure, as Nairn put it, simply collapsed, leaving the sub-nation merely a province.footnote3

With the end of empire and the deepening economic crisis of the 1960s and 70s, the problems of Britain’s archaic multi-national state—‘William and Mary’s quaint palimpsest of cod-feudal shards, early-modern scratchings and re-invented “traditions”’—began to surface.footnote4 In these conditions, Nairn argued, Scotland’s ‘sub-national’ cultural identity, combined with the promise of far-north energy reserves, provided raw material that could be politicized by the snp; he dated the rise of organized political nationalism to the party’s 1974 election success, on the slogan, ‘It’s Scotland’s oil!’. Nairn speculated that late-emerging separatist tendencies (‘neo-nationalisms’) in economically advanced sub-nations like Catalonia, the Basque Country or Scotland might be read as another type of response to uneven capitalist dynamics—in this instance, relative regional over-development. The context for their emergence was the declining status of their own ‘great state’, under us hegemony and the internationalization of capital, and the absence of any viable socialist alternative. Ever optimistic, Nairn suggested that this neo-nationalism was becoming ‘the gravedigger of the old state in Britain’ and as such, ‘the principal factor making for a political revolution of some sort in England as well as the small countries’.footnote5

Nairn’s historical account can be challenged on three main grounds. Rather than emerging during the medieval period, a unified Scottish nation only became possible after the Union of 1707, with the irrevocable defeat of Jacobite feudal-absolutist reaction at Culloden in 1746 and the overcoming of the 400-year old Highland–Lowland divide, which had previously acted as a block to it. ‘Scottishness’ certainly contributed to the formation of ‘Britishness’, but the opposite is also true: a modern Scottish national consciousness, extending across the territorial extent of the country, was formed in a British context and, for the working class in particular, in the tension between participation in and support for British imperialism on the one hand, and the British labour movement on the other. As a result, fundamental political loyalties, for both major classes, lay until relatively recently at the British rather than the Scottish level: Scottish national consciousness was strong, but Scottish nationalism was weak for the simple reason that it met no political need.footnote6

Second, it was not ‘over-development’ that led to the rise of the snp and the posing of the question of independence, but the determined push for neoliberal restructuring by successive Westminster governments—Tory, Labour or coalition. Though the snp is the palest of pink, it doesn’t take much to be positioned to the left of New Labour. In contrast to the Blair–Brown governments, the snp has safeguarded free care for the elderly, free prescriptions and fee-less university education; it has resisted water privatization and the fragmentation—read: covert marketization—of the nhs. While the snp leadership basically accepts the neoliberal agenda—happy to cut corporation tax or cosy up to Donald Trump—it has also managed to position itself as the inheritor of the Scottish social-democratic tradition.

A telling stand-off came when the snp introduced a bill to tax supermarket profits, over a certain level, with the money hypothecated for social spending. Scottish Labour allied with the Tories to block the bill on the grounds that this would be ‘detrimental to business’, ‘threaten jobs’, etc. In addition, Salmond is one of the few uk politicians capable of defying the Atlantic consensus—standing out against the Anglo-American imperialist wars, for example. The arena of the Scottish Parliament has also highlighted the fact that the snp is a more effective political machine than Scottish Labour, with substantial figures like Nicola Sturgeon, Fiona Hyslop, Kenny MacAskill, Mike Russell, John Swinney and Sandra White. This contrasts starkly with Labour, where the focus remains Westminster—its Holyrood representation, with very few exceptions, involves a cohort of shifty election agents, superannuated full-time trade union officials and clapped-out local councillors.

‘Yes’ as a social movement

The third reason for dissenting from Nairn’s view, however—and this is the point that needs to be stressed—is that for the majority of Yes campaigners, the movement was not primarily about supporting the snp, nor even about Scottish nationalism in a wider sense. As a political ideology, nationalism—any nationalism, relatively progressive or absolutely reactionary—involves two inescapable principles: that the national group should have its own state, regardless of the social consequences; and that what unites the national group is more significant than what divides it, above all class. By contrast, the main impetus for the Yes campaign was not nationalism, but a desire for social change expressed through the demand for self-determination. It was on this basis that independence was taken up by a broad range of socialists, environmentalists and feminists.footnote7 In an era of weak and declining trade unionism, popular resistance to austerity will find other means of expression. As the late Daniel Bensaïd wrote: ‘If one of the outlets is blocked with particular care, then the contagion will find another, sometimes the most unexpected.’footnote8 The Scottish referendum campaign was one of those outlets. Yes campaigners saw establishing a Scottish state not as an eternal goal to be pursued in all circumstances, but as one which might offer better opportunities for equality and social justice in the current conditions of neoliberal austerity.

The official ‘Yes Scotland’ campaign was launched on 25 May 2012. Even though Devo Max was absent from the ballot paper, the version of independence promoted by the snp closely resembled it: the new Scottish state would retain the monarchy, nato membership and sterling, through a currency union with the rump uk.footnote9 The intention was to make the prospect of independence as palatable as possible to the unconvinced by proposing a form which would involve the fewest possible changes to the established order, compatible with actual secession. However, as became clear during the campaign, most Scots voting for Yes wanted their country to be different from the contemporary uk. Campaigning alongside tens of thousands of snp members, many of them former Labour activists, was the Radical Independence Campaign, several thousand strong, which included the left groups, the Greens and the snp left, and played a key role in organizing voter-registration drives in working-class communities:

Because we recognized that the poorest, most densely populated communities must bear the most votes and the most ready support for a decisive political and social change, we canvassed these areas the hardest . . . We recognized early that those voters who would buck the polling trend would be those voters who don’t talk to pollsters and hate politicians; those voters who have told our activists: ‘You are the only people to ever ask me what I think about politics.’footnote10

A Sunday Herald report described ‘two campaigns’: one traditional and led by the suits, arguing in conventional media set-piece debates, the other a ‘ground war’, ‘one-to-one, door-to-door, intentionally bypassing the media’.footnote11 It was this ‘other’ campaign which drew in previously marginalized working-class communities—and which suddenly flowered, over the course of the summer, into an extraordinary process of self-organization. Over 300 local community groups sprang up, alongside dozens of other spontaneous initiatives—Yes cafés, drop-in centres, a National Collective of musicians, artists and writers, Women for Independence, Generation Yes. They were complemented by activist websites like Bella Caledonia, loosely connected to the anti-neoliberal CommonWeal think-tank.footnote12 As the Sunday Herald report put it: ‘Yes staffers knew the grass-roots campaign was working when they learned of large community debates they had not organized, run by local groups they did not know existed.’ Even Unionist opinion-makers in the London press felt obliged to report the packed public meetings, the debates in pubs and on street corners, the animation of civic life.footnote13 Glasgow’s George Square became the site of daily mass gatherings of Yes supporters, meeting to discuss, sing or simply make visible the size and diversity of the movement. It was as if people who were canvassing, leafleting or flyposting—activities which tend to be carried out in small groups—had to return to the Square to refresh themselves in a public space over which they had taken collective control. In the summer of 2014, Glasgow came to resemble the Greek and Spanish cities during the Movement of the Squares—to a far greater extent than in the relatively small-scale Scottish manifestations of Occupy. George Kerevan noted: ‘By the end, the Yes campaign had morphed into the beginnings of a genuine populist, anti-austerity movement.’footnote14

Project Fear

The No campaign, Better Together, with its focus-group tested slogan, ‘No Thanks’, was essentially run by the Labour Party—chaired by Alistair Darling, the ex-Chancellor of the Exchequer responsible with Brown for the deregulation of uk banks, and directed by Blair McDougall, who had organized David Miliband’s failed Labour leadership bid—though its platform included local Tories and Liberal Democrats, to the embarrassment of many Labour functionaries, who preferred to claim that the whole referendum campaign was a waste of time.footnote15 The core concern of the uk’s governing class was summed up by the Economist: ‘The rump of Britain would be diminished in every international forum: why should anyone heed a country whose own people shun it? Since Britain broadly stands for free trade and the maintenance of international order, this would be bad for the world.’ The point was amplified for a Washington audience by George Robertson, Blair’s Minister for Defence during the war on Yugoslavia, then nato Secretary General: Scottish independence would leave ‘a much diminished country whose global position would be open to question’; it would be ‘cataclysmic in geopolitical terms’. footnote16

The uk elite’s sense of world entitlement was not, of course, foregrounded by Better Together, whose managers dubbed their strategy Project Fear.footnote17 Though the No campaign got off to an underwhelming start—Darling was a wooden performer, Brown was sulking and refused to participate—this did not matter much, since its real cadre was provided by the media, above all the bbc. An analysis of media coverage halfway through the campaign found that stv’s News at Six and the bbc’s Reporting Scotland typically presented the No campaign’s scaremongering press releases as if they were news reports, with headlines such as: ‘Scottish savers and financial institutions might be at risk if Scotland votes for independence’, ‘Row over independence could lead to higher electricity bills’. In terms of running order, Reporting Scotland typically led with ‘bad news’ about independence, then asked a Yes supporter to respond. Presenters put hard questions to Yes supporters, passive soft-balls to Noes. Yes campaigners were consistently referred to as ‘the separatists’ or ‘the nationalists’ even when, like the Scottish Green Party’s Patrick Harvie, they explicitly denied the label. ‘Expert opinion’ from the uk government side—the Office for Budget Responsibility, Institute for Fiscal Studies, Westminster committees—was treated as politically neutral, while Holyrood equivalents were always signalled as pro-snp. The Yes campaign was repeatedly associated with the personal desires of Alex Salmond—‘Salmond wants’—while no such equation was made for No figures. The air-time for the No campaign was bumped up by responses from all three Unionist parties to any statement from Salmond.

Television news reports often ended with particularly wild and unsubstantiated statements—that gps and patients were planning to move to England (Reporting Scotland); that the snp’s anti-nuclear policy would bring ‘economic disaster’ (stv); that insurance companies were looking at ‘billions in losses’ and ‘potential closures’ (Reporting Scotland).footnote18 The result was to radicalize Yes campaigners’ understanding of the media, since the experience of their own eyes and ears was so fundamentally at odds with what they saw on tv. One example out of hundreds is the way the bbc ignored a 13 September Yes demonstration of 10,000 people at the top of Glasgow’s Buchanan Street, yet filmed Labour No supporters Jim Murphy and John Reid with perhaps thirty supporters at the bottom of the same street.

The print media was less homogeneous. In addition to Scottish editions of the London press—Guardian, Independent, Telegraph, Mail, Express and the Murdoch stable—the ‘native’ Scottish press consists of The Scotsman, the Herald, the Daily Record and their separately edited Sunday editions. Only the Sunday Herald called for a Yes vote, and that quite late in the day, although the Herald itself and, to a lesser extent, the Daily Record were relatively balanced; both Darling and Salmond edited special editions of the latter, for example. But even so, No campaign themes were given overwhelming prominence. Foremost among these were the currency, job losses from companies flocking south, budget deficits leading to cuts in the nhs (a Record favourite), anxiety about pensions (particularly for the Express, whose readership is mostly over 65), increased taxes (Scottish Daily Mail) and rising prices in supermarkets. A sub-theme was security: would nato still want us? Would Russia invade? Would isis blow up the oil platforms? Finally, there was the ‘proud Scot’ theme—you can be patriotic and still vote No.

While the Scottish press kept up the relentless drumbeat of Project Fear, London’s left-liberal unionists painted the Yes campaign as semi-Nazis, bringing ‘darkness’ upon the land. For Will Hutton, Scottish independence meant ‘the death of the liberal enlightenment before the atavistic forces of nationalism and ethnicity—a dark omen for the 21st century. Britain will cease as an idea. We will all be diminished.’ For the editor of the New Statesman, ‘the portents for the 21st century are dark indeed’. For Martin Kettle, the ‘dark side’ of the Yes campaign—‘disturbing’, ‘divisive’—must not be ignored. For Philip Stephens, Salmond had ‘reawakened the allegiance of the tribe’.footnote19Guardian readers were treated to Labourist unionism in a variety of modes, from an upbeat Polly Toynbee—‘It’s no time to give up on a British social-democratic future’—to a doom-struck Seumas Milne: ‘The left and labour movement in Scotland, decimated by decades of deindustrialization and defeats, are currently too weak to shape a new Scottish state.’ This was the argument parodied decades ago by Nairn: ‘The essential unity of the uk must be maintained till the working classes of all Britain are ready.’footnote20

Darling and McDougall had early on identified the snp’s position on sterling as a weak point. Chancellor George Osborne came to Edinburgh in February 2014—a rare visit by a Tory government minister, since they themselves agreed their presence would be unhelpful—to announce that all three Unionist parties had agreed to refuse to allow Scotland to join a currency union with sterling.footnote21 The snp’s unspoken preference for Devo Max was a major handicap here: a really determined new-state project would have developed and costed plans for an autonomous currency. The No campaign seized on Salmond’s unwillingness, in the first televised debate with Darling on 5 August, to say what his Plan B would involve if London refused to agree to a currency union. His only argument was that this would be irrational and self-defeating for the rest of the uk. As he pointed out subsequently, and as Sturgeon might have said straight away, there were at least three other options: using the pound as a floating currency, adopting the Euro or establishing a Scottish currency. The problem with Salmond’s position was precisely the danger that London would have agreed to a currency union: a nominally independent Scotland would have remained under the tutelage of the Bank of England and the Treasury, which would have imposed an ecb-style fiscal compact—a recipe for permanent subjection to the neoliberal regime.

The panic

By the end of August, the groundswell for independence was starting to make itself felt in the polls. On 7 September a YouGov poll in the Sunday Times put Yes in the lead for the first time with 51 per cent. Two days later a tns poll put it just 1 point behind. The reaction was nicely captured by a Financial Times headline: ‘Ruling elite aghast as union wobbles’.footnote22 Darling’s leadership of the Scottish No campaign came in for scathing comment. Project Fear was ramped up from headquarters in Downing Street.footnote23 The press let it be known that the Queen was anxious. Big companies started warning their Scottish employees that independence would put their jobs at risk: Shell and bp suggested there could be redundancies in Aberdeen and Shetland; Royal Bank of Scotland, Lloyds, Standard Life and Tesco Bank announced that they might shift jobs from Edinburgh to London; Asda, John Lewis, and Marks & Spencer warned of rising prices. Some firms wrote to individual staff members, stressing the threat to their employment—a none-too-subtle hint about how they were expected to behave in the polling booth.

Ever eager to do its bit, the bbc broadcast the news of rbs’s decision to relocate its registered office to London on the evening of September 10, on the basis of an email from Osborne’s flunkeys at the Treasury, though rbs itself didn’t make the announcement until the following morning.footnote24 Scotland’s trade-union bureaucrats also put their shoulders to the wheel. Most full-time officials were hostile to independence, though few unions could openly align themselves with the No campaign without consulting their members, many of whom had voted snp in 2011.footnote25 At branch level, things were different. In the case of Unite (transport and general workers), union officials in aerospace and shipbuilding actively courted Tory ministers and Labour No mps for meetings to ‘defend the defence industry’. In some workplaces ceos and managers organized ‘employee briefings’, in effect mass meetings to agitate for a No vote, with the union representatives backing up the employers.

With great fanfare, Gordon Brown also lumbered into the campaign, giving a verbose and barely coherent speech at a rally in the Glasgow district of Maryhill, intended to staunch the flow of Labour voters to Yes. Having backed five wars, pioneered ppi hand-outs and presided over a steep increase in inequality during his thirteen years in office, he now maundered about ‘solidarity and sharing’ as defining features of the uk state.footnote26 Brown has a tendency to think that only he can save the world, as he revealed in October 2008 when he pledged the entirety of British gdp, if needed, to bail out his friends in the City. With no mandate—he is a backbench opposition mp—he announced a fast-track timetable towards greater devolution to reward a No vote. In fact, this was merely consolidating the promises made by all three Unionist party leaders after the September 7 poll had showed Yes in the lead.

Two days before the vote, Cameron, Clegg and Miliband appeared on the front of Labour’s loyal Scottish tabloid, the Daily Record, their signatures adorning a mock-vellum parchment headed ‘The Vow’, affirming that the Scottish parliament would be granted further powers if only the Scots would consent to stay within the Union.footnote27 Cameron had been so determined to exclude the Devo Max option from the ballot paper that he gave way to the snp on everything else. Now the uk leaders had unilaterally changed the nature of the question: from being a choice between the status quo and independence, it had effectively become a choice between independence and some unspecified form of Devo Max. Exit polls would suggest that ‘The Vow’ had a relatively limited effect: according to Ashcroft, only 9 per cent of No voters made up their minds during the last week of the campaign, compared to 21 per cent of Yes voters. The undecideds were still breaking 2:1 for yes in the last days of the campaign, although this couldn’t overcome the massive initial advantage of the Unionists.footnote28 As for Brown’s intervention: on the best estimates, around 40 per cent of Labour voters just ignored him.

The vote

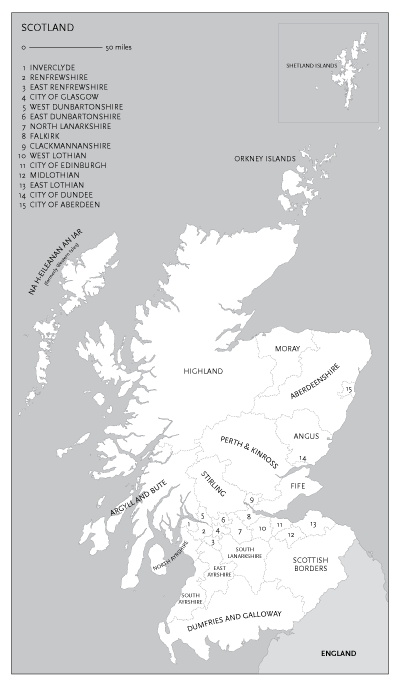

By the time the electoral rolls closed on 2 September 2014, some 97 per cent of the Scottish population had registered to vote: 4,285,323 people, including 109,000 of the 16- and 17-year-olds specially enfranchised for the occasion. This was the highest level of voter registration in Scottish or British history since the introduction of universal suffrage. By the time the ballot closed at 10pm on 18 September, 3,619,915 had actually voted, an 85 per cent turnout, compared with 65 per cent in the 2010 British general election. The popular vote was 2,001,926 for No, 1,617,989 for Yes, or 55 to 45 per cent against Scotland becoming an independent country. The demographics were telling. The No vote was heavily weighted towards the elderly: a clear majority of over-55s voted no, including nearly three-quarters of over-65s, many giving pensions or fears about savings and the currency as the main reason. Women were slightly more inclined to vote No than men, though that may partly reflect female predominance in the older age groups. Among under-40s there was a clear majority for Yes, with the strongest showing among 25–34 year olds, 59 per cent of whom voted for independence.footnote29 Based on pre-referendum polling, a significant majority of Scots of Asian origin voted Yes. In general, the No vote was correlated with higher income and class status; in the poorest neighbourhoods and peripheral housing schemes, the Yes vote was 65 per cent; it was from this group that most of the new voters emerged. One striking feature was the clash between the referendum results and regional party loyalties. The working-class Yes vote was concentrated in what were formerly the great heartlands of Labour support, above all in Dundee (57 per cent Yes) and Glasgow (54 per cent Yes), with similar results in North Lanarkshire and West Dumbartonshire; Inverclyde came within 88 votes of a Yes majority. On the other hand, Aberdeenshire, ‘Scotland’s Texas’ and an snp stronghold which includes Salmond’s Holyrood constituency, voted against independence.

In some respects the closest comparator would be the Greek election of June 2012, in which New Democracy, Pasok and Dimar won by 2 points over Syriza by mobilizing the financial anxieties of pensioners, housewives and rural voters, while the young and the cities voted to resist the predations of the Troika.footnote30 One difference lies in the Scottish legacy of a larger ‘formal’ working class, now ageing and mortgage-paying, with understandable fears for their jobs and pensions in conditions of crisis and austerity. For the vote of the working class—still the majority of the Scottish population—was deeply divided. Personal testimony from a Yes campaigner in Edinburgh on the day of the referendum gives a vivid sense of this:

I visited two areas to get the Yes vote out. The first one was Dryden Gardens [in Leith] which was made up of mainly well-paid workers and pensioners living in terraced houses. On the knocker, half of them had changed their vote or were not prepared to share their intentions with me . . . Following this, I walked round the corner to Dryden Gate, a housing scheme of predominantly rented flats that were more blue-collar, with a large number of migrant families. Every Yes voter I spoke to had held firm and had already voted or were waiting on family to go and vote together.footnote31

The social geography of the vote bears this out. The No heartlands lay in the rural districts—Dumfries and Galloway (66 per cent No), Aberdeenshire (60 per cent No)—and in traditionally conservative Edinburgh (61 per cent No). The only town of any size in Dumfries and Galloway is Dumfries itself, with a population of just over 30,000. The economy is dominated by agriculture, with forestry following and—some way behind—tourism. Two relationships are crucial: one with the eu through the Common Agricultural Policy, so the threat of exclusion, even for a limited time, had obvious implications for farmers and their employees; the other with England—Carlisle is closer than any Scottish city and many family and business links are closer with Cumbria than with other areas in Scotland. Aberdeenshire, too, is a conservative rural area with relatively small towns, in which the Tories were the main political force before the rise of the snp (the Conservatives are still the second-biggest party in the council). The main source of employment is the public sector—the local council, education and health—but the second biggest is energy, with the majority in jobs related to North Sea oil; the gas terminal at St Fergus, near Peterhead, handles around 15 per cent of the uk’s natural gas requirements. Understandably, the threat of the oil companies relocating was a major issue here, as it was in Aberdeen itself. The third biggest sector by employment, agriculture and fishing, has a complex relationship with the eu but, as in the case of Dumfries and Galloway, for farmers receiving subsidies the uncertainties over continued membership would have had an effect. Finally, Aberdeenshire has the highest growth rate of any local council area and the fastest growing population in Scotland, which might have been seen as vindicating current constitutional arrangements.

Edinburgh, the historic capital of Scotland, has a long history of Toryism and elected a Labour-majority city council for the first time only in 1984 (it is currently run by an snp–Labour coalition). Outside London, it has the highest average gross annual earnings per resident of any city in the uk, and the lowest percentage of those claiming Jobseeker’s Allowance (the typically New Labour term for unemployment benefit). It has both a disproportionately large middle class and a significant section of the working class employed in sectors supposedly threatened by independence, including higher education—the University of Edinburgh is the city’s third biggest employer—and finance: rbs, Lloyds and Standard Life are respectively its fourth, fifth and sixth. The only parliamentary constituency here which came close to voting for independence was Edinburgh East (47 per cent Yes), which contains some of the city’s poorest schemes, such as Dumbiedykes.

The strongest Yes vote, meanwhile, came in Dundee (57 per cent Yes). Scotland’s fourth largest city after Glasgow, Edinburgh and Aberdeen, it has the lowest level of average earnings of them all and one of the highest levels of unemployment. The staple industries of shipbuilding, carpet manufacture and jute export were all shut down in the 1980s; the city saw one of the most important British struggles against de-industrialization in the ultimately unsuccessful 6-month strike to prevent the closure of the Timex plant in 1993. The biggest employers—as in most Scottish cities—are the city council and the nhs, although publisher (and anti-trade union stalwart) D. C. Thompson, and the Universities of Dundee and Abertay are also important. (The latter has carved a niche in the video-games sector: Rockstar North, which developed Grand Theft Auto, was originally founded in Dundee as dma Design by David Jones, an Abertay graduate.) Although manufacturing has slumped, companies like National Cash Register and Michelin are still notable employers. Formerly a Labour stronghold, Dundee has sent an snp mp to Westminster since 2005. In the aftermath of the referendum there was a particularly angry demonstration outside the Caird Hall there, ostensibly to call for a re-vote, but which turned, via an open mic, into an all-purpose expression of rage at the conditions which had led a majority of Dundonians into voting Yes in the first place.

The Strathclyde Yes vote in the heart of the former Red Clydeside—straddling Glasgow, North Lanarkshire and West Dunbartonshire—was the biggest catastrophe for Labour. As noted, the first signs of its eroding support came after the invasion of Iraq in 2003, when a left protest vote sent 7 Green, 6 Scottish Socialist Party and 4 radical independent msps, including Dennis Canavan and Margo MacDonald, to Holyrood. The snp began to make real inroads into the Labour vote in Glasgow only in 2011, after the local council set about cuts and closures in the wake of Brown’s pro-City handling of the financial crisis. It is not hard to see why. Though Liverpool and Manchester have similar levels of deprivation, premature deaths in Glasgow are over 30 per cent higher; mortality rates are among the worst in Europe. Life expectancy at birth for men is nearly 7 years below the national average; in the Shettleston area it is 14 years, and in Calton 24 years, lower than the averages in Iraq and Bangladesh. What was once one of the most heavily industrialized areas in Europe is now essentially a services-based economy, dominated—the usual story—by the city council and nhs, but with significant low-paid employment in retail and ‘business services’, i.e. call centres. The city is growing again, but on a strikingly uneven basis—demonstrated by the heritage-makeover of the Clyde Walkway area and the Merchant City.

A mottled dawn for Labour

Though it is too early to take the full measure of this watershed vote, one paradox stands out. Scottish Labour has been drastically undermined by its victory, while the snp and the radical independence movement have been strengthened in defeat. This is immediately clear at the party level. Within ten days of the referendum, the membership of the snp had leapt from 25,642 to 68,200, while the Greens had more than tripled, from 1,720 to 6,235. When the Radical Independence Campaign announced it would be holding a ‘Where Now?’ conference in Glasgow on 22 November, 7,000 people signed up for it on Facebook and the venue had to be shifted to the Clyde Auditorium. A rally in George Square called by Tommy Sheridan’s Hope Not Fear operation in support of independence pulled an estimated 7,000 on 12 October. Post-referendum polls indicated the possibility of a swing to the snp that could make serious inroads into Labour’s tally of seats at the 2015 Westminster election.

Meanwhile Scottish Labour has collapsed into fratricidal strife after the resignation of its leader Johann Lamont, who accused Miliband and his claque of being ‘dinosaurs’, out of touch with how the Scottish political landscape had changed, and of treating the party north of the border as a ‘branch office’. Lamont’s long list of grievances included being elbowed aside during Miliband’s Beria-style takeover of the Falkirk selection process in 2013,footnote32 having her general secretary sacked by London, and being told she must not open her mouth about the Coalition’s deeply unpopular Bedroom Tax until Miliband had made up his mind about it—a notoriously lengthy process. The many resignations from Scottish Labour include Allan Grogan, a convenor of the Labour for Independence group, widely derided by the leadership, who described the party as being ‘in deep decline, and I fear it may be permanent’.footnote33

The snp has submitted a 42-page document demanding that the Scottish Parliament have the right to set all Scottish taxes and retain the revenues, to determine all domestic spending, employment and welfare policy, including the minimum wage, and to define Scotland’s internal constitutional framework—in short, Devo Max. The Unionist parties’ proposals are set to fall well short of this. There is an obvious danger here into which Yes campaigners may be led by an understandable wish to see the Unionist parties keep their promises: the danger is Devo Max itself. Under neoliberal regimes, the more politics is emptied of content, the more opportunities for pseudo-democracy are multiplied: citizen-consumers may take part in elections for local councillors, mayors, police commissioners, and so on, spreading responsibility to bodies whose policy options are severely restricted both by statute and by reliance on the central state for most of their funding. The upshot at local-council level has seen atomized citizens given a vote on which services they want to close. If this is to be the basis of ‘further devolution’ in Scotland, it should be rejected. Devo Max will be of value only insofar as it involves the greater democratization of Scottish society, rather than tightly circumscribed ‘powers’ for the Scottish sub-state.

Labour and the Conservatives are also at loggerheads over Cameron’s dawn pledge—at 7am on the morning after the referendum—of ‘English votes for English laws’ if further powers are devolved to Holyrood. Since 41 of Labour’s 257 mps are from Scottish constituencies, this would slash its voting weight in the House of Commons. The obvious solution to the ‘West Lothian’ question—the constitutional asymmetry introduced by devolution, whereby English mps can no longer vote on aspects of Scottish policy, whereas Scottish mps at Westminster still vote on legislation that will apply to England and Wales alone—is a fully democratic, therefore written, constitution. But this is just what both parties want to avoid at all costs, so increasingly baroque proposals for serial committee stages for ‘English laws’ are being put forward by the Tories, desperate to keep ukip at bay, while Labour refuses to discuss the matter.

Rather than securing a stable future for the uk state, the Scottish independence referendum has ensured the issue will be kept on the table. In 2013, a Westminster Coalition spokesman said that a ‘crushing defeat’ was needed: if 40 per cent or more of the population backed calls for independence, ‘pressure could build’.footnote34 In the absence of that crushing defeat the Labour leadership, seeing housing schemes like Northfield in Aberdeen, Fintry in Dundee, Craigmillar in Edinburgh or Drumchapel in Glasgow awaken to political life, must be recalling the words of that arch-Unionist Sir Walter Scott to Robert Southey, shortly before the Scottish General Strike of 1820: ‘The country is mined beneath our feet.’footnote35 Indeed it is.