Fourteen years after Labour crashed to defeat, amid failing banks, soaring unemployment and grinding foreign wars, it has been returned to power under a hatchet-faced leader with an unassailable majority: 411 out of 650 mps. On the face of it, the gales of discontent that blew with such force through the British political system in the 2010s—Scottish independence, Corbynism, Brexit, parliamentary uproar, Irish crisis, revolving door at Number Ten—have subsided into centrist zephyrs, propelling the ship of state serenely forth. As many have pointed out, however, Labour’s win on July 4 was a ‘seat-slide’, not a popular-vote tsunami: 63 per cent of the Commons obtained with only 34 per cent of the ballots—a record skew.footnote1 How should the character of the vote—and the condition of the country—be understood?

Three initial points should be made about the 2024 popular vote. First, there was no swing to Labour. On the contrary, Labour’s vote fell by half a million, from Corbyn’s 10.3 million in 2019 to Starmer’s 9.7 million. If Labour’s percentage registered a tiny positive swing of 1.6 per cent, this was an effect of falling turnout: down by 7.5 points, from 67.3 per cent in 2019 to 59.8 per cent this year—the poorest showing since Blair’s re-election in 2001 on a 59.4 per cent turnout, itself a historic low. Starmer’s Labour received the votes of only 20 per cent of the overall British electorate—a worse result than Blair’s 22 per cent in 2005, in the trough of the Iraq War, and the lowest vote-share that a majority Westminster government has received since the introduction of universal suffrage. The prevailing sentiment was a dogged anti-incumbency. Asked why they intended to vote Labour, 48 per cent responded, ‘To get the Tories out’ and 13 per cent that ‘The country needs a change’. Only 5 per cent cited Labour’s policies.footnote2

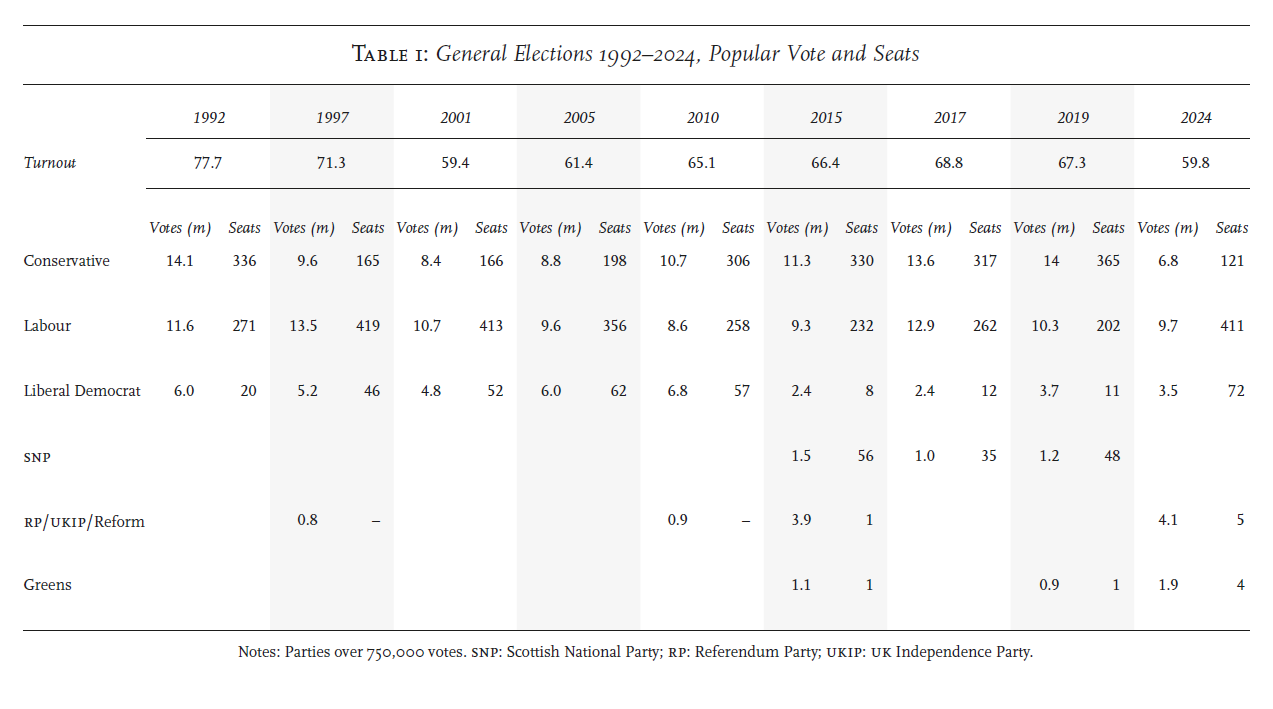

Second, Labour’s victory was the product of an unprecedented Conservative collapse: the desertion of over 7 million of the 14 million voters that had backed Boris Johnson’s call to ‘Get Brexit Done’ in 2019. This was a significantly greater slump than the Tory debacle of 1997, when the long spell of Thatcher–Major rule capsized with the loss of 4.5 million votes; let alone the relatively modest decline of 1.7 million votes that put an end to thirteen years of Tory rule in 1964. Notably, the Conservatives’ meltdown this year followed several rounds of steady increase since their return to office in 2010 after New Labour’s fall. The Tory vote had climbed from 10.7 million in 2010, to 11.3 million in 2015, after five years of austerity, and 13.6 million in 2017, in the aftermath of Brexit, to its 14 million peak in 2019. This year they lost 251 seats, clinging on to just 121—another post-war record low; even after Attlee’s landslide in 1945, the Conservatives held 197 seats; after Blair’s in 1997, they held 165 (see Table 1).

Third, it was a different story in Scotland and Northern Ireland. Scottish voters did swing to Labour, which gained some 300,000 votes to win a plurality of 852,000, its best result north of the border since 2010; but this was well below the 500,000 Scottish National Party defectors and abstainers. Combined with 400,000 Scottish Tory deserters, snp stay-at-homes brought the Scottish turnout down to 59 per cent, from 68 per cent in 2019. The snp’s Westminster seats slumped from 48 to 9, while Scottish Labour’s seats rose from one to 37. Yet the swing was due rather to snp voters’ justified fury with the corruption and mendacity of the Sturgeon leadership than affection for Starmer.footnote3 Support for Scottish independence still runs at 45–48 per cent, but Sturgeon and her husband have scuppered any unified political expression of that outlook for some time to come. In Northern Ireland, which has an entirely different party system to that of mainland Britain, the molecular process of Irish reunification that gained a forward jolt from Brexit advanced another millimetre in 2024 due to deep divisions in the part demoralized, part lumpen-radicalized Unionist and Protestant ranks.footnote4

Class shifts

What explains the scale of the Tory collapse? The electoral drivers were three-fold. The right-nationalist Reform uk took 4.1 million votes, 14 per cent of the ballots cast, with an estimated cost to the Conservatives of eighty seats.footnote5 In over 170 of the seats the Conservatives lost, the Reform vote was greater than the margin of their defeat.footnote6 Nigel Farage’s latest vehicle featured a largely negative manifesto—anti-immigration, anti-corporation tax, anti-public spending, anti-net zero; pro-army—and down-played its supposed commitment to constitutional reform. Its principal function in the 2024 election was as a protest vote for Leave supporters to register their rage and disappointment at the outcome of Brexit in Tory hands—mapping onto the depressed regions and run-down towns in Eastern England, the Midlands and the North whose discontent took the uk out of the eu. Among working-class Leave voters, in particular, support for the Conservatives plummeted, with over half turning to Reform.footnote7

In constituency after constituency, from North West Cambridgeshire to Bolton West, Lowestoft to Dartford, the combined Tory–Reform vote towered over Labour’s. If Starmer’s aim in purging Corbyn and his supporters, adopting Conservative spending plans and extolling ‘patriotic values’ was to reinflate Labour support in Northern and Midland rustbelt communities, it fell flat. Labour’s vote-share across these ‘red wall’ seats rose by just 3 points; decisive was the 24-point drop in Conservative support.footnote8 In Bolsover, on the disused Derbyshire coalfield, Labour overturned a Tory majority of 5,000 despite adding only 600 votes to its tally for 17,000 in all, compared to 10,900 for the Tories and just over 9,000 for Reform. Similarly in Dudley in the Black Country, Labour emerged victorious with just 12,000 votes on a 51 per cent turnout; the Tories were reduced to 10,300, while Reform took 9,400. Five years earlier, with no Farage party in play, Johnson’s Conservatives had romped to victory in the predecessor Dudley North constituency with over 23,000 votes. All in all, Johnson had taken 28 of the working-class ‘red wall’ seats in 2019, and Corbyn ten; in 2024, Labour took 37 of them while one, Ashfield, went to Reform.

To the lethal effect of Reform should be added Conservative abstentions, estimated to have cost the party another 33 seats, and systematic Labour–Liberal Democrat tactical voting.footnote9 In London commuter-belt seats like Hertford and Stortford, where Labour had finished a fairly strong second to the Conservatives in 2019, one in four Liberal Democrats lent it their votes. Where the Liberal Democrats were so placed, one in three Labour supporters switched.footnote10 Although the Liberal Democrats’ popular vote actually fell from 3.7 million in 2019 to 3.5 million in 2024, anti-incumbent tactical voting increased the number of Liberal Democrat MPs sixfold, from 11 to 72, capturing seats across affluent southern England, from St Ives in the far west through the Cotswolds to Guildford, Winchester and Tunbridge Wells, also running Chancellor Jeremy Hunt close in leafy Godalming, Surrey.footnote11

Many of the high-profile Tory casualties in 2024 were victims of all three factors: Reform, abstentions and Lib–Lab tactical voting. In Portsmouth North, a working-class bellwether with a strong Royal Navy presence, support for the Conservative incumbent, Leader of the House Penny Mordaunt, halved from 28,000 in 2019 to 14,000. Reform took 9,000 votes, turnout fell below 60 per cent and Labour edged to victory by less than 800 votes. Another high-ranking Tory casualty, Defence Secretary Grant Shapps, relinquished a majority of 11,000 in Welwyn Hatfield, twenty miles north of the capital. His support fell from 27,000 in 2019 to 16,000—Reform doing most of the damage, attracting 6,000 votes—while Labour’s vote climbed from 16,000 to 20,000, helped by crossovers from the Liberal Democrats, whose vote fell by the same amount. Lib–Lab voting plundered the Conservatives’ hoard of 43 ‘blue wall’ seats in southern England, with their wealthy, university-educated Remain voters; in 2024, the Liberal Democrats took 23 of these and Labour nine, leaving the Conservatives with just eleven.footnote12

Countering this double class-pincer movement—working-class desertion of the Tories in the Midlands and North; middle-class Lib–Lab unity in the more prosperous South; both to Labour’s benefit—there was a small but potentially significant radical rejection of Starmer’s party. Breaking through Westminster’s protective wall of disproportional representation, the Greens won four seats, coming fifth with 1.9 million, 6.7 per cent of the popular vote. This was above all a youth vote: though gaining among the elderly, Labour lost ground among the under-40s, especially women under 35, whose support dropped by 9 points compared to 2019, while Greens won 14 per cent among 18–24s.footnote13 Overall the Greens attracted 10 per cent of 2019 Labour voters, unseating Shadow Culture Secretary Thangam Debbonaire in Bristol Central and holding off Labour in Brighton Pavilion, while also securing two rural seats on England’s western and eastern margins in face-offs against the Conservatives.

Labour also lost votes in urban constituencies with large numbers of Muslim voters protesting against Starmer’s backing for Israel’s genocidal assault on Gaza. The Labour leader had said four days after October 7 that Israel had the right to withhold power and water from Gaza and then whipped Labour mps not to support an snp motion for an immediate ceasefire, prompting ten frontbenchers to rebel and scores of local councillors to quit.footnote14 Four pro-Gaza Independents were elected, alongside former Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn in Islington North with 24,000 votes, after Labour’s National Executive Committee barred his candidature on Starmer’s instructions. Starmer himself shed 10,000 votes to the Greens and to pro-Gaza, former anc militant Andrew Feinstein in his Holborn and St Pancras constituency. The biggest upset for Labour on the night came in Leicester South in the East Midlands, where Shadow Cabinet member and Labour attack-dog Jonathan Ashworth was defeated by Independent Shockat Adam, who declared the win was ‘for Gaza’. In Ilford, Essex, Labour’s normally bullish Health spokesman Wes Streeting clung on against another independent challenger by just 500 votes.footnote15

Western discontents

Beneath the Labour seat-slide, the 2024 election reveals deeper—in some respects, countervailing—class-related shifts. Once again, the post-industrial English working class has proved itself capable of putting a strong inflection on the national outcome, as it did in the 2016 eu referendum, without achieving any real improvement in its relative position or even any advance for its immediate ‘corporatist’ interests.footnote16 At stake here is the wider impasse of post-imperial Britain, with parallels across the advanced-capitalist societies of the West—a discontent that manifests itself in high negative scores in answers to the pollsters’ question: ‘Is the country headed in the right direction?’.

As elsewhere in Europe, the uk has seen a precipitous decline in the popular vote for its twin parties of government, hollowing out the alternating bi-partisan Westminster system. In Germany, from reunification through to 2005, over 60 per cent of the overall electorate voted for the mainstream parties, cdu–csu, spd, fdp; that dropped to 50 per cent in 2009, as workers deserted the spd amid the desolating effects of the Hartz reforms and the Grand Coalition. In 2017 and 2021 it hovered around 45 per cent, with the rise of the afd. In France, the decline has been much steeper. In the second round of the French legislative elections, around 50 per cent of the overall electorate cast a vote for centre-left or centre-right parties through the 1990s and 2000s. That fell to 42 per cent in 2012, with the onset of the Eurozone crisis, then plummeted to barely 20 per cent after 2017, as Macron’s vehicle cannibalized the ps. In Britain, around two-thirds of the electorate cast a vote for one or other of the parties of government through to the 1990s. In 2001, it dropped to 43 per cent, as the Northern working class abandoned Blair’s New Labour. Recovering briefly to over 50 per cent for the two Brexit elections of 2017 and 2019, it plunged again this year to 33 per cent.

But each discontented nation-state is discontented in its own way. Britain emerged from the Second World War indebted and exhausted, but institutionally intact. Government and empire limped on, absent the modernizing shocks of military defeat and constitutional re-foundation that helped to re-charge growth rates in Germany, France and Italy. The uk remained a low-investment economy with an overblown financial platform in the City of London and a declining industrial sector, based on coal and steel—of secondary interest to the ruling class, so many of whose investments had been overseas since the 1850s, but of prime importance to the mass of English, Welsh and Scottish workers, who built dense cultural barricades around their class positions. Breaking these down became the order of the day for post-war Westminster and Whitehall.

After two initial attempts at modernization—Wilson’s ‘white heat of technology’ drive (1964–70) and Heath’s proto-neoliberal Europeanization (1970–74)—were stymied by fiscal exhaustion and trade-union resistance, Thatcher on the third try opted for all-out confrontation with the labour movement. Beginning with the defeat of its most intransigent sectors—miners, steel, engineering—she proceeded systematically through the rest, while sapping the ‘municipal socialism’ of working-class districts through compulsory council-house sales, slashed revenues and centralized budgets. The Opposition under Neil Kinnock threw its weight behind this revolution from above with a ferocious attack on the left.

Under Blair and Brown, New Labour bought into the Thatcher solution to Britain’s post-imperial crisis, adopting and owning it. Blair tried to prove that a lieutenant’s role in the us thrust into Eurasia would ensure Britain’s high standing in the world—a project that foundered in the backstreets of Basra, the graveyards of Helmand and the torture chambers of Guantánamo. Brown tried to show that a low-wage service-sector economy harbouring a hypertrophied financial district could, through crafty taxation, ensure social-welfare crumbs for children in need and guarantee high returns to private capital from public-sector investment. This over-leveraged contraption came crashing down in the 2007–12 financial crisis, leaving only stagnant wages, rising housing costs, vertiginous regional inequality and flat-lining productivity. After New Labour’s overwhelming defeat in 2010, the Liberal–Tory coalition under Cameron and Osborne imposed austerity, cynically shielding the Conservatives’ pensioner base while punishing those dependent on disability and child benefits, above all in the small-town Midlands and North.footnote17

Post-crash stagnation

In some respects, Britain was the worst placed among oecd countries to weather those storms. The economic model Thatcherism had installed—finance deregulated, public assets privatized, industrial centres shut down, interest rates and unemployment pegged high, to defang the unions—concentrated growth in the South, setting in train the regional divergences in income and productivity rates that have become the starkest in the oecd. In the 1980s, London’s productivity rate was 128 per cent of the national average; by 2024, it was 170 per cent—and, tellingly, the other major cities’ productivity now lagged below the national rate. In terms of economic development, the model had produced ‘a hub with no spokes’, centred on the capital.footnote18 Nevertheless, buoyed up by the bubble of financialized globalization, uk aggregate growth rates kept up with or even surpassed those of its peers throughout the 1990s and early 2000s.

That changed with the 2008 crash. Since then, the uk has entered a period of marked economic decline compared to other G7 and oecd countries. British productivity grew at 4 per cent between 2007 and 2022, below France (6 per cent), Germany (11 per cent), Canada (12 per cent), the us and Australia (18 per cent). Sluggish growth and high regional inequality were compounded by plummeting investment after the financial crisis. In 2005, the uk’s business investment was 11 per cent of gdp, level-pegging with France; by 2022, the French rate had risen to 14.8 per cent, while Britain’s had dropped to 10 per cent—again, among the lowest in the oecd.footnote19 British median household income stagnated after 2007, overtaken by Germany and France and falling further behind Australia, Canada and the us. In the uk, growth in real wages fell below zero after the financial crisis; they have yet to recover their 2008 level. After forty years of deepening social inequality, low-income households in Britain are now 27 per cent poorer than their French and German counterparts. Since 2007, Britons have also been working longer hours than their oecd peers, to make up for stagnating wages.footnote20 Public investment fell, in line with growth rates: in real terms, education spending per student fell by 9 per cent between 2010 and 2020. The number of uk hospital beds shrank from 2.76 per thousand in 2013 to 2.42 in 2021, compared to 7.76 in Germany and 5.65 in France.footnote21

To its supporters, Brexit offered a solution of sorts to this long-running crisis; to its opponents, a disastrous deepening of it. Predictably, Brexit failed to resolve the social sources of class and regional discontent. The promise of sovereignty, once free of the eu’s supra-national regulatory fora, failed to acknowledge the other, more powerful extra-national economic and political interests that helped to shape the uk’s social order through its native governing class. Brexit did not offer an alternative political-economic programme; it had no social content. The Brexiteers wagered that social and economic reforms would follow constitutional disengagement from the European Treaty. They did not. No sooner had establishment opposition to Brexit been silenced by Boris Johnson’s 2019 election victory than the gestures towards regional ‘levelling up’, advocated by Johnson, Cabinet colleague Michael Gove and special adviser Dominic Cummings, collided with the global emergency of the Covid crisis. Brexit only worsened the trade frictions, labour shortages, broken supply-chains and surging inflation to which the world economy was then subject.

By 2022, Johnson’s support had been eroded by his erratic mismanagement of the Covid crisis, coupled with a drip-feed of revelations from top civil servants of lockdown-busting social gatherings in Downing Street: one aide wheeling a suitcase of alcohol down Whitehall; the government’s ethics adviser hauling a karaoke machine to a staff party. Ousted by a revolt of Tory ministers, Johnson was succeeded in September 2022 by Liz Truss, whose premiership coincided with the onset of double-digit inflation—the uk suffering the highest, longest bout of any G7 country. Truss self-immolated by introducing deficit-funded tax cuts on top of emergency household-energy subsidies, following her war of words with the Bank of England and dismissal of the top civil servant at the Treasury; she was defenestrated by doubting bond markets within six weeks of taking office. Her successor, Rishi Sunak, donned a fiscal straitjacket to reassure the markets—Britain’s wealthiest-ever Prime Minister presiding over the cost-of-living squeeze. The 2022–23 strike wave of rail and postal workers and public-sector professionals stood comparison with the 1960s for the number of days lost to industrial action; impressive for a labour movement half the size it was then.

By now it was obvious that Brexit, which Sunak had supported, had yielded neither economic gains nor a check to immigration, which reached record levels in 2023; nor any democratization of Westminster, where Tory prime ministers, Cabinet re-shuffles and policy churn proceeded without reference to the popular will. Yet the dismal state of the economy and failing public services were probably decisive.footnote22 Over seven million people were languishing on waiting lists for hospital treatment, in a health service tipped over the edge by Covid backlogs and strikes; two million were too sick to work. Swimmers were falling ill with diarrhoea and vomiting through raw sewage discharged into rivers and coastal waters by debt-guzzling privatized utilities. Local councils were beginning to declare bankruptcy, among them Labour-run Birmingham, the largest municipal authority in Europe. Record delays in the criminal courts, where barristers have been protesting low pay and cuts to legal aid, meant prisons were ‘stuffed to the gunwales’.footnote23 By 2024, the cumulative impact on popular judgements of the Conservative regime was deadly.

Prospects under Labour

What sort of Labour government is now in charge? Unlike the American party model, with its loosely conjoined oligarchy of elected officials, mega-donors and media backers floating above the registered voters—or, for that matter, 21st-century electoral vehicles where an autonomous leadership accumulates supporters, as in Podemos, lfi, the Five Stars, bsw—Labour and the Conservatives still have 20th-century mass-party forms, with hundreds of thousands of dues-paying, door-knocking members. Their internal constitutions reflect contrasted origin stories. A Tory interest first began to distinguish itself in the 18th century as the ‘country party’ against the ‘court party’ of the ruling Whigs who, under the immensely corrupt Walpole, favourite of George I, were engorging themselves with colonial and slave-trading wealth. The two factions united against the banner of the rights of man lofted by the French Revolution, and came together again to crush the great popular-democratic movement of the Chartists in the 1830s. Little would differentiate the two ruling-class parties, Conservative and Liberal, that crystallized to structure parliamentary government over a slowly widening domestic suffrage and a mass of disenfranchised colonial subjects beyond it.

Through to the end of the Thatcher period, the Tory Party maintained an internal structure premised on Westminster’s imperial supremacy: an informal, self-reproducing group of grandees would steer the mps’ selection of a new leader; the local Conservative Associations were in principle autonomous, but by the same token could not organize together to determine the direction of the party. Only after Thatcher fell did it become clear how far the social bases of the old-gentry order had been undermined, without her putting any more democratic forms in their place. The Conservatives came under pressure to adapt to their actually existing mass membership: a shrinking cohort of right-wing middle-class pensioners, concentrated in the South of England and retirement-home seaside resorts, and a handful of ambitious young upstarts eyeing a political career.

It was the Liberal Party that sheltered the first trade-union mps, representing working-class voters in the great industrial cities from the 1880s. The Labour Party was late-born among the formations of the Second International, forcibly midwifed by the House of Lords’ ruling against trade-union action at Taff Vale in 1901, and formally constituted on the lines drafted by Sidney Webb only in 1920, a generation or more after the forging of the German, French and Russian parties. History has yet to overtake Tom Nairn’s famous anatomization of the Frankenstein’s monster produced by this amalgamation of a brain, led from Westminster, with the brawn of trade-union funding and the heart of the powerless individual members, recruited wholesale from the mild socialists and pacificists of the pre-existing Independent Labour Party.footnote24 This ramshackle arrangement has been maintained, with shifts in the direction of members’ rights in the 1980s and 2010s, followed by counter-moves as the right-wing leadership reasserted itself.

In government, Labour’s natural centre of gravity has always been firmly on the right, with intermittent lurches to the left in opposition in reaction to the outcome of its spells in office. From 1945–51, Attlee governed with a tight-knit Cabinet group which included Ernest Bevin, Herbert Morrison and Hugh Gaitskell but excluded loose cannons like Nye Bevan. Attlee could boast of 28 ex-public-schoolboys in his government, among them seven Etonians, five Haileyburians and four Wykehamists. The Keep Left group led by Ian Mikardo, which opposed the Cabinet’s Cold War policies and called for a European ‘third force’, was firmly consigned to the backbenches. The post-war Labour government sent troops to restore French and Dutch rule in Indochina and the East Indies, waged a counter-insurgency against the anti-colonial resistance in Malaya, stood by as Israeli militias drove three-quarters of a million Palestinians from their homes and oversaw a partition of the Subcontinent that left over a million dead. Attlee signed up for us military command over British forces in nato, welcomed us b-29 bombers and nuclear warheads to uk bases and schemed behind Parliament’s back to acquire ‘a British bomb with a Union Jack on it’. It was only in 1951, when Chancellor Gaitskell imposed charges on nhs dentures and spectacles to help fund a defence budget worth 14 per cent of gdp, including the dispatch of 80,000 British troops to back the Americans in the Korean War, that Bevan and Harold Wilson resigned from the government.

Wilson had sided with the Labour left in the 1950s, on and off, and as Gaitskell’s Shadow Chancellor his attacks on the archaic British system were intelligent and hard-hitting. His elevation to the leadership in 1963, a chance product of the virus that killed Gaitskell combined with a helpful split on the Labour right, was greeted with excitement by radicals; but as Ralph Miliband pointed out at the time, it left the Parliamentary Labour Party and Shadow Cabinet otherwise unaltered.footnote25 Ambushed by the markets, Wilson’s government waged inept class war on its own trade-union backers. Its lasting social reforms—gay rights, abortion, divorce—came from the liberal right of the party, under Roy Jenkins. Wilson squirmed under us pressure to send troops to Vietnam but resisted, though compensating with fulsome verbal support. It was only after the defeat of the final Wilson–Callaghan government in 1979, with its full imf austerity programme, that a deeper and broader challenge was mounted from the Labour left under the leadership of Tony Benn; Jeremy Corbyn was his dedicated lieutenant.footnote26 This threat to the social and political order was not reflected in any change to the Shadow Cabinet, around which ideological ranks inside and outside the party closed immediately—distancing Labour, too, from the epic militancy in the collieries and on picket lines that countered Thatcher’s onslaught. Neil Kinnock spent his ten years as Labour leader hammering what he and the tabloids described as Britain’s ‘looney left’.

From the mid-90s, Blair and Brown left the party’s internal management to Kinnockite henchmen while shifting the Shadow Cabinet well to the right. Governing with huge majorities, the Blairites essentially ignored Parliament and tolerated the 30-strong Labour-left Campaign Group as if they were so many eccentric relatives or elderly pets. A series of miscalculations then allowed Corbyn to run for the leadership in 2015, catching the winds of youthful discontent in an attractive left social-democratic sail. To the fury of Labour’s apparatus, parliamentary delegation and media, Corbyn provided a lead for the party well to the left of anything it had known before. Rather than being punished by the electorate, he was rewarded by a big upswing in Labour’s 2017 vote—necessitating the full onslaught of media and parliamentary smear campaigns.

The new PM

Starmer’s role in Corbyn’s Shadow Cabinet reflected a carefully plotted path to the top. Like Blair, he came from an ambiguous class background which seems to have helped fuel a powerful ambition. Born in 1962, he grew up in suburban Surrey, where his father ran a small tool-making business while his mother was a nurse; the school he attended went private, though he was allowed to retain a free place. Like Attlee and Blair, he trained for the Bar, though he read law at Leeds while they went to Oxford. Attlee, the son of a prosperous London barrister, was a staunch proponent of Empire and schoolboy jingoist for the Boer War, politicized along Fabian lines by doing charity work in the East End. Wilson, born in middle-class Huddersfield, was formed by the social-policy theorists of the 1930s and worked as Beveridge’s researcher. Blair’s formative influences were Christianity and rock ’n’ roll; he joined Labour as a calculated career move once he had established himself as a barrister and wanted to go into politics.

Starmer was formed ideologically by the atmosphere of the early Blair years when the British liberal intelligentsia, radicalized (mildly) under Thatcher, was moving into power and there was a modernizing buzz around notions of Europeanism and human rights. His voluminous European Human Rights Law (1999), published by a legal charity, reflects the times. But he found his feet working first at the Northern Ireland Policing Board (2003–07), then boycotted by nationalists for its partiality to the traditional Unionist constabulary, then the Crown Prosecution Service (2008–13). Again, he was protective of state-security operatives accused of torture or murder but his cps pressed Swedish prosecutors not to withdraw the case against Julian Assange and cracked down hard on teenage troublemakers. Notably he expanded the Director of Public Prosecutions job into an international role, frequently flying to Washington to consult with Eric Holder, Obama’s Attorney General, best known for drafting legal cover for the President’s drone strikes on civilians. He planned his entry into the Labour Party before leaving the cps, helped to a safe seat by Edward Miliband in 2015. Pressed to enter the leadership race after Miliband stood down, he refrained on the grounds that more experience was needed. Over the next four years, he set himself the task of acquiring it.footnote27

Unlike Blair, Starmer didn’t have a Kinnock when he took over the party in 2020. He needed to wipe out everything Corbyn had been and done at full speed. For this, he unleashed systematic vilification of his predecessor, expelling him from the party and expurgating what he had represented from its ranks, rewriting its rules to preclude any repetition of the glitches that had sporadically distorted its true path. Starmer’s grip on the party is now institutionally tighter—and more committed to a Washington-led capitalist world order—than anything Labour had known before. Paradoxically, his authoritarian drive has produced a liberating outcome for the left. In addition to Corbyn, the four pro-Gaza mps and four Greens, seven left-wing Labour mps were excluded from the Parliamentary Party within weeks of the election for refusing to back Starmer’s retention of the two-child benefit cap, a notorious Conservative austerity measure. The House of Commons has never before had a body of sixteen mps to the left of Labour.footnote28

Handed power on a plate by the debacle of the Tory Party at the fag-end of its rule, Starmer begins his mandate with a plenitude of power, in the combination of a sky-high majority in the legislature, and rock-bottom expectations in public opinion of any sudden improvement in the condition of the country. The result gives him considerable room for manoeuvre, letting him—in sticking closely to the fiscal legacy of Sunak—do as little as he wants without serious risk, since the disabused scepticism about the political class which lowered turnout at the polls this year is unlikely to fade quickly. In practice, however, he may want to make a display of energy and direction. There, he can draw on more assistance than afforded by his Shadow Cabinet, still partly a product of deals needed to assure a smooth transition away from Corbyn. Though civil servants were reportedly struck during pre-election access talks by Labour’s lack of a brains trust to do the heavy lifting on policy, a cluster of think tanks—the Institute for Public Policy Research, the Resolution Foundation, Blair’s eponymous Institute—will be furnishing cadres and spads.

Whether the ameliorative measures in preparation have much chance of redressing the long-term problems of the uk’s low-investment, low-productivity economy, now universally decried, is another matter. Neo-labourism offers no real historical explanation of them; the recipes offered by its leading lights—Bell, Hutton, Collier, Hindmoor and company—remain studiously banal.footnote29 Labour was tight-lipped before its entry into office, promising mainly to be more competent than its Tory predecessors—‘Change’, but not too much. Yet the problem may not be a matter of subjective competence, but of objective contradictions: an economy predicated, more than any other, on the promises of 1990s financialized globalization; a foreign policy pledged to uphold a larger state’s—increasingly nationalist—interests; and a polarized society, in a polity that lacks a convincing ideology of rule. Whether the next five years will be as volatile as the five just gone remains to be seen, but it seems unlikely that Labour’s return to office will do much to relieve the national distemper.