In a famous preface to Sérgio Buarque de Holanda’s classic Raízes do Brasil (1936), Antonio Candido reminded readers in 1967 that the book concludes on a note of doubt with regard to ‘the conditions for democratic life in Brazil’. Buarque acknowledged that in the cities, the old aristocracies were being replaced by cadres coming from below, tempered by the difficulties of work and capable of establishing an egalitarian political order. At the same time, he noted the persistence of older personalist and oligarchic forms. Which of these impulses would prevail remained uncertain.footnote1 The Brazilian elections of October 2022 were a dramatic actualization of this question. The largest country in Latin America—some 215 million inhabitants, an economy ranked thirteenth in the world—commemorated the bicentenary of its independence with a new lease of life for violent forms of sociability. Moving in the opposite direction, a species of democratic concertación, or coalition—though far less formalized than its counterparts in Chile—swept the former metalworker Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva into the Presidency for the third time, by 51 to 49 per cent of valid votes in the second round on 30 October 2022, on a turnout of 79 per cent. A sigh of relief with a samba beat could be heard around the world.

Yet nearly half the electorate—led by military officers and rich businessmen from the agro-industrial, service and construction sectors, followed by an enraged middle class and low-income workers swayed by the theology of prosperity—opted for the autocratic politics of Jair Messias Bolsonaro, who got 58,206,354 votes to Lula’s 60,345,999. The 67-year-old former paratrooper became the first incumbent president to fail to be re-elected since 1988. Nevertheless, the military-religious-agribusiness juggernaut succeeded in returning the largest bloc in Congress, putting the right in a strong position to obstruct any attempt at structural change. Supporters of Bolsonaro won the gubernatorial elections in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais, the three wealthiest states in the country.

After his victory, Lula delivered a carefully written speech in which he promised that ‘the wheels of our economy will start turning again, with job creation, rising wages and a renegotiation of debts for those families who have been losing purchasing power.’ Discontented Bolsonaro supporters nevertheless blocked motorways and camped outside barracks to protest against the result, while the defeated President decamped to Florida. Bolsonaro’s vice-presidential running mate was a retired general, Walter Braga Netto; however, the military appeared to accept the election outcome. In an interview with O Globo another general, Hamilton Mourão, who had been Bolsonaro’s vice-president from 2019 to 2022 and had just been elected as senator for Rio Grande do Sul, turned the page on the issue.footnote2

The politics of what I have elsewhere called an ‘autocracy listing towards fascism’ came one step short of inaugurating a new midnight in Lusophone America.footnote3 This contribution, written as these events were unfolding, attempts to make some sense of the tangled mass of interests, ideas and tactics. Going back and forth across the data, the first section looks at the central role of the poor in the democratic coalition; the second sketches the configuration of the bolsonarista bloc; the third and final section returns to the winning alliance, looking at the class imperatives that dominate it and trying to anticipate the challenges it will face. Quickfire assessments of events that are still underway may, of course, prove partial or exaggerated; what follows is an attempt to assist the process of thinking through contradictions whose ultimate resolution is still a long way off.

1. the centrality of hunger

Two rival alliances coalesced to fight the battle of October. According to the opinion polls, the poor had made up their minds as early as April 2021, when Lula, his ‘Lava Jato’ conviction annulled by the Supreme Court, promised that if he won there would be ‘beer in the glass and meat on the table.’footnote4 In a country that is the world’s largest producer of animal protein, domestic consumption of red meat had fallen to its lowest level since 1996. One opinion poll after another showed around 50 per cent of respondents confirming their intention to put Lula back in the Alvorada Palace, the official residence of the Brazilian president. With a substantial advantage in the polls, Lula went about building an ad hoc coalition that grew ever broader over time. He supported a combative left-wing candidate, albeit sponsored by the tepid Brazilian Socialist Party (psb), for the governorship of Rio de Janeiro. At the same time, he backed a centre-right heavyweight, a populist with links to the dominant local football club, for the governorship of Minas Gerais. Having chosen Geraldo Alckmin as his running mate at the end of 2021—a former governor of São Paulo, current member of the psb and long-time pillar of the centrist Social Democratic Party of Brazil (psdb)—Lula wove around himself a vast patchwork of groups of every kind.

However, the layer of the ruling class that acts as the central nervous system of the Brazilian bourgeoisie—and whose interests (in banking, manufacturing, heavy industry, culture) are most directly related to the nucleus of global capitalism, especially through financial intermediationfootnote5—was reluctant until the very last to join Lula’s cross-section of supporters. There were a few exceptions, such as Gustavo Ioschpe, scion of an automotive-component manufacturer, who said as far back as July that he would vote for Lula. But the organized bulk of this class fraction remained aloof, notwithstanding Alckmin’s best efforts. They pressed Lula for explicit, detailed and concrete concessions in his economic policy—which were not forthcoming. This may be the ultimate reason why the race went to a second-round run-off. Lula won 48.43 per cent of the vote on 2 October, falling just a fraction short of the 50 per cent needed to win on the first round; another 1.6 per cent would have secured an immediate victory for the Lula–Alckmin ticket.

In the second round, when push came to shove—and for reasons that have to do with politics, not economics—bankers found themselves momentarily aligned with trade unionists and the movements of landless and homeless workers; the most advanced sections of industry united briefly with women, blacks, indigenous peoples and lgbtqia+; the media conglomerates made common cause, for an instant, with university students. The unity of this concertación lasted as long as an ice cube (as in Joaquín Sabina’s song): just long enough to evict Bolsonaro and safeguard the institutions of representative democracy—the grounds on which the modern bourgeoisie was willing, however unintuitive it may have been, to press button 13, Lula’s candidate number, in the polling booth on 30 October.footnote6 The honeymoon period, if there was one, lasted no more than ten days, at the end of which the partners resumed their public contest over the direction of the economy, as discussed below.

Understanding this singular aspect of concertaciónismo in Brazil helps us to disentangle the discontinuous and startling rhythms of the symphony that we are trying to comprehend. With poor voters having made up their minds at the start of the campaign, while wealthier ones only did so at the final moment, Lula spent this entire stretch of time semielected, but in actuality non-elected, until the more advanced sections of big business harkened to concerns for representative democracy itself. In contrast to Lula’s arc, Bolsonaro’s bloc climbed slowly and steadily, for it knew what strategy to deploy right from the start. From 22 per cent in December 2021, Bolsonaro inched up point by point to 45 per cent in October 2022.footnote7 Backed by a parallel Brazil, operating on social media, the President silently reassembled an important section of the electoral support that he had amassed in 2018. What he didn’t manage to recover was precisely the sector that joined Lula at the final hour, tipping the balance in his favour.

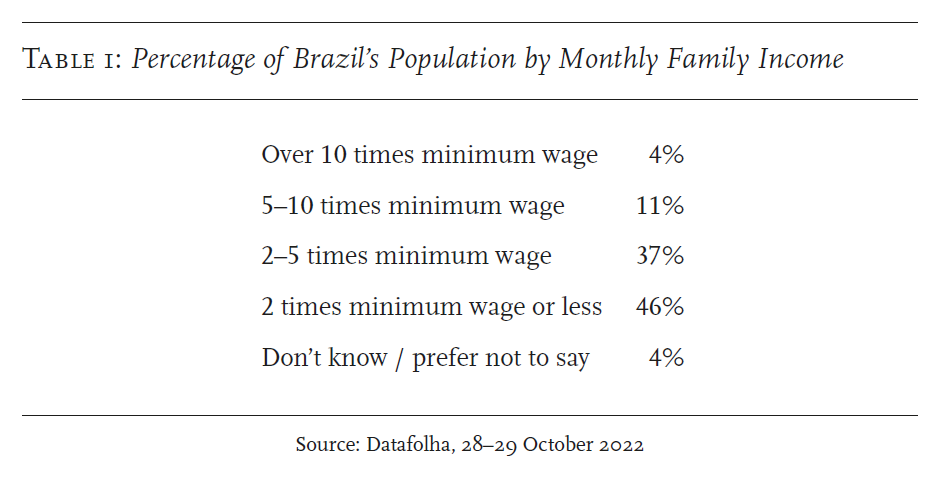

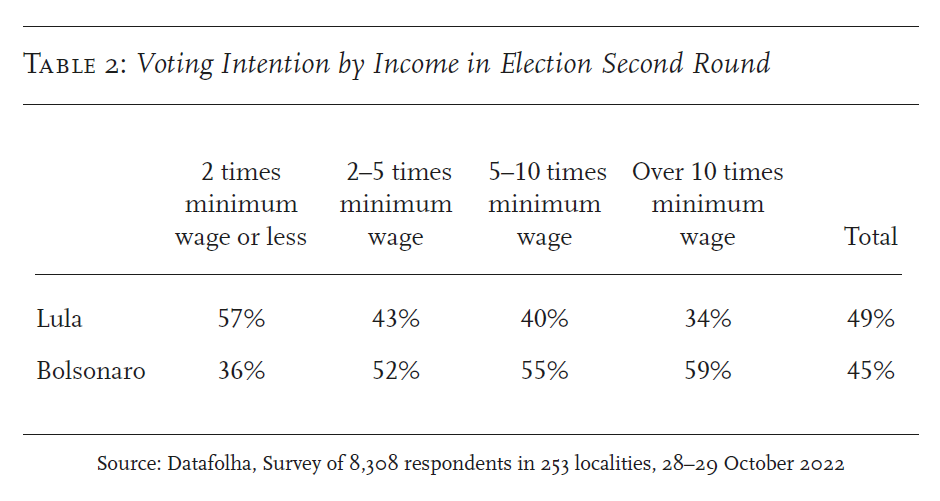

This non-linear tale culminated in a confrontation between two top-down coalitions, comparable to that which took place in the United States in 2020, with the ruling and intermediate sections of society dividing into two camps.footnote8 The poor who, unlike in the us, make up nearly half the Brazilian electorate (Table 1), overwhelmingly inclined to one side, while the lower-income and wealthier layers leant to the other side (Table 2). On the eve of the second round, Lula had a lead of 21 per cent over Bolsonaro among voters whose monthly family income was less than two minimum wages, this being the lowest of the four bands used to stratify polling respondents.footnote9

Polling company Datafolha categorized almost two-thirds of poor voters as ‘vulnerable’, that is, on an income both low and unstable.footnote10 This probably meant Brazil’s sub-proletarians—seasonal agricultural labourers, street vendors, informal security guards, the off-the-books employees of small manufacturers, undocumented domestic workers, and so on—who find themselves ‘deprived of the minimal prerequisites for participating in class struggle’ since they cannot unionize or go on strike.footnote11 Lulismo had emerged as a political phenomenon with the electoral realignment of 2006, which saw the poor and the elderly turn out in their millions for the former metalworker.footnote12 In 2022, it affirmed its sub-proletarian aspect, winning out above all among women and Northeasterners. Lula won in 97 per cent of the thousand poorest towns and cities in Brazil, of which 80 per cent are in the Northeast. This time, he also won in the city of São Paulo, possibly with the help of the remaining third of poor voters, designated by Datafolha as ‘resilient’, denoting a low but stable income, linked to the formal sector of the labour market.

To understand why the poor decided to vote for Lula so early on, we need to take a couple of steps back. In general, the lowest-income Brazilians consistently disapproved of the Bolsonaro government. But with the establishment of the Emergency Aid programme (ae)—pushed through Congress on the initiative of Lula’s Workers’ Party (pt) in April 2020, in response to the pandemic—the President’s ratings, surprisingly, began to rise. The population credited Bolsonaro with the broad scale of the programme, which had some 67 million beneficiaries, as well as its generous payments: around 600 reals a month ($115), three times as much as the Bolsa Família programme established by Lula in 2004.footnote13 As a result, the income of the poorest 10 per cent of Brazilians increased by 15 per cent above inflation. In regions where the cost of living was low, ae benefits could stretch to buying a shack.footnote14 More than 7 million people were lifted out of poverty and, according to the World Bank, extreme poverty in Brazil fell to 1.95 per cent, its lowest ever.

While Bolsonaro lost some middle-class backing during the pandemic by attacking social distancing, opposing masks, advocating chloroquine, joking about the mortality rate and questioning vaccines, he picked up support among the poorer strata. Had he chosen to stick with the fight against poverty, he might have threatened the 2006 electoral realignment represented by lulismo, which combined gradual reform with institutional conservatism. But that was not to be. In early 2021, with an average of a thousand people dying each day, Bolsonaro’s Minister of the Economy Paulo Guedes cut monthly ae payments from 600 reals to 170–370 reals, or $30–$70, while also restricting eligibility. For the excluded, this spelled disaster. By March 2021 the unemployment rate among the poor had surged to 36 per cent; by the end of that year, the income of the poorest 5 per cent was barely half what it had been in 2020. With contagion rates surging, Bolsonaro turned his back on those most in need, who would not forgive his refusal to help them.

Naturally, as the 2022 election approached, the social question returned to the top of the President’s agenda. Bolsonaro’s support among the poorest—those whose monthly family income equalled a single minimum wage—had dropped back to 14 per cent by December 2021, according to Ipec polling, after reaching 35 per cent in September 2020. With the numbers suffering from hunger soaring to 33 million by April 2022,footnote15 the President finally decided to turn the tap back on, pumping around 200 billion reals into the economy. Of course, this was done with both eyes firmly fixed on the forthcoming election. It would take several pages to enumerate all the measures put in place with the aim of attracting low-income voters; a few instances will have to suffice. In January 2022 the Bolsonaro government launched the Aid for Brazil (ab) programme, paying out 400 reals per month, twice as high as the Bolsa Família, which it replaced, and available to some 21 million families, compared to the 14.5 million who received the bf. In August 2022, the level of ab payments was increased again, now reaching the magic figure of 600 reals in place during the pandemic. At the same time, fuel benefits were doubled to 112 reals a month, to help poor families who had been driven back to cooking with firewood. Since these were paid in bimonthly instalments, welfare recipients received over 800 reals ($150) in September. In early October, another half million families were made eligible and the government announced a programme of debt relief, allowing ab beneficiaries to take out additional loans and have the value discounted against their monthly benefit payments, freeing up another 1.8 billion reals ($340 million) for 700,000 people. Finally, the paratrooper-turned-Robin Hood promised an additional thirteenth-month payment to women enlisted in the ab programme.

These benefits allowed Bolsonaro to win a few points in municipalities with high rates of dependence on ab, improving his showing in the north of Minas Gerais, in the Northeastern sertão, in Pará state and in the smaller cities on the western edge of the Central region. The ab helped him to reduce the gap with Lula from 5 points in the first round to 2 points in the second. Still, only 34 per cent of those who received these payments, or who cohabited with someone who did, declared an intention to vote for Bolsonaro, with 61 per cent backing Lula. For comparative purposes: in 2006, voting intentions for Lula jumped from 39 to 62 per cent when the respondent was in receipt of a federal assistance programme.footnote16 Why the difference?

The political scientist Felipe Nunes has suggested that Bolsonaro’s measures were perceived by voters as nakedly electoral in character; there was scepticism about whether the 600 reals would continue.footnote17 It’s also possible that ab payments were being used to pay off household debts—79 per cent of recipients were in debt as of September 2022—with double-digit inflation eroding what was left. The revelation that the Ministry of the Economy was looking at ways of de-indexing the minimum wage and welfare benefits from the inflation rate may have been the final straw.

However, bolsonarismo not only made use of the carrot of concessions; it also brought out the stick of generalized political intimidation, physical assault and economic coercion by bosses, all of which proliferated as the election dates grew closer. Ilza Ramos Rodrigues, a middle-aged day labourer in Itapeva, in the state of São Paulo, told a reporter that the donation of basic goods she usually received from a pro-Bolsonaro businessman had been suspended due to her pro-Lula sympathies, and she was often faced with ‘an empty cupboard’. She nonetheless remained firm in her vote. Lula has ‘always been on our side’ and ‘with the poor’, she told the Folha de S. Paulo in mid-September. These layers took to calling 77-year-old Lula painho, ‘little father’, in the style of Bahia. Much like Getúlio Vargas, who was referred to as the pai dos pobres, ‘father of the poor’, when he was re-elected in 1950 at the age of 68, the painho assembled a mixed concertación; but above all, he owes his return to office to the weakest.

2. the bolsonaro bloc

Despite the growth of lulismo among the lowest-income voters, Bolsonaro had a lead of 9 per cent among those with a family income of 2–5 times the minimum wage, who constitute around 40 per cent of the electorate (Tables 1 and 2, above). It was this layer, which includes the majority of ‘formal’ workers, that made the extreme right competitive in 2022. The key question is: why? First, Bolsonaro was able to create something of a feel-good factor through a plethora of fiscal measures directly affecting this stratum—reductions in fuel tax, fuel vouchers for taxi drivers and truckers, expedited payment of end-of-year bonuses for pensioners, liberalization of national-insurance funds to allow down-payments on mortgages. Brazil’s gdp grew by 2.5 per cent in the first quarter of 2022 and the value of the real rose by 1.3 per cent in the third quarter. Unemployment fell from 11 to 8.7 per cent between the end of 2021 and September 2022, at which point 53 per cent of Brazilians thought the economic situation was likely to improve in the coming months, the most optimistic outlook since the start of Bolsonaro’s tenure.

These measures helped to re-activate the long-standing right-wing leanings of some sections of Brazilian society; but other material and ideological factors were almost certainly crucial in allowing Bolsonaro to nearly equal his 2018 support among voters in the 2–5 times minimum wage bracket.footnote18 In the Brazilian context, many of these workers can be considered part of the lower-middle class. They seem to have been attracted by a novel conjunction between forms of production and corresponding visions of the world. The commodities super-cycle, picking up at the start of 2021 and still strong in the run-up to the election, offered fresh opportunities for this. Overseas demand for raw materials and the devaluation of the real drove an expansion in agricultural production of 24 per cent in 2020, despite the pandemic. Agriculture as a whole contributed 27 per cent of gdp, while the once-weighty industrial sector was reduced to 11 per cent. Farm production expanded by another 8 per cent in 2021; Brazil’s grain yield the following year was its highest ever. ‘Practically all the orange juice consumed around the world comes from the trees of São Paulo state’, the Financial Times reported in July 2021; according to the head of Embrapa, a government agricultural research institute, in some places ‘sustainable tropical agriculture’ made it possible to reap three harvests a year.footnote19

A novel ‘confederacy’

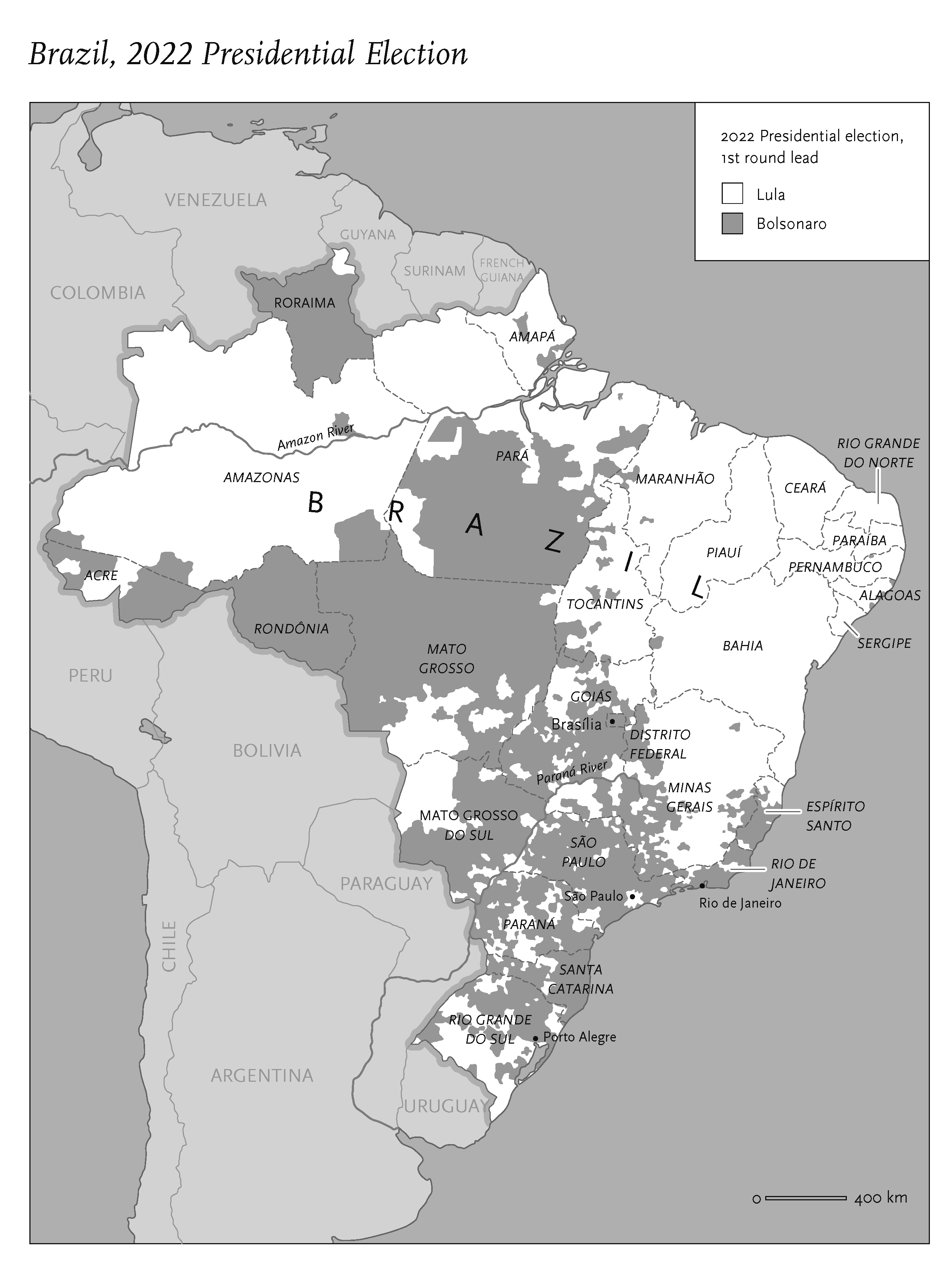

As the economist Bráulio Borges has pointed out, the heartlands of bolsonarismo map closely onto these vast plantations, whose profits rose in real terms by 30 per cent under Bolsonaro.footnote20 This is an immense Texas-style enclave, running from the north of Rio Grande do Sul through Santa Catarina—where pro-Bolsonaro protesters were filmed giving Nazi salutes after the election outcome—and the Centre, right up to the borders of the Northeast (see Map). These regions enjoy jobs, dollars and liveable cities, where one can indulge in sertaneja country music, recreational shooting and right-wing fervour. This helps to explain why the agrarian fraction of the ruling class, however ‘modern’, diverged from the main trunk to propound a programme that the economist José Luis Oreiro has called fazendão, or ‘plantationism’.footnote21 As one would imagine, this means more guns, lower taxes on agribusiness and a sustained rollback of workers’ rights, environmental protection and the demarcation of indigenous territories.

At stake here is a novel political alignment which we might dub a bolsonarista Confederacy. The allusion to the us Civil War must be taken cum grano salis: there is no slave system in 21st-century Brazil, nor any looming threat of a civil war for secession. But the term speaks to the consolidation of a coalition with both a territorial, an economic and a social basis, whose outrage takes form in a kind of political-ideological secessionist sentiment: we don’t want to be part of the lulista Brazil, with its typical social (poor, black) and territorial (Northeastern) base. This confederate-export model, legitimating anti-Northeastern xenophobia and a degree of separatism, succeeded in pulling in some sections of the working class. It saw itself in bolsonarismo, whose motto might be: society should not be integrated, just hierarchized.

As Bolsonaro relaxed controls on the destruction of the Amazon rainforest—under his administration, deforestation increased by 60 per cent—and allowed the invasion of tribal reserves, loggers and miners in the North, many of them operating illegally, gave enthusiastic backing to the Confederates. The far right triumphed in the 265 municipalities of the nine Amazonian states. In the town of Novo Progresso, Pará state, where in 2019 estate owners promoted a ‘Bonfire Day’ initiative of coordinated fire-setting that made world headlines, Bolsonaro could count on 80 per cent of votes. In the second round he got a majority in the states of Acre, Rondônia and Roraima, drawing practically level across the broader Northern region.

In the big cities, the Confederacy had the support of construction and service-sector chiefs, symbolized by Luciano Hang, the head of a department-store chain. Nouveau-riche bosses of language schools, restaurants, car dealerships, gyms, sports shops and construction firms were actively engaged with the export-agribusiness model, to which they could adhere as subsidiary parts. Behind them came a vocal section of Brazil’s 20 million small-business owners, some of whom would count as members of the lower-middle class. Fully 77 per cent of those ‘business-owners’ planned to vote for Bolsonaro in the final round. One of them, the 31-year-old Thaís do Carmo from Betim, Minas Gerais, explained to Le Monde that, ‘as a businesswoman’, she naturally ‘detests the left’.footnote22

In August 2022 Hang, the department-store boss, who usually appears with a shaved head and lime-green suit, paired with a garish yellow tie, responded to the ‘open letter’ by business leaders in support of democracy (discussed below), by saying that ‘millions of businesspeople’ would sign ‘the opposite manifesto’.footnote23 He may well have been right. The only municipality in Pernambuco state to give Bolsonaro more votes than Lula was Santa Cruz do Capibaribe, a clothes-manufacturing hub with many small businesses where average household income was 2.5–4 times the minimum wage. According to the anthropologist Maurício de Almeida Prado, the small-state discourse had many adherents among these ‘strivers’. The political scientist Antonio Lavareda argued that this sector made a causal link between ‘the corruption underlined by the Lava Jato affair and the impoverishment of society.’footnote24

The military party

Professionals of ‘the bullet and the Bible’ played a significant role in the bolsonarista bricolage. Generals and religious entrepreneurs brought a constitutional and moral dimension to the economic platform of the Confederacy, contributing to its salience in the media. Connecting the world outlook of the interior to the problems of city life, they called for less liberalism in politics, less state in the economy, more family—in response to the atomizing precarity of late capitalism—and, to meet the acute challenge of public safety, more repression.

The issue of public safety has enormous salience in a nation where there were over 200,000 homicides between 2008 and 2011, nearly triple the number (76,000) killed during the first three years of the us occupation of Iraq. With over 700,000 people in jail, Brazil has the third-largest prison population in the world, after the us and Russia; its overcrowded cells were described as ‘medieval dungeons’ by one of Dilma Rousseff’s ministers. Large numbers are employed in the security industry: 380,000 in the army, navy and air force, around 400,000 military police, another 130,000 civil and federal police officers, plus a million or so private security guards. This is why the role of the Armed Forces and the state-level Military Police is so relevant: reinforcing the association between the ‘Order and Progress’ message of the green and yellow national flag and the capillary role of the lower ranks of those employed in armed services.

Pro-gun, pro-prison and hostile to human-rights universalism, the bolsonarista wave proved ‘powerfully seductive’, not only to the Armed Forces and Military Police but also to the civil and federal police forces, according to the journalist Fabio Victor’s important book, Poder camuflado. Another study shows that in 2021, roughly a third of the Military Police had interacted with radical bolsonaristas online. Marcelo Pimentel, a reserve colonel who has made a study of what is called the ‘Military Party’ notes that fourteen of the seventeen generals who made up the High Command of the Armed Forces in 2016 held leading posts in Bolsonaro’s government in 2021.footnote25

The return of the generals to the decision-making arena, from which they had been banished after the dismantling of the 1964–85 military dictatorship, belongs to a story that stretches back to the proclamation of the Republic in 1889. In the recent period, it may be helpful to distinguish four key stages. In the first phase, under the presidencies of Fernando Henrique Cardoso (1995–2002) and Lula (2003–10), the military regime still constituted a cult for an undetermined but significant number of officers in the barracks. Such views were expressed publicly only by a few figures in the reserves, however, passing under the radar of most scholars and politicians, leading to the false impression that younger officers were immune to the attractions of authoritarianism. The second phase began in 2011 when Dilma Rousseff, Lula’s successor, established the National Truth Commission (cnv), whose task was to investigate the deaths and disappearances of oppositionists under the dictatorship. The cnv’s report, delivered in December 2014, found that around a hundred living military figures had been violators of human rights. As Victor notes, this provoked an outcry from the officer corps and ‘political interventions by serving generals’. The third phase saw the impeachment of Dilma in 2016, while her Vice-President Michel Temer gave the military ‘a degree of power not seen for 21 years.’footnote26

Finally, this gradual return resulted in a presidential candidate with a base in the Armed Forces. Bolsonaro, a 1977 graduate of the Military Academy of Agulhas Negras, equivalent to West Point, launched his presidential run at a cadets’ graduation ceremony at the school. Despite having nearly been expelled from the Army for indiscipline in 1988, he was ‘amnestied’ by his former colleagues. After the debacle of the 2016–18 Temer government, which rapidly descended into a morass of corruption, members of the Armed Forces flocked to the candidacy of this previously unremarkable congressman, increasingly spoken of as a ‘legend’ by his admirers.footnote27 At a key moment in the pre-campaign season of 2018, the head of the Armed Forces issued a public message to the Federal Supreme Court, which was due the next day to deliver its judgement on a writ of habeas corpus that might have opened the way for Lula, then under arrest on Lava Jato charges in Curitiba, to contest the race. According to the message, the Army would not stand for ‘impunity’. The writ was denied, and Bolsonaro became the 38th President of the Republic.

According to Vice-President Mourão, the Bolsonaro administration was not a military regime, but one made up of ex-military men. Yet of the 5,000 executive posts occupied by uniformed officers—including, as we have seen, top-level positions—according to Victor’s calculations, 60 per cent were currently serving. In addition to a near-doubling of members of the Armed Forces absorbed within the government apparatus, military and police bodies received numerous material benefits. The ‘Military Party’ reciprocated, demonstrating its support for the leader’s autocratic designs, despite continual disclaimers. To take one of several examples: General Paulo Sérgio Nogueira de Oliveira, a former commander of the Armed Forces, set aside his ‘moderate’ image as soon as he was appointed Minister of Defence in March 2022 and promptly revealed himself to be ‘an ardent militant’.footnote28 Nogueira de Oliveira was accompanying Bolsonaro in July 2022 when the President made his most forthright threats of a coup, attacked the integrity of the electronic voting booths and made clear, in front of an audience of forty foreign ambassadors that, in the event of his defeat, he would support an institutional rupture like that attempted by Trump at the us Capitol. In response, a spokesperson for Biden’s State Department certified that Brazil’s electoral system was not only ‘capable and time-tested’, but a model for other nations.

Support with strings

Three weeks later, on 11 August 2022, it was the turn of the financial-industrial bourgeoisie to unfurl the banner of legality, in the open letter mentioned above that earned Hang’s contempt. ‘The attempt to destabilize democracy and public confidence in the impartiality of the electoral system’ was not successful in the us, and ‘will not be here either’, the signatories affirmed.footnote29 The date marked a division within the Brazilian ruling class. Those in finance and big business professed their faith in ‘democracy’ (though not in Lula). Those who did not sign the letter, led by modern agribusiness, sided with the Confederates. Of course, there were those in agriculture and the service sector who supported the democratic system, and those in finance and industry who backed Bolsonaro. But the general line of division between the two fractions had been drawn. The same applied to the traditional middle class, which split in two: the larger section—55 per cent, as in Table 2—did not follow the lead of big business and finance, with which it had kept in step since the return of electoral democracy in 1985.

The support of the financial-industrial bourgeoisie came with strings attached. Knowing perfectly well that no candidate stood a chance of beating Bolsonaro unless they were rooted in the broad mass of the population, the business bloc that had moved to forestall a coup d’état on 11 August decided to put wind in the sails of Simone Tebet, a centrist mdb senator from Mato Grosso do Sul, hoping to gain leverage in their negotiation with Lula. Tebet presented herself as a moderate alternative to the two main coalitions, ultimately receiving 4 per cent of the vote in the first round—in which, let us recall, Lula missed winning outright by just 1.8 per cent. Ciro Gomes, a centre-left candidate, received 3 per cent running for the Democratic Labour Party (pdt). Once the first round had made clear that every vote would count, Gomes gave a perfunctory endorsement to the democratic coalition and retired from the stage. Tebet, on the contrary, called for a further enlargement of the concertación and took on a combative role in the new alliance. Behind the scenes, another tug-of-war was under way. The advanced capitalists wanted a ‘dramatic gesture’ from Lula, committing himself to fiscal responsibility, even though the manifesto lodged with the Superior Electoral Tribunal pledged to ‘revoke the public spending ceiling’.

On 6 October, with this still unresolved, four prominent economic thinkers from the psdb—Pedro Malan, Edmar Bacha, Armínio Fraga and Persio Arida—spoke, as it were, for modern financial-industrial capital, declaring that they would vote for Lula, with ‘the expectation’ that there would be ‘responsible management of the economy’. The Economist, which might be seen as the thermometer of foreign capital, had done the same 48 hours earlier. The ‘serious’ broadsheet press, openly antagonistic to Bolsonaro, broadcast these facts far and wide and, for three weeks, placed democracy above distrust of lulismo.footnote30 Fifteen days after the declaration by the psdb quartet, Lula briefly remarked, in a speech at the theatre of the Catholic University of São Paulo, that ‘this won’t be a Workers’ Party government’. In doing so, according to the journalist Cristiano Romero, he sent a message both ‘to the more left-wing currents in his party and, of course, to the markets.’ There would be no space in the government for Workers’ Party members ‘who raised the slightest doubt about the course of economic policy’ under a third Lula term.footnote31 The presence at the event of Henrique Meirelles, architect of the public-spending ceiling, former global president of BankBoston and president of the Central Bank under Lula, as well as Persio Arida, another former president of the Central Bank from the Cardoso years and mastermind of the 1990s anti-inflationary currency reform, the Plano Real, underscored the message.

Conservatives and Christians

The ‘Military Party’, meanwhile, seems to have understood that trying to overturn the established procedures of the election without the support of advanced financial-industrial capital or the us would result in its isolation and inability to govern. The autocratic programme would have to be advanced within the framework of the democratic institutions, at least for now. As Mourão said in conceding defeat: ‘We agreed to take part in a game in which the other player [Lula] should not have been taking part. But if we agreed, there is nothing more to complain about.’ Asked about the pro-Bolsonaro protests, he replied: ‘These should have taken place when the player who shouldn’t have been in the game was allowed to compete. They should have started this ruckus in the streets then, but they didn’t.’footnote32

In compensation, the 2022 elections saw a significant increase in elected representatives linked to the security services, with 48 federal deputies elected and 39 at state level—a 27 per cent rise.footnote33 The Confederate political machine, with its security components and economic leadership, has the conditions it needs to keep functioning, even if the ‘legendary’ Bolsonaro fades after 2023. Indeed, some think the charisma of the ‘legend’ has purely parochial roots. According to the journalist Bruno Paes Manso, Bolsonaro and his sons are ideological representatives of a militia culture that grew up in Rio de Janeiro and ‘went all the way to the presidency of Brazil’.footnote34 The militias in question were units set up by serving and former police officers in Rio from the 1990s, which took on the role of providing ‘security’ in areas supposedly overrun by predatory drug dealers. The militias collected protection money and forced residents to pay them for services—illegal cable tv connections, taxes on transport cooperatives and a high percentage charge on car purchases and rentals. One study estimates that in the past thirty years, Rio militias have taken over half the territory once controlled by organized crime, with over 4 million inhabitants. An analysis of the first-round vote shows that Bolsonaro swept neighbourhoods with a high militia presence.footnote35

Rio, too, is the state where Pentecostal groups have the greatest influence. Evangelical preachers staged hunger strikes in protest at the prospect of Lula winning the first round, and religious pressure may have been the main influence there. In Minas Gerais, where no militia groups are known to operate, the advance of bolsonarismo in the second round was attributed to Evangelicals. With the backing of 30 per cent of the population and a recently elected slate of 92 representatives, prominent Evangelical churches launched an unprecedented national mobilization in favour of Bolsonaro. His 2018 vote had already been linked to Evangelism, but the 2022 election cycle witnessed a Biblical-conservative upsurge unlike anything ever seen before. Himself a Catholic, Bolsonaro invested systematically in building relationships with Evangelical leaders. From 2011 onwards, he began to incorporate ‘themes related to sexual morality’ into his legislative activity and famously had himself baptized in the River Jordan. Once in office, he had the slogan ‘God above all’ plastered everywhere, applied religious concepts to decisions of state, appointed Evangelical figures to ministerial and Supreme Court roles, opposed restrictions on religious groups during the pandemic and forgave a debt of 1.4 billion reals owed to the state by churches.footnote36

In return, religious leaders—including the billionaire Edir Macedo, founder of the mega-church Igreja Universal do Reino de Deus (iurd)—gave the bolsonarista project their enthusiastic backing. Macedo’s tv channel Rede Record, Brazil’s second-largest, joined other media, including Jovem Pan, an outfit modelled on Fox News, in counterbalancing the critical coverage of Bolsonaro by Globo, the country’s biggest and most influential tv network. An iurd missive in September 2022 reiterated Macedo’s support for the President, since ‘Evangelical thinking’ could not accept ‘the constant attack on the traditional family structure, made up of father, mother and children.’footnote37

At the start of the election campaign, religious entrepreneurs flooded the country with an army of fervent proselytizers, giving voice to what political scientist Marina Basso Lacerda has called a ‘Brazilian paleo-conservatism’.footnote38 Imported from the us, this preaches that a good society is not attained through public policy or redistributive measures, but through ‘the strengthening of the family as a font of provision for its members’. As Bolsonaro told the United Nations, the family was the mother-cell from which a healthy society would emerge. A ‘conservative and Christian’ Brazil would need to defend its internal moral order against those intent on undermining it. While Bolsonaro avoided explicit opposition to the secular state, that was effectively at issue, given that a Christian country leaves those who are not Christian in a position of inferiority. A rhetorical inversion of reality takes place, transforming the aggressor into a victim.footnote39 The message is that the enemies of the family aim to destroy this pillar of a good society and so must be suppressed—when in reality, the ones who want to suppress the other and refuse to allow diversity are the paleoconservatives.

A study conducted in a peripheral area of southern São Paulo in the 2010s traced the slow diffusion of anti-Workers’ Party talking points among working-class Evangelicals, generally those in the 2–5 times minimum-wage bracket—beauty-parlour employees, shop workers, security guards, police officers—that went together with worsening economic problems and accusations of corruption aimed at the pt.footnote40 It may be this cocktail of molecular anti-pt sentiment and paleoconservatism that explains the fanatical character of 2022’s political polarization. In language that recalled that of the American far-right agitators of the 1930s studied by Löwenthal and Guterman, political opponents were no longer conceived as human obstacles to the achievement of particular goals, but as a body external to society, the incarnation of evil itself.footnote41

Addressing a congregation of the Baptist Church of Filadelfia in Salvador, Bahia, shortly before the second round, a pastor elected to Congress spoke of ‘a civil war against the imminent evil of a possible victory of the left.’ A member of another church reported that the pastor had said that, if Lula was elected and they came to burn down the churches, ‘he’d make sure that whoever had voted for Lula was the first to burn.’ In Belo Horizonte, a pastor with a weekly congregation of five thousand used his pulpit to accuse Lula of supporting abortion and the legalization of drugs, wanting to restrict the media and release those convicted of petty robbery.footnote42 The pressure was such that Lula felt obliged to publish a ‘Letter to Evangelicals’, two weeks before the second round, assuring readers that he would not obstruct the free functioning of places of worship, that he was personally opposed to abortion and committed to ‘strengthening families so that our young people are kept well away from drugs.’ Yet, starting from a dead heat with Lula among Evangelicals in December 2021, the agitation of the pastors gave Bolsonaro a 20-point advantage among them in the run-up to the second round.

3. the grand coalition

In Brazilian politics, characterized by a hyper-trasformismo that would baffle even Gramsci, the most fanatical of positions can be altered with a change in the wind. On 3 November 2022, Edir Macedo preached ‘forgiveness’ of Lula. Realpolitik was even swifter. Negotiations with Congress began immediately. The president of the House of Representatives, Arthur Lira (pp–Alagoas), a Bolsonaro ally who speaks for the Centrão—the largest grouping in Congress, with around 300 representatives, mainly conservative—didn’t even wait for the formal announcement of the results on 30 October to dash in front of the news cameras and say that the will of the people expressed at the polls ‘must never be contested’. Right on cue the president of the Senate, Rodrigo Pacheco (psd–Minas Gerais), also on good terms with Bolsonaro, followed his colleague from the House: ‘We can offer the people a grand coalition of alignment between the institutions in the forthcoming government.’

What Lira and Pacheco wanted in return for this conspicuous about-face—which also served to discourage possible moves towards a coup by pro-Bolsonaro extremists—was Lula’s support in re-electing them to the presidencies of their respective Houses in February 2023. Furthermore, they wanted the continuation of what has become known as the ‘secret budget’, a mechanism in operation since 2019 and made official by Bolsonaro in 2021, in which the leader of the House is given a huge pot of money—some 20 billion reals ($3.8 billion)—to dole out in legislative amendments. Portions of these funds can be spent by the legislators within their own constituencies, without having to detail the works undertaken or provide any accounts. This was a (scandalous) expedient for buying control over members of Congress, as those in receipt of these monies tend to be re-elected; the 2022 election saw the lowest rate of turnover in the House since 1998. The secret budget strengthened the position of the leader of the Chamber, already empowered by a clause in the Constitution stipulating that he, and only he, can decide whether to forward articles of impeachment submitted to him to the plenary of the House. Bolsonaro accepted the secret budget as the price of avoiding his own impeachment and thus became the ‘tchutchuca do Centrão’, according to one of his own supporters—candidly rendered by Associated Press as ‘the “darling” of a pork-barrel fraction of Congress’.footnote43

Since Lula also needs Congress’s support in order to escape impeachment, as well as to pass the social programmes he has promised, he too has made use of hyper-trasformismo, actually supporting the re-election of Lira and Pacheco. But in the process of negotiating with them, he was able to extract some concessions. The story is full of twists and turns. In the aftermath of the election, Lula—like any Brazilian president—had to negotiate with numerous Congressional parties and even independent members until, following the rule of the ‘grand coalition’, he had enough parliamentary support to govern.footnote44 Deputies are elected by proportional representation at state level, so the absolute national-majority support vested in the President is not reflected in the Congress. And thanks to its flexible rules on party formation, Brazil has long had one of the most fragmented party-political landscapes in the world. In 2022, 23 organizations were represented in the 513-member House, meaning that each had only a small bloc of representatives.footnote45 Since the parties of the pt’s pre-election coalition had only 154 House seats, the psd and the mdb—the party that led the parliamentary coup against Rousseff in 2016—were swiftly invited to enter Lula’s third Cabinet. In theory, for individual party loyalties are also fairly relative, they bring with them 83 seats. The conservative Brazil Union party, with a valuable bloc of 59 seats, has also been given Cabinet positions, but even so it is divided about supporting Lula. By these means, Lula’s government has mustered a narrow majority in the House, but at the cost of encompassing the entire ideological spectrum from left to right, excluding only the pro-Bolsonaro parties. In the Senate, the bolsonarista candidate for speaker was defeated by 49 to 32 votes on 1 February.

If these ambiguous groups can be held together—always a costly proposition—a new impeachment can be avoided. But even they were not enough to pass amendments to the Constitution, which requires 308 deputies and is essential for even a minimal legislative programme, since the Brazilian Constitution is extremely detailed, leaving little to chance. Analysts suggested as early as October that Lula would also try to co-opt members of pro-Bolsonaro parties within the Centrão, reeling in individual deputies.footnote46 After Macedo’s swift volte-face, the Republicanos, a party linked to the iurd, declared itself ‘non-fervent’ in opposition. Some in the Progress Party (pp), the principal heir of the dictatorship, were also inclined to join Lula. Even in the Liberal Party (pl), an organization created in 1985 and colonized by Bolsonaro in 2021, around 40 of the group’s 99 members of the House favoured entering a Lula-led government. But party boss Valdemar Costa Neto, acting under pressure from Bolsonaro, took a hardline stance. The mantle of opposition has thus fallen to the pl as a platform from which to destabilize Lula’s government. On the other hand, the psdb, former hegemon of the middle-class vote, now with only 13 representatives, has declared itself independent from both Lula and Bolsonaro; and with it, perhaps, the modern financial-industrial capitalist fractions.

Brazil’s economic situation, combined with global recessionary and inflationary pressures, made it imperative for Lula to achieve some kind of budgetary resolution by the start of 2023. A ‘feel-bad’ factor was just what the forces of the Confederacy were hoping for, to light the bonfire that would burn up his accumulated political capital. Since fiscal breathing-room was ruled out by a 2016 constitutional amendment that imposed a very strict ceiling on public spending, the issue was set to tug at the seams of the Lula government’s cross-class patchwork. Moreover, Lula’s speech on 21 October, in the presence of Meirelles and Arida, had seemed to rule out any redistributive moves. Had he capitulated to those pressures which Rui Falcão, former president of the Workers’ Party, had in mind when he warned of being pushed into ‘adopting a programme that is not our programme’?footnote47 The truth is that Lula was seeking a formula for conciliation, which is what he attempted in his ‘Charter for the Brazil of Tomorrow’, released 48 hours before the vote: ‘It is possible to combine fiscal responsibility, social responsibility and sustainable development’. The financial sector predictably considered the document too generic, with no answers as to where the money would come from to meet so many demands.

However, the need to fulfil the promises made to the poor and provide debt relief to families, raise the minimum wage and fund public-safety measures, the health system, education—in short, the national reconstruction that so many were hoping for—pushed Lula, in a clever move, to negotiate with Lira even before being sworn in. In crude terms, he swapped his implicit support for Lira and Pacheco’s re-election for a waiver of expenditure limits in the first year. Formally, Lula gave control of his transition team to Alckmin and named Arida as one of his economic-policy coordinators, along with three other economists, two of them Workers’ Party members.footnote48 Arida advocated a plan for a ‘waiver’ to allow expenditure of 100 billion reals ($19 billion) above the spending ceiling—well short of what people on the left judged necessary for a reconstruction project modelled on Biden’s address to Congress on 28 April 2021. It was not even enough to guarantee the ‘social minimum’: Lula’s pledge to maintain the Bolsa Família at 600 reals, with an additional 150 reals for each child up to the age of six.

Then Lula unleashed his audacious shot on goal—going into direct negotiations with Congress, that is, Lira and Pacheco, without consulting the team of economists he himself had appointed under Alckmin’s authority. At the same time, the ‘secret budget’ was put before the Supreme Court, which ruled it illegal. This meant that Lira had to accept the intermediate solution which Lula was offering, which will involve further negotiations between the speaker of the House (Lira) and the Executive (Lula) about the allocation of part of what was the ‘secret budget’. For sure, Lira will do everything in his power to keep the control of the money. At the same time, Lula will try to extract legislative concessions from him, in exchange for the amendments he wants. As for the results of this fierce battle, only time will tell. But Lula, with the decisive help of the Supreme Court, has been able to regain some power for the presidency.

The so-called ‘Constitutional Amendment for the Transition’ that Lula extracted from Congress waived the annual spending cap by 50 per cent above Arida’s proposal, increasing the amount to around 150 billion reals, which should guarantee the ‘social minimum’ up to the end of 2023. After hard bargaining, the constitutional amendment was passed on 21 December 2022. Will it be enough? Estimates are that it will suffice for the ‘social minimum’, maintaining the 600 reals of the new Bolsa Família, plus 150 reals per child up to the age of six. In other words, Lula got from Congress enough to benefit his constituency: the poor. A family with two children under six will receive a monthly 900 reals, not so far below the minimum wage of 1,300 reals. But there will remain only 23 billion reals for all the rest.

‘A very bad start’ for the new government, a management consultant told the Financial Times.footnote49 Although the core fraction of the bourgeoisie was impelled to take the side of the poor for the sake of democracy, it may soon find itself displeased at the expense of having done so. There is reason to fear it may become nostalgic for the programme of Paulo Guedes, Bolsonaro’s Minister for the Economy, who insisted—even to the point of risking his boss’s defeat—on the necessity of stripping the budget of its ‘indexes, ties and obligations’, opening the way for pensions and the minimum wage to fall behind inflation. All that said, the real opposition is likely to come from the Senate. With key ex-ministers elected as senators, a brigade of bolsonaristas is trying to create an anti-Lula bunker in the Upper House. And can Lira, the man who covered Bolsonaro’s back in the Chamber, be counted on when hard times come? And with such a broad coalition, will there be enough consensus to sign off on programmes that can convince the population that democracy is worth the trouble?

A riot and its meanings

When much of this essay was already written, the bolsonarista riot of 8 January 2023 vented its fury on the beautiful buildings designed by Oscar Niemeyer in Brasília. Beyond the material, and maybe irrevocable, damage to the core democratic institutions of the nation, what is to be said about the political consequences? According to Ross Douthat, writing in the New York Times, the storm seen in Brasília was only performative, since Lula had already been sworn in the week before, on 1 January, and neither the Executive, Legislature nor Judiciary were working, as it was a Sunday. The crazy extremist multitude, assembled from many parts of the interior, wasn’t seriously trying to disrupt electoral democracy, Douthat argued. They were just putting on a show to evoke the images of the Capitol invasion on 6 January, two years earlier.footnote50

On the timing of the vandalism, Douthat is right. It exploded when, thanks to Lula’s deft handling of Congress, popular expectations for the new government were on the rise. Thanks to that pragmatic wisdom, the hundred days of general goodwill after his moving inauguration were underway. That is why the astonishing violence against the democratic institutions in the Praça dos Três Poderes petered out in emptiness and isolation, besides being energetically repudiated by the overwhelming majority of Brazilians. It may have helped, perhaps, to inflict a mortal wound on bolsonarismo. That will depend on whether the alliance between the government and the Supreme Court proves able to profit from the opportunity.

But there are three aspects on which Douthat’s analysis falls down. The first, curiously, has to do with its success. The incredible will to be like the Trumpists of the crowd assembled on 8 January is peculiar, something that needs to be studied on its own terms. Although the American invention of 2016 had an impact worldwide, the Brazilian social landscape was probably the most deeply affected by the Trump experience. The impulse to imitate the us is constitutive of Brazilian republican history. When the monarchy was abolished in 1889, giving birth to the republic, the first flag proposed for the new Brazilian regime had stars and stripes, in yellow and green. After a conciliation period, it ended up with stars in a globe, without stripes, resulting in a design rather similar to the old imperial ensign. It is possible that bolsonarismo has effected a new leap in this trajectory, approximating Brazilian to American politics more than ever.

The second aspect refers to the symbolic consequences of the episode. It is dangerous to overstress the weight of symbolism in politics; after all, what is done is more important than what is said, as Marx taught. But representations, words and symbols have a special place in politics. That day in January was impressive enough not to be forgotten, even in a culture that has a tendency to forget everything. It will always be a reminder that bolsonarismo, at the end of the day, is not absorbable by democracy, even if it aims to act in a crypto-authoritarian fashion.

The third point concerns the political responsibility of the military, police, officials, Evangelical pastors and entrepreneurs for the events of 8 January. Their involvement shows that the imitative performance noted by Douthat was also a warning from one part of the Confederate bloc to the concertación. From the Governor of Brasília, whose police welcomed the ‘protesters’, to the military who prevented the imprisonment of some of those seeking refuge at the ‘camp site’ near the Army headquarters, not to speak of the entrepreneurs who financed the destruction, the message was: we don’t accept conciliation and haven’t laid down our guns. The investigations by the Supreme Court and Federal Police now underway have the means to outlaw many people, including the former President.footnote51 If this is to happen, it will depend on the conviction, degree of unity and, last but not least, popular support for the grand coalition in the months ahead.

The dilemma brings us back to the predictions of Buarque and Candido. For both of them, democracy could only prevail in Brazil if it served to hasten ‘the emergence of the oppressed strata of the population, who are the only ones with the ability to revitalize society and give a new sense to political life.’footnote52 In donning the presidential sash on the first day of January this year, Lula has also taken on responsibility for opening up new perspectives for those at the bottom, under the threat of an autocratic resurgence that would wipe the fair Southern Cross from the map of the stars and from the tropical flag.