Interview

Ever since the collapse of the ussr, Ukraine has stood out among post-Soviet states in having a much more open, contested political landscape. Why has the country been an exception to the regional norm?

I wouldn’t claim that Ukraine is more of a democracy than the other countries—better to say it’s a more competitive authoritarian regime. The political system that emerged in Ukraine was from the outset more pluralistic than those of, say, Russia, Kazakhstan or Belarus. One of the main reasons for this was the country’s cultural diversity: there were very significant regional differences between the east and the west, and these were reflected in electoral outcomes from the 1990s onwards. Any candidate who won the presidential elections would not be seen as legitimate by almost half the population, who would immediately voice strong opposition to him. The strength of regional identities also tended to politicize socio-economic questions very quickly. This was one reason why the neoliberal reforms were not carried out as rapidly as in Russia, for example—the political forces behind them were unable to build up the same kind of momentum. The difference is also apparent in Ukraine’s constitutional system, which was much less presidential than those of the other post-Soviet states. In Russia, 1993 was clearly a crucial moment, when Yeltsin imposed his will on parliament by force, sending the army into Moscow. Nothing like this happened in Ukraine. The 1996 constitution, approved under Kuchma, gave the president more powers than parliament, but not to the same extent as in Russia: it was a presidential–parliamentary republic, rather than a purely presidential one. This was also a very important factor in the evolution of the political system: presidential elections were not winner-takes-all contests to the same extent as in many other former Soviet countries.

How would you characterize the first post-Soviet governments of Ukraine?

None of them were full-scale authoritarian; it was definitely not a dictatorial state. In the late Kuchma period, the presidential administration would send broadcasters recommended topics for their news programmes, but it’s unclear to what extent this was implemented; there was no direct censorship. The real problem for freedom of speech has been that the majority of the tv, radio and press are privately owned. In that sense it has worked more along Western lines, where the media corporations advance the political agendas of their owners. Economically, you could say that Kuchma, and later Yanukovych, played the role of a kind of protectionist state for Ukrainian capital. With the state’s assistance, figures like Rinat Akhmetov, Ihor Kolomoyskyi and Viktor Pinchuk acquired old Soviet industries at fire-sale prices, and then made huge fortunes not so much by investing or upgrading as by using them to make quick money, shifting their capital to Cyprus or other offshore havens. For many years, Kuchma and Yanukovych were also able to balance on the question of whether to integrate into Europe’s economic sphere or Russia’s, moving neither to the West nor the East. This shielded Ukraine’s oligarchs, preventing them from being swallowed by stronger Russian or European competitors. It’s worth pointing out, too, that the oligarchs were able to play a different role in the political system from their Russian counterparts: here the state was unable to dominate them and exclude them from participation as Putin did.

Why was the 1990s economic downturn so much worse in Ukraine than elsewhere?

One of the most important factors was that Russia had natural resources—oil and gas—which Ukraine did not; hence they were able to maintain living standards at least a little better. Ukraine had a lot of plant in high-tech sectors—aviation, cybernetics, the space industry—which suffered especially from the ussr’s collapse. Much of the country’s machine-building and engineering industries also went down when they lost their connections with the former Soviet republics, and what remained was not so competitive compared to Western European production. The 1990s was a period of severe industrial decline in Ukraine. Some people, including many on the left, think that it’s still a developed industrial country. I very much disagree, because although metallurgy, which accounts for a major part of its exports, entails some processing—producing rolled steel from ores, for example—it doesn’t involve a high level of value added. Still, the rise in commodity prices in the 2000s meant that there was something of a recovery, mainly concentrated in the east, and mainly in metallurgy. But the slight growth was very unevenly distributed, bringing greater inequality.

How would you describe the outcomes of the Orange Revolution of 2004?

It was a change of elites rather than a revolution: it didn’t create the potential for radical structural and institutional change. One of the reasons it was resolved so quickly—it was over in three weeks—was that a deal was made within the elite. Kuchma agreed to surrender and to stop backing Yanukovych in exchange for revisions to the constitution, diminishing the powers of the president so that Yushchenko would not be winning so much. You could say that after 2004, the system went from being presidential–parliamentary to parliamentary–presidential. The electoral system was also changed to give more control to the party leaderships. Before 2004, half the Rada was elected from party lists, half from majoritarian districts. After the Orange Revolution the system was based exclusively on party lists, with no mechanism of popular control over who got included on them. The party leaderships had tremendous power—they could exclude any dissenting mps and automatically replace them with another person from the party list. Partly as a result of all this, Yushchenko ended up being a very weak president, counterbalanced by a premier with a strong parliamentary base—Tymoshenko and Yanukovych each held the post for a time. But Yushchenko’s weakness was also partly down to his own decisions: he did almost nothing on the economy, and towards the end totally devoted himself to the nationalist agenda—focusing on things like making Stepan Bandera a national hero, and commemorating the Holodomor, the great famine of 1932–33, as an ethnic genocide of the Ukrainian nation by the Communists. By the end he had completely alienated his electorate, scoring only 5 per cent in the 2010 presidential elections.

Unable to steal the elections in 2004, Yanukovych won in 2010, defeating Tymoshenko in a run-off. How would you sum up his presidency prior to the protests of late 2013?

One of the first things Yanukovych did was to increase the president’s powers again, securing a decision from the constitutional court to annul the 2004 amendments and go back to the 1996 constitution. This also meant half the Rada mps would be elected in first-past-the-post constituencies again, and half from party lists. As well as attempting to monopolize political power, Yanukovych tried to concentrate financial and economic power around his own team, especially his family. The result was a tremendous amount of personalized corruption—visible in the luxury of his former residence at Mezhyhirya. On the economic front, by the time he took office Ukraine had already been hit hard by the global crisis: there was a slump in prices for Ukrainian-produced goods, especially metals. The hryvnia was devalued by half in late 2008, a number of large enterprises shut down and unemployment rose; small business was suffering too. In 2010 Yanukovych started to introduce austerity measures, which of course quickly proved unpopular. In some cases—for example an increase in taxes on small businesses—the reforms had actually been demanded by the imf, but since half the population already distrusted Yanukovych, for reasons mentioned earlier, he received all the blame. The underlying problem was that the basic social standards which enabled most of the population to survive were deteriorating, and he was unable to find a way to maintain them.

Yanukovych’s announcement on 21 November 2013 that he would be suspending negotiations on the EU Association Agreement was the initial trigger for the protests that eventually led to his downfall. Before we address the unfolding of the crisis itself, can we ask what your assessment of the EU Agreement was?

I would say that Yanukovych actually made the correct decision in suspending it. Now the new government has split the political components from the economic ones, but there were no such discussions in 2013. Not many of Ukraine’s industries would gain from the free-trade provisions—it would mean intensified competition for them, and the loss of many jobs. The terms of the imf credit that the government was negotiating at the same time also played a role: the imf demanded a rise in gas consumption prices for the population, wage freezes and significant budget cuts, all of which would be a blow for the poor classes of Ukraine. Not so much for the middle classes; defined mainly by consumption levels, these amount to no more than 10–15 per cent of the population, and are concentrated in the biggest cities, working either for our oligarchs’ industries or in the offices of Western corporations. At the same time, it’s worth recalling that Yanukovych suspended the agreement rather than rejecting closer ties with the eu outright—European integration was one of his own policies, and what mobilized people was that he made this very radical U-turn. The people who came out onto the streets in November were protesting in support of the government’s original policy—that was the irony.

What was the balance of views on the Agreement within the population as a whole?

According to polls from November, Ukraine was quite evenly split about this—40 per cent were in favour of signing the Association Agreement and 40 per cent supported an agreement with the Russian-led Eurasian Customs Union. Some people supported both—it was not an either/or question for them. Other people were against both agreements. So when the protests began it was definitely not a nationwide people’s revolt.

The first demonstration was reportedly called by the Afghan-Ukrainian journalist Mustafa Nayem in response to Yanukovych’s U-turn, and the movement then swelled over the following days. How would you describe this initial phase of the Maidan protests?

In the beginning the movement mostly consisted of middle-class Kievans and students, who were mainly driven by a European ideology—a ‘European dream’, offering the hope of some kind of breakthrough to a better society. It wasn’t especially conscious or thought through; but then, as utopian thinking it needn’t have much connection to reality to move people. There was also a strong anti-Russian, nationalist component. From the beginning, the Maidan protests posed the choice between the eu Association Agreement and the Customs Union in very stark, almost civilizational terms: is Ukraine with Europe or with Russia, is it going to line up with Putin, Lukashenko and Nazarbaev or have nothing to do with them?

The first gatherings were by no means small: in Kiev on 24 November, a Sunday, there were something like 50,000–60,000 people—one of the largest rallies in recent years. Protests also sprang up in other cities—Lviv, Odessa, Dnipropetrovsk, as well as in the east and south, though they were much smaller there than in the west. In Kiev, for the first few days there were in fact two separate actions—a ‘civic Maidan’ and a ‘party Maidan’—but they soon merged. The parties involved were the opposition to Yanukovych in parliament: Tymoshenko’s Batkivshchyna (‘Fatherland’); udar, which is Vitali Klitschko’s party; and Svoboda, the far-right party. Among these, only Svoboda can be regarded as a real, grassroots force with strong local cells. Tymoshenko’s party and udar are more like electoral machines, designed to bring certain people to power. They revolve around the leader and their teams rather than any ideology. I couldn’t say, for example, what Klitschko’s political views are. The ‘civic’ part of Maidan, meanwhile, was very different from Occupy or the indignados—it was pro-neoliberal, pro-nationalist in orientation.

What was your own relationship to this stage of the Maidan protests?

At first, I was very sceptical, especially when it was so purely a ‘Euromaidan’—I couldn’t be so uncritical of the eu. There were some on the Ukrainian left who joined in the protests with banners saying that Europe also means strong trade unions, quality education, access to public health, equality. I was dubious about this, to say the least—the eu has precisely been destroying the welfare states established in previous decades, and as for equality, what about all the migrants who die while attempting to get into the Schengen Zone? Like many others, I also saw that a free-trade area with the eu could be a dangerous thing for Ukraine. But then, when the attempt at a crackdown took place in the early morning of 30 November, the character of the protests changed—this was now a movement against police brutality and against the government; though it never distanced itself from the Europe question, or from nationalist and other issues that are divisive for Ukrainian society, which proved disastrous later.

This clearly marked the start of a second phase in the protests. Where did the order to attack the Maidan camp that night originate?

It’s still not known who actually gave the order. I’m not sure it was Yanukovych—it would have been so irrational for him to do this, when the protest was already dying out; by the time they tried to disperse the tent camp there were something like 300 or 400 students and rightist activists staying on Independence Square overnight. Of course, Yanukovych made many mistakes afterwards, so it could simply have been another one. Some have speculated that Putin insisted he close down the camp, but this doesn’t seem very rational either. What is also strange is how the attempted dispersal of the protest was depicted by the major Ukrainian tv channels, owned by the oligarchs. Usually their coverage was supportive of the government and critical of its opponents, but the next day the reports shown on the major stations were very sympathetic to the protesters. In some conspiracy theories, the shift was the work of Serhiy Lyovochkin, the head of the presidential administration. He is seen as connected to the metals oligarch Dmytro Firtash, one of the few people from the national bourgeoisie who might actually be interested in European integration—the idea being that Lyovochkin ordered the attack with a view to escalating events.

Either way, the attack and the media coverage of it played a huge role in mobilizing people. The protest held in Kiev on 1 December was enormous. The opposition of course overstated the figure, saying there were up to 2 million people—which is just impossible, there’s not enough space. Some more or less independent evaluations put it at a maximum of 200,000. Still, this compared with the size of the rallies during the Orange Revolution. The movement also spread geographically: there were Maidans in almost every city, although in western Ukraine there was not much political sense in doing this—the local authorities there were from the opposition, so there was nobody to protest against. In the first days of December, people started to build barricades in the centre of Kiev, and the protesters moved in and occupied administrative buildings. The far right were quite active in these occupations—they led the seizure of the City State Administration building on Khreshchatyk, the main street in Kiev, and established their headquarters there. It was also far-rightists who attacked the presidential administration on 1 December; there were violent clashes with riot police for several hours, resulting in hundreds of people being injured. The opposition quickly distanced themselves from the attack, saying it had been carried out by provocateurs. It’s possible that government agents started the violence, but videos of the events showed that the mass of attackers were people from Right Sector. They had already organized themselves into self-defence units, and were training quite openly on the streets, so they had prepared themselves for violence before it started.

Did the far-right groups now active in Ukraine—Svoboda, Right Sector, Trident—have some kind of clandestine existence under Soviet rule?

No, they emerged after 1991. There were some diaspora nationalist groups in the West who went back to independent Ukraine in 1991–92, but they weren’t successful. Svoboda was originally founded in 1991 as the Social-National Party of Ukraine—a none-too-subtle reference to National Socialism—and borrowed a lot from the legacy of Ukrainian nationalism, but at the same time tried to draw on the experience of West European far-right movements like the Front National. Right Sector is a recent phenomenon, it emerged as an umbrella coalition of various far-right groups. Some of them are overt neo-Nazis—for example, Patriot of Ukraine, which uses the Wolfsangel symbol, is unambiguously racist: it was involved in arson attacks on migrant hostels. Right Sector also includes the Social-National Assembly and the Ukrainian National Assembly–Ukrainian National Self-Defence (una–unso). The major group in Right Sector, Trident—Tryzub, in Ukrainian—is not neo-Nazi, but they are certainly far-right, radical nationalists. It would be too soft to call them just national conservatives, as some experts do—including Anton Shekhovtsov, who is quite active in English-language analysis of the far right in Ukraine. Right Sector has now been registered as a political party.

Are these groups connected to the church?

No, I wouldn’t say so, although they promote Christian values—they are against lgbt rights, they say the traditional family is in danger, and so on. The Orthodox Church itself is split in Ukraine: when the country became independent there was a division between the Church of the Kiev Patriarchate and the Church of the Moscow Patriarchate. As far as I know, there are no significant doctrinal differences between the two—it’s a political issue, a symbolic issue. There are also the Greek Catholics, from the Uniate Church, mostly in the former Polish part of Ukraine. As a social force, the churches are more powerful in western Ukraine—these are rural areas with strong patriarchal traditions, and nationalist sentiment runs deep there. Both the Kiev Patriarchate Church and the Greek Catholics were in opposition to Yanukovych, while the Moscow Patriarchate Church supported him. But I wouldn’t say the churches played much of a political role in the Maidan movement, though priests were often present in the square itself.

How would you weigh the contribution of the far right to the Maidan—in terms of numerical presence and ideological impact?

This whole discussion was very difficult for the Maidan’s liberal supporters: to gain Western backing, the protests had to be presented as peaceful, democratic and so on. This was the message in the letter of support signed by many Western intellectuals in early January.footnote1 So there was a real interest in downplaying the far right’s role or else refusing to recognize it altogether. Naturally, it would have been insane to claim that several hundred thousand neo-Nazis had come onto the streets of Kiev. In reality, only a tiny minority of the protesters at the rallies were from the far right. But in the tent camp on Independence Square they were not such a small group, when you consider that only a few thousand people were staying there permanently. More importantly, they had the force of an organized minority: they had a clear ideology, they operated efficiently, established their own ‘hundreds’ within the self-defence structures. They also succeeded in mainstreaming their slogans: ‘Glory to Ukraine’, ‘Glory to the Heroes’, ‘Death to the Enemies’, ‘Ukraine Above Everything’—an adaptation of Deutschland über Alles. Before Euromaidan, these were used only in the nationalist subculture; now they became commonplace. Probably everyone who used the central metro station in Kiev in December witnessed a scene like this: a group of nationalists starts to chant ‘Glory to the Nation! Glory to Ukraine!’, and random passers-by on their way to work or to their studies chant back: ‘Yeah, Glory to the Heroes! Death to the Enemies!’ Everyone now knew how to respond, what was expected of them.

Of course, not everyone chanting ‘Glory to the Heroes!’ was a far-right sympathizer—far from it. The majority chose to interpret the slogans a certain way, as referring not to the heroes of Bandera’s Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, but to the heroes of Maidan. Still, this was a real success for the far right, something neither the liberals nor the small numbers of leftists who took part were able to achieve. Why these slogans rather than other, not so questionable ones? Why not some socio-economic demands? It shows who was actually hegemonic in the process. Numerically, yes, the far right had a minor presence, but they were dominant on the political and ideological level.

What role did the Ukrainian intelligentsia and cultural elite play in the protests?

They were probably more significant in the early stages, the Euromaidan phase, rather than later, when it became a real mass movement. Liberals and progressives tended to support the Maidan, but adopted this rhetorical strategy of downplaying the role of the far right, claiming it was being exaggerated by Russian propaganda. They would criticize Svoboda, for example when it held a mass torchlight march on Bandera’s birthday on 1 January, which was bad for the movement’s image. But they never moved to dissociate the Maidan from those parties. This was a real mistake: by drawing a line between themselves and the far right, they could have put forward something like a bourgeois-democratic agenda—for strong civil rights, no police abuse, against corruption and so on—which eastern Ukrainians could easily have supported too. Instead what emerged was a murky amalgam of various political forces, with very weakly articulated social and economic concerns, in which right-wing ideas and discourse predominated. Part of the reason why the intelligentsia didn’t take a distance from the far right may have been that they knew they were objectively very weak, and thought that dissociating themselves from Svoboda and Right Sector would mean being sidelined from the movement altogether; the alliance was too important to them. But at the same time, this failure prevented the movement from gaining truly nationwide support.

How do you explain the fact that the ideological materials used for the construction of Ukrainian nationalism are all highly reactionary—Pavlo Skoropadsky, Symon Petliura, Stepan Bandera? Have there been any attempts at an alternative, left-wing version that would draw on the populist or anarchist legacies of figures like Mykhailo Drahomanov or even Nestor Makhno?

Yes, Ukrainian nationalism now mostly has these right-wing connotations, and the emphasis on the figures you mentioned has clearly overpowered the leftist strands. But when it emerged in the late nineteenth century, Ukrainian nationalism was predominantly a leftist, even socialist movement. The first person to call for an independent Ukrainian state was a Marxist, Yulian Bachinsky, who wrote a book called Ukraina Irredenta in 1895, and there were many others writing from Marxist positions in the early twentieth century. But any attempts to revitalize socialist ideas within Ukrainian nationalism today have been very marginal. Part of the problem is that it’s not so easy to reactualize these ideas: the people in question were writing for an overwhelmingly agrarian country—something like 80 per cent of Ukrainians were peasants. The fact that the working class here was not Ukrainian was, as we know, a huge problem for the Bolsheviks, intensifying the dynamics of the Civil War in 1918–21, because it was not just a class war, but also a national war; petty bourgeois pro-Ukrainian forces were able to mobilize these national feelings against a working-class movement that was seen as pro-Russian. Today, of course, Ukraine is no longer an agrarian country but an industrialized one, and since roughly half the population speaks Ukrainian and half Russian, it is no longer so easy to say who is the oppressed nation and who is the oppressor.

Then there is the fact that the right has worked to reinterpret figures such as Makhno along nationalist lines—not as an anarchist, but as another Ukrainian who fought against communism. In their eyes communism was a Russian imposition, and anarchism too is depicted as ‘anti-Ukrainian’. At the Maidan, the far right forced out a group of anarchists who tried to organize their own ‘hundred’ within the self-defence structures. They also physically attacked leftists and trade unionists who came to distribute leaflets in support of the Maidan—one of the speakers on stage pointed them out, saying they were communists, and a rightist mob surrounded and beat them.

Were there many such incidents during the protests?

There was much talk of attacks on synagogues in Kiev, but this was probably done by government provocateurs rather than Maidan activists—on the whole there was no serious problem of ethnically motivated hate crimes. There were actually some Jewish hundreds in the self-defence structures—a fact cited by Maidan supporters to show that the movement was not xenophobic or anti-Semitic. There was also a women’s hundred, as well as an interesting initiative called ‘Half of Maidan’, started by some feminists who tried to raise questions of gender equality there. But there were also a few almost medieval scenes on the Maidan—for example they had this ‘stool of shame’, where some alleged thieves were made to stand with the word ‘thief’ written on their foreheads and undergo a process of public humiliation. Another dark side of the Maidan were the so-called ‘titushka hunts’. Titushki are poor, often unemployed youths whom the government used to hire as provocateurs and street bullies—to harass or attack protesters, often in cooperation with the police. Among some of the middle-class Maidan protesters, there was a kind of social chauvinism towards these people. AutoMaidan was a part of the movement that carried out actions using convoys of cars—they’d block streets, make noise outside Yanukovych’s residence or the house of Pshonka, the prosecutor-general. At one point they organized titushka hunts, driving round Kiev looking for them, capturing them and forcing them to make a public confession. But how did they define who was a titushka and who was not? Often it was based on what they looked like, whether they were wearing a tracksuit, these kinds of social markers.

Would it be fair to say that the Maidan didn’t pose an immediate threat to Yanukovych until mid-January?

Each Sunday there would be rallies in the centre of Kiev, and tens of thousands of people would come and listen to politicians and other speakers. But the movement was beginning to stagnate: they didn’t have a strategy for toppling Yanukovych. In the first half of January, fewer people were coming out onto the streets. People wanted progress in the campaign, they wanted some action. Once again Yanukovych handed them the opportunity, when his government passed a package of ten repressive laws on 16 January. They were called ‘turbo-laws’ in Ukraine, because the parliament passed them in barely more than an hour. Some were measures they had tried to bring in before—a law on extremism, restrictions on freedom of assembly and free speech, an ngo law requiring Western-funded organizations to declare themselves as foreign agents. Others clearly targeted actions the Maidan had carried out: a ban on the use of masks, as well as a law banning the formation of columns of more than five cars, directed against the AutoMaidan activists. After this, people started demanding more decisive steps against Yanukovych. But when a crowd gathered to protest the laws on 19 January, the opposition parties didn’t provide any convincing plan of action. So one of the leaders of AutoMaidan, Serhiy Koba, came to the stage and called on the crowd to march on parliament via Hrushevskoho Street, where clashes with police began afterwards. At this point, when the level of violence rose, the rallies and meetings became much less important.

Did the social and regional composition of the Maidan protests change from one phase to the next?

There were surveys done by sociologists in late January about this, which showed that after the violence started on 19 January, the people on the Maidan were less affluent, less educated than in the early stages. They were less likely to come from Kiev, and more from small towns in central and western Ukraine, which is a much less urbanized part of the country—something like 40–50 per cent live in cities and towns, compared to more than 90 in Donetsk province. These regions are mainly poor, they have very serious problems with unemployment—they lost a lot of industrial jobs in electronics, machine engineering and so on after 1991. Many people there survive only because of their private plots, and the few who have stable work are very badly paid. There are many migrants from these regions to the bigger cities in Ukraine, and large numbers go illegally to the eu—to Spain, Portugal, Poland, Italy—to work in construction, cleaning, nursing. It’s hard to get any solid figures for this, but there are estimates putting the number of migrants anywhere between 1 and 7 million. People from these regions are obviously very much in favour of European integration, of being allowed to go to the West freely and work there. They also had clear social grievances against Yanukovych, and not much holding them back—that’s why they were prepared to join the Maidan self-defence forces and go up against the police. The sociologists started calling the tent camp the ‘Sich’, after the Cossack military encampments, but it could be said that the Maidan was to some extent a movement of dispossessed workers.

From mid-January onwards, the protests seemed to enter a third phase, with negotiations between the government and opposition continuing even as violence was escalating, right up to Yanukovych’s ouster on 22 February. What was at stake in these discussions, and what forced the pace of events?

One of the issues for the protesters was for those arrested during the clashes—there were over 200 of them—to be released and amnestied unconditionally; the government insisted that the protesters first vacate the buildings they had occupied. A compromise was eventually reached on this with Pshonka, the prosecutor-general. But the main point was to reverse the 16 January laws, which the parliament also eventually agreed to do. The opposition parties, meanwhile, demanded that the 2004 constitution be reinstated immediately, to give more powers to the parliament. Yanukovych was apparently ready to discuss a new constitution, but would not agree to revert to the 2004 variant—he wanted to create a constitutional commission, to take a long legal route to delay it as much as possible. On 18 February, when the parliament had planned to vote on the change to the constitution, the chairman of the Rada—Volodymyr Rybak of the Party of Regions—refused to allow the bill to be registered. A crowd had come to the parliament to voice support for the opposition, in what had been called a ‘Peaceful Offensive’, but they became very angry when even a discussion of the constitutional change was blocked. Violence flared up again, the police responding especially brutally: a number of people were killed by armed riot police.

Perhaps the major turning point was the shooting of protesters in the centre of Kiev by snipers on 18, 19 and 20 February. Who was responsible for this?

This is an important question—who were these snipers, who gave them orders to shoot to kill? We still don’t know. Some point to evidence that the snipers were shooting both at protesters and police to argue that there was some third force trying to escalate events. There was also a leaked conversation between the Estonian Foreign Minister and the eu’s Catherine Ashton suggesting that some believed the snipers were under the control of the opposition. It was a crucial event, which resulted in a lot of deaths: some 40–50 people were killed on 20 February alone, many of them by the snipers. There was another important development on 18 February in the west of Ukraine, where protesters started to attack police stations and raid their arsenals, getting hold of guns in large quantities. This happened in Lviv, in Ternopil, in Ivano-Frankivsk, in many areas. It changed the situation drastically: the riot police were ready to disperse protesters when the latter were armed with sticks, stones and Molotov cocktails, but they were not ready to die for Yanukovych. After 18 February, the western parts of Ukraine were under the control of the protesters, who occupied the administrative buildings, police and security service headquarters. In some places the police shot at protesters, but in many areas they left without offering much resistance. This was one of the flaws of the regime—it was mainly based on networks of corruption rather than on strong ideological loyalties. Another factor was of course the imposition of European sanctions—the escalation of government repression definitely pushed Brussels into doing this more quickly. After 18 February, the ruling Party of Regions faction in parliament quickly began to dissolve, and many deputies joined the opposition. This transformed the balance of forces in the Rada: there was now an oppositional majority, which could vote for a return to the 2004 constitution and call for Yanukovych’s resignation. In a sense this was the moment when the seizure of power became final. And of course the shootings hardened the resolve of the people in the streets.

What was the relationship between the protesters and the opposition parties at this point?

The opposition parties were much more moderate than the people in the street. They tried to convince the Maidan that compromise with Yanukovych was necessary. For example on 20–21 February, the opposition leaders—Klitschko from udar, Arseniy Yatseniuk from Batkivshchyna, Oleh Tyahnybok from Svoboda—reached an agreement with Yanukovych, mediated by the French, German and Polish foreign ministers: there would be elections in December, the constitution of 2004 would be reinstated in 24 hours, the police withdrawn from central Kiev. The Polish foreign minister, Radosław Sikorski, came to the Maidan Council, a body dominated by opposition politicians, and said: ‘If you don’t agree to this compromise, you will all be dead.’ The Council supported the compromise, but when they announced it to the crowd on the square, it wasn’t accepted. One of the members of the self-defence forces—a 26-year-old from Lviv called Volodymyr Parasiuk—then came to the stage and said that if Yanukovych didn’t resign by 10 a.m. the next day, they would start to take government buildings in Kiev. This the crowd did support. A few hours after that, Yanukovych fled the capital. As footage from security cameras at his residence in Mezhyhirya later proved, he had started to pack his things as early as 19 February—which means that the opposition and European ministers were convincing protesters to agree on a compromise with Yanukovych even as he was preparing his escape from Kiev.

How would you describe the interim government that then took power?

I don’t agree with the idea that this was a fascist coup. The word ‘coup’ implies that there was some well-organized, armed seizure of power planned from above, and that was not what happened. The far right were certainly prominent in the new government: the interim president, prime minister and several other ministers were from Tymoshenko’s party, but Svoboda had four cabinet positions—deputy prime minister, minister of defence, minister of agriculture, minister of the environment—plus the prosecutor-generalship. There were also several people not from Svoboda but with a far-right background: Serhiy Kvit, the education minister, was formerly a middle-ranking officer in Trident, though he probably left many years ago; Andriy Parubiy, the head of the National Security and Defence Council, was one of the founders of the Social-National Party, and led their paramilitary youth wing, Patriot of Ukraine, before joining Batkivshchyna. He was also commander of the Maidan self-defence groups. Or there’s Tetiana Chornovol, a journalist who was kidnapped from the Maidan by the authorities and beaten severely in December—she used to be press secretary of the far-right una–unso, and became head of the National Anti-Corruption Committee in March. But the government is better characterized as neoliberal than far-right. Their economic programme was essentially one of austerity measures: they accepted all the credit conditions imposed by the imf—increasing public utility tariffs, freezing wages, cutting a whole range of benefits. It was a programme that would put the burden of the economic crisis on the poor.

From that point of view, the Russian annexation of Crimea happened at a very opportune moment for the new government, because it helped give it national legitimacy, pushing social issues into the background and uniting people against foreign intervention. Some people began to volunteer for the army and the newly established National Guard, and there were mass rallies in support of the country’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. At the same time, Ukraine quickly began to polarize. There had been ‘anti-Maidan’ rallies in the east—Kharkiv, Donetsk, Luhansk, Dnipropetrovsk—since late 2013, though these were largely orchestrated by Yanukovych and the ruling Party of Regions. After Yanukovych was toppled, the mobilizations in the east became more decentralized, with a more grassroots character, and more intense—especially with the Russian intervention in Crimea. There was a lot of opposition to the new government, and demands for more devolution of power to the regions.

Among the Russian-speaking areas of Ukraine, Crimea seems to have stood somewhat apart even before the annexation.

It was always a problematic province of Ukraine. From 1992 to 1995, the peninsula had its own separate constitution, proclaiming that Crimea is an autonomous republic which delegates some powers to Ukraine; Kuchma abolished it and instituted direct rule for a few months, until a new constitution was agreed. The second option in the March 2014 referendum, other than joining the Russian Federation, was to stay in Ukraine but revert to the 1992 Crimean Constitution.

The fact that Khrushchev transferred the peninsula from Russia to Ukraine relatively recently must also have counted, especially in Russian public opinion?

That’s one of the ideological explanations offered, yes. But other parts of Ukraine were also added to it not that long before: parts of the northwest belonged to Poland until 1939; parts of the southwest were Romanian until 1940; Transcarpathia was Czechoslovakian territory before the Second World War, occupied by Hungary during the war and then given to Ukraine in 1945. And if one is going into these historical discussions, then of course the Crimean Tatars were there much earlier, along with other peoples. Now they are something like 12 per cent of the population there. They very much opposed the Russian annexation, and boycotted the March referendum en masse.

What do you think Russia’s motivations were for seizing the peninsula?

Either domestic concerns, trying to forestall a revolution in Russia, or a desire to lay down a warning to Kiev and the West. Economically, it doesn’t make much sense for Russia to absorb Crimea. It’s one of the poorest parts of Ukraine, dependent on Kiev for subsidies; it would actually be beneficial for Ukraine not to have to pay for it. There is some economic activity associated with the navy, around Sevastopol in particular, but much of Crimea’s industry collapsed in the 1990s, and tourism didn’t become especially profitable—it’s cheaper for Russian tourists to go to Turkey or Egypt. The whole southern coast, with its unique subtropical climate, has been carved into privately owned territories rather than developed for tourism. Agriculture is not in a good state either. It would require really serious investment to keep the Crimean economy afloat—a lot of investment for little return. The demographics are also very bad there: something like 20–25 per cent of the population is economically active, the rest are pensioners and schoolchildren. The peninsula’s infrastructure is very much connected to Ukraine—this is one of the reasons why it might have made sense for Khrushchev to transfer jurisdiction over it. Crimea gets fresh water for agriculture from Kherson province, and there is no way of getting supplies in by land without crossing through Ukraine. In short, it was obvious from the start that Crimea would be a huge burden for the Russians. The potential benefits from Black Sea shelf gas and from a possible straightening of the South Stream pipeline route via Crimea, as well as military concerns about the naval base in Sevastopol and Ukraine’s joining nato, were not, I think, the main reasons for the Crimean annexation, but rather additional bonuses. The primary reason was to boost Putin’s support with a ‘small victorious war’.

After the Crimean annexation, the focal point of tensions moved to Donetsk and Luhansk provinces, where separatist groups formed in March and began to seize local administrative buildings. What distinguishes these two regions from the other, predominantly Russian-speaking areas of eastern and southern Ukraine?

I don’t know how far back we want to go, but right up until the eighteenth century this area was dikoe pole, the ‘wild field’ of steppe dominated by nomads—latterly the Crimean Tatars. Russian and Ukrainian peasants began to colonize the steppe, and then the Imperial government became involved, inviting Germans, Serbians, some Jews to the area. But when coal was discovered, and especially when the railways were built in the second half of the nineteenth century, it became a vital industrial region. Workers from various parts of the Russian Empire came to work in the Donbass mines in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and with Stalin’s industrialization drive the workforce expanded massively. Since then, it’s been the most industrial area in Ukraine, and the most urbanized. It’s also the most populous region, home to more than 6 million people, over 13 per cent of the national total. The economy in Donetsk and Luhansk is mainly based on old Soviet enterprises: coal mines, metallurgy plants. The oligarchs more or less stole these factories from the state during the bandit privatizations of the 1990s. These are still very big industrial concerns—Akhmetov, for example, employs something like 300,000 people in his Systems Capital Management group. Many of these plants sell most of what they produce to Russia—so besides any other considerations, this is one major reason why they’d want to avoid serious conflict with Russia. They’re simply afraid for their jobs. Structurally, it’s not dissimilar to the reasons people in western Ukraine have for supporting European integration—the Association Agreement was seen as a way of making things more secure for those working illegally in the eu or with relatives there.

The connection with Russia is perhaps also one reason why pro-Russian mobilizations were stronger in these areas than in, say, Dnipropetrovsk or Odessa, where the local economy is much less closely tied to Russia. Kharkiv is an interesting case—it was the first capital of Soviet Ukraine, but there hasn’t been as much separatist agitation there. Some of this is also to do with how the interim government in Kiev handled the situation: after the ‘anti-Maidan’ movement started building barricades and seizing government buildings in the eastern cities, they dispatched interior minister Arsen Avakov to Kharkiv, National Security Secretary Parubiy to Luhansk and First Deputy pm Vitaliy Yarema to Donetsk. Only in Kharkiv did they succeed in blocking further separatist mobilizations, I suspect through more effective negotiations. It’s also true that in Dnipropetrovsk, Kolomoyskyi seemed to establish himself in power quite effectively after he was appointed as the region’s governor by Kiev. He was able to organize and pay for pro-government battalions there, and seemed to gain the local population’s trust.

Were there also cultural and ideological roots to the revolt in the east?

Another particularity of the Donbass is that ethnic identity has historically been much weaker than regional and professional identities. They have always had a mix of nationalities there, but this wasn’t considered important. They have always seen themselves as Donbass people or as miners first. In western Ukraine it’s the other way around: national identity is much more significant. It partly explains why the people in the Donbass rejected Ukrainian nationalism, which seemed completely alien to them. The Maidan’s tolerance for the far-right groups’ veneration of Bandera was also a factor mobilizing people in the east. Obviously Russian propaganda depicted the whole movement as consisting of banderovtsy, which was a huge exaggeration. But for the older population especially, victory over the Nazis was a crucial element in the construction of a kind of Soviet national identity, neither Russian nor Ukrainian, and the presence of so many red-and-black flags and portraits of Bandera at the Maidan was a powerful reason for them to reject the new government.

Language seems to have been another flashpoint. What is the status of Russian in Ukraine, both officially and unofficially?

Formally, Ukrainian has priority: it’s the only state language. But the formal situation differs from the real one, since around half the population uses Russian, and almost everyone reads and understands both. Historically, Kiev was predominantly Russian-speaking, as were most of the cities and towns, while the rural areas were more Ukrainian-speaking—though this was also in part a consequence of the Russian Empire and then of Soviet Russification policies, put in place after a short period of Ukrainianization in the 1920s. Today, Ukrainian is stronger in the state realm but Russian-language culture dominates the market arena: the majority of books, magazines, newspapers are in Russian, for example. Until recently, foreign films were dubbed predominantly into Russian, not Ukrainian. For the nationalists, the development of Ukrainian-language culture requires that Russian be pushed out. But it seems to me that other solutions are possible: why not give more state support to Ukrainian-language culture, like subsidies for books, funding for schools, artists, writers, theatres, film directors? But of course this would require some state expenditure and investment, which would make it an anti-neoliberal policy. So instead what they have done is mobilize nationalist sentiment.

In 2012, in the face of strong resistance from the nationalists, the Rada passed a law saying that if the census shows that an ethnic group accounts for 10 per cent of the population in a given area, the local government has the right to give their language the status of regional language. So this was not a challenge to Ukrainian as the state language, and it was not only about Russian—there is a Bulgarian minority, a Romanian minority, a Hungarian minority, a Tatar minority, who all have the right to a regional language. But the Party of Regions used this as a tool to mobilize a pro-Russian electorate, deflecting attention away from social and economic issues to a kind of culture war with western Ukraine. The nationalists were almost euphoric—these were their issues, they were fighting for their native language. On the first day it met after Yanukovych’s fall, the new parliament cancelled the language law. This was a really inflammatory move—people in eastern Ukraine already felt themselves as somehow second-order people on the language issue. At the end of February, in the face of anti-government mobilizations in the east, acting president Turchynov cancelled the decision to cancel the law. In a way this sets a limit on nationalist cultural policies in the future.

How would you assess the scale and importance of Russian involvement in the anti-government revolts in the east?

Russian citizens were certainly involved in the anti-Maidan protests—for example in Kharkiv in early March, it was a man from Moscow who tried to put a Russian flag on the regional administration building—but you couldn’t say they were entirely driven from the outside. To begin with, the protesters were very diverse: some demanded separation or union with Russia but many others would have been satisfied with referendums on self-determination and Ukraine’s federalization. And they were also afraid of Right Sector, of people coming to their cities and toppling the Lenin monuments, which had been happening across Ukraine. These were quite large mobilizations—in Donetsk there were tens of thousands of people on the streets in early March.

But a turning point came in early April, with the arrival of Russian volunteers, very well equipped, who organized the armed seizure of Sloviansk. Many of these are far-right Russian nationalists with very conservative views, whose interests go far beyond the Donbass—for them, Kiev is the mother of Russian cities, and they think they should annex a much larger part of Ukraine than just the east. These people really had an influence on the ideological complexion of the Donetsk People’s Republic that was declared in early April. For example the Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate was effectively declared the state church of the dpr, and the dpr constitution banned abortions, on the grounds that the defence of human rights starts at conception. The separatists’ appreciation for the Soviet past was based mainly on the imperial ideal of a great country that could compete with the American superpower; any socialist elements of that legacy were very weak. Some leftists voiced admiration for the Donetsk People’s Republic because it advocated nationalization. But their constitution gave no priority to state ownership, in fact they put private property first. The idea of nationalizing Akhmetov’s factories was raised because the oligarch’s position was quite ambiguous for a long time, and then in mid-May he came out against the separatists and tried to mobilize his workers against them—not very successfully, I would say. A crowd went to Akhmetov’s residence in late May, just as people in Kiev had gone to Yanukovych’s, demanding to be let in. But the people from the dpr tried to calm them, saying ‘we know how you feel, but not now’. It’s evident these people are not socialists, they are populist nationalists.

How far was the presence of the volunteers an initiative driven by the Putin administration?

The degree of Russian state interference is not very clear to me. Ukrainian state propaganda insists the whole movement is directed from Russia, but this is a misreading of the situation. Of course, some of the Russian volunteers could be state agents; but the majority are probably just volunteers—and there are many Russians willing to fight in Ukraine to help the Russian nationalist cause. People in the rest of Ukraine tend to see the rebellion in the east as a Russian intervention or a ‘terrorist action’, in line with the government’s announcement in mid-April that it was starting an ‘anti-terrorist operation’. But in the Donbass, according to a poll in May, 56 per cent call it a people’s revolt; for them, it is something with local roots and a local base of support, despite the participation of Russian volunteers. Either way, I don’t think their presence changes the nature of the conflict. Tens of thousands of international volunteers fought in the Spanish Civil War, and Germany and Italy sent regular troops, but this didn’t alter the fact that the conflict was an internal one, between Republicans and Francoists. If you look at the separatist fighters who have been killed by Ukrainian government forces, there are certainly a number of Russians, but a significant proportion are Ukrainians. This really is a civil war.

In the run-up to the Donetsk and Luhansk separatist referendums that were held in mid-May, it seemed as if Putin was seriously contemplating an intervention in eastern Ukraine—and the separatists were evidently hoping the Donbass would follow Crimea in joining the Russian Federation. How likely was this scenario in the first place?

I’m now not sure he was ever going to invade eastern Ukraine. The Russian army regiments massed on the border were probably put there to dissuade Kiev from any attempt to take Crimea back militarily, and above all to keep the pressure up and destabilize the situation. What Putin really needs is a loyal government in Kiev, or at least one that will not join nato or make any other anti-Russian moves. He has no interest in absorbing the Donbass into Russia—for one thing, these areas depend on state subsidies for the mining industries, and for another, there are now these armed groups and a popular mobilization with huge expectations of the Russian state. Often people used to speak of exporting revolution, but here there’s a danger of importing it. Putin’s in a tricky position domestically too: people in Russia were expecting him to intervene, so now he is under pressure from public opinion there. He may seem to be playing his hand unevenly or inconsistently, but it really reflects the complexity of his position.

At the end of May there seemed to be a turn in Donetsk, with more obviously Russian armed groups taking over the rebel government. Was this perhaps a covert attempt by Putin to get a grip on the situation?

I don’t think Putin controls these people. He does control the Russian army units near the border, quite a few of which have now been moved back. But the separatists are continuing to fight in Sloviansk, Donetsk, Krasny Liman and other areas, and it doesn’t seem as if they will be surrendering any time soon.

On 25 May, in the midst of the ‘anti-terrorist operation’, a presidential election was held in Ukraine, and won by Petro Poroshenko. Tell us first about Poroshenko himself.

He is a billionaire, the sixth richest person in Ukraine according to the Forbes list. He owns the Roshen confectionery business, hence his nickname, the ‘Chocolate King’; though he also owns other interests, like the tv station Channel 5. Politically he’s an all-purpose opportunist: he was originally in a pro-Kuchma party in the late 1990s, and was then one of the founders of the Party of Regions. After that he formed his own party, the Solidarity Party, and backed Yushchenko in 2004—in fact, he was one of the leading figures in the Orange Revolution. Later he was head of the national bank and foreign minister, and then served in the Yanukovych government as trade minister. But perhaps the major factor in his popularity today is that he supported the Maidan, and was one of the politicians who appeared most frequently on the stage in Independence Square.

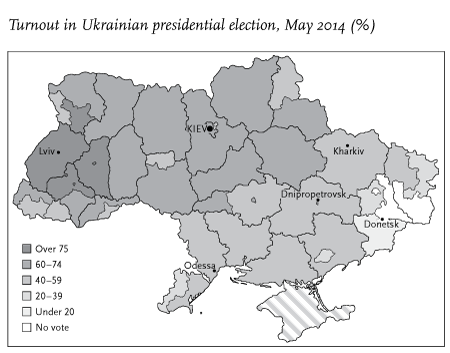

The official results of the elections seemed to indicate a landslide—Poroshenko secured a first-round victory with 55 per cent of the vote, while Tymoshenko, his nearest rival, polled less than 13 per cent. But presumably there were wide regional variations behind this picture of unanimity?

Yes, there were important geographical differences. But the first striking thing is the overall turnout—it was the lowest in a presidential election since Ukrainian independence. The official figure was 60 per cent, but this was based only on districts where the election was held. In the majority of districts in Donetsk and Luhansk, there was no voting, so these were simply excluded from the calculation. Again, these are some of the most populous parts of the country. If we add the people not voting here to the figures, the turnout would probably have been slightly over 50 per cent. Of course, there were objective reasons why many people in the east couldn’t come to the polls: there were reports of armed groups trying to stop the elections, and of electoral administrative staff being threatened. But the scale of this shouldn’t be overstated. A poll taken on election day by the Kiev International Institute of Sociology in Donetsk and Luhansk found that two-thirds of respondents were not going to vote, and of those two-thirds, around 50 per cent said this was for political reasons rather than pure intimidation: they didn’t see the election as fair, they didn’t think the Donbass was really a part of Ukraine any more, they didn’t trust the candidates. So there was quite clear evidence of a mass political boycott, hence the very low turnout even in areas where there was voting. Turnout was low in other parts of the southeast too—under 50 per cent in Kharkiv and Odessa, for example, which is 20 percentage points less than in the previous presidential election in 2010. In western Ukraine and Galicia turnout was high, and Poroshenko’s score was very high. But in most of the country, even in Kiev, fewer people voted than four years ago.

What this means is that Poroshenko is not the unifying national leader many people had hoped for—that was the idea behind holding the elections as early as possible, to have a legitimate new president who could stabilize the situation. Poroshenko is the president for the western and central parts of Ukraine, but much less so for the eastern and southern parts. There’s even some scepticism among people who voted for him. One joke which began to circulate on the very day of the elections was that the Ukrainians are the only people in the world who elect a president with an absolute majority one day and join the opposition against him the next. There’s also a certain amount of anti-oligarchic feeling—images have begun to circulate on social media blending Yanukovych’s face with Poroshenko’s, as if to say that we’ve swapped one square-faced oligarch for another; was this a victory for the Maidan after all?

The Svoboda and Right Sector presidential candidates had minimal scores of around 1 per cent each, while another far-right candidate, Oleh Lyashko, came third with 8 per cent. How do you explain this poor performance, and what is its significance?

You can’t extrapolate from presidential election results to levels of support for the parties, especially when so many people voted for Poroshenko just to get the elections over with in the first round. Tyahnybok may have scored 1 per cent, but Svoboda’s poll rating has been rising—they had 5 per cent in March, and in May they had 7 per cent. Lyashko took some of the electorate of Tyahnybok and Yarosh, it’s true; it’s not so clear that all of Lyashko’s support constitutes a far-right vote, though he was cooperating with clear neo-Nazis from the Social-National Assembly, who have a racial ideology and talk about race hierarchy and so on. So it would just be wrong to argue on the basis of the presidential results that the Ukrainian far right are not significant.

How openly do people support the far right in Ukraine? In the UK, for example, far-right voters tend to do so without admitting it in public, whereas in France the Front National’s social base is much more readily identifiable.

I think in Ukraine the whole political mainstream is far to the right of either France or Britain, and certain questions which are problematic for liberal centrists or even mild conservatives there—nationalism, race, immigration—are just not so contested here. The fact that some European countries have had far-right parties in government is seen as legitimizing the far right here—though of course it had consequences that Ukrainians themselves have suffered from, in terms of restrictions on immigration to the eu and so on. In fact, my argument would be that the rightward drift of the Ukrainian political mainstream is actually much more dangerous than the people supporting far-right parties, whatever their precise number. One very disturbing development has been the spread of dehumanizing rhetoric against the movement in eastern Ukraine. People there adopted as their symbol the black-and-orange St George’s ribbon, commemorating victory over the Nazis in what the Soviets called the Great Patriotic War. The far right then started to call eastern Ukrainians ‘Colorado beetles’, after the black and orange stripes, and now the metaphor has moved firmly into the mainstream. After the Odessa massacre on 2 May, when thirty people were burned to death in the Trade Union building, some Ukrainian nationalists were exultant. This kind of political hate speech is extremely dangerous, and it’s the first thing that must be fought.

What is Poroshenko likely to do with his mandate?

He might call for early elections, to get a solid parliamentary base. Polls are currently showing that his Solidarity Party would get around 20 per cent of the vote, which would make it one of the biggest factions. So even without changing the constitution, he might be able to amass more power than he has at present. In foreign policy terms, he’s said he will pursue a pro-European line, though of course the chances of actual eu membership are very low. What he will do about nato membership is a real question—even after the Russian intervention, this doesn’t have majority support in Ukraine. It’s certainly gone up, from maybe 20 per cent to 40, but popular opinion isn’t in favour, even in the face of a clear foreign threat. Naturally the elite is much more in favour.

What have been the effects of the ‘anti-terrorist operation’, both on domestic opinion and on the ground in the east?

At the moment, I don’t believe the reports in either the Ukrainian or the Russian media—there are so many fakes circulating, and descriptions of events are completely polarized. Ukrainian officials, military spokesmen and news media downplay the casualties on their own side, exaggerate those on the other side. It’s an information war. In terms of the combat itself, what usually happens is that the army goes to defend the perimeter of a given area, but a lot of the fighting is done by special operations units and volunteer battalions that are formally subordinated to the Ministry of the Interior. It says something that they don’t want to send conscripts to the war zones—they’re worried that the army is not going to fight for them. One of the volunteer brigades is Kolomoyskyi’s Dnipro battalion, and others are effectively oligarchs’ private armies. There’s also the Azov battalion, which includes a lot of fighters from the far right—there were pictures of them lining up under their yellow flag with the Wolfsangel symbol. Apparently they talk about going to fight on the Eastern Front, like the Germans did during the Second World War. It’s a real propaganda gift to the Russians. And it will only help to consolidate support for the Donetsk separatists.

At present the ‘ato’ is stagnating. The government in Kiev has announced the final stages of the operation half a dozen times, but it’s still going on. They will not be able to achieve military success without inflicting severe casualties on the civilian population. It’s a basic choice: either you have serious bloodshed, with millions of refugees and many cities destroyed—and that’s even if no other parties, like Russia and nato, get involved—or you negotiate. Kiev says it will not negotiate with terrorists, but these ‘terrorists’ are becoming something like legitimate authorities, in the absence of any other representative forces. If you want peace, you have to talk to them. A clear stance in favour of a negotiated solution, and against this civil war, is the most principled position available now.