The Reforging of Russian Society

The winter of 2011–12 produced a paradoxical combination of the inevitable and the unexpected in Russia.footnote1 The return of Vladimir Putin to the presidency was never in doubt; his crushing margin of victory in the March 2012 elections—officially, he scored 64 per cent, almost 50 percentage points more than the second-placed Communist Party candidate, Gennadii Zyuganov—gained him a third term in the Kremlin without the need for a further round of voting. However, the months prior to this democratic coronation brought a series of demonstrations of a scale not seen in these lands since the last days of perestroika. Tens of thousands of people took to the streets in dozens of cities, from Vladivostok to Kaliningrad—the largest gathering, on 24 December, drawing as many as 100,000 people to Moscow’s Sakharov Avenue—to protest first against the fraudulent results of the December 2011 parliamentary elections, and then against the impending reinstallation of Putin as president. On the one hand, then, seeming confirmation of the ruling elite’s unhindered control over the political system; on the other, signs of a growing rejection of that system by a substantial part of the population.

The recent wave of protests has been seen, both in Russia and in the West, as evidence of a new awakening of Russian ‘civil society’, roused from its long post-Soviet slumber by the corruption of Putin and his associates, and their brazen contempt for the popular will. The mobilizations displayed a striking ideological breadth, running the gamut from Orthodox chauvinists to neoliberals, socialists to environmental activists, anti-corruption campaigners to anarchists; attendance also spanned the generations, from pensioners to teenagers. But, as the Western press noted approvingly, the most vocal and visible component of the oppositional marches was ‘a sophisticated urban middle class’, with consumption habits and expectations not unlike those of their Western counterparts. During the years of oil-fuelled economic growth after 2000, this layer had apparently ‘grown in size and become sufficiently affluent to assert its yearning for more accountability and less corruption’. Despite its failure to prevent Putin from garnering a majority of the vote, the arrival of this seemingly new actor on Russia’s political stage marked the start of a period of uncertainty; indeed, in some quarters its assertiveness was taken to portend the ‘beginning of the end of the Putin era’.footnote2

Such auguries rely, of course, on a Whig history refurbished for neoliberal times, in which the advance of Western consumption patterns and rising gdp per capita are the measures of progress towards the liberal-democratic norm; if needed, further proof can be found in increases in car-ownership, internet usage, foreign travel, or perhaps the quantity of ikea stores in a given country.footnote3 Crass metrics of this kind have become a staple of the mainstream Western press, especially when discussing states outside the advanced capitalist core. With regard to Russia, as elsewhere, they reveal a generalized absence of knowledge about the society in question: how is it actually structured in class terms, what is the balance of forces between its components, how are class interests articulated and advanced in both the material and ideological realms? The social historian Moshe Lewin famously described the ussr of the 1920s and 30s as ‘the quicksand society’; given the depth of ignorance about what lies beneath the country’s unchanging political surface, contemporary Russia might be described as ‘the iceberg society’.

Indeed, the social landscape of post-Soviet Russia is in many ways more opaque to outsiders than was that of the ussr. In the West, this is partly due to a general shift in research patterns after the Cold War, which had generated an enormous need for knowledge about the opposing system that, after 1991, seemed surplus to requirements. Wider changes in the discipline of sociology itself also played a role—away from synthetic overviews of a society, towards questions of ethnic, religious or subcultural identity, for example, or in favour of closer, anthropological investigations of everyday experience. A third factor applies across much of the world: with the weakening of previous forms of class identification has come a diminishing sense that society itself can be grasped by the categories of class analysis. Moreover, the convulsive character of events in Russia itself after 1991 made it difficult for analysts fully to comprehend the effects of the upheaval on society as a whole.

What follows is a preliminary attempt to map the changing shape of Russian society in the last two decades, the better to understand its present condition, and its likely future trajectories. One of the fundamental enigmas this essay will seek to explain is why a society that has suffered so dramatic a series of reversals has nonetheless remained relatively stable. It will be argued that, although the fall of the ussr brought profound dislocations, many aspects of the country’s previous social structures are still in place, resulting in a form of ‘uneven development’ in which two social orders co-exist. Moreover, contrary to the conventional wisdom of liberal ‘transitology’, which blames Soviet legacies for the deformities of Russian capitalism today, it is precisely the persistence of the old that has underwritten the stability of the new. In order to obtain a clearer picture of the ways in which Russia has been remade since 1991, however, we will need to begin by sketching out the main lines of its development in the Soviet era.

I. SOVIET TRANSFORMATIONS

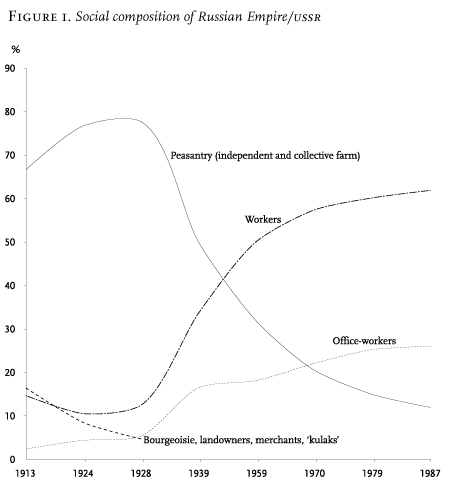

Three interrelated processes dominated the twentieth century in what became the Soviet Union: urbanization, the shift from an agrarian to an industrial base, and the system-wide installation of non-capitalist socio-economic relations. These processes unfolded very rapidly, bringing the creation of new social groups, the destruction of old ones and the expansion or metamorphosis of existing categories. Looking over a 70-year span—see Figure 1, below—we can see in broad outline what the main social outcomes in the ussr were, according to the official view (on which more shortly). Firstly, and most strikingly, there is the long, steady dwindling of the peasantry—for centuries the unmoving foundation of the Tsarist social order. In the Soviet period the peasant world was dismantled not only by urbanization and industrialization, but also by the heavy hand of repression, with the collectivization programme of 1929–32. Despite the return of some private plots thereafter, what was left of the peasantry had by mid-century been transformed into a rural proletariat. To be sure, alongside these pressures came a system of positive incentives: education, more rights for women, improved housing, sanitation, health care, and so on. But the main impact of the Soviet order on the peasantry was to destroy, for good and for ill, the traditions and life-world of this rural class—an outcome at stark variance with, for example, the fate of China’s peasant masses.footnote4

Second, there is the obviously more rapid disappearance of the propertied class after 1917. The aristocracy and landed elite was erased from the social landscape by the Revolution and Civil War; thereafter, apart from an outburst of entrepreneurialism under the New Economic Policy in the 1920s, there was nothing one could designate a bourgeoisie or even a mercantile class. Third, the rise of the category of ‘workers’. Although the October Revolution had been carried out in the name of the proletariat, industrial workers formed a relatively small proportion of the population in 1917, and shrank still further during the devastating Civil War that followed. The launching of forced-pace industrialization in 1928 brought a dramatic shift, however: between 1928 and 1937, industrial workers more than doubled in number, from 3.8 to 10.1 million; thereafter, their numbers continued to rise to the point where they dominated the ussr demographically.footnote5 This was not merely a process of quantitative growth—it was a qualitative transformation too: the Party actively sponsored the ‘making’ of an industrial working class, in the way it organized and incorporated labour, in everyday life and culture, in the realm of language and iconography.footnote6 Finally, we can also see the emergence of a layer of white-collar workers—‘sluzhashchie’ is the official term, essentially designating administrative personnel. This category also expanded rapidly after the advent of the fully planned economy, and eventually formed more than a quarter of the population.

On top of breakneck industrialization and the collectivization of agriculture, this population would face the full force of the Wehrmacht. War, famine and, to a lesser extent, political repression brought catastrophic population losses, with long-term demographic consequences. Between 25 and 30 million Soviet citizens died in World War Two, including 40 per cent of men aged 20–49, and 15 per cent of women of the same age group. The drop in the birth-rate that ensued would have its ‘demographic echo’ in the late 60s, as the missing children of the war years were not able to make their reproductive contribution as adults.footnote7 The echo would appear again in the 90s, this time reinforced by the hardships of the post-Soviet period, which would also see sharp falls in life expectancy. The mid-century scything was probably broadly proportional across classes, though falling disproportionately on the west of the country; but it should be taken into account as a concomitant social factor in the discussion that follows.

Social differentiations

The Party line was that, with the triumph of the Revolution and the construction of socialism, class antagonisms as such had disappeared. In the well-known phrase Stalin used in 1936, Soviet society consisted of ‘two friendly classes and a layer’—workers, peasants and the intelligentsia respectively. Yet these did not constitute cohesive groups to which such labels could be applied. Within the broad commonalities in their relation to the means of production, Soviet citizens were differentiated according to a number of criteria: income, skill-level, education, sex, ethnicity, economic sector, access to political power, position within the informal ‘economy of favours’ known as blat. The existence of these gradations, and the insufficiency of the official ‘2 + 1’ formula to describe them, encouraged Soviet sociologists to turn increasingly to stratification-based approaches as of the 1960s.footnote8 This methodological preference strongly inflected the empirical data that were gathered in the late Soviet era, and is still visible today. It may therefore be of heuristic value to adopt the classificatory schemas used in the ussr and post-Soviet Russia, to track the development of these categories over time; with the proviso that this does not constitute an endorsement of their theoretical foundations.

Social differentiation unfolded very unevenly not only between but also within distinct segments of the population. A further factor in the subdivision of the population, beyond those enumerated above, was the cellular organization of Soviet society. For as Simon Clarke has observed, its ‘primary unit’ was the enterprise, which not only incorporated workers into the labour force, but was also the source of housing, welfare, healthcare, education and other benefits.footnote9 There were gradations within each enterprise, of course; there was also a great deal of variation between enterprises, both according to economic sector and by region. The combined effects of cellular organization and other social distinctions generated patterns that are difficult to summarize; here we will examine the general picture, taking the main forms of differentiation noted above in turn—but bearing in mind at all times the range of particularities lurking beneath it.

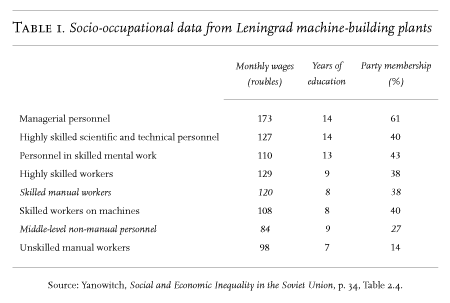

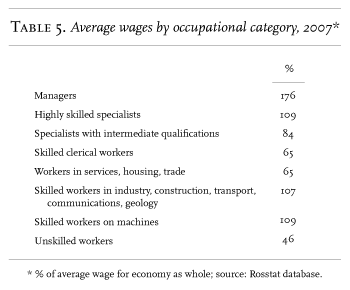

After the Revolution, there was an initial period of social levelling: large estates were redistributed to the peasantry, housing in cities was reallocated according to class criteria, and so on. Incomes also evened out, as the technical and administrative personnel of the old regime saw their salaries reduced and underwent a process of déclassement. But these tendencies were subsequently reversed: the nep period brought a certain degree of inequality in income and wealth, and in the 1930s wage differentiation became a matter of policy, amid official campaigns against uravnilovka—‘equality-mongering’—which was seen as a leftist deviation. Workers were now provided with material incentives to boost productivity; by the mid-1950s, the average wages of the top decile of earners were just over 8 times higher than those of the bottom decile. Under Khrushchev, wage differentials narrowed again—the ratio of top to bottom deciles by wages dropped to 5.1 by 1968, and to 4.1 by 1975.footnote10 Wages varied significantly by economic sector. Thus coal miners earned twice as much as textile workers, and significantly more than engineering-technical personnel in a wide range of sectors.footnote11 Table 1, below, showing data from machine-building plants in Leningrad in 1965, indicates a typical spread of wages earned by different socio-occupational groups.

These data also allow us to see several other important features of the Soviet social structure, notably with regard to skill-level and education. Though many scholars felt that the Soviet bloc and the West were converging within a paradigm common to all industrial societies,footnote12 there were important distinctions. Firstly, in the ordering of the occupational strata: in the ussr, the status and incomes of skilled manual workers were in many cases higher than those of unskilled non-manual ones. Thus, as can be seen in Table 1, the positions of skilled manual workers and unskilled non-manual workers (both italicized) are reversed relative to their usual positions in the West. This will have important consequences further down the line.

A second feature is the weights of the different strata within the population—and in particular of unskilled workers. Historically, these had been dominant within the workforce, accounting for as much as 65 per cent of it in 1940; Moshe Lewin used the neologism rabsila (from rabochaia sila, ‘work force’) to designate these workers, many of them recently emerged from the ranks of the peasantry. They were ‘cheap and formless’ labour, ‘a crude labour force, rather than a working class’, which could be thrown en masse from one gargantuan industrial or infrastructural project to another; the lurching, collective demiurge of the Great Breakthrough.footnote13 The processes of urbanization and expanding education reduced the unskilled component in the post-war era, but even in the 1980s, Lewin estimated the unskilled labour force at 35 per cent of the population. The bulk of this late-Soviet rabsila came from the southern tier of the Union, from Central Asia and the Caucasus, where rural worlds had fractured yet not given way to industrial urbanism; Georgi Derluguian, borrowing terminology Pierre Bourdieu developed with regard to Algeria, has designated this ‘inchoate, residual’ group a ‘subproletariat’.footnote14 In the late Soviet era this population took part in massive, regular labour migrations known as the shabashka; after the fall of the ussr, many of these people suddenly ceased being internal migrants and became ‘foreigners’, to whom the term Gastarbeiter began to be applied.

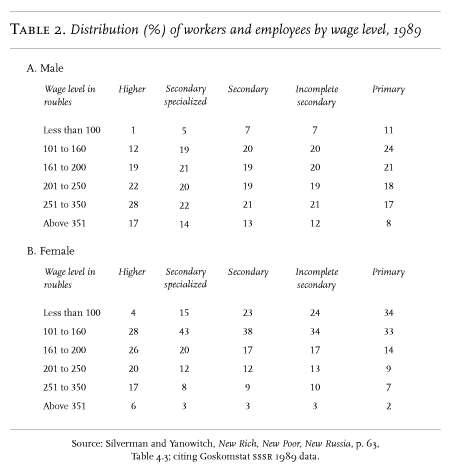

Looking at the second column of figures in Table 1, we can see that highly skilled workers earned more than technical specialists, despite having less education. This is a third distinctive feature of the ussr: neither skill-level nor education had the determining effect on either income or position in the status hierarchy. This emerges clearly from the data in the upper panel of Table 2, below: the proportions of Soviet men in the various wage brackets, while certainly not equal, were nonetheless not dramatically uneven across most of the different educational levels. However, as the data in the lower panel show, the same was emphatically not true of women. Soviet women were clearly clustered towards the lower end of the wage hierarchy, at all levels of education with the partial exception of those with higher qualifications. The degree of women’s participation in the labour force was a very striking characteristic of Soviet society: at 84 per cent in 1989, one of the highest in the world; much higher than, say, the uk (43 per cent) or West Germany (35 per cent); and this is not including another 7 per cent in full-time education. By the 1970s, they outnumbered men in the workforce, 52 per cent to 48.footnote15 This is all the more remarkable when one considers that Soviet women still had to bear the main burden of housework and child-rearing. Women also tended to be clustered in particular occupations or sectors. As of the 1950s, they formed the majority of workers in a number of white-collar posts; according to the 1970 census, women constituted 75 per cent of teachers, doctors and dentists, 95 per cent of librarians, 63 per cent of staff in governmental and economic administration. What Gail Lapidus described as a ‘polarization’ between ‘male-dominated and female-dominated sectors’ formed the basis on which the new unevennesses of the gender landscape in post-Soviet Russia were built.footnote16

New class or category?

Returning to Table 1 once more, we can see one variable that does correlate with place in the status and income hierarchy: Party membership. The Party–state elite notably did not feature in Stalin’s ‘two classes plus a layer’ formula; yet for some critics of the Soviet system the nomenklatura constituted a class in itself—as in the title of Milovan Djilas’s 1957 book The New Class. But what kind of class could this be? According to Olga Kryshtanovskaia, the leading contemporary Russian sociologist of the elite, the highest echelons in the ussr numbered between 800 and 1,800 people, but if one includes the various Party committees and subcommittees at republic, region and local levels, the full size of the nomenklatura was 400,000 people.footnote17 This nomenklatura was of course only a fraction of the much larger Party membership, which in the mid-60s stood at around 12 million, and by the mid-80s reached almost 20 million. These members were in turn drawn from across society: in 1968, for example, 39 per cent of cpsu members were manual workers, 45 per cent non-manual workers and 16 per cent collective-farm peasants; by 1981, the share of manual workers had risen to 44 per cent, that of non-manual workers slid to 44 and collective-farm peasants dropped to 13 per cent.footnote18 Thus while the Party membership did not accurately reflect Soviet society as a whole—non-manual workers were over- and the peasantry under-represented—it was not a closed, elite organization either. Pace Djilas, the nomenklatura was correspondingly not a separate ruling caste that floated above the cpsu membership, since its cadres were recruited from the Party’s mass base.

Rather than seeing the Party as a separate ‘new class’, then, it may make more sense to deploy other concepts. Nicos Poulantzas put forward the term ‘social category’ to describe ‘an ensemble of agents’, drawn from various classes, ‘whose principal role is its functioning in the state apparatuses and in ideology’; he gives the administrative bureaucracy and the intelligentsia as examples.footnote19 Such categories ‘do not in themselves constitute classes’. Yet they can ‘present a unity of their own’, and ‘in their political functioning, they can present a relative autonomy vis-à-vis the classes to which their members belong.’ In the case of the cpsu, the Party as social category was not only able to gain a degree of autonomy from its base; its monopoly on political representation enabled it to prevent the articulation of interests separate from its own. With its combination of social heterogeneity and domination of the political sphere, the Party was in a sense a powerful antibody against the formulation of distinct class interests in Soviet society.

But while the cpsu as a ‘category’ drew its members from various classes, it did not do so equally. If we examine the degree of Party ‘saturation’ at various levels of the organizational ladder, for example, we see that in the late 1960s, 99 per cent of factory directors were Party members, as were 51 per cent of sub-directors, 38 per cent of foremen and junior supervisors, compared to only 18 per cent of workers.footnote20 The hierarchies in the realm of production were thus interwoven with—both reinforcing and reinforced by—differentiations rooted in the political sphere. As we have seen, in the ussr hierarchies of income, skill, education and so on were relatively flat compared with Western states. In the absence of a possessing class that would be distinguished by its ownership of the means of production, proximity to the Party–state apparatus became a key criterion of differentiation. Varying degrees of political pull sharply marked out Soviet citizens from one another: membership in or connections with the Party shaped the life-chances of parents and children, giving some of them access to scarce goods and opportunities, as well as affording them an extensive network of formal and informal privileges. Borrowing from Bourdieu, we might term this ‘political capital’, possessed in different volumes by distinct groups of social actors.footnote21 The relatively higher prestige of manual workers in Soviet society was, in a sense, a form of congealed political capital, a legacy of the ideological preferences of the October Revolution. The political capital of the nomenklatura was to prove crucial in the post-Soviet period, as the foundation for a powerful new wave of social differentiation.

II. CONSEQUENCES

Tatiana Tolstaya’s 2000 novel The Slynx unfolds in a post-apocalyptic Russia that has somehow returned to a medieval condition in the aftermath of an unspecified disaster known simply as The Blast. The mysterious catastrophe has not only wiped away nearly all traces of the preceding civilization, it has inflicted strange mutations on everyone, known in the book as Consequences. Not all Consequences are the same: one person has gills, another has a tail, a third has the ability to breathe fire; each is alone in their deformity or new capability. This is a powerful metaphor for the post-Soviet experience, capturing the world-historical bewilderment and dislocation that followed the collapse of the ussr—the proliferation of unfamiliar figures in the social landscape, from millionaires to vagrants, as well as the atomization of collective identities into disparate, individual destinies. But in one crucial sense it is misleading: the new, post-Soviet Russia was not built on a tabula rasa, it emerged from within the carapace of the ussr—inheriting many of the preceding order’s peculiarities, transforming them or exaggerating them into new shapes. This prolonged reforging of Russian society could be divided into three phases, the first running from 1991 to the rouble crisis of 1998; the second from 1998 to 2009; and the third setting in when the effects of the global economic and financial crisis began to be felt in Russia.

Birth of an elite

Within the tumult of the 1990s, an unambiguous process of class formation was taking place, from the top down. The principal mechanism that drove it was the programme of privatization carried out by the Yeltsin government, under tutelage from imf officials and us advisors, which effected a massive transfer of state assets into private hands. As of 1987, a ‘latent’ privatization had been taking place in the ussr, centred in the realm of finance and led by the Party’s youth wing, the Komsomol.footnote22 But the private fortunes that began to be amassed during perestroika were still eminently dependent on political connections—a provisional wealth accorded by the state, rather than a form of patrimony that could be guaranteed beyond any individual’s life-span. The transition to capitalism offered the Soviet elite the opportunity to convert power into property—and so to become a bona fide possessing class.

The emergence and consolidation of this elite could not have taken place without the decisive intervention of the state. Yeltsin’s project of capitalist transformation was initially based on legislation passed by the elected parliament; but when the legislature offered resistance, Yeltsin brought tanks onto the streets to resolve the deadlock, bombing the Supreme Soviet into submission in October 1993. Two months later, he rammed through a hyper-presidentialist constitution, approved by a referendum marked by widespread electoral fraud; United Russia’s recent efforts pale by comparison with this rigging of the entire juridical basis for the Russian state. Constitutional and democratic norms were evidently secondary considerations for the Yeltsin administration; the primary one was the creation of a stratum of private property-owners.

The initial stage in this project was the mass privatization drive of December 1992 to June 1994, in which some 16,500 enterprises, employing two-thirds of the industrial workforce, were sold off through ‘voucher auctions’. The majority of these nominally transferred half the shares to the workers, but the dominant position of industrial directors meant that in practice, the auctions ‘allowed factory managers to privatize their enterprises without losing control over them’.footnote23 In agriculture, supply and procurement were privatized, but farm directors obstructed Yeltsin’s plans for full privatization of land—announced three weeks after the shelling of parliament—since these would generally involve breaking up large farms into smaller ones. Though achieved by opposite means, the outcome in agriculture was similar to that in industry: managerial control was strengthened, and turned into de facto or even de jure ownership of the land. Privatization of the retail sector also proceeded apace as of 1992, creating tens of thousands of small business owners; but it moved more slowly in housing, since it was not the federal centre, but regional governments or enterprises that held title to buildings. Here the pace depended largely on the fate of local industry and the configuration of local politics, leaving the housing market as a whole fragmented and poorly developed for many years.

Despite its seemingly broad scale, the privatization wave of 1992–94 ‘specifically left most of the valuable property in the country to be privatized through channels that could be closed to most Russians’.footnote24 Notably, the enterprises formerly run by the Soviet fuel and energy ministries—including such behemoths as Gazprom—were sold off or turned into ‘joint-stock companies’ by presidential decree as of mid-1992. These opaque transactions made the fortunes of a handful of oligarchs in the energy sector; a pool of magnates effectively created by state fiat, away from democratic scrutiny. Something similar was taking place, more unevenly and on a smaller scale, at the regional level, as local governors—appointed by Yeltsin until elections were introduced in 1996—disposed of state assets under their purview. The picture across the 80-plus federal components of Russia was highly complex, embracing a range of scenarios from enthusiastic free-market reform to the installation of personalized patrimonialism. But here too, there was a top-down process of elite creation: ‘the governor in effect “formed the elite” by overseeing the privatization process, serving as a midwife to the creation of financial-industrial groups, selecting new owners and managers’.footnote25

Further state assets were put on the block in 1994–97; but perhaps the dominant features of this second stage were an intensifying struggle over already privatized assets, and the creation of private enterprises by state functionaries in the realms for which they were responsible—pod sebia, ‘under oneself’. At the regional level, second-tier industrial groups with close ties to local governments—often of a nepotistic kind—began to consolidate themselves into conglomerates. On the national plane, the oligarchs who had emerged in the preceding years extended their reach—notably through the infamous ‘loans-for-shares’ deals of November–December 1995, in which the Yeltsin government held rigged auctions for stakes in several oil and metals companies: yukos, Sibneft, lukoil, Surgutneftegaz, Norilsk Nickel, Mechel. These were acquired for a fraction of their value by figures such as Vladimir Potanin, Boris Berezovsky, Mikhail Khodorkovsky and Mikhail Prokhorov; the first two entered the cabinet after Yeltsin won re-election in 1996, suggesting the government too had been partly privatized.

By the mid-1990s, then, Russia visibly possessed an elite marked by fabulous extremes of wealth, which had acquired not only prized sections of the Soviet industrial base, but also assets in banking, transport, construction, as well as developing media empires that would forward their interests in the realm of ideology. The richest of the Yeltsin-era oligarchs were relatively heterogeneous in their social origins—the sons of engineers, academics and teachers as well as of Party functionaries.footnote26 Mostly not Muscovites, many of them laid the bases for their fortunes through cooperatives formed in the late 80s, while others made use of Komsomol connections. Looking beyond the oligarchs to the new class of post-Soviet owners as a whole, however, the continuities with the Soviet-era political and managerial elite were far stronger—as with the post-Communist political class, the bulk of which was drawn from the ranks of the cpsu. Kryshtanovskaia distinguishes between a political elite and what she terms a biznes-elite; in 2001, 77 per cent of the former, and 41 per cent of the latter, came from the nomenklatura.footnote27 It is worth noting that these two groups combined are considerably smaller than the old nomenklatura. Kryshtanovskaia numbers the upper echelons of Party and state at the close of the Soviet era at 2,500 people, whereas the 1993 Yeltsin cohort numbered only 778 people; that is, the ranks of the political and economic elite, already far from inclusive, narrowed considerably after 1991, while their material advantages over the rest of the population rose vertiginously.footnote28

The Centrifuge

Alongside the creation of a new elite, a process of mass pauperization unfolded—as if the country’s population were being separated out by centrifuge. The context in which Yeltsin’s privatization programme was conducted was one of economic catastrophe and social crisis for the vast majority of the population: gdp contracted by 34 per cent from 1991 to 1995—a greater decline than in the us during the Great Depression—while over the same period, average real wages dropped by more than half and employment was significantly reduced, in some sectors by as much as 20 per cent. The crime and murder rates doubled in the early 90s, and public health deteriorated with incredible speed: male life expectancy, for example, shortened by five years between 1991 and 1994.footnote29 The poverty rate, already rising as the ussr neared collapse, soared after the freeing of prices in January 1992: an ilo study from that year claimed that as much as 85 per cent of Russia’s population now found themselves below the poverty line. The answer to this problem was not, of course, to change the policies responsible, but to alter the measure of poverty. Once a new definition was devised, the poverty rate was immediately reduced to around 36 per cent.footnote30

The depth of the social crisis was amplified by the dissolution of the Soviet system of provision. Some benefits—housing, childcare—continued to be provided through the workplace, though this depended greatly on the fate of the enterprise itself, and on the inclinations of the new managers and owners. But the central government effectively abdicated responsibility for the welfare, education and health-care systems, increasingly delegating their provision to the local level; by the mid-90s, ‘85 per cent of social spending came from regional and local budgets’.footnote31 The result was to consolidate and deepen existing disparities between regions, adding a marked geographical component to the process of socio-economic separation of the population. Moscow and St Petersburg, along with regions possessing resource endowments or access to export markets, could afford to maintain a semblance of social provision that was beyond the reach of depressed industrial regions or the poor, non-ethnic Russian fringes of the country—for example the North Caucasus, or the republics of Tuva and Buryatia on Siberia’s southern edge.

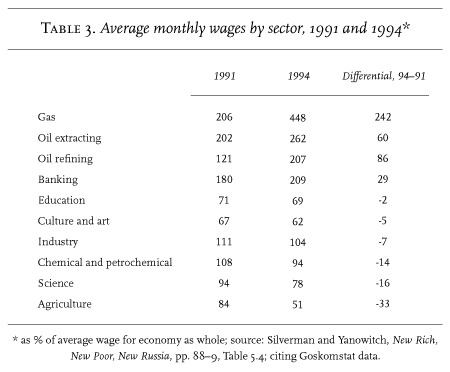

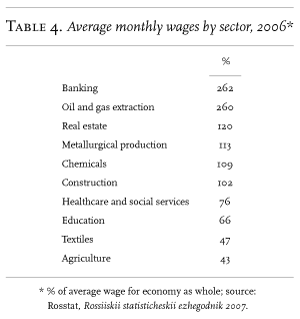

It is against this backdrop of social crisis and accelerating spatial differentiation that huge inequalities in income rapidly emerged. According to World Bank data, in 1988 Russia had a Gini coefficient of 0.24, which would place it in the company of, say, Sweden; by 1993, the figure stood at 0.48, putting it on a par with Peru or the Philippines. These numbers are for officially declared income, and so surely understate the reality by some distance. The existing wage gap between socio-occupational groups widened: by 1994, top managers on average earned five times as much as skilled urban workers, and ten times as much as unskilled rural ones. This socio-occupational dispersion, however, leaves aside the dramatic differentiation taking place ‘not between but within occupations’, according to economic sector.footnote32 Relative to the average wage in the economy as a whole, workers in the oil and gas sectors made significant gains between 1991 and 1994, whereas those in agriculture, education, culture and above all science lost out (see Table 3).

The process of ‘transition’ also amplified existing gender imbalances. This was in part because those sectors and occupational strata dominated by women were among the worst affected by cuts in employment, drops in real wages or serial non-payment of wages. Moreover, while women had been under-represented in the upper echelons of the Party and industrial management, the elimination of Soviet-era quotas sharply reduced their presence—from 30 per cent to 8 per cent, for example, in the case of the legislative apparatus.footnote33 The new world of biznes was even more strongly male than the Soviet nomenklatura. But perhaps most striking was the mass withdrawal of Russian women from the labour force: two million women left employment between 1991 and 1995, accounting for an estimated 50 per cent of the labour ‘shed’ in this short period. Though some opted to retire, on the whole the choice was not freely made, but was rather ‘a reflection of declining economic opportunities and available child-care services’.footnote34 Moreover many women, already bearing the main burden in the home, were now pushed into becoming the main breadwinners by engaging in petty trade.

Indeed, petty traders were among the most visible of the new social categories that emerged in the 1990s. There was a sudden proliferation of street-vendors, from roadside kiosks to pensioners standing in sub-zero temperatures to sell cigarettes or their veteran’s medals; and there were shuttle-traders or chelnoki, who would travel long distances to buy goods and then resell them locally. Petty trade was a crucial source of income for many people—not only due to widespread unemployment, but also because so many went unpaid in their ‘main’ job, as the Yeltsin government implemented an imf-decreed tight monetary policy that starved the economy of cash. By the autumn of 1996, according to one measurement, some 60 per cent of employees were owed back wages; with payment arrears sometimes reaching six months, many people were obliged to hold two or more ‘jobs’.footnote35 Yet most ‘second’ jobs did not provide sufficient income or security to justify abandoning one’s primary employment; thus many of the new categories overlapped with existing ones.

However, one expanding category that was clearly demarcated from the old ones was that of the ‘dispossessed’, which included the unemployed, ethnic Russian refugees from other ex-Soviet republics, demobbed soldiers, the disabled, vagrants, the homeless, among others.footnote36 Pensioners were perhaps the most visible, and piteous, of the new poor in Russia: veterans of war and industry reduced to penury by the combination of spiralling prices and tight state spending produced by ‘shock therapy’. By the end of 1992, 40 per cent of pensioners were receiving monthly payments less than half the declared subsistence level.footnote37 In addition to the differentiations noted above, a chronological fractioning of the population was taking place, as the elderly generations were written off by the country’s new rulers. It is hard not to feel the chill emanating from the words of Boris Nemtsov, then first deputy prime minister, who stated in the spring of 1997 that ‘Russia must enter the twenty-first century only with young people’.footnote38

The creation of new social groups unfolded in parallel with a sweeping process of ‘unmaking’ of the Soviet world. This applied especially to the industrial workforce, who experienced a speeded-up version of the deindustrialization that has engulfed rustbelt areas across much of the globe. The Soviet variant of this process was distinguished not only by its speed, however, but by the specific character of the Soviet system, in which, as noted earlier, the enterprise was the ‘primary unit’ of society. The loss of work thus not only involved a loss of income, but also of the whole web of connections that bound one to a community and, equally or more importantly, secured one’s housing and access to social services.

The quiescence of Russian labour has long puzzled outside observers: why this relative passivity from workers who had only a short time before—notably the coal miners in 1989–91—played such a prominent and active role?footnote39 The dissolution of the material bases of their collective existence clearly played a decisive role—unemployment and atrophying industry undoing the web of the old relations of production. The world-historical disorientation occasioned by the Soviet collapse was surely another crucial factor: the disintegration of a state that represented, however nominally, the interests of the workers as against those of global capital would have been a severe blow to the self-confidence of the class as a whole.

Another, less immediately apparent part of the answer might also lie in the specific mode of labour’s integration into the Soviet system—the paternalistic, cellular structure centred around the enterprise. Amid the turbulence of market reform, workers and management alike found common cause in preserving the enterprise, and hence maintaining production. The trade unions, which generally continued to operate as under the Soviet system—focusing on the smooth running of production rather than on representing the workers per se—played a key role here, since they retained a large degree of control over access to housing, childcare and other benefits. Most workers could not possibly forego these essentials, and hence were willing to accept a reduction in hours or salary if it would preserve their place in the labour collective. Rather than laying them off, many firms instead kept workers on the books, part-time or merely nominally. The result was that unemployment levels in Russia in the 1990s, though high compared with the past, were low compared to other East European countries: 9 per cent in 1995, as against figures of 15 per cent for Poland or 17 per cent for Lithuania. Underemployment, hidden forms of unemployment and the dual work patterns noted earlier became very widespread, and protest was subsumed by the imperatives of survival.

If the end of Communism served to atomize and demoralize the Soviet working class, its impact on the intelligentsia was no less profound. The bulk of the country’s intellectual and artistic elite had been prominent supporters first of Gorbachev’s perestroika, as presaging a liberation from the dead weight of cpsu orthodoxy, then of Yeltsin’s shock therapy—including his assault on the parliament in 1993—as necessary steps on the road to ‘democracy’ and ‘civilization’.footnote40 These commitments ensured Yeltsin a degree of support at striking variance with the harsh 1990s experience of the intelligentsia as a whole, which, defined more broadly to include the vast Soviet scientific and technical apparatus, suffered a dramatic form of déclassement under the new capitalist dispensation. The strategic-military purposes underpinning many scientific institutes and programmes evaporated with the end of the Cold War, and basic funding for research in all fields dried up, in many cases disappearing altogether. Thousands of academics and technical personnel were thrown into unemployment, or else continued their work on minimal or non-existent resources, moonlighting as taxi drivers or shuttle traders to make ends meet.

The downward lurch after 1991 was in that sense especially strong for this layer, both objectively and subjectively: having helped to turn an agrarian empire into a global superpower—complete with nuclear arsenal, space programme, advances in astrophysics and cybernetics—they found themselves marking time amid its ruins. The cultural sphere is often able to function on meagre means and spring back from crisis quickly, as the dynamism of Russian art and literature of the 1920s proved. The experience of the 1990s, however, showed that scientific and technical foundations built over generations can be eroded with dramatic speed. Russia’s losses in this realm seem thus far to have proved irrecoverable, despite the economic rebound that set in at the turn of the new century.

III. STABILIZATION?

The rouble crisis of 1998 was a significant inflexion point in Russia’s post-Soviet trajectory. It by no means halted the production of inequalities. But it did shift the centre of gravity of the economy, away from the financial sector that had nourished capital flight and stoked exchange-rate pressures in the run-up to the crisis, towards the country’s resource-extraction and industrial base. Domestic production received a strong boost from the fourfold devaluation of the rouble; agriculture too began to stage something of a recovery, after a surge of imports in the 1990s had rendered much of it unprofitable. The crisis thus laid the groundwork for the economic boom that followed the sharp rise in oil prices after 2000. These auspicious conditions, in which the incomes of many ordinary Russians rose markedly, provided a lasting popular basis for Vladimir Putin’s programme of neo-authoritarian recentralization. After the turmoil of the 1990s, Russia seemed to many to have entered a phase of stability. It is perhaps indicative that in 2003, an annual sociological conference held since 1994 with the title ‘Where Is Russia Going?’ changed its name to ‘Where Has Russia Arrived?’

There is a large degree of truth to this view: in 2004, Russia’s gdp finally surpassed its 1991 level, and by this time the country had clearly regained some of the ground lost on several other indicators—health, crime, life expectancy, and so on.footnote41 The pace with which inequality was advancing also seemed to drop: whereas the Gini coefficient was 0.48 in 1996, by 1999 it had dropped to 0.37, and to 0.36 by 2002. However, the coefficient began to climb again thereafter, reaching 0.44 in 2007. Again, it should be stressed that these figures cover only declared income, not wealth or capital gains, and thus considerably understate the actual inequalities that obtain in Russia. The share of income held by the bottom decile remained miserly: it rose from a mere 1.5 per cent in 1993 to 2.4 per cent in 1999, peaking at 2.7 in 2002 before dropping to 2.2 again in 2007. There was a noticeable decline in the official poverty rate, from 29 per cent in 2000 to 15 in 2006; but even then, this meant 21 million Russians were officially living in poverty, and the real number was probably significantly higher than this.footnote42

The stabilization observed after 1998, then, did not bring any deeper rebalancing of Russian society. Rather, it might best be described as a consolidation—a solidification of the formation that had emerged in the tumultuous preceding phase, preserving and in many cases deepening the disparities that were already present. This was especially apparent with regard to the country’s uneven economic geography, as rising prices for natural resources fed a boom in some areas while others continued to stagnate. The geographer Vladimir Kaganskii has referred to the role played by the military-industrial complex in linking the spaces of the Soviet Union; post-Soviet Russia, he claims, is bound together by the pipelines and infrastructure of the ‘fuel-energy complex’.footnote43 But if anything, the opposite seems to be true: the skewed allocation of hydrocarbon revenues has propelled select parts of Russia—above all Moscow and the oil-producing areas of West Siberia—into hyper-modernity, while large swathes of the country are not only excluded from the circulation of goods and cash, but still lack access to running water and gas lines. In 2002, for example, 30 million out of Siberia’s population of 32 million were not provided with gas, which was of course being exported to the West in large quantities.footnote44 Much of the country remains seemingly stuck in a pre-modern infrastructural condition, while the capital and a few other cities bathe in the ether of wireless internet, to the sound of passing Mercedes and bmws.

The widening of geographical disparities coincided with continuing sectoral differentiation of the population by income. Table 4, below, shows average wages by sector across the economy, and indicates that agriculture, textiles and education fell further behind the average than they had been in the early 1990s, while banking, oil and gas remained far above it. These are average figures for each sector; within each sector, ever-greater differentiation was taking place according to the employment hierarchy. Table 5, also below, shows wages according to occupational categories which map fairly closely onto those used in Table 1 for the Leningrad machine-building plants. Whereas in the 1960s management earned only 1.7 times as much as unskilled workers did, by 2007 that multiple had risen to 3.9. Note also that many of these categories of workers earn not just less than the average, but significantly less—under half, in the case of unskilled workers. Official statistics do not capture the considerable numbers of undocumented migrant workers, predominantly from Central Asia, who make up a much larger pool of unskilled labour; thousands of Tajiks, Uzbeks, Kyrgyz and others toil on construction sites or clean the streets of Russian cities for abysmal wages—or even no payment at all, since foremen often tip off migration officials to ensure workers are expelled once projects are completed.

Alongside this growing ethnic segmentation of the workforce, the gulf between the incomes of men and women was also maintained, or even widened. By 2009, female unskilled workers as a whole earned only 58 per cent of the average wage, and in some sectors unskilled women earned far less than this—34 per cent in education, 41 per cent in healthcare; though unskilled men in these sectors were also underpaid. The largest differentials between men’s and women’s earnings are at the top end of the occupational hierarchy: whereas male managers on average earned 220 per cent of the average wage, female managers earned 150 per cent—a gap of 70 per cent.footnote45 Again, socio-occupational wage differentials were accentuated still further by sectoral variations.

The figures cited above for managerial earnings are averages which scarcely reflect the sums raked in at the upper end of this layer: in 2010, board members of Gazprombank earned $2.9 million on average and those of Sberbank $2.4 million—400 and 325 times the national median wage respectively.footnote46 The processes of elite super-enrichment that marked the 1990s continued unabated in the 2000s. Indeed, by the end of the decade, according to the Forbes Rich List, the country had produced a hundred billionaires, and Moscow had more than any other city in the world. The complexion of this elite had altered somewhat since the heyday of the oligarchs, many of whom had been brought to heel or chased from the country by Putin after 2000. The financial sector, badly damaged by the rouble crisis, lost ground as mineral resources came to predominate, especially with the increases in global commodity prices spurred by China’s rise. Figures such as Berezovskii and banker Vladimir Gusinskii departed the scene, replaced by the likes of aluminium magnate Oleg Deripaska; Aleksei Mordashov, owner of steelmaker Severstal; and Alisher Usmanov, owner of iron, steel and telecoms companies as well as the business daily Kommersant.footnote47

In parallel with this recomposition of the elite came a reconfiguration of relations between state and business. The economic rebound after 1998 had laid the basis for a recovery of state capacity, which after 2000 enabled a much strengthened executive to forge a consensus with the elite on its own terms. The ranks of biznes and political elites were increasingly interwoven, at national and regional levels, in a compact that underwrote the political stability of Putin’s first two mandates. The war in Chechnya and curbing of regional governors’ powers were territorial expressions of his project of restoring the ‘vertical of power’. In other spheres, the return of state authority meant a resumption and extension of Yeltsin’s programme of liberalization—for example in the tax reform of 2000, which imposed a highly regressive flat income tax of 13 per cent, and lowered the ‘social tax’ on employers. These boons to business were complemented by moves to liberalize the labour market—a new Labour Code was adopted in 2001—and later by reforms to housing services and the system of in-kind benefits (l’goty). The latter measure, adopted in early 2005, prompted widespread resistance, as pensioners, former military personnel and others marched in dozens of cities to protest the monetization of transport, medication and other benefits. The surprising scale and geographical extent of the mobilizations prompted the government to increase the compensation offered. Though the protests tailed off, this was the first time since the 1990s that popular discontent had spilled onto the streets in large-scale, collective form; an early sign of a possible renewal of Russian society’s potential for contestation.

Middle or majority?

The period of ‘stabilization’ after 2000 brought a recurrent emphasis on the emergence of a ‘middle class’—seen both as the inevitable product of better economic times and as a reliable yardstick of progress towards the norms of the advanced capitalist world. Western reporters noted the spread of sushi restaurants and home-furnishing stores, and counted the number of imported cars parked at the foot of Moscow’s apartment buildings, signs of the existence of the class that would form the bedrock of liberal democracy. More recently, as noted earlier, this emergent middle class has been hailed as the animating force behind the anti-Putin demonstrations. But is there a sociological reality behind these ideological mirages? The empirical evidence is puzzling, to say the least. A number of Russian sociologists have sought to gauge the size of the middle class, according to a variety of overlapping measures: income and material well-being; levels of education and occupational status; and the purely subjective criterion of self-identification. The results vary extraordinarily. Tatiana Maleva gives the size of the middle class as 21 per cent, if we look at material well-being; 40 per cent according to self-identification; 22 per cent by level of education; but only 7 per cent if we require all three criteria to overlap.footnote48 Natalia Tikhonova uses similar criteria and combines them to find a middle class that comprises 20 per cent of the population. Olesia Yudina gives figures of 29 per cent according to educational and occupational criteria, 29 per cent by quality of housing, 80 per cent by self-identification, but only 9 per cent if all three criteria are applied. Liudmila Khakhulina similarly finds that 80 per cent of the population consider themselves to be middle class.footnote49

Depending on the criteria, then, Russia has a middle class that consists of somewhere between 7 and 80 per cent of the population. What is going on? Several factors seem to be in play here. First there is the concept of the ‘middle class’ itself. In Keywords, Raymond Williams noted a distinction between notions of class as social rank and as the expression of an economic relationship; ‘middle class’ originally referring to a location within the social hierarchy of pre-Industrial Britain, whereas the concept of a ‘working class’ emerged during the Industrial Revolution to describe those who lived from their labour.footnote50 This distinction has often been blurred, but it sheds light on the dwindling of class identification in recent decades. For the main form of identification that has been waning is that of the working class, as the economic relationships that marked it out from the rest of society have been dissolved or reconfigured. The same processes have been underway in Russia, and their impact has been all the greater because industry was such a dominant part of the Soviet economy. The material downgrading of the working class has been accompanied by an ideological assault which has brought what Karine Clément has called a ‘desubjectivation’ of workers, who have internalized the opprobrium heaped on the system that had so promoted the image of the worker.footnote51

In these circumstances, many have sought to identify themselves with what is clearly the ‘leading class’ according to the new ideology. It is noteworthy that many definitions make it relatively easy to ‘join’ the middle class: the state insurance company, Rosgosstrakh, has defined it as consisting of those able to buy their own car.footnote52 This leads us to a second consideration: the nature of Russian consumption. For as a visit to the spalnye raiony—the ‘sleep regions’ or suburbs—of any major city will tell you, consumption here often focuses on conspicuous items such as cars or phones rather than, say, investment in a better apartment. This is partly dictated by the general degradation of the housing stock and the relative scarcity of mortgage financing, putting new apartments beyond the reach of most. But it is also related to a need to prove membership in a community of consumption. Indeed, for many it is consumption itself that seems to define middle-classness in Russia today. Returning to Williams’s distinction, we might say that ‘middle class’ denotes a broad stratum of consumers within the country’s socio-economic hierarchy, rather than any actual class identity.

A third factor also needs to be borne in mind. For alongside the new social categories and distinctions that have emerged in Russia, remnants of the previous social order have survived. This is true both in the realm of consciousness and in material reality: pensioners bearing portraits of Stalin co-exist with teenagers wielding iPhones; beyond the skyscrapers and designer boutiques of Moscow lies a land strewn with Soviet industrial enterprises. This is what might be termed ‘combined and uneven social development’: the coexistence and interpenetration of different socio-economic systems, and therefore of multiple schemas of social identity and forms of lived experience. One of the effects of this overlapping of two social orders may have been to expand the size of the potential ‘middle class’, by enabling whole sectors of Russian society to interpret their position within the new capitalist system according to the categories of the Soviet one. Skilled workers, for example, would have been located somewhere in the middle of the Soviet status hierarchy; but in the new hierarchy established after 1991, the status of manual work is increasingly downgraded (with sectoral exceptions for oil and gas). However, the lingering residues of the Soviet social framework, and the persistence in many areas of its physical realities, have partly obscured these shifts in standing, allowing many to continue to perceive themselves according to the old schema. In other words, to see themselves as ‘middle class’ when they are in fact part of the majority excluded from that ‘class’ by most empirical measures.

This overlapping of social structures is among the keys to explaining why post-Soviet Russia has been so relatively stable. The closure of the political system and the need for many people to focus on mere survival were obviously crucial, as was the overall quiescence of an atomized industrial labour force. But alongside these factors we should also weigh the coexistence of the two social structures, which has served to mitigate the force of what would otherwise have been a still more traumatic process in which one simply displaced the other. In that sense, we need to invert the arguments often made by free-market liberals that Russia’s ‘transition’ has been hampered by holdovers of the Soviet past.footnote53 Rather, it was the residual social forms of the ussr that enabled its capitalist successors to consolidate their rule, providing them with an invaluable social ‘subsidy’. In his first and second presidencies, Putin benefited from a long run of high oil prices. He was also fortunate in a deeper historical sense, taking the helm in a context of dramatic polarization, but where the coexistence of old and new social structures allowed some of the consequences of this polarization to be blurred. How long would this world-historical luck last?

IV. THIRD PHASE

A new phase of Russia’s post-1991 social development began with the global economic crisis, which clouded the scene just as President Medvedev, Putin’s hand-picked successor, took office. As in the West, the initial shock came in the realm of finance, with the onset of the credit crunch: in the six months to October 2008, the rts stock market lost almost three-quarters of its $1.4 trillion capitalization.footnote54 Tightening credit conditions and overstretched corporate balance sheets were then compounded by the slump in global demand, which brought sharp drops in output, especially in metallurgy and manufacturing—the latter experiencing a 25 per cent fall in the year to Spring 2009. Automobile production was among the worst affected: output dropped by 60 per cent in 2009.footnote55 Given that hydrocarbons may account for as much as 30 per cent of the country’s gdp, it is not surprising that the vertiginous decline of oil prices—from $130 a barrel in July 2008 to $40 that December—also had a severe impact. Overall, Russia experienced the steepest contraction in the G20, going from a growth rate of 8 per cent in 2008 to a contraction of 8 per cent in 2009.

The drastic downturn brought a wave of factory closures and unemployment, which hit 10 per cent by April 2009, the same rate as after the 1998 rouble crash. But it also saw the return of crisis phenomena from the 1990s: barter transactions, under-the-table cash payments, shortened hours and unpaid leave, as well as non-payment of wages; by May 2009, an estimated 38 per cent of the population was affected by wage arrears. By the first quarter of 2009, 17 per cent of the population had incomes below the official subsistence level, a 25 per cent increase on the previous year. Poverty was principally concentrated in small towns and rural areas: according to official figures, in 2010, the latter accounted for 40 per cent of those living below the subsistence minimum, while 25 per cent lived in towns with populations under 50,000.footnote56

The government’s response involved some increases in social spending, pensions and unemployment benefits. There was also, notably, a 30 per cent wage hike for employees of the government or of state-affiliated companies; known colloquially as biudzhetniki, these by now comprised some 25 per cent of the workforce—a sizeable pool of supporters whom the Medvedev administration was keen to insulate from the worst of the crisis. The bulk of the government’s efforts, however, were directed to easing the cares of business: $200 billion was spent bailing out banks and leading Russian companies—notably those owned by favoured oligarchs, whose hard currency loans had been recalled. Meanwhile as much as a third of Russia’s accumulated currency reserves was used to defend the value of the rouble. All told, the Kremlin spent the equivalent of 13 per cent of gdp shoring up the economy—in proportional terms, a bailout twice the size of Obama’s.footnote57

In late 2008 and early 2009, there were demonstrations attacking the government’s handling of the crisis—small-scale, short-lived and geographically dispersed, but notable in the new severity of their criticisms of Putin and Medvedev. There were also wildcat actions: in the spring of 2009, the population of Pikalevo in Leningrad region blocked the highway between St Petersburg and Moscow to protest unpaid wages at the aluminium plant; Putin intervened personally to force its owner, metals oligarch Deripaska, to pay the arrears. Elsewhere, plant closures would also mean the death of entire towns: Russia contains as many as 400 ‘monocities’, where a single enterprise accounts directly or indirectly for most employment. The largest is Togliatti, with a population of 700,000, where the government moved swiftly to bail out the stricken car-maker Avtovaz in March 2009; many other monocities have not received such aid, and limp on by whatever means they can. As in the 1990s, both government and enterprises have sought to minimize overt unemployment, in order to stave off a still greater socio-economic breakdown.

It was in this context of spreading deprivation and continuing stagnation that the country entered its latest electoral cycle. Discontent with the corruption of the United Russia party, dubbed the ‘Party of Crooks and Thieves’, now came into the open amid a spreading disillusionment with the reigning system brought on by the economic downturn. There was also frustration in some quarters at the regime’s evident incapacity to implement any kind of ‘modernization’—a set of basic necessities that became the empty slogan of Medvedev, himself a token president. Putin’s announcement that he would run for the post again in 2012 effectively promised at best a decade of stasis—a prospect that was enough to galvanize a broad array of groups and currents of opinion.

‘You can’t even imagine us’

The demonstrations that followed the Duma elections of December 2011 were surprising in their size, geographical spread and ideological span. If their immediate trigger—electoral violations—brought echoes of the 2003–05 ‘Colour Revolutions’ in Georgia, Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan, their inclusivity and style of organizing had more recent precedents, in the Occupy movements and Europe’s indignado protests. A banner held by anarchists in St Petersburg seemed to encapsulate the ironic tone of the protests as well as the discrepancy between the regime and the society it ruled: Vy nas dazhe ne predstavliaete, meaning both ‘You don’t even represent us’ and ‘You can’t even imagine us’.

But beyond the ideological diversity, what has been the social make-up of the protests? Despite an overall sense of social heterogeneity, the main weight of the movements seems to have been urban, educated and broadly liberal. A survey of the miting on Sakharov Avenue on 24 December, for example, found that 62 per cent had a higher education degree, 46 per cent gave their occupation as ‘specialist’, and 31 per cent described their political affiliation as liberal.footnote58 This profile is comparable to that of the perestroika-era mass intelligentsia; indeed, those attending the recent marches may be the continuation of that cohort as much as their successors: 45 per cent of those surveyed at the rally were over the age of 40. The personal circumstances of the marchers, too, reflect the long-term reduction in means of this layer: 21 per cent said they could afford essentials, but not more expensive items such as a tv or a fridge; 40 per cent said they could not afford a car—thus, according to one yardstick noted above, debarring them from membership of the ‘middle class’ whom so many Western analysts saw as the mainspring of the movement.

However, the oppositional mobilizations thus far seem not to have possessed a broader mass base. The counter-rallies organized by the Kremlin in support of its candidate—notably a mass gathering on 23 February in Moscow’s Luzhniki stadium—may well have been facilitated by threats or payments to attendees; but the sociological distinction between those who gathered here and at the anti-Putin rallies is unmistakable. One account described a ‘grey, irritable crowd’ consisting of ‘workers—men in leather jackets with simple, reddish faces, and women in cheap fur coats’; whether employees of state enterprises or ‘poor biudzhetniki’, they represented that ‘downtrodden group of people, shorn of their dignity, who used to be called the “working class”.’footnote59 However appealing the opposition’s slogan of ‘honest elections’ might be in the abstract, the increased vulnerability of these social groups during the crisis—and their memories of the suffering that the 1990s turbulence brought them—may have made the certainty seemingly offered by Putin preferable to any upheaval.

A further reason why the opposition was unable to attract broader mass support may have been the fact that it could not offer a positive alternative programme—only the hopeful negation of a ‘Russia without Putin’. In concrete political terms, the immediate goal was still more modest: to prevent Putin winning a majority in the first round. According to the official results, the only place where this happened was in Moscow, where he scored 47 per cent. Even allowing for a considerable margin of fraud, he would still have secured a return to the Kremlin in a hypothetical second round. The opposition that so recently began to coalesce has thus already met with one resounding defeat. With Putin reinstalled as president for the next six years at least—and with the existing political structures seemingly impervious to its demands—the question inevitably arises of where the opposition should now focus its attentions.

So far the emphasis of the mobilizations has fallen overwhelmingly on the political form of the regime, and on Putin himself as its figurehead. Criticisms of its social substance—dizzying inequalities, deep deprivation and exploitation, ongoing degradation of public services—have been much less prominent, which is surely a factor in the movement’s inability thus far to obtain fuller resonance. One potential path towards acquiring this would be for the anti-Putin opposition to connect their formal demands about the democratic process to the injustices built into the broader social landscape. In view of the sociological make-up of the protests to date, this seems a doubtful prospect. Yet it is on this terrain that the struggle for Russia’s future may unfold: the present crisis conditions seem likely to bring the further spread of unemployment and ever greater inequalities, spurring discontent in a variety of social sectors and geographical areas. Amid a global economic slowdown, in which reduced oil revenues and earlier spending on anti-crisis measures have placed increased strains on the government budget, Russia’s rulers will be confronted by a widening range of social problems that the system in its current incarnation is not built to even address, much less resolve.

Putin’s second spell in office begins in very different circumstances—political, economic, historical—from his first. The good fortune of high commodity prices and post-1998 rebound has evaporated, and the system of ‘managed democracy’ over which he presides seems increasingly inadequate to the tasks of governing such a large and diverse country, with such large and diverse problems. The regime has survived its most recent scare, and may yet escape from others. But there is one outcome it will not be able to evade, and which may pose a greater peril to it in the long run. The parallelism of social structures noted earlier, which has underwritten the relative stability of post-Soviet Russia, cannot hold indefinitely. The ‘subsidy’ to the present from the Soviet past depends on the continued presence of people who remember the ussr, and who can still to some extent inhabit its realities. As the years pass, their numbers will dwindle until they no can longer provide an inertial social basis for stability; and as their weight within the population declines, so the prominence will increase of those whose lives have been shaped entirely by the new capitalist order.

This is, of course, exactly what the liberal reformers of the 1990s wished for—a cohort of New Russians untainted by Sovietness, entirely socialized within the market. But there could be a historical irony lurking here: as the social consciousness of the Communist era fades, the succeeding generations may search out other forms of commonality rooted in their experience of contemporary capitalism. The very success of the implantation of the market, indeed, will provide the basis for new forms of collective defiance. Signs of this began to emerge in a variety of realms after 2005, as many Russians sought to resist deepening marketization and ecological depredation: there have been local struggles over housing and communal services, in the wake of their liberalization in 2005; actions over environmental issues, including attempts to block a proposed motorway through Khimki forest outside Moscow in 2010; and not least new forms of labour activism, with the spread of independent trade unions in foreign-owned car plants since the mid-2000s.footnote60 It is perhaps within this variegated, plural realm that possibilities for another sequence of historical transformation in Russia will ultimately lie.