In the weeks following the 2022 us midterms, the mood in the intellectual penumbra of the Democratic Party swung wildly from impassioned handwringing to euphoric self-congratulation. Dire warnings of a ‘red wave’ delivering large congressional majorities to the Republicans gave way to jubilation at the salvation of democracy. In reality the results were decidedly mixed. The Republicans took the House with a narrow majority, while Democrats retained their slim hold on the Senate. The Republicans swept Florida and flipped a handful of districts in New York. Reproductive rights had a fairly good night, but Democrats continued to fare very poorly with non-college-educated whites––according to one poll, Republicans won over 70 per cent of white men without a college degree.footnote1

Various explanations have been offered for the weaker than expected Republican performance, in the context of a deeply unpopular President and high inflation. Among the leading hypotheses is the poor ‘candidate quality’ of many Trump endorsees; the Supreme Court’s overturning of the constitutional guarantee of the right to abortion with the Dobbs v Jackson ruling this summer; and—at 27 per cent—the relatively high turnout among young voters. All these points have some plausibility, but they miss the larger issue. American politics has undergone a tectonic shift over the past twenty years, linked to deep structural transformations in the regime of accumulation. These transformations have not been adequately sketched and theorized as yet; the unforeseen midterm results are a good occasion to begin to do so.

What we offer here is not a finished argument but a set of seven telegraphic theses, flanked by empirical evidence, intended to provoke further discussion of these critical questions. To that end, we begin with a brief sketch of the current conjuncture and a clarification of terms.

1

For most of the twentieth century, us political parties represented different coalitions of capitalists, who appealed to working-class voters on the basis that they would promote economic development, expand job opportunities and generate revenues to invest in public goods. This was the ‘material basis of consent’ that determined party success at the polls: a local version of the politics that shaped most capitalist democracies during the long post-war boom. In the us, this produced significant electoral swings, and big congressional majorities for the winning side: Eisenhower in 1956, Johnson in 1964, Nixon in 1972. That political landscape has now disappeared. Beginning in the 1990s, and definitively since 2000, Republican and Democrat rule alternates on the narrowest of margins. Winning an election no longer involves appealing to a vast shifting centre but hinges on turnout and mobilization of a deeply but closely divided electorate.

This new electoral structure is related to the rise of a new regime of accumulation: let us call it political capitalism. Under political capitalism, raw political power, rather than productive investment, is the key determinant of the rate of return. This new form of accumulation is associated with a series of novel mechanisms of ‘politically constituted rip-off’.footnote2 These include an escalating series of tax breaks, the privatization of public assets at bargain-basement prices, quantitative easing plus ultra-low interest rates, to promote stock-market speculation—and, crucially, massive state spending aimed directly at private industry, with trickledown effects for the broader population: Bush’s Prescription Drug legislation, Obama’s Affordable Care Act, Trump’s cares Act, Biden’s American Rescue Plan, the Infrastructure and chips Acts and the Inflation Reduction Act.footnote3 All these mechanisms of surplus extraction are openly and obviously political. They allow for returns, not on the basis of investment in plant, equipment, labour and inputs to produce use values, but rather on the basis of investments in politics.footnote4 This new structure is the real basis of Piketty’s main finding: that the rate of return on capital now outstrips the rate of growth (although Piketty himself, in our view incorrectly, presents this as a return to capitalist normality after the exceptional period of the long boom).footnote5

The rise of political capitalism has profoundly reconfigured politics. At the elite level, it is associated with vertiginous levels of campaign expenditure and open corruption on a vast scale. At the mass level, it is associated with the unravelling of the previous hegemonic order, for in a persistently low- or no-growth environment––‘secular stagnation’—parties can no longer operate on the basis of programmes for growth. They cannot therefore preside over a ‘class compromise’ in the classic sense. In these conditions, political parties become fundamentally fiscal rather than productivist coalitions. Before going on to hypothesize how these coalitions work, we should first clarify the terms we use for class analysis.

2

Social classes, in our view, are structural positions linked by relations of exploitation. The dominant class extracts labour effort from—that is to say: ‘exploits’—the subordinate class. That labour effort is the basis of the dominant class’s control over the social surplus, which in turn accords it a leading role in determining the overall developmental dynamic of the society in question. Different class structures emerge from the qualitatively distinctive ways in which dominant classes extract the labour effort of their subordinates. For example, under capitalism, owners of means of production typically extract labour effort from workers in the production process after the purchase of labour power—the capacity to work—in a market. In contrast, under feudalism, lords typically do not extract labour effort in the actual production process but subsequent to it, through the application or threat of force. Several points follow from these general positions.

First, the purpose of ‘class analysis’, in our view, is to identify the nerve centre of the entire social order with a view to its possible transcendence. It is not, therefore, pace the late brilliant Erik Olin Wright, a theory of ‘social stratification’, or a procedure designed to provide a social cartography of ‘life chances’. In fact, the categories of mainstream social science are far better at doing that than is class analysis. Olin Wright’s work constitutes a tacit admission of this, in that his ‘class map’, which is organized according to the criteria of property, authority and expertise, is unrelated to his underlying Marxist theory of what class is: a set of interlocked positions constituted by relations of exploitation.footnote6 Thus, especially under capitalist conditions, there may be gaping differences in ‘life chances’, income and lifestyle within the working class. Indeed, in the normal course of affairs, we would expect real class relations to be almost invisible as an everyday reality to most social actors, most of the time.

Second, and relatedly, in our usage the expression ‘class politics’ refers to the politicization of the main relationship of exploitation in the class structure under discussion. In capitalist society, this means the politicization of the wage-labour/capital relationship—and, in particular, attempts to exert political control over how the social surplus is invested. Class politics in this sense is a rare event; in advanced-capitalist societies, most politics tends to be non-class politics, as explained in Thesis One below. Finally, our argument is that a new structure of exploitation is in the process of emerging in the advanced-capitalist world; accordingly, we must also be witnessing the emergence of a new class structure, axed around relations of ‘politically engineered upward redistribution’. We have tried, however briefly and telescopically, to characterize these new class relationships using the notions of fiscal coalitions and status groups. To grasp their specificity we need to place the contemporary moment in an appropriate theoretical and historical perspective.

3

Thesis One. A new non-class, but robustly material, politics has emerged since the 1990s. The us political scene has long displayed a profoundly paradoxical aspect: while ubiquitously structured by class, it is marked by an almost complete absence of ‘class politics’.footnote7 The parties, at their apexes, minister to different fractions of capital, but at their bases are oriented to different fractions of workers. Thus, neither the Republican nor the Democratic Party is, or has ever been, a ‘working-class party’; it is correct to interpret these parties as parties of capital. Yet despite this fundamental orientation, they must both seek to appeal to the material interests of those who ‘own only their own labour power’, since this sector makes up the vast majority of the American population. Any party that competes in electoral politics must to some extent respond to working-class interests. Despite the talk of identity politics and ‘post-material values’, us politics has a clear material mass base. But it is not a class politics, because naturally neither Democrats nor Republicans seek to mobilize the many workers who vote for them against capital; nor do they attempt to exert effective political control over capital, especially in the era of ‘political capitalism’. Thus we have, in our formulation, material-interest politics without working-class politics.

This interpretation is rooted in a particular understanding of the relationship between working-class politics, class structure and class formation. We argue that class structure within capitalism under-determines class politics. This under-determination, inherent in the structure of the relations of exploitation under capitalism, is particularly acute in the us for historical reasons, two of which are worth emphasizing: the emergence from the 1870s of a racialized system of labour control in the South (‘Jim Crow’); and mass immigration, which created a basis for ‘ethnic’ stratification.

4

At the most abstract level, workers pursuing their economic interests under capitalism can choose between two main strategies: individualist and class-collaborationist, or collective class-based action.footnote8 Through the first strategy, in some ways the most natural one, workers pursue their interests as owners of the ‘special commodity’, labour power. This can assume many forms; but fundamentally, all non-class worker material-interest politics is centred on improving wages and job opportunities within the system of private appropriation. This is not working-class ‘class politics’, because in this politics workers neither act, nor conceive of themselves, as a class. At one pole of this non-class politics stands collective bargaining; at the other, anti-immigrant and racist politics. In the contemporary us, with its large group of relatively highly educated workers, credentialling and the defence of the value of credentials is also a common non-class strategy. The various fractions of the working class organized to protect the value of labour tend to coalesce as what Weber termed ‘status groups’, deploying political-ideological means to manage competition. This form of politics tends to fragment and isolate workers from one another.

The alternative is working-class ‘class politics’. Workers pursuing a class strategy link redistributive demands to a broader attempt to exert political control over the social surplus produced by workers and appropriated by capital. They also conceive of themselves as members of a class, in a society divided by classes. The pursuit of working-class politics is always risky for individual workers, as it requires a large group to act in solidarity. It is always tempting, and often highly rational, for individuals to withdraw from the class strategy and opt for the status-group approach, in an attempt to increase returns on the sale of their unit of labour power. Meanwhile, the only mechanism that can hold workers together as a ‘class’, rather than as a ‘sack of potatoes’ of sellers of labour power, is class struggle. The significance of class struggle lies, therefore, not only in the contest between labour and capital, but just as centrally in the struggle to transform the inherently isolated and atomized owners of labour power into a collective agent, to break through the rigid carapace of the commodity form and set in motion the working class as a historical subject. As Rosa Luxemburg put it, drawing the lessons of the 1905 Russian Revolution: ‘The proletariat require a high degree of political education, of class consciousness and organization. All these conditions cannot be fulfilled by pamphlets and leaflets, but only by the living political school, by the fight and in the fight, in the continuous course of the revolution.’footnote9 Working-class class politics, in short, is constituted in the context of class struggle.

Working-class politics in this sense has been a highly unusual occurrence in us history. There were only two brief spells of it in the twentieth century. The first, which ran from 1934 to 1937, saw the passage of the 1935 Wagner Act (gutted in 1948). The second, extending from the mid-60s to the early 1970s, brought the Voting Rights Act and the Great Society programmes. But these bouts of class politics quickly petered out. The reformist political layers they threw up were able to win some material gains for ordinary people, but only under the favourable economic conditions of the long post-war boom. When this faded, giving way to the long downturn, bureaucratic union leaders and Democratic politicians could only impose concessions on their mass base.

5

Since the 2010s, there has been an uptick in class struggle, but members of the working class continue to pursue their interests overwhelmingly as owners of labour power, rather than as a class. This is not to say that nothing has changed. For one thing, there is now a wider variety of bases from which class-collaborationist or status-group politics can be pursued.footnote10 Up until the 1980s, these politics could broadly be described as reformist, or ‘social-democratic’—premised, like all social-democratic politics, on the prospect of economic growth. But the politics of the present period does not hold out even the hope of growth. It is a politics of zero-sum redistribution, primarily between different groups of workers. It is distinct from social-democratic politics, not because it is not a class politics—that is equally true of social democracy––but because it is not a growth politics. Thus the two main us political parties no longer appear as alternative growth models, but rather as different fiscal coalitions: maga politics, which seeks to redistribute income away from non-white and immigrant workers, and multicultural neoliberalism, which seeks to redistribute income toward the highly educated.footnote11 Both tend to atomize and fragment the working class.

6

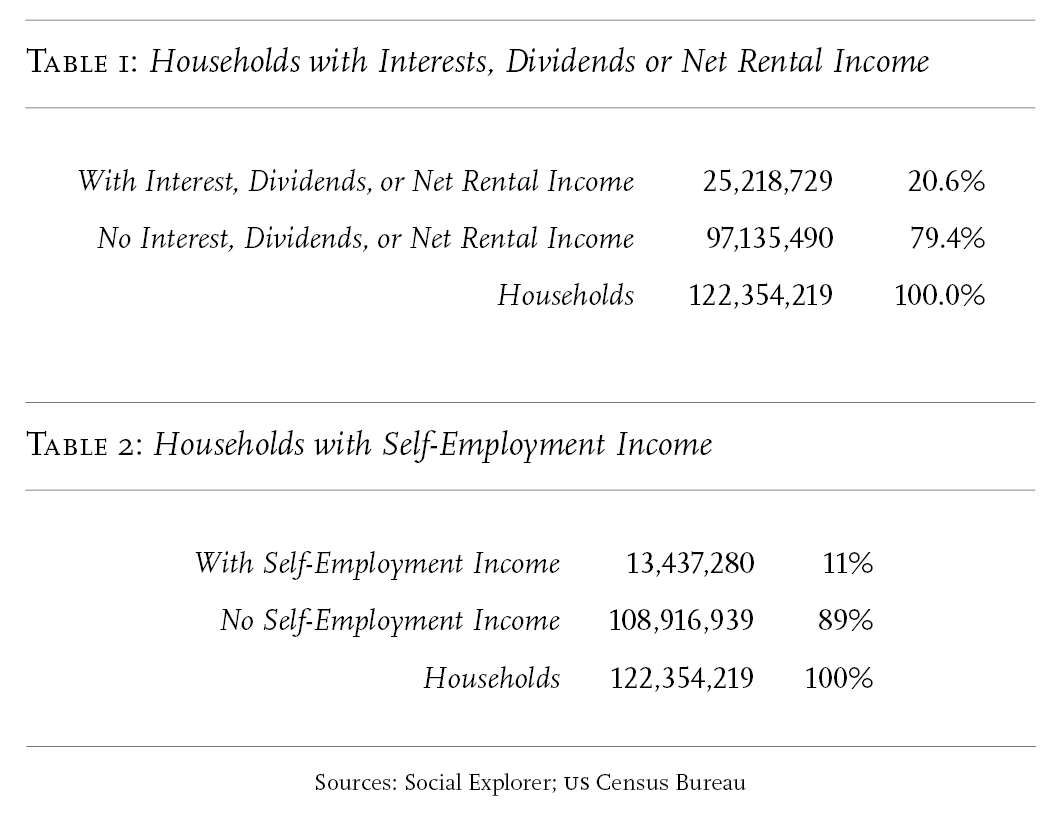

With this conceptual framework in mind, let us offer some basic evidence about the character of the us working class. As a first approximation, the working class can be conceptualized in terms of its relationship to the main assets of society. Workers are all those who do not enjoy income from rents, dividends or interest payments. As Table One shows, only 21 per cent of households are asset owners (excluding home ownership), leaving approximately 79 per cent of households with no access to such forms of income. It might be thought that this overstates the size of the working class, for perhaps there exists a large self-employed group that enjoys neither assets nor wage income. But as Table Two shows, only about 11 per cent of households has any self-employment income, and many of these are undoubtedly disguised wage-earners. Putting these two pieces of evidence together, we can establish a lower bound for the quantitative extent of the working class. Even assuming that all households with self-employment income are owners of their main means of production and do not rely on wages, 68 per cent of the us population would be in the working class. Accordingly, at this level of generality, Marx’s claim that the nineteenth-century working class constituted the ‘vast majority’ of capitalist society remains correct.footnote12

7

Nevertheless, it would be the height of dogmatic stupidity not to recognize the profound divisions within the working class—divisions which have never been adequately mapped within the Marxian tradition. The problem can only be hinted at here with a few empirical signposts, pointing to education, labour-market sectors and ‘race’. To start with the phenomenon of education: it is commonplace in the us today to equate the ‘non-college-educated’ with the ‘working class’. On theoretical grounds this conflation is highly problematic, because ‘education’ is not a resource comparable to asset ownership. A degree on the wall, from however prestigious an institution, produces no income. In our view, any concessions to notions of ‘cultural capital’, ‘human capital’ or the ‘professional-managerial class’ are ultimately a capitulation to one of the oldest ideological canards of bourgeois society: the idea that such societies are made up predominantly of independent proprietors selling their wares on the market. Even the mostly highly educated worker, if she or he lacks assets, must enter into a wage relationship—that is, they must subordinate themselves to capital in order to gain a livelihood.

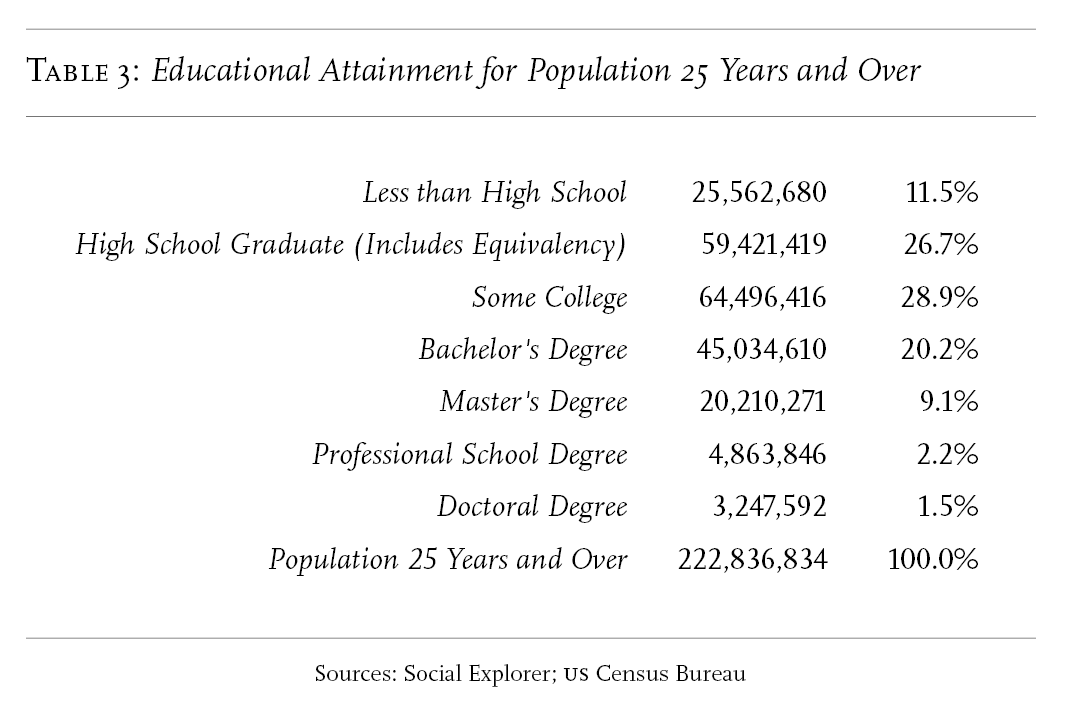

This does not mean that education is economically irrelevant; on the contrary, in the us, education is clearly correlated with higher wages.footnote13 The distribution of the population according to the possession, or not, of a higher degree thus says something important—not so much about the working class, but about a significant fraction of it. With this in mind: what percentage of the us population enjoys, at least potentially, the benefits of a higher degree? As Table 3 below shows, a third of the us population over 25 has a ba certificate, and around 38 per cent have only high school or equivalent. This leaves 29 per cent having ‘some college’, often a two-year ‘associate’s degree’ in a professional skill, such as nursing. At the higher levels of the tertiary education system, the percentages are quite small. Only 9 per cent have a master’s degree, and barely 2 per cent have either a ‘professional school degree’, such as the md required to become a medical doctor, or a ‘doctoral degree’, such as a PhD. It is worth emphasizing that a plurality of the us population faces the labour market as basically unskilled labour.

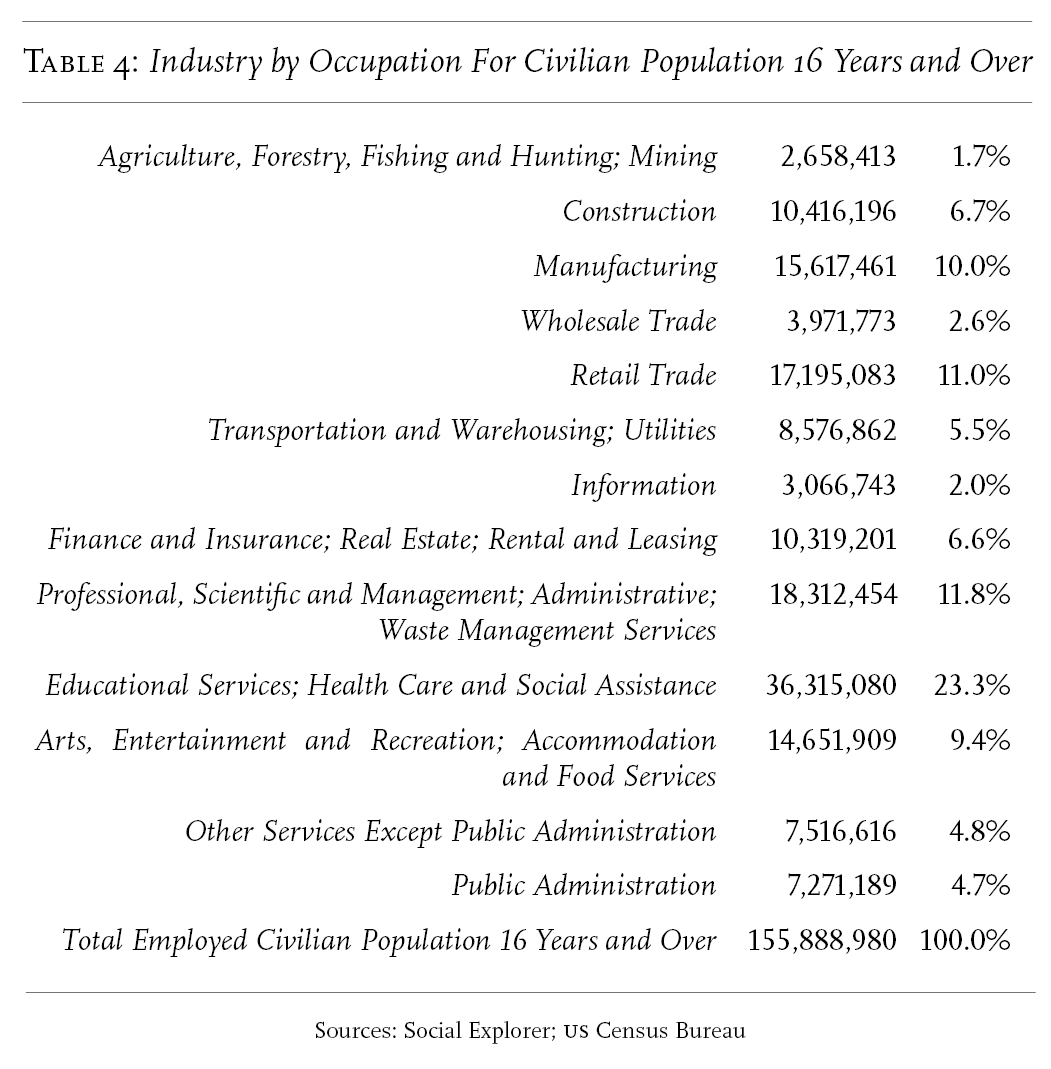

The working class is also heterogeneous in terms of its sectoral composition. Workers in the industries of the ‘historical working class’ make up a distinct minority: ‘Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing and Hunting, and Mining’, ‘Construction’, ‘Manufacturing’, and ‘Transport and Warehousing, and Utilities’ together account for approximately 24 per cent of the employed population, while the single category of ‘Educational Services, and Health Care and Social Assistance’ constitutes over 23 per cent. A substantial portion of those working in these fields likely have some sort of credential.

The us working class is of course also deeply split by ‘race’. About 70 per cent of the population identifies as ‘white’ and around 13 per cent as ‘black’, but regional variations are wide; for example, 56 per cent of Californians identify as ‘white’ and 6 per cent as ‘black’. Furthermore, the category of ‘Latino’ or ‘hispanic’ cuts across the ‘white’ category. Nationally about 10 per cent of the ‘white’ population identifies as ‘hispanic’ or ‘Latino’, meaning that ‘non-hispanic whites’ make up about 60 per cent of the us population, and around 40 per cent in the large immigrant states of California, Texas and Florida. These identities famously constitute a fertile terrain for non-class or status-group politics.

How to summarize this basic configuration? The working class, understood as those who do not own assets and therefore must subsist on wage income, make up between 68 and 80 per cent of all us households. But this class is profoundly split by education level, sector of economic activity and ‘race’. These divisions are rooted in the logic of an overall configuration in which owners of capital are effectively exempt from attempts at meaningful redistribution. This perspective allows us to bring together education and race in a single conceptual framework. ‘Credentialling’ and ‘race’ can be thought of as forms of social closure that emerge within a us working class organized primarily in terms of internal redistribution. To put the point as pithily as possible, ‘whiteness’ or ‘nativeness’ should be understood as the ba of the non-college-educated, and possession of the ba should be understood as the ‘whiteness’ or ‘nativeness’ of the college-educated.

8

Thesis Two. Bidenism offers Keynesianism without growth. Bidenism is a peculiar phenomenon. For an accurate characterization, we first need to acknowledge the ambitious scale of the Administration’s agenda. The draft Build Back Better legislation passed by the Democrat-controlled House in September 2021 was based, like its predecessors, on largesse distributed through political means to capital; at $2.2 trillion, it not only rivalled the cares Act in size but would have introduced new moves, however limited, towards universal health insurance, paid family leave, subsidized childcare and early childhood education. Its shrunken descendant, the Inflation Reduction Act (ira) signed into law in August 2022, provides $738 billion over ten years, through a fiscal mix of two-thirds tax cuts, one third direct expenditure, to stimulate green capitalism—solar and nuclear power companies, agribusiness, home-energy efficiency, electric vehicles—lower the price of medicines and extend the existing subsidy to the Affordable Care Act ($64 billion, over three years).

The new agenda embodies two peculiarities, however. The first concerns its conditions of emergence. Although the American version of the Keynesian welfare state was never the direct consequence of class politics—it had at least as much to do with wartime mobilization—historically, it was premised on a prior wave of working-class militancy. By contrast, the post-2020 expansionary policy has no such basis; it is largely a fortuitous response to the Covid pandemic and perhaps also to the rivalry with China—indeed, the continuity between Bidenomics and Trumponomics lies precisely here.footnote14 The second peculiarity is the economic environment in which the new agenda operates. Every other Keynesian welfare state has been based on a booming economy; Bidenomics, in contrast, is a programme of deficit spending without growth. There is very little evidence of a real return to American manufacturing profitability.

9

How then are we to understand this strange creature? A brief narrative of how Biden came to occupy his current position may be useful here. Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign in 2016 was as strongly committed to neoliberalism as the three prior administrations had been—appealing to the Democratic Party’s natural constituencies among the credentialled fraction of the working class in the twin terms of expertise and diversity, but proposing virtually nothing by way of economic growth. Had Clinton won, this would have represented the ongoing hegemony of multicultural neoliberalism in its pure form.

Trump’s surprise victory blocked that path. This electoral break with multicultural neoliberalism was then compounded by the pandemic. Although Trump himself resisted at every step of the way the obvious and rational response to the Covid-19 crisis, his Administration nonetheless opened a path towards a new form of politics due to the unavoidable necessity of countering the pandemic. The Federal state intervened massively to sustain the lives of many ordinary working-class Americans—the opposite of what Trump and his collaborators proclaimed they wanted. This produced a bizarre situation, in which Trump discredited the very policies his Administration had pursued, especially with regard to masks and mass vaccination.

These contradictions were wrongly read as personal foibles. In fact, Trump’s erratic behaviour concentrated and exemplified the contradictory historical circumstances that led the Republicans willy-nilly to become the first American party to make moves toward a guaranteed basic income. Trump’s constant self-discrediting, his ludicrous formulations about bleach as an antidote to Covid and so on, were an attempt to avoid acknowledging that the policies forced upon him by the pandemic were appropriate and effective. His Administration could legitimately claim some credit for the extraordinarily rapid development of effective vaccines—but as Trump himself discovered, this could seriously alienate the maga base.footnote15

Biden emerged triumphant on the ruins of Clinton’s project, once behind-the-scenes moves by the Democrat leadership had orchestrated the defeat of Bernie Sanders. Bidenism is also, however, and crucially, a specifically post-Trump phenomenon. To win in 2020, Biden had to take advantage of the historical contradictions that were biologically embodied, as it were, in Trump’s mindlessness. Initially Biden therefore had the wind at his back, because he seemed the best available political leader in the fight against Covid. This in itself forced a break beyond Clinton’s multicultural-neoliberal politics, even though Biden had been a Delaware neoliberal stalwart since the 1990s. As his domestic agenda shows, Biden came to embody, briefly and accidentally, something like a new New Deal. The Trump–Biden fiscal response to the Covid recession between March 2020 and March 2021 was over $5 trillion, five times greater than the 2008 fiscal stimulus, and almost a quarter of gdp. Crucially, $1.8 trillion of this went straight to individuals and households via stimulus checks and unemployment benefits, topped up by $600 a week between March and July 2020, with a further round of $2,000 checks disbursed in January 2021.footnote16 To this, Biden’s subsequent legislation in 2021–22—the Infrastructure Act, chips, the ira—added another $2 trillion.

In a strange way, then, Covid represented a functional equivalent of the sort of class politics that had helped to generate the New Deal and Great Society policy packages. But the peculiarities of this agenda’s genesis also marked its limits. For although the Biden Administration—which had taken care to flatter and incorporate willing Sandernistas, not least Sanders himself—put forward policies that were objectively pro-worker, this was all done sotto voce, within the constraints imposed by a complete renunciation of any attempt to redistribute profits. The fate of the Biden experiment was also determined by the prevailing economic conditions. The pursuit of a quasi-New Deal fiscal programme without the requisite capitalist growth has predictably contributed to rising inflation, already stoked by pandemic-era demand shifts and supply-chain disruptions, followed by the food and fuel price spikes of the Ukraine war. In turn, the cost-of-living crisis has discredited Biden domestically. Thus, the paradox of Bidenomics: a relatively pro-worker policy package has led to deep unpopularity, with midterm disapproval ratings on a par with Trump’s.footnote17

10

Thesis Three. The hypothesis of ‘class dealignment’ is an inadequate framework for understanding American contemporary politics. According to this approach, whose most sophisticated and informed left exponent is Matt Karp, at one time us politics was class politics, but now it is structured by identity.footnote18 The ‘class dealignment’ analysis undergirds a politics that would seek to repolarize the population in class terms, which, so the thinking goes, was the basis of reformism in its New Deal and Great Society manifestations. This position both over-emphasizes the class character of American politics prior to the collapse of the New Deal coalition and under-emphasizes its robustly material but quite obviously non-class basis in the current period.

To reiterate: reformist or welfare-state policies in the us (and elsewhere) were never the direct result of class insurgency. At least as important was wartime mobilization, which not only lifted the us out of the Great Depression but also produced many of the era’s most ambitious policies: the build-out of the veterans’ hospital system, for example, or the gi Bill. Furthermore, the continuation of the comparatively minimal American ‘welfare state’ found its key basis of support not so much in the working class as in the stratum of reformist officials that emerged from the rare and brief bouts of class politics mentioned above. The political project of this mid-century group of union officials and Democratic Party operatives was oriented towards ensuring the continuing profitability of American capitalism, since they rightly saw profitability as the cornerstone of their own viability. This stratum, therefore, consistently sought to impose individualistic and collaborationist solutions on workers, seeing their autonomous mobilization as a threat. As the long boom turned into the long downturn, it offered little but austerity to the workers it ostensibly represented. There is thus no basis for conflating the Keynesian welfare state in the us with class politics.

Second, the notion of class dealignment offers no positive description of the basis of American politics today. While it captures the important fact of Democrats’ continuing struggles to attract white workers—and, increasingly, non-white workers—without a college degree, it fails to explain how white workers as white workers, or native workers as native workers, are being remobilized in the Republican coalition. Nor does it explain the equally puzzling fact that the highly educated are being remobilized in the Democratic coalition.footnote19 Perhaps the most striking thing about American politics today is that the Republican Party has made a concerted and highly successful effort to court the less-educated fraction of the working class; indeed, the political fortunes of the gop are increasingly linked to this layer.footnote20 But to describe these tectonic shifts as rooted in ‘identity’ is misleading, or at least highly partial.

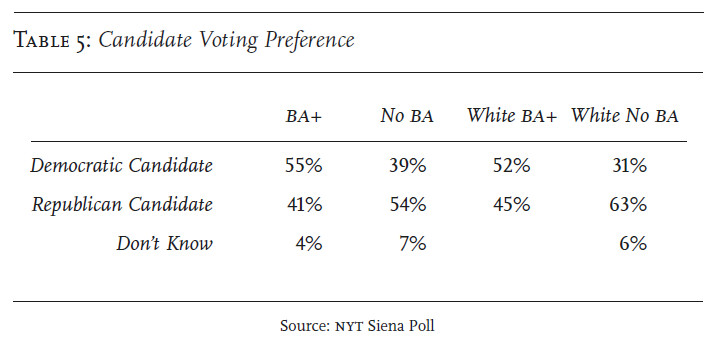

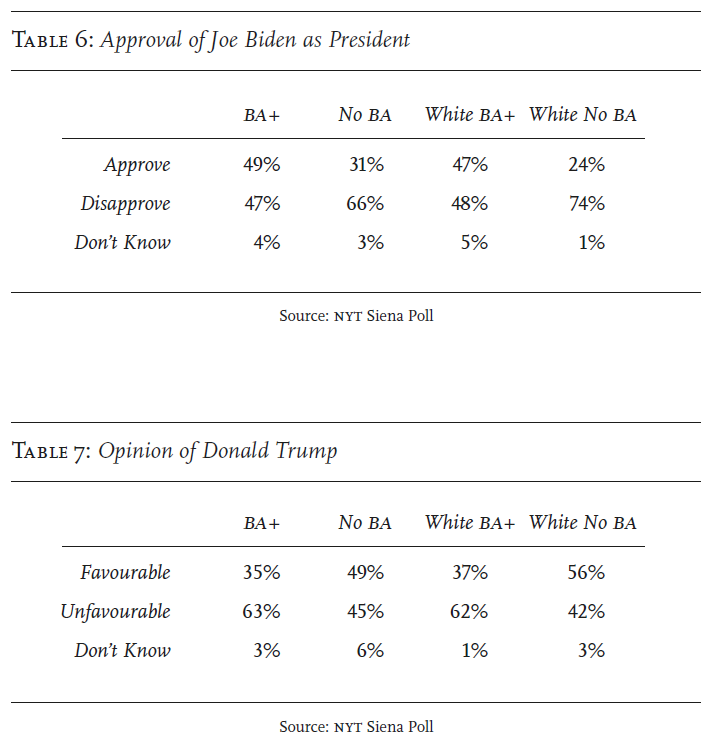

The evidence here is now overwhelming. Tables 5, 6 and 7 indicate the nature and extent of the problem for the Democrats. In the generic congressional ballot, ba holders lean to the Democrats by about 14 points. Non-ba holders are a mirror image of this, leaning Republican by about 15 points. Among white ba holders the split is similar, but white non-ba holders indicate a preference for the Republican candidate by a 32-point margin. A similar picture emerges in terms of approval ratings for Biden and Trump. Biden’s approval is completely underwater among voters without a college degree: two-thirds of non-ba holders disapprove of him, a figure that rises to almost three-quarters among white non-ba holders. In contrast, among ba holders his approval hovers at around 50 per cent. The patterns for Trump are the inverse of this. Among ba holders as a whole Trump is underwater by 28 points, while among non-ba holders he has a slight advantage. The pattern is similar for white ba holders, where he is 25 points down. Among white non-ba holders, Trump has a 14-point positive margin.

This shift of white workers without a college degree to the Republican Party is best understood not as a process of class dealignment, but rather as the consequence of the gop’s successful bid to appeal to the interests of a particular fraction of the working class in nativist and racist terms.footnote21 The key point is that this segment’s move to the Republicans should not be explained in terms of attitudes or prejudices; rather those attitudes should be seen as resulting from this class fraction’s objective situation. The organization of the white working class as white, or native workers as native, is in many ways a rational strategy for those workers who have the opportunity to constitute themselves as such, in a context where class identity is nowhere evident. By keeping out immigrants, and keeping down non-whites, the white working class, or native working class, seeks to increase the value and attractiveness of its labour power. This is not to imply that such a strategy is based on an accurate analysis, or that it is likely to succeed. The point is simply that the policy preferences of the non-college-educated are understandable pragmatically without having to attribute to this group a fanaticism which it does not hold.

The same logic should be applied to those relatively highly educated workers who vote for the Democrats. This is a step that very few analysts take. They tend instead to argue, implausibly, that the college-educated are motivated by ‘values’ rather than economic interests. But the core ‘values’ that these voters espouse chime remarkably well with their material interests, which lie in the valuation of expertise. This is probably most conspicuous in the embrace of science as an ideological value. Although clearly less regressive than its maga counterpart, this neo-technocratic ideology performs an analogous social function in articulating a strategy for increasing the value of the particular type of labour power—credentialled, rather than white—that is widespread in the Democratic coalition. And it is, of course, just as little a manifestation of working-class politics as its Republican counterpart. As mass organizations, the two parties are therefore anchored in different parts of the working class: the Republicans in its less educated fraction, and Democrats among the credentialled. In both cases, their appeals are framed in terms that cast workers as petty-owners of labour power. This mode of politics tends to further fragment the working class and to push working-class class politics further away—even though, indeed because, it appeals to highly specific material interests.

11

Thesis Four. The Democrats’ relative success in the 2022 midterms is a reflection of its particular social base. Given the character of the mass bases of the Republican and Democratic parties, it is unsurprising that Democrats now seem to outperform the Republicans at midterm elections. They will undoubtedly continue to do so because the Democrats’ base, being more educated, is more likely to be engaged in electoral politics. While the gop currently benefits most from the inequities of the Constitution, Republicans now have the disadvantage of being firmly tied to the fraction of the electorate that is less likely to turn out for the midterms.footnote22 In the terms of our analysis, the Democrats’ very success in this electoral cycle is premised upon, and likely to reinforce, the fragmented nature of the us working class, rendering it even less likely to act as a coherent social force. To put the point as directly as possible: Democrats do not turn out their base by appealing to working-class politics, but rather by appealing to workers in explicitly non-class terms.

12

Thesis Five. The American left is in the grip of three illusions about domestic politics. In understanding us politics, it is of the utmost importance to grasp the electoral strategy of the Democratic Party. In this regard, three common illusions have plagued left analysis. The first is the notion that the obvious path to electoral success is to appeal to the American working class in ‘class terms’. The Democrats have rarely done this, even, indeed especially, in their New Deal heyday. This illusion relies implicitly on a prior misconception: that the Democratic Party has been an electoral failure in recent years. In fact, the question is not why the Democrats haven’t won more seats, but why they have done so well in the last three cycles, since 2018. The 2022 midterm results, which seem again to have defied much common-sense thinking, were successful by comparable historical standards. They followed a 2020 election in which the Democratic challenger defeated an incumbent president with a super-energized base, who won more votes than any other candidate in history—apart from the one who defeated him.

It is therefore incorrect to present the Democrats as irrationally pursing a non-class strategy. The current Democratic Party has no interest in appealing to its political base in class terms. The party’s success is premised on winning over a fraction of the working class in explicitly non-class terms. Given the Democrats’ actual constituency––that fraction of the working class dependent on credentials to increase the value of its labour power––its electoral strategies and candidates are hardly irrational; they have been strikingly effective. Democratic operatives quite logically will continue to intervene in Republican primaries to promote the most outlandish candidates, as they did in 2022, because they are easier to defeat on the basis of straightforward claims to represent rationality against insanity. That was the obvious lesson that every competent operative drew from the midterms. In other words, Democratic Party electoral success is likely negatively related to class politics, such that the re-emergence of such a politics would pose an electoral threat.

The second illusion common in left analysis is the idea that the Biden Administration has pursued timid, weak or disappointing domestic policies. This flies in the face of the whole historical experience since early 2020. In fact, no administration since lbj has proposed the sort of domestic initiatives Biden has; this would have been absolutely clear if the Administration had enjoyed a slightly greater advantage in Congress. As discussed above, Bidenism has been beset by contradictions, but it is not lacking in ambition on the domestic front.

The third, corollary illusion puts together the two preceding ones to claim that Biden’s unpopularity and the party’s electoral struggles derive from his policy timidity. But since Biden, and the Democrats more broadly, have actually been remarkably successful in electoral terms, and since they have also pursued some strikingly ambitious policies, this position can only be described as a compounded illusion. The political problems Biden has faced in fact derive from the constraints of political capitalism as a system of accumulation. The new political structure to which this has given rise prevents the construction of hegemonic growth coalitions and the associated phenomenon of massive electoral landslides. It produces instead a vicious, narrowly divided politics of zero-sum redistribution, largely axed on conflicts of material interest within the working class.

13

Thesis Six. Positive-sum class compromise is impossible in the current period. The basis of the welfare state, both in the us and Europe, has always been high profitability, and high rates of investment, in manufacturing. But manufacturing profitability and investment remain weak. (Even the supposedly most dynamic sectors of the new economy are in the throes of a crisis.) Political capitalism remains firmly in place, meaning that redistribution from capital to labour will be extremely difficult, if not impossible, because of the dependency of profits on politically engineered upward redistribution. It is perhaps this fact, above all else, that explains the sudden return of inflation. Inflation is what one gets when one pursues deficit spending in the absence of a dynamic capitalism.

14

Thesis Seven. Bidenism’s natural ideology is progressivism, not social democracy. There is one specificity of Bidenism that we have not yet emphasized sufficiently: its distinctive ideological profile. In direction and tone, the Administration’s policies represent the interests of the educated fraction of the working class within the context of political capitalism because that is the party’s obvious base. In this, Bidenism most strongly resembles late nineteenth-century ‘Progressivism’. The Administration’s social ideal is a market economy undistorted by monopolies and managed by an open, meritocratically recruited and diverse elite. The tool used to implement this vision is the regulatory state, including a metastasizing diversity, equity and inclusion bureaucracy which has the side benefit of providing well-paid perches for members of the educated working class itself. The watchwords of this project are ‘fairness’ and ‘justice’: terms which do not describe a social ideal at all, but a state of affairs among individuals.

All of this is worlds away from the notion of democratic control over the social surplus. We need a language to describe the new Bidenist project; ‘neo-progressivism’ is perhaps the best term. In content and intention it remains as far from socialism as its social-democratic and neoliberal forebears; but it is nevertheless a distinctive historical formation which must be theorized and studied on its own terms.

15

A final note. We offer these theses in an experimental and provisional spirit. Though rough and unfinished, they hopefully indicate at least some of the central issues that must be tackled head-on if the current, exceedingly odd, political period is to be grasped. Time-worn shibboleths and old patterns of thought will be inadequate to navigating whatever is coming next.