After three decades of sustained growth China, an economic powerhouse of continental proportions, is becoming choked by bottlenecks: overcapacity, falling profits, surplus capital, shrinking demand in traditional export markets and scarcity of raw materials. These imbalances have driven Chinese firms and citizens overseas in search of new opportunities, encouraged by Beijing’s ‘going out’ policy. Their presence in Africa has drawn a vast amount of attention, despite the fact that the prc only accounts for a tiny fraction of foreign direct investment there—4 per cent for 2000–10, compared to 84 per cent for the Atlantic powers.footnote1 In the ensuing rhetorical battle, the Western media has created the spectre of a ‘global China’ launching a new scramble for Africa, while Beijing for its part claims simply to be encouraging South–South cooperation, free of hegemonic aspirations or World Bank-style conditions. These seemingly opposed positions, however, share the implicit assumption that Chinese investment is qualitatively different from conventional foreign investment. What, if any, is the peculiarity of Chinese capital in Africa? What are the consequences of China’s presence, and what prospects does it offer for African development?

In exploring the story of ‘China in Zambia’, this text will foreground two issues which are often lost in the debate about ‘global China’. First, outbound Chinese investors have had to climb a steep learning curve in dealing with types of politics not found in their own country. From resource nationalism and adversarial trade unions to the moral condemnation of their work culture, struggles driven by African state and working-class interests have compelled compromises and adjustments on the part of the incoming Chinese. In other words, China’s interests and intentions in Africa have to be distinguished from its capacity to realize them. Second, these contestations have taken place on a terrain already deeply carved by neoliberal reforms imposed by Western financial institutions and donor countries, before the arrival of Chinese investment at the turn of the millennium. Chinese capital, like other foreign capital, has taken advantage of the liberalized labour laws and investor-friendly policies, but has also been challenged by some of the political backlash neoliberalism has generated.

The arguments presented here are drawn from a comparative ethnographic study of Chinese and non-Chinese corporations in two industries, copper and construction. In addition to interviews conducted in Zambian mining townships, government and union offices, I have spent a total of six months over the past five years in copper mines owned by multinationals registered in China, India and Switzerland. The field work included shadowing mine managers, both underground and on the surface, observing production meetings, living among expatriates in company housing and attending collective-bargaining negotiations. With the assistance of the Zambian government, I gained access to the management of the major foreign corporations in mining and construction, as well as trade unions, miners and construction workers. To investigate construction practices, I visited twenty sites run by Chinese, South African and Indian contractors, interviewed over 200 managers and workers, and implemented a questionnaire survey. I also worked with, observed and interviewed government technocrats and politicians on how they handled China–Zambia relations.

The two sectors offer a useful contrast in operational conditions: copper mining is a capital-intensive, place-bound, unionized strategic sector, whereas construction is labour-intensive, foot-loose, non-unionized and non-strategic. And while no single country could be representative of Africa, whose wide range of political-economic conditions and natural endowments defy continent-wide generalizations, Zambia is a critical case for several reasons. Though it undertook one of the fastest privatization programmes in Sub-Saharan Africa, its submission to imf–World Bank neoliberal orthodoxy in the 1990s was entirely typical: newly elected African governments of every ideological colouration were obliged to accept structural adjustment programmes in this period, becoming ‘choiceless democracies, unable to deliver on their electoral promises’.footnote2 Zambia is also Africa’s top copper producer. On the basis of long-standing good diplomatic relations, it has become a leading destination for Chinese state-backed investment and the site of the first Chinese-run Special Economic Zones. As elsewhere in Africa, Chinese contractors have established an unrivalled dominance in construction here.

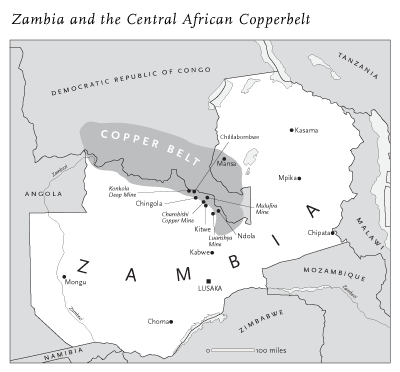

Lying on the southern edge of the Central African copper belt, Zambia has a population of 13 million, concentrated around the capital, Lusaka, and the towns of the copper region. Despite the country’s resource wealth, per capita gdp is only $1,540, and subsistence agriculture is the biggest single employer. Inhabited since the earliest times, the country is home to a range of different Bantu-language groups. The region was subdued—not without a fight—by Rhodes’s British South Africa Company in the 1880s, then ceded to London, which ruled it as Northern Rhodesia. By the 1920s, rich copper deposits were attracting mining financiers from the us, Britain and South Africa; by 1945, its copper exports amounted to 13 per cent of the world total. At independence in 1964 Zambia, led by Kenneth Kaunda’s United National Independence Party, was reckoned a middle-income country with good prospects for full industrialization. Michael Burawoy’s The Colour of Classon the Copper Mines (1972) provides a benchmark reference for the Zambian mining industry in this period, and helps to establish the specificity of the African context that is so often obliterated in current analyses of ‘China in Africa’. Forty years apart, we conducted fieldwork in the same mining towns, both of us examining the inter-relations between foreign investment, the Zambian working class and the state; in the interim, however, the world economy had gone through a sea change. Writing in the tradition of Frantz Fanon, Burawoy was investigating the realignment of class interests in the transition from colonial rule: despite ‘Zambianization’, with the state acquiring a 51 per cent stake in the mines, two Western companies maintained oligopolistic control. Burawoy found that political independence in the context of economic dependence produced a flawed black ruling class, whose interests converged with, rather than challenged, those of foreign capital.

By the mid-70s, the global slump in copper prices had plunged the country into heavy debt and dependency on imf bail-outs, just as the Kaunda government assumed full ownership and management of the mines and instituted an emergency period of one-party rule. The imf’s 1983–87 structural adjustment programme imposed wage freezes in conditions of high inflation, with sharp cuts in food and fertilizer subsidies and government spending. Growing popular and trade-union resistance to austerity culminated in the 1991 election victory of the Movement for Multi-party Democracy (mmd) led by Frederick Chiluba, head of the construction workers’ trade union. Once in office, Chiluba reversed his position to drive through a ferocious programme of imf-backed privatizations—mining, land, transport, energy—and roll back labour rights. While tax revenue from copper had accounted for 59 per cent of government income in the 1960s, by the early 2000s it brought in an astonishingly anaemic 5 per cent, due to the extraordinarily investor-friendly development agreements signed with foreign companies after the mines were privatized.

Yet under conditions of ‘dual liberalization’—the political shift to formal multi-party democracy occurring in conjunction with the economic shift to privatization and foreign investment—these imf–World Bank measures were confronted by the rise of a new oppositional politics of ‘resource nationalism’, in Africa as in Latin America, demanding that the people receive a greater share of the country’s foreign-owned natural wealth.footnote3 As neoliberal programmes decimated the bargaining power of organized labour, elections became the main channel for popular discontents about labour exploitation, lack of social development and corrupt government sell-offs of national resources to foreign investors. The veteran Zambian politician Michael Sata—governor of Lusaka in the 1980s, a minister in Chiluba’s mmd government in the 90s, and founder of his own party, the Patriotic Front, in the early 2000s—ran on a pro-poor ‘Zambia for Zambians’, resource-nationalism platform, attacking the mmd government for selling out to foreign interests and accusing China of imposing slavery from Cape Town to Cairo. Chinese state-owned enterprises were a particular target, for they were seen as representing a foreign sovereign state, not just private investors.