Successive mass protests have erupted seemingly out of nowhere since the financial crisis. The Arab uprisings of 2011 were fast followed by mobilizations across the Eurozone periphery, from Greece to Spain, and by Occupy in the us. Anti-corruption sit-ins paralysed Indian cities; Brazil and Turkey erupted in 2013, while counter-mobilizations polarized Ukraine. What social forces and what politics have been in play? Earlier contributions to this journal have analysed the emergence of 21st century ‘oppositional’ strata and examined the confluence of classes in the Brazilian protests—‘new proletarians’, typically telemarketers with degrees, and the inflation-hit middle class.footnote1 In this text, we focus on the social and political character of Turkey’s ‘Gezi’ protests, named after the small park in central Istanbul whose threatened demolition sparked a nationwide uprising that would last for more than a month.

The Gezi protests have already inspired an extensive literature on the causes, form and content of this upsurge. There is a widespread assumption in much of this literature that the protesters were drawn largely from the ‘new middle class’, and that participation from those further down the social scale was either low or non-existent. Turkey’s protest movement has been seen as a manifestation of a new middle-class politics—democratic, environmentalist—whose global import is predicted to grow. Here, we test these assumptions through analysis of four sets of quantitative data: three surveys and a newspaper-based protest dataset. In contrast to many accounts, which concentrate largely on the central core of protesters inside Gezi Park itself, we examine the Turkish uprising at its height, when the greatest numbers were mobilized across the country, and look at levels of passive support as well as activist cadre. In the sections that follow, we briefly outline the arc of the protests, explore the arguments concerning their nature, sketch the broader economic and political context in which they took place and conclude with our own analysis, based on survey and protest data.

Course of the protests

Gezi Park itself is a small area of grass and trees abutting Taksim Square, Istanbul’s social and cultural centre. The akp-dominated Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality had granted permission for it to be turned into a shopping mall, fronted by an ersatz reconstruction of the ornate Ottoman-era Artillery Barracks that had once occupied the site, as part of a broader construction project involving the pedestrianization of Taksim Square. A small group of environmental activists began to organize a campaign in the early months of 2013 and applied unsuccessfully for a court order to stop the work. The destruction of the park began on 27 May 2013, with bulldozers tearing up a small pathway and a number of trees. Activists already present on the site managed to stop further demolition work, and were joined the following day by a larger group of campaigners, including opposition members of the Turkish parliament. Some put up tents in the park, to maintain a vigil overnight. When news spread on social media that these Occupy-style protesters had been brutally attacked by the Istanbul police in the early hours of 29 May, far greater numbers joined them in the park. An aggressive intervention by Prime Minister Erdoğan, declaring that the government would press ahead with the shopping mall, no matter what its opponents said, had a similar effect.

The movement snowballed in response to this repression: the numbers taking part rose from tens to hundreds and then thousands between 27 and 30 May, finally reaching hundreds of thousands on the night of 31 May, as a sea of protesters crowded İstiklal Street and other boulevards around Taksim, building barricades and trying to reach the square itself and Gezi Park, which were then surrounded by police. Protests spread to other parts of Istanbul: thousands managed to cross the Bosphorus Bridge from the Anatolian side, reaching Taksim in the early hours of 1 June. Hundreds of thousands more in other cities followed what was happening in Istanbul through social media and took to the streets in their own localities. Istanbul’s Sixth Administrative Court belatedly granted a stay of execution on the shopping-mall project, but it was already too late to defuse the protests.

Following a night of clashes, during which over a thousand demonstrators were injured, the police withdrew. Barricades were thrown up around the whole area, creating a liberated zone—the Taksim commune—where money didn’t circulate: food, drink and medicines were shared collectively. In the days that followed, an estimated 16 per cent of Istanbul’s population joined the protests, some 1.5 million people. In İzmir, Turkey’s third largest city, the figure was half a million. After police retook the square on 11 June, lower-level protests continued in people’s assemblies and neighbourhood forums—forty in Istanbul alone. The park was saved, though repression continued, as selected activists were sacked, arrested or put on trial.

Interpretations

The first serious analysis of the Gezi events came from the eminent Turkish social scientist, Çağlar Keyder. In a series of interventions, Keyder has argued that the protests are best seen in terms of a newly emerging middle class, dissatisfied with the ‘neo-liberal authoritarianism’ of the ruling akp, taking their demands and aspirations to the streets.footnote2 According to Keyder, the Gezi protesters were predominantly university-educated youth who had benefited from the economic growth and openness to global influences of the past decade:

Turkey now has some 200 universities and more than 4 million university students; 2.5 million new graduates have been added to the population since 2008. These figures portend a new middle class in formation, whose members work in relatively modern workplaces, with leisure time and consumption habits much like their global counterparts. But they also look for new guarantees for their way of life, for their environment, for their right to the city; and they resent violations of their personal and social space.footnote3

Keyder contended that their economic situation sets these new graduates apart from the old middle class and the bourgeoisie, but also from the traditional proletariat. They do not own the means of production, but their cultural capital—education, knowledge, skills—makes them indispensable for the production process; they are paid for mental rather than manual labour. In similar fashion, the political sociologist Cihan Tuğal has emphasized the significant role played by professionals, especially during the early stages of the Gezi protests. From 28 to 31 May, he stressed, as the number of protesters rose from hundreds to thousands, professionals made up the overwhelming majority. According to Tuğal:

Professionals not only led the movement, but also constituted the core of the participants . . . The Gezi Resistance appears to be an occasionally multi-class, but predominantly middle-class movement. Generously paid professionals who have some control over production and services (even though they may not have ownership), rather than white-collar proletarians (such as waitresses, sales-clerks, subordinate office clerks, etc.) seem to predominate.footnote4

This perspective echoed the ‘new class’ concept developed by Alvin Gouldner in the 1970s, whereby a technical intelligentsia armed with ‘cultural capital’ enters into conflict with the ruling class, not because of structural contradictions at the economic level but because of heightened tensions between their subjective and objective situations and aspirations—‘the blockage of their opportunities for upward mobility, the disparity between their income and power, on the one side, and their cultural capital and self-regard, on the other’.footnote5 For Loïc Wacquant, too, Gezi involved ‘a fraction of the Istanbul population, the new cultural bourgeoisie of intellectuals, urban professionals and the urban middle class, rising to assert the rights of cultural capital against an incipient alliance of economic capital—commercial interests—and political capital—the state deciding to transform this park into a mall.’footnote6 He argued that the future of the movement would depend on the kind of relationship that this new urban middle class managed to cultivate with the marginalized urban groups, who were unable to accumulate any kind of capital and were represented very little, if at all, during the Gezi events.

Against this view, one of Turkey’s leading Marxist scholars, Korkut Boratav, saw Gezi as an example of what he calls a ‘mature class uprising’: the protesters were predominantly highly skilled and educated proletarians, whom others have (mistakenly) categorized as part of the new middle class, and students, most of whom he believes to be future proletarians.footnote7 The only exceptions to this were the independent professionals, who might be regarded as belonging to the new middle class, since their livelihood is based on the provision of services to their clients. Boratav agreed that there was considerable support from this layer at the Gezi protests, but saw it as conjunctural and contingent. In his view, Gezi should be understood as a class revolt against the attempts of crony capitalists and their political representatives to appropriate urban space. Likewise, Ahmet Tonak insisted that, in terms of their relationship to the means of production, those who joined the Gezi protests were predominantly workers, potential workers (students), children of workers, unemployed and even retired workers.footnote8 For Michael Hardt, meanwhile, Gezi exemplified the notion of ‘multitude’ by bringing together a range of disorganized subjects and disintegrated conflicts.footnote9 In order to achieve its long-term demands, whatever they may be, it will have to build sustainable relationships among its different constituents. The popular assemblies organized after the Square was cleared could provide only a provisional solution.

Before examining the evidence for and against these claims, it may be helpful to give a quick sketch of the economic and political developments since the neoliberal-Islamist Justice and Welfare Party (akp) dislodged the parties of the Kemalist establishment in 2002. The past twelve years have been a period of breakneck economic growth in Turkey: gnp has expanded from $230bn to $788bn, driven by the akp’s export-oriented free-market strategy and huge inflows of foreign investment. While financialization, land speculation and overseas trade have generated big fortunes for a minority of capitalists and a section of the upper middle class, real wages have declined significantly and the gap between rising manufacturing productivity and wage growth has widened. At the same time, a wave of rural-to-urban migration, starting from the 1990s—with peasants pushed from their land by the elimination of rural subsidies, as well as the internal displacement of more than two million Kurds from the countryside—has accelerated the growth of a vast informal proletariat. By 2011, some 55 per cent of the labour force was working in the informal sector. This dispossessed population has boosted the level of structural poverty in metropolitan areas. A sharp class divide between the globally integrated urban bourgeoisie and upper middle classes, on the one hand, and the growing informal proletariat on the other, has emerged as one of the most important characteristics of contemporary Turkish society.

As Yunus Kaya has shown, these dual processes of proletarianization and polarization have produced the parallel growth of capitalist, professional and proletarian classes, at the expense of the peasantry. In 1980, nearly 54 per cent of the workforce had been engaged in agriculture; by 2005 that figure had fallen to 29 per cent, while 25 per cent were employed in manufacturing—including a significant number of women in the low-tech export sector—and 46 per cent in services. The largest increase by employment category was of routine non-manual workers (administrative, sales, services), whose share of the labour force rose from just over 5 per cent to nearly 13 per cent.footnote10 The massive expansion of tertiary education, to which Keyder refers, has so far yielded little in terms of employment returns: in 2009, nearly 20 per cent of graduates between the ages of 20 and 30 were unemployed.

AKP’s hardening hegemony

The akp has positioned itself within this fast-changing social landscape by claiming to champion the interests of the majoritarian popular classes, while pursuing an orthodox neoliberal, pro-eu, pro-nato line.footnote11 It portrays the Kemalist political establishment—chiefly composed of the Republican People’s Party (chp) and its media outlets—as representing the economic, social and military elite. With the help of a credit-fuelled boom, the akp has been able to establish an unassailable electoral majority through its hegemony over the informal urban proletariat and the rural poor, bolstered by astute clientelist practice. But its pro-Western policies also attracted the support of left-liberal strata, alienated from the Kemalist bloc. By contrast, the chp has mostly relied on an urban middle-class electoral base. The akp’s onslaught against its Kemalist rivals escalated into a regime-wide purge during the 2000s, with the Erdoğan government initiating vast police and juridical operations against its opponents, jailing journalists, academics, politicians and army officers in the infamous Ergenekon trials. The regime juggled temporary tactical alliances with a wide array of different groups, including the tightly organized religious group of Fethullah Gülen, to align against its enemy of the moment: the military, the pkk, some parts of the bourgeoisie, trade unionists and Alevis.

In 2010, the akp pushed through a referendum allowing it to rewrite the constitution (though the most repressive features were retained). The following year, Erdoğan won his third electoral victory, harvesting almost 50 per cent of votes cast. Now with a freer hand, his ‘zero problems’ foreign policy soon pivoted into a dirty war against the Assad regime, rhetorically backed by Sunni chauvinism. The regime became more openly authoritarian and socially conservative. Pressures on organized labour increased, both through privatization and subcontracting, and direct political repression. Legislation was drafted to limit women’s rights, including tightening the law on abortion—legal in Turkey since the 1980s—and informing pregnant women’s families about their condition. Honour killings of women increased fourteen-fold between 2002 and 2009, alongside the killings of transgendered people. The akp also introduced stricter regulation of the sale of alcohol. One result of these moves was to produce a radicalized secularist constituency, whose disappointment with the failure of the mainstream opposition drove them toward militant street activism as the only remaining way of challenging the akp.

This explains why the number of political protests was already rising steadily in the year preceding the Gezi uprising: from fewer than 60 in July 2012 to over a hundred a month from September to December 2012; from 150 in January 2013, to over 200 in March and 250 in May, spiking at over 400 protests in June 2013.footnote12 In the fall of 2012, Kurdish protests—including a 68-day hunger strike that involved thousands of Kurdish prisoners—helped push the akp into peace talks with the pkk after thirty years of armed conflict. Alevis challenged the increasingly sectarian, Sunni-oriented policies of the akp, symbolized by Erdoğan’s naming the new Bosphorus bridge after Yavuz Süleyman, the sixteenth-century Ottoman sultan who had ordered the slaughter of 40,000 Alevis. Protests by feminist groups forced the government to withdraw the new abortion law. Labour militancy rose, with strikes by Turkish Airlines employees and textile workers. lgbt activists took to the streets against hate crimes, while in December 2012 protesting students were beaten back by riot police at the Middle East Technical University in Ankara. Environmental activists campaigned against government proposals to build new hydroelectric and nuclear plants. Secularist chp supporters turned the Republic Day celebrations on 29 October into anti-government protests. Football ‘ultras’, who would be at the heart of the Gezi protests, were increasingly involved in street-fights with the police. Gezi would bring together these different groups on the basis of anti-government sentiment, mobilized, in the face of fierce state violence, around the most innocent of political demands: ‘Don’t demolish our city park’.

Social analysis

Who, then, were the Gezi protesters, in the broadest sense—what was the class composition of the uprising and what ideologies did it espouse? In what follows, we analyse the results of three surveys: two by the konda Research Institute, during and just after the protests in June and July 2013; and one by the samer Research Institute, conducted in Istanbul and İzmir in December 2013.footnote13 We use the samer data to present a fine-grained analysis of the Gezi protesters and their supporters, deploying the class categories developed by Alejandro Portes and Kelly Hoffman: capitalists (proprietors or managing partners of large/medium firms), executives (managers or administrators of large/medium firms or institutions), professionals (university trained, in public service or large/medium firms), petty bourgeoisie (own-account professionals, micro-entrepreneurs), non-manual formal proletariat (vocationally trained salaried technicians, white-collar employees), manual formal proletariat (skilled or unskilled waged workers, with labour contracts) and informal proletariat (non-contractual waged workers, casual vendors, unpaid family workers).footnote14

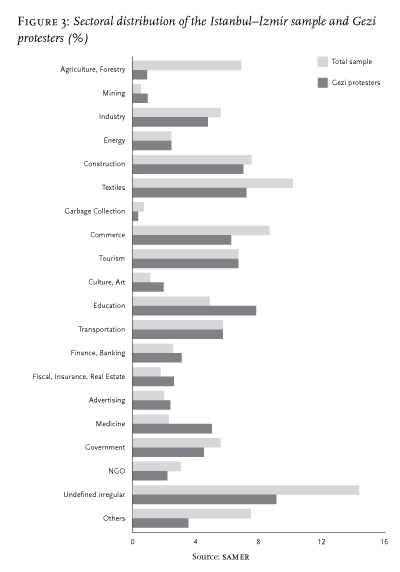

Figure 1 (below) shows the results of our analysis of the social distribution of Gezi protesters and their supporters, compared to the general population for Istanbul and İzmir.footnote15 The largest single group of protesters was from the manual formal proletariat (36 per cent), followed by the non-manual proletariat (20 per cent), the informal proletariat (18 per cent), the petty bourgeoisie (11 per cent), professionals (6 per cent), executives (5 per cent), and capitalists (4 per cent). In other words, more than half of the protesters—approximately 54 per cent—belonged to the formal and informal proletariat, the two lowest echelons of the class structure. Adding the non-manual formal proletarians, i.e. white-collar employees and technicians, increases the proletarian participation rate to 74 per cent. At the same time, the upper classes had a higher representation among Gezi protesters than among the population as a whole: in other words, the likelihood of an individual having participated increased if he or she was from a higher class location. This does not, however, erase the fact that the absolute majority of protesters came from a proletarian background.

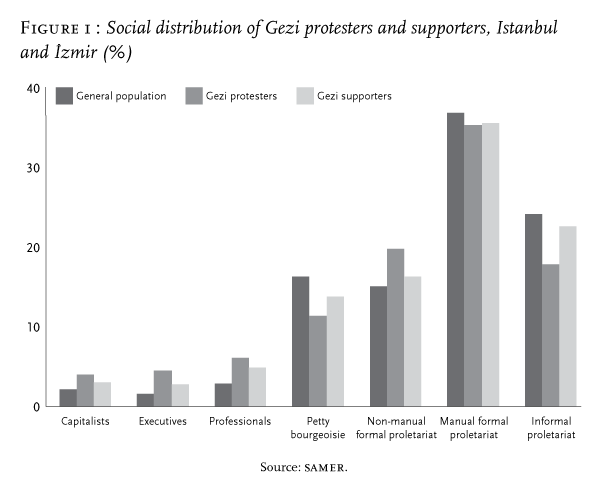

Next, we analysed the proportion of those taking part in or supporting the protests from each social class (Figure 2). Although the rate of participation was much lower among the manual formal proletariat and the informal proletariat, 14 and 12 per cent respectively, they contributed more than half of the total protesters because of their greater numerical strength. (The lower rate of participation may also be related to their limited time and other resources in comparison to the other strata.) The ‘new middle classes’ referred to by many commentators would correspond to the following layers: non-manual formal proletariat (salaried technicians and white-collar employees), professionals (university-trained, salaried professionals in the public service and large or medium-sized private firms), and executives (managers and administrators of large/medium firms and public institutions). Our analysis shows that these strata constituted 31 per cent of Gezi protesters. While this represents a larger proportion than their overall presence in the Istanbul–İzmir sampled population—20 per cent, according to samer—the Gezi protests at their height were not a ‘new middle class’ movement: 54 per cent of participants were proletarians, 11 per cent petty bourgeois and 4 per cent capitalists.

Gezi protesters were thus drawn from a heterogeneous class population. The rate of participation was very high among professionals, executives and capitalists (35–45 per cent) and relatively low among proletarians (12–21 per cent). This helps explain why the protests have been so widely perceived as a ‘new middle class’ uprising. While the majority of protestors came from a lower-class background, the high rate of participation within the middle and upper classes created the impression of a predominantly middle-class crowd. In addition, the middle classes had more control over the means of communication and could therefore represent themselves as a greater social force in the Gezi protests than they actually were.

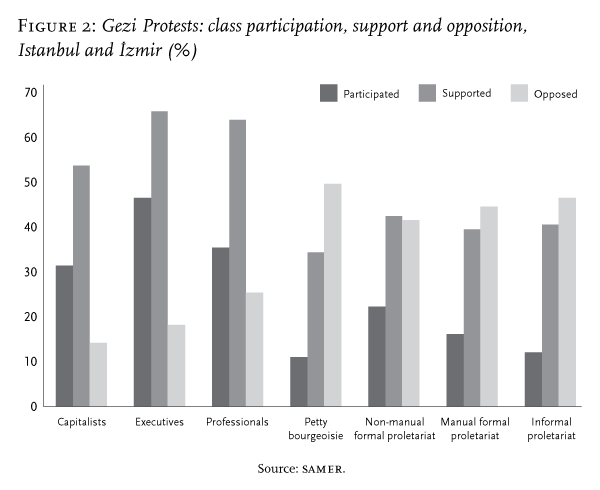

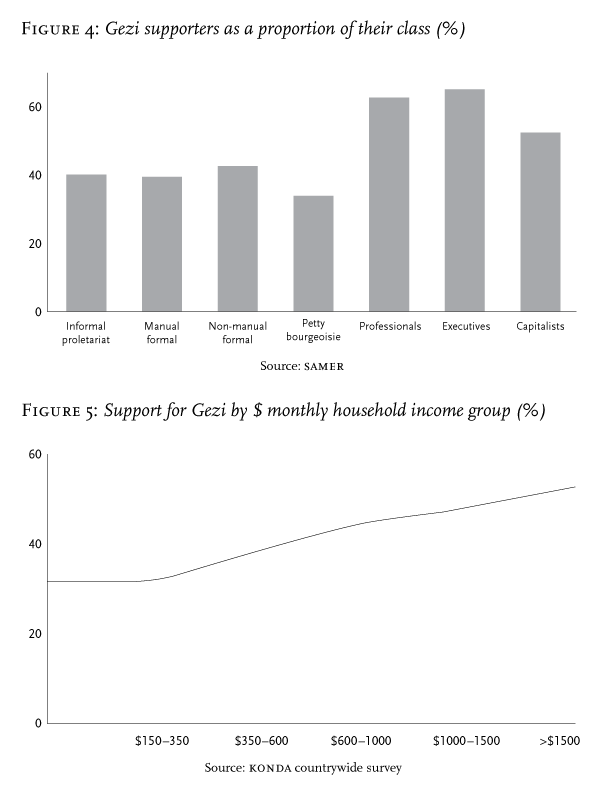

Analysis of income distribution shows that two-thirds of Gezi protesters had a monthly household income below $1,250—only slightly lower than the segment of the total Istanbul–İzmir population whose income falls below that threshold. In terms of employment, the sectoral distribution of Gezi protesters was very similar to that of the broader population in the two cities, although there were slightly more protesters working in medicine and education and slightly fewer in textiles, commerce, agriculture and irregular activities (Figure 3). The same held true for wage distribution: informal and manual-formal proletarian protesters had slightly higher wages than is the case for these layers as a whole, but otherwise Gezi protesters received the same wage levels as the larger sampled population. And despite the public perception that workers were hostile or at least indifferent to the protests, the surveys show that around two-fifths of all proletarians supported Gezi, while among the upper strata this ratio increases to around three-fifths (Figure 4).

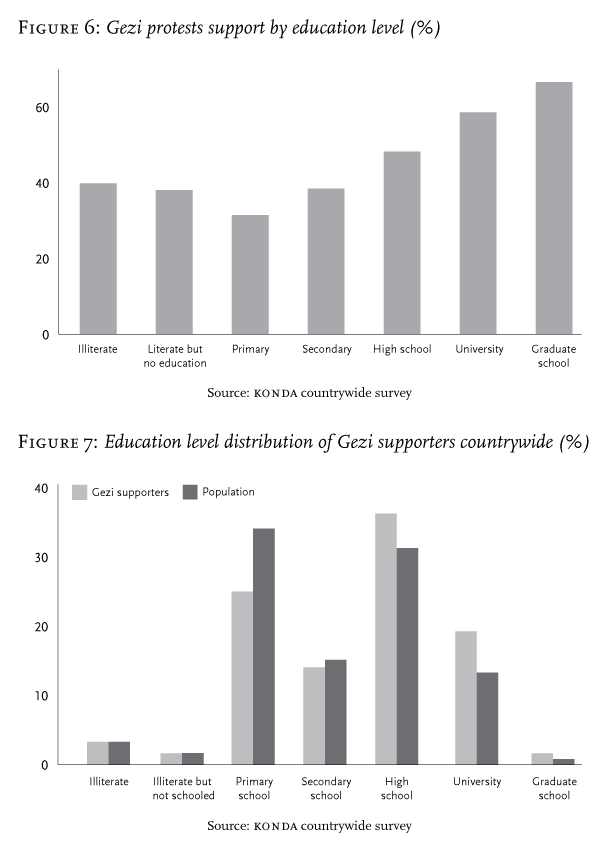

So far we have examined the data from the Istanbul–İzmir survey. Turning now to the second konda survey, we again find that the level of support for Gezi rises among higher income groups (Figure 5). There is a similar correlation with higher levels of education, with a slight decrease among primary school graduates (Figures 6 and 7, below). But, as with the Istanbul–İzmir survey, the fact that support for Gezi rises in parallel to income and education levels does not mean that these higher strata were a majority. On the contrary, the countrywide survey shows that 76 per cent of Gezi supporters in Turkey have monthly household incomes below $1,000—an income distribution which perfectly matches that of the general population.

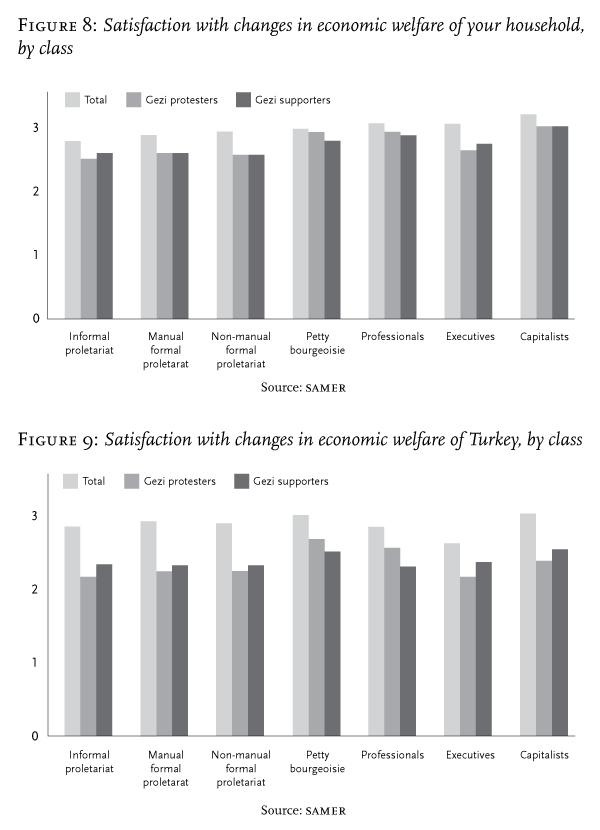

What was the impact of broader economic conditions on the Gezi protesters and supporters? When those in Istanbul and İzmir were asked about the situations of their household and of Turkey as a whole, their evaluations were slightly more pessimistic than the average for their class stratum (Figures 8 and 9). Nevertheless, the difference between the larger sampled population for the cities and the Gezi supporters and protesters remained constant over different social classes, which shows that economic insecurity should be seen as a factor driving not only the ‘new middle classes’ but all other classes as well.

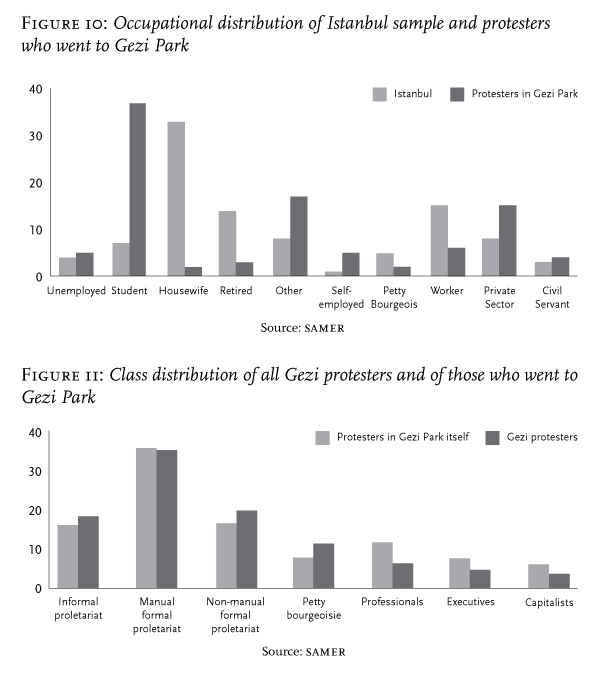

So far, we have demonstrated that ‘Gezi protesters’ in the widest sense were broadly representative of the wider population in class terms. Those who went to Gezi Park itself, however, as opposed to Taksim Square or the other protests, presented a rather more elevated class profile. There were fewer workers, and more professionals and executives, among those who stated that they went to the park during the protests. Relative to the overall Istanbul population, students made up a large proportion of the protesters in Gezi Park, while housewives were notably under-represented (Figure 10). In the park itself, class distribution was skewed slightly upward (Figure 11) as the more organized activists and left-wing groups were mainly concentrated in Taksim Square and the barricaded streets surrounding it, while unaffiliated individuals congregated in Gezi Park and took part in the social activities and performances. According to the konda survey, 79 per cent of those in the park said that they did not belong to any political organization, and 94 per cent said that they came to the park as individuals and not to represent any particular group. For 55 per cent, the Gezi protests were the first political demonstration they had ever joined.

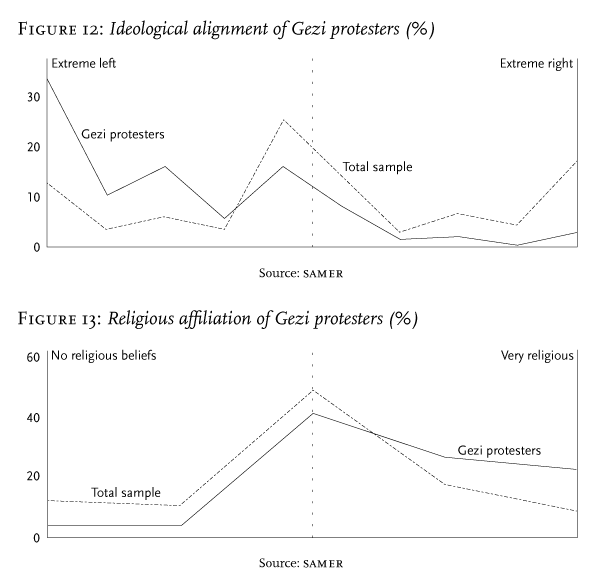

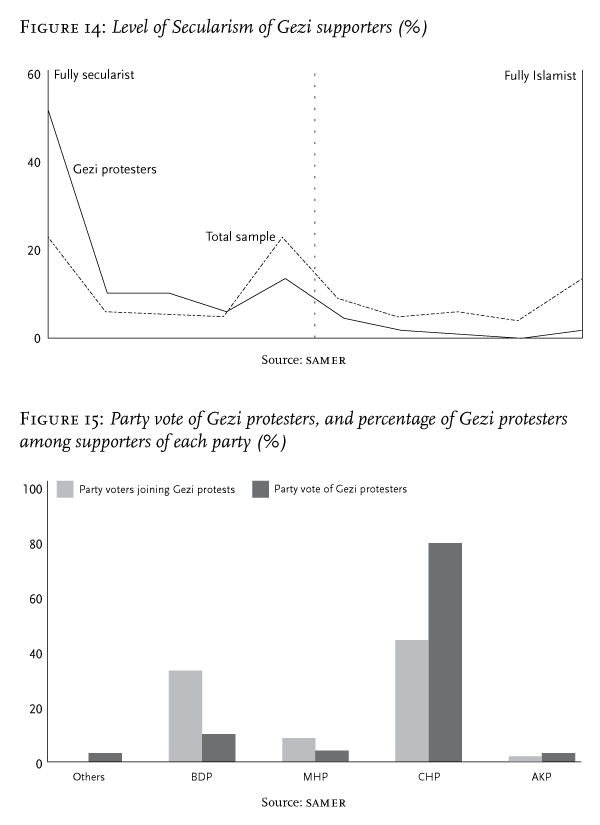

But if all classes were proportionately represented, our analysis shows that Gezi protesters and supporters differed from the rest of society in terms of their political and cultural orientations. While the populations of Istanbul and İzmir tend to cluster on the centre ground, leaning slightly more to the right than to the left, Gezi supporters aligned themselves strongly with the left. In terms of religious beliefs, they were less pious than the general population, although the median number had some religious affiliation (Figures 12 and 13). They differed most significantly from the rest of the population in their view of secularism (Figure 14). In terms of their political alignments, a large majority of Gezi supporters were chp voters, with a smaller group opting for the Kurdish bdp. Although there are slight class variations, approximately 80 per cent of Gezi protesters would vote for the chp, with 10 per cent favouring the bdp. Support for the akp and the far-right, ultra-nationalist mhp was much lower (Figure 15).

What were the subjective motivations of the protesters? According to the konda survey, nearly half—49 per cent—decided to go to Gezi Park after seeing the police violence. The overwhelming majority expressed their demands in terms of anti-authoritarianism and civil rights: ‘for freedom’ (34 per cent), ‘for rights’ (18 per cent), ‘against dictatorship and oppression’ (10 per cent), ‘for democracy’ (8 per cent), ‘against police brutality’ (6 per cent). A fifth of the protesters (19 per cent) had come to the park when the municipality started tearing out the trees. Only 5 per cent of protesters said that their main demand was against ‘the removal of the trees and the replica barracks’. By contrast, according to our data sets for newspaper coverage of protest events in the year prior to Gezi, the dominating issues were of human rights (40 per cent), along with freedom of expression (23 per cent) and workers’ rights (20 per cent). Even though there were a significant number of workers among the Gezi protesters, labour-based claims were not predominant. Some 61 per cent of protesters said they took part ‘as citizens’, while just 5 per cent did so ‘as workers’; the same was true of professionals (the ‘new middle class’).

These findings suggest that the Gezi protests were not a sudden outburst but part of a larger protest cycle, in which the level of political activity had already begun to escalate during the year preceding June 2013. Within this cycle, the protests should not be seen as the movement of any particular social layer, be it ‘the new middle class’ or ‘the proletariat’. Professionals, executives and big proprietors had a slightly higher representation relative to their overall weight in Turkish society, but this does not mean that they constituted the majority of Gezi protesters. On the contrary, most came from white- or blue-collar proletarian backgrounds. The widespread assumption that the ‘new middle classes’ were the main social force behind the Gezi uprising probably derives from the fact that these strata had greater representative power in both social and mainstream media, which made them more publicly visible than other classes. Also, those who were in Gezi Park itself, where media attention was focused, had slightly higher class profiles, which may have contributed to the impression that Gezi protesters in general came from middle-class backgrounds.

Class is therefore not effective as an explanatory variable for the Gezi protesters. What differentiated them was not their class background but their political and cultural orientation. The protests should be understood as a popular movement driven by political demands, in which all social classes participated proportionally. The akp’s authoritarianism and socially conservative policies, together with their brash rebuilding and commercialization of the urban environment, had angered wide layers of the population, ultimately provoking countrywide protests against the government. The demands were predominantly political and embraced all social classes. As such, the main target was not capital and its owners, but the Erdoğan government.

How should the Gezi protests be seen in comparative perspective? Broadly speaking, the revolts since the 2008 financial crisis might fall into three categories. The first, and to date the weakest, would be anti-austerity, anti-neoliberal protests in the crisis-struck capitalist heartlands: Occupy Wall Street, the indignados in Spain, the Greek protests against eu–Troika rule. The second type would be the anti-authoritarian, pro-democracy protests, often triggered by rigged election results, which have erupted across the neo-capitalist former Second World, including the Arab states, Russia and now Hong Kong. (Ukraine might be seen as a combination of the second category—the anti-Yanukovich protests in Kiev—and the first: anti-neoliberal, anti–eu occupations in the Donbass Basin.) Thirdly, there have been mass protests in the other bric countries, notably Brazil and India, characterized since 2008 by inflationary, credit-fuelled expansion, construction booms and new levels of corruption. Here, as in the us and eu, a rapid rise in student numbers has confronted a contraction in secure white-collar jobs, and the precarization of formal as well as informal sectors.footnote16 A new generation has taken to the streets.

At face value, the Gezi protests might seem to fit the third category, especially given the trigger—anger at government-backed commercial construction encroaching on a rare fragment of public green space—and the seeming youth of the protest leaders. But although Gezi shares some characteristics of this category, at least in terms of demands voiced by the protesters, we contend that it fits better into the second category: anti-authoritarian and pro-democracy protests. The alliance of ‘new proletarians’—typically, graduates working in telemarketing—with inflation-hit middle classes, which André Singer has defined as a central feature of the 2013 Brazilian protests,footnote17 does not capture the extent to which ‘old proletarians’ participated in the Turkish events. Again, economic issues—including soaring prices in privatized public goods, such as transport—were crucial in Brazil, whereas in Turkey, the main triggers were political.