There is no shortage of epithets aimed at grasping the transformations taking place within global capitalism under the impact of the ongoing technological revolution. Algorithmic capitalism, cognitive capitalism, communicative capitalism, data capitalism, digital capitalism, frictionless capitalism, informational capitalism, platform capitalism, semiocapitalism, surveillance capitalism and virtual capitalism have all been proposed, to name but a few. Of late, this categorization project has posited a rupture that leaves capitalism itself behind, not in the spirit of an advance, but as a regression to a world of data barons and user-serfs: digital feudalism, techno-feudalism, information feudalism, neo-feudalism have become new watchwords on both left and right, attracting the bracing attention of Evgeny Morozov, whose ‘Critique of Techno-Feudal Reason’ appeared in the last number of nlr.footnote1

Morozov concedes that uses of the term may be largely rhetorical, capitalizing on feudalism’s ‘shock value’ and meme-friendly affect. But he also sees it as the symptom of an intellectual failure to conceptualize the most advanced sectors of the digital economy, where ‘the left’s brightest minds still find themselves very much in the dark’.footnote2 If giant info-tech platforms like Google, Amazon and Facebook don’t earn their profits through old-fashioned capitalist exploitation of their workers, should they be seen as new-model landowners—non-productive rentiers, leveraging their network dominance and monopoly hold over data-sets and algorithms to extract advertising revenues generated elsewhere in the capitalist economy? Or, as Shoshana Zuboff argues in The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, are they getting rich by extracting and expropriating our user data through means of algorithmic surveillance, a form of ‘digital dispossession’ that feeds a new logic of accumulation, akin to the model of ‘accumulation by dispossession’ hypothesized by David Harvey in The New Imperialism? Or again, as Cédric Durand puts it in Techno-féodalisme, have the tech giants effectively subordinated us to their rule through their control over information and knowledge (‘intellectual monopolization’), on the basis of which they develop ever-more sophisticated means of predation, à la Veblen, for appropriating surplus value without being involved in the productive process?

Morozov himself wants to have it both ways. Google’s monopoly over the data it is gathering may have a rentier logic, but the corporation’s business model largely rests on producing a commodity, the search result—‘real-time access to vast amounts of human knowledge’—even if it then gives this away for ‘free’, so as to sell advertisers targeted access to its users. But this is not classical intellectual monopolization, since the web pages Google indexes remain the abstracted property of their owners—who, admittedly, are made to forgo extracting any licensing fee from Google itself. In addition, quite unlike Veblen’s Belle Époque predators, or unproductive feudal lords, Google and its peers invest vast sums in research and development. Grounding his argument in the landmark debates about capitalism’s distinguishing features, Morozov sides (more or less) with the world-systems theorists and Harvey’s later work in proposing a more expansive concept of accumulation, encompassing both dispossession and exploitation, against Robert Brenner’s ‘elegant and consistent’ model of a core competitive logic. Capitalism has undergone no rupture; it is ‘moving in the same direction it always has been’, leveraging whatever resources it can mobilize. If Google produces search-result commodities, ‘there is no great difficulty in treating it as a regular capitalist firm, engaged in normal capitalist production’—along with other time-honoured tactics like buying influence on Capitol Hill and swallowing the competition.footnote3

Yet neither Morozov’s same-as-ever capitalism nor Durand’s techno-feudalism succeed in grasping the novel dynamics of a capitalist sector founded on networked computing-machines, tracing its conception to the us military-industrial complex. Nor does Zuboff’s idea of ‘digital dispossession’—or for that matter Harvey’s original ‘accumulation by dispossession’—fully fathom the qualitative transformations these new practices entail. To be dispossessed suggests there must have been an earlier form of possession that has been violated. This becomes more complex when the possession in question takes the form of data. In what way does one ‘own’, say, a search term entered into Google? Or the string of digits that represent one’s locational coordinates, as calculated by interactions between a mobile phone and orbiting satellites? My physical location may be abstracted to something like -30.177092,153.185340 digital degrees; but these—and the many other data traces that the tech-titans use—do not exist before the web of devices and sensors abstract them into the digital realm. They only make sense through the powerful abstractions of the Global Positioning System, the planet-enmeshing apparatus of networked computing-machines and gps satellites, travelling at nearly 9,000 mph, 12,000 miles above the earth’s surface, which require the application of Einstein’s theories of relativity to function. This techno-scientific process renders the planet’s surface as a general equivalent, within which the digital degrees drawn from my embodied location are produced on a more abstract level, with this process in turn producing a new organizational capacity. We need theories that can critically analyse these new levels of abstraction and map the qualitative transformations taking place.

Piloting accumulation

In what follows, I outline an alternative approach. I argue that the concept of cybernetic capitalism supplies a framework that can encompass both the deep historical processes and the radical discontinuities of our current conjuncture, conjugating the analytically distinct levels of speculative finance and techno-scientific enquiry, concentrations of wealth and social power and disembodied forms of communication.footnote4 The term ‘cybernetic’ derives of course from the Greek kubernētikós, or ‘steersman’, etymologically related to ‘govern’. Plato’s ship of state famously required a true pilot, combining knowledge of the stars and winds with commanding authority. But the coinage of ‘cybernetics’ in the 1940s, emerging from the work of an elite group of scientists, engineers and technicians at the heart of the us military-industrial complex, emphasized instead the unity of communications and control.footnote5

Any theorization of communications will need to foreground the concept of abstraction—in the sense, not of a concrete-abstract dichotomy, but as a material social practice with deep historical roots. Writing itself is an abstraction of speech, translating it into symbols that can be embedded in an external technology, such as a clay tablet. The means and forces of abstraction appear to have undergone an uneven process of intensification across human history but reached new heights with the emergence of early modernity in Europe in the ‘long sixteenth century’ (c.1450–1640), manifested in the rise of print technology in communications, the scientific method for inquiry, double-entry bookkeeping in accountancy, perspective in painting and rationalized cartography in interpreting space, to name but a few. The ensemble of these practices facilitated expansion and extraction, centralization and concentration, acceleration and accumulation, underpinning the early history of capitalist modernity.

A key figure in this early ‘scientific revolution’ was the English statesman and philosopher, Francis Bacon (1561–1626). Bacon is credited with many things, being the ‘father of modern science’ for one, as well as being the first to conceive of a research institute, the first to imagine industrial sciences as a source of economic and political power, and the first technocrat. He was also a pioneer of science fiction. His incomplete utopian novel, New Atlantis, written in 1624 and published posthumously, imagined the workings of a state-sponsored scientific research institute on a fictitious Pacific Island. There the inhabitants practised Bacon’s experimental method of isolating natural phenomena in controlled settings where they could be subject to instrumental analysis and rational inquiry. Running with Bacon’s aphorism, scientia potesta est—knowledge is power—his successors studied nature in order to extract secrets that could lead to prediction and control, to establish the ‘Empire of Man’ over creation. This drive to dominate was central to what the American urbanist Lewis Mumford called capitalism’s ‘quest for power by means of abstractions’—a quest that would create enduring connections ‘with more vulgar forms of conquest, those of the trader, the inventor, the ruthless conquistador, the driving industrialist seeking to displace natural abundance and natural satisfactions with those he could profitably sell.’ Abstraction became problematic, as it facilitated dominion over nature, including human nature, and over other peoples.footnote6

The idea of abstraction is crucial to the concept of cybernetic capitalism. As a techno-science, cybernetics is concerned with communication and control between people and technology. Here it can be read as shorthand for a particular mode of inquiry—instrumentalized techno-scientific research, which creates new abstractions—combined with a mode of (disembodied) communication, via networked computing-machines, and a mode of organization: a distributed network, managed by centralized bureaucracies. These cybernetic features are combined with ‘capitalism’, shorthand for a mode of production—the rationalized and privatized bringing forth of goods so as to extract and concentrate the maximum amount of surplus in the hands of the owners of capital—combined with a mode of exchange—money, mediating relationships within financialized circuits—and a mode of consumption; or rather, intense levels of commodity overconsumption. The advantage of this more expansive ‘mode of practice’ framing over the more usual ‘mode of production’ is that it acknowledges the importance of other practices besides producing goods: communication, exchange, inquiry, consumption and organization, with each aspect of these having economic, political, cultural and ecological components.

An apex form

The origins of cybernetic capitalism, then, lie at the apex of the American national-imperial state, forged during the Second World War. Indeed, the dawning of the cyber-capitalist age might be dated to 21 seconds past 5:29 am—local time in New Mexico, us—on 16 July 1945. At that moment, ‘Trinity’, the first atomic bomb, was detonated in the desert. Plutonium atoms were torn apart in a nuclear reaction, releasing an immense amount of energy in the form of heat, light, sound and radiation, making the earth tremble, melting the desert sand into green radioactive glass and sending an immense mushroom cloud seven miles up into the sky. This rigorously calculated incident was a crucial moment in world history: techno-scientific forces now enabled people to reorganize the building blocks of matter. Twenty-three days after the Trinity blast, the us used their terrible weapons on the people of Japan. Three warplanes were sent to Hiroshima. The first carried the payload—the atomic weapon, ‘Little Boy’. The second was filled with scientists, equipped with sensors and instruments to measure the blast. The third carried photographers, to record the event. Hence science and surveillance literally flanked the world-historic atom-bombing mission. On their return the scientists fed their data into computing-machines, to calculate the success of their abominable human experiment.

The atomic explosion was only possible because nascent computing-machines—ibm’s Harvard Mark i—were available to crunch the vast number tables for the Manhattan Project. Computing-machines and nuclear weapons were born together, in the womb of war. The first general-purpose digital computer, eniac, was activated four months later, in December 1945; its first task was a mathematical test to ascertain the practicability of thermonuclear weapons, more terrible than the fission blasts that had annihilated Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The rise of the digital device brought into retrospective focus the analogue technologies that had preceded it, which literally bore an analogy to some natural phenomenon: for example, a hammer is analogous to a fist, an airplane wing to a bird’s pinions. Digital computing, by contrast, was fundamentally discontinuous, built on the binary of 1 or 0, ‘all or nothing’, on or off. The radical break of the digital had a place in the broader social pattern of increasing abstraction. Digital computers did not emerge from the history of labour and craft, but rather at the command of capital and the state. They could not exist at all without technological transformations that depended in turn upon the intensely abstracted theoretical work of intellectually trained computer scientists in us research laboratories.

As with the cybernetic mode of practice more broadly, this cohort of elite scientists and engineers had its origins in wwii, when the us mobilized massive government-sponsored research projects, run by both the military and civilian arms of the state, with the intensive involvement of some of the major corporations. If the origins of the military-industrial complex could be emblematized by any one person, the American engineer Vannevar Bush (1890–1974) is the likely candidate. Dean of the mit School of Engineering, founder of Raytheon, director of the war-time Office of Scientific Research and Development and an initiator of the Manhattan Project, Bush’s presidential report, Science, the Endless Frontier, with its telling colonial metaphor, was one of the founding documents of cyber-capitalism.footnote7 While dedicated to war, the new research laboratories provided spaces for intellectual inquiry, allowing for free-wheeling, interdisciplinary and inter-institutional research and large-scale collaborations. They shifted the trajectory of technological development, from incidental and piecemeal results of individual creativity and practical tinkering—as exemplified by someone like Nikola Tesla—to institutions designed to transform social practice. These techno-scientific projects would move beyond the conquest of nature—the dream of the early-modern scientific revolution—to aim at its reconstitution: the reorganization of social life at a higher level of abstraction. Thus if capitalist modernity was more abstract than the various feudal and customary societies it displaced, the cybernetic transformation would take this to another stage. The ‘leveling domination of abstraction’, to use Adorno and Horkheimer’s phrase, involved levelling in two senses: leveling as in flattening—such as the colonial destruction of deep social relations and place-based practices—and levelling as in adding new layers, with the reconstitution of social relations by more abstracted practices.footnote8

With the atom-bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the us announced its arrival as the supreme superpower of the capitalist world. But the landscape it confronted was one of global rebellion and upheaval. On the day of Emperor Hirohito’s unconditional surrender, the August Revolution began in Vietnam, with Viet Minh taking over Hanoi, beginning a struggle for independence that would take thirty years of war. Two weeks later, Indonesia declared independence, after three centuries of Dutch domination; within a month, Gandhi and Nehru were demanding the removal of all British troops from India. Anti-colonial movements fired up, attacking the older imperial-industrial powers and asserting their sovereignty just as power was being abstracted away from direct control of territory. These struggles—against older empires and us hegemony alike—were not cybernetic in essence, but were soon to be confronted with this more abstract layer, for us counterinsurgencies served as a crucible for developing techniques of communication and control. The collapse of older orders of colonialism was matched by attempts to weave a more abstracted form of imperial power atop this rapidly changing global order.

Cybernetic technologies were rapidly deployed against perceived enemies abroad, above all the ussr and Third World anti-colonial movements, as well as workers and radicals in the rich world. Yet the abstracting power of the techno-sciences was not Washington’s to keep. In 1949 the Soviet Union detonated an atomic weapon. In the same year, the Chinese Communist Party emerged victorious from the bloody civil war; within fifteen years, Beijing had acquired nuclear weapons of its own. Not long after it would begin a calamity-ridden quest for wealth and power that has been triumphant, with the country assuming the position of an aggressively nationalist world power. Today, it is in the grip of what I have called ‘cybernetic capitalism with Chinese characteristics’, as an active and unpredictable struggle for hegemony over this more abstract stratum gets underway.footnote9

Cybernetics ascendant

Emerging from the nexus of military-imperialist, capitalist and techno-scientific intellectual forces entangled at the summit of the us state, the cyber-capitalist sector has retained its elite ‘steersman’ character even as it has penetrated the wider economy, colonizing and reconstituting less-abstract forms. Analytically, it can be conceived as a thin layer, spread unevenly across the capitalist world-system, overlaying older patterns of social practice—Fordist production, the print media, subsistence farming, informal labour—transforming but not necessarily eradicating them. Thus, for example, while the postal service as a means of communication was overlaid by increasingly higher forms of abstraction—the telegram, telephone, moving image, radio, tv, teletext, fax, internet, virtual reality, artificial intelligence, gps—it persisted; today, however, while it can still convey hand-written letters, it does so through systems thoroughly reorganized by computer-controlled logistics. Initially after 1945 the older forms remained preponderant; cybernetic capitalism could co-exist with other modes—indigenous ways of being, traditional beliefs like the universalizing religions, modern forms such as the post-Westphalian nation-state. Moving forward to the present, it is no longer emergent, but the globally dominant social formation, with the older forms in part reconstituted on a more abstract level, with tensions, conflicts and contradictions appearing between the various levels.

Many aspects of this transformation are discussed under the rubric of ‘neoliberalism’. No doubt the brutal drive to put profit über alles has had devastating ramifications for society, subjectivity and the planet’s ecology; yet the focus on production and exchange should not occlude other aspects, such as communication, inquiry, organization and technology. Neoliberal transformations are underpinned by cybernetic changes that laid the foundations for a global market to operate, via instantaneous communication and rationalized logistics. The intellectual fathers of the neoliberal doctrine were quick to grasp this. Following the lead of neo-Malthusian ecologist Garrett Hardin, Hayek celebrated the ‘mutual adjustments’ of cybernetics’ regulatory function as an instantiation of the invisible hand: ‘This foundation of modern civilization was first understood by Adam Smith in terms of the operation of a feedback mechanism by which he anticipated what we now know as cybernetics.’footnote10 At the same time, this view failed to grasp the radical discontinuity of cybernetic capitalism. Plainly Smith, or Hayek for that matter, couldn’t imagine the vast amount of surveillance data amassed behind an individual Facebook profile, enabling the automation of real-time psycho- and geo-targeted advertisements to ‘nudge’ consumer behaviour. If this was not the liberal market utopia they had in mind, that is indeed the point: the rupture represented by cyber-capitalism means that it was previously unthinkable.

Wiener’s claim about the new age of cybernetic communication and control proved prophetic. Networked computing-machines have spread intensively and extensively in world-historic ways, their abstraction processes cutting into the very basis of human sociality, hacking away at more grounded forms of existence. Expanding outward and downward from the military-industrial complex, driven by the quest for new markets, cyber-capitalism now operates through a material ensemble of social practices, meanings and technological apparatuses—a vast, globe-spanning conglomerate of multiple layers of systems and standards, machines and management, labour and legalities, commodities and communications, ideologies and interoperability, products and protocols. From this cybernetic layer come multiple feedback loops that reorganize less-abstract levels of social existence, undermining and unsettling taken-for-granted ways of being and doing in the world, overlaying them with technologically mediated, power-concentrating, inequality-intensifying, labour-automating, financially speculative, energy-intensive forms that are above all profoundly abstract.footnote11

One aspect of continuity has been the relation of cyber-capitalism to the summit of the military-industrial complex. The reference may evoke images of olive-drab generals and Eisenhower’s famous speech, yet the material-power structure it denotes has not gone away but rather extended its tentacles deep into everyday life and globalized across the world. A comprehensive update today would rebrand it as the national-security, techno-financial, entertainment-surveillance complex. The invention of the internet, a collaboration between darpa, the Pentagon’s r & d department, corporations like ibm, think-tanks like rand and highly trained techno-scientists at mit, Stanford and elsewhere, is a case in point. Aerospace and weapons companies like Raytheon, Boeing and Lockheed Martin have been integral to cyber-capitalism’s success. The tech giants remain tightly linked to the military-industrial complex.footnote12

Capitalist logic

Contrary to techno-feudal interpretations, the cyber-tech sector is unmistakably capitalist, driven by competition, investment and innovation, and subject to speculative bubbles and booms unheard of under feudalism—if also characterized by supposedly non-capitalist but thoroughly familiar practices like monopolization, market rigging, preferential nationalism and proximity to the military-industrial complex; while its feverish growth speaks also of the $9 trillion of financial assets magicked up by the Federal Reserve over the past decade. At the same time, the cluster of giant cyber corporations that currently occupy the pinnacle of market capitalization—Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Facebook, Tesla—have genuinely novel features whose importance is missed by Morozov’s characterization of them as doing what capitalist firms have always done. Each has its own set of strategically diversified operations, ranging from social-media advertising to business logistics, video-games to semi-conductor manufacturing, with distinctive cultures and growth paths. All are subject to the high degree of volatility and ‘creative destruction’ that characterizes the sector; not that long ago, aol, MySpace and Yahoo would have loomed large. Focusing on Alphabet, the sprawling conglomerate formerly known as Google: can the concept of cyber-capitalism provide a more compelling explanation for its rise than Morozov’s avowedly ‘messy’ notion of traditional, appropriative-exploitative capitalism?

Google’s origins in the mid-90s lie in the same nexus of summit institutions that gave birth to cyber-capitalism in 1945. Already by 1993, the us intelligence community, or ‘ic’ as it referred to itself in the internal documents of the time—principally the cia and nsa; the dia may have been operating independently—was seeking to commission research into systems for tracking the data produced by the spread of personal computers, primitive email systems and the nascent worldwide web. darpa, nasa and the National Science Foundation funded research by Stanford’s Department of Computer Science into managing large data systems, including early work by graduate students Sergey Brin and Larry Page that led to the development of their web crawler and page-ranking algorithm in 1996. The pair registered the google.com domain name in September 1997. The start-up caught the updraft of the first dot.com bubble, as the dollar strengthened and hot capital fled the East Asian financial crisis. From $1 million in 1998, Google’s capitalization ballooned to $25 million a year later. But there was a glaring absence of profits. The ‘search-results commodity’ said to signal that Google was a normal firm couldn’t actually pay the rent. After the 2000 dot.com crash, investor demands for proof of profitability led the company to head its search-results pages with targeted advertising spots, linked to search queries—abstracting and marketing the data produced by would-be consumers. It was on this basis that Google’s ipo in 2004 valued the company at $85 million.

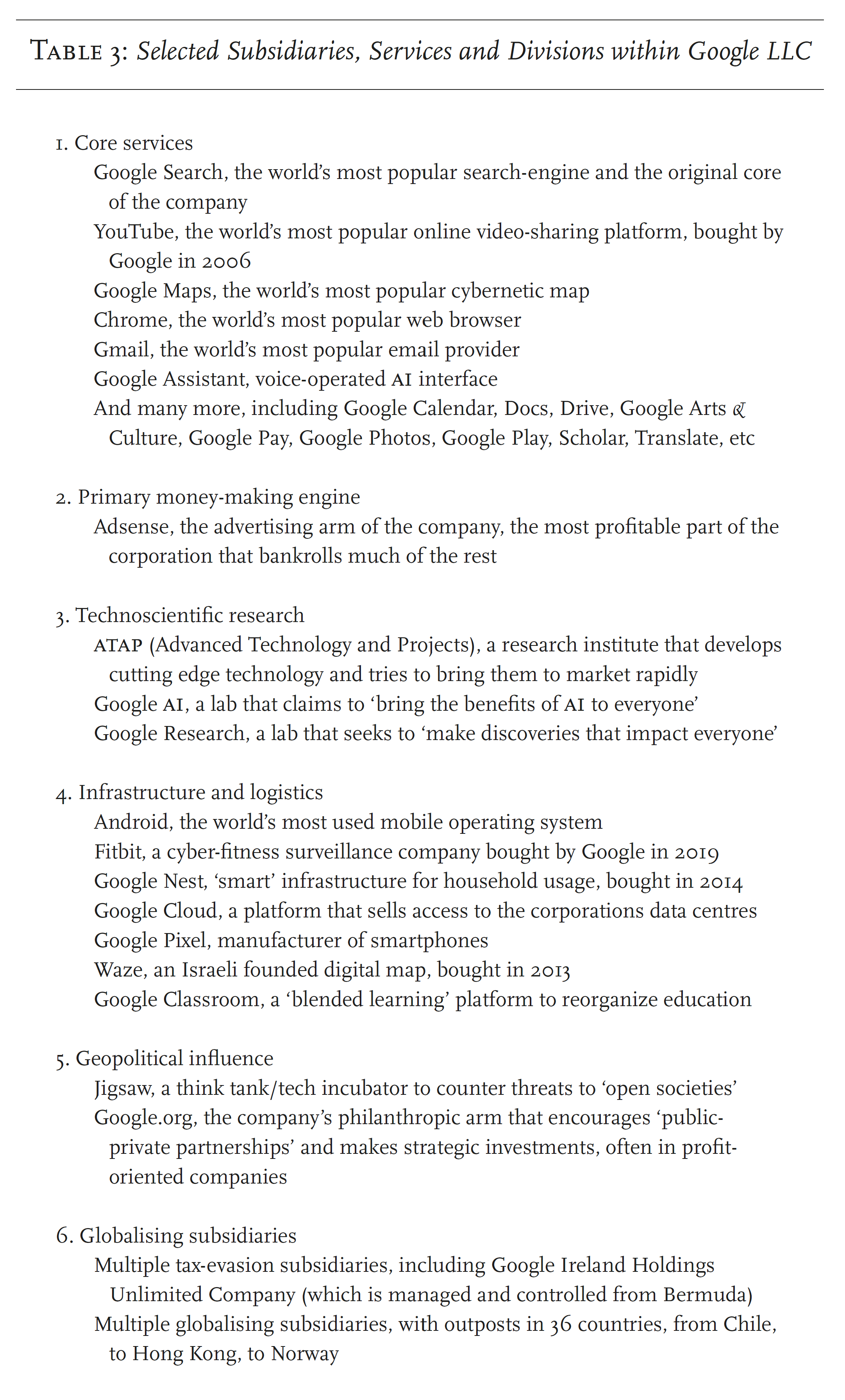

There is nothing new about selling ads, as many have noted. But Google’s way of doing it—via automated, surveilling, networked computing-machines—operates on a higher level of abstraction to those which preceded it. Google’s strategy has been to leverage its dominance in data-driven advertising and its techno-scientific power to expand its hold over the ‘global information infrastructure’, to use Al Gore’s messianic expression. The build-out of digital infrastructures aims at an ever-widening ‘colonization of everyday life by information processing’, drawing more grounded practices into the circuits of cyber-capital.footnote13 One of Google’s first moves was to expand into communications with the launch of its email system, Gmail, in 2004. The following year it acquired the Android mobile-device operating system, which has since gone on to dominate the global smartphone market, with parallels to the infrastructural power that Microsoft’s operating system gained over desktop computers, a market it still dominates by 75 per cent. In 2005 it snapped up YouTube, currently the world’s second most-visited website, after Google Search.

Google Maps was also unveiled in 2005, and acquisition of Keyhole, a geo-spatial mapping-data service part-financed by the cia’s venture-capital arm, In-Q-Tel, and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, spurred the development of Google Earth, using nasa satellite data. Much of the gig economy and the real-estate sector—every Uber driver’s turn-by-turn navigation, every short-term rental on Airbnb—would soon be mediated through Google’s cyber-cartographic infrastructure. In 2008, following Amazon’s lead, the company launched Google Cloud, renting out the massive computing power of their data-service centres to the capitalist economy as a whole; providing not only big-data storage but analytics, machine-learning technologies, workflow-management techniques and cybersecurity services. This approach shot Google into the ranks of the top ten global companies in 2013, with a valuation of $238 billion (Microsoft had been listed there since 1997, Apple since 2009). Needless to say, this was not the trajectory of a typical ad-marketing company. Along with its peers, Google’s build-out of communication-information infrastructure has radically expanded the digital realm, creating exponential quantities of data to manage—and therefore to command. It is propelled not only by the capitalist drive for profit, but also by an intrinsic logic of cybernetic expansion.

Cyber-finance

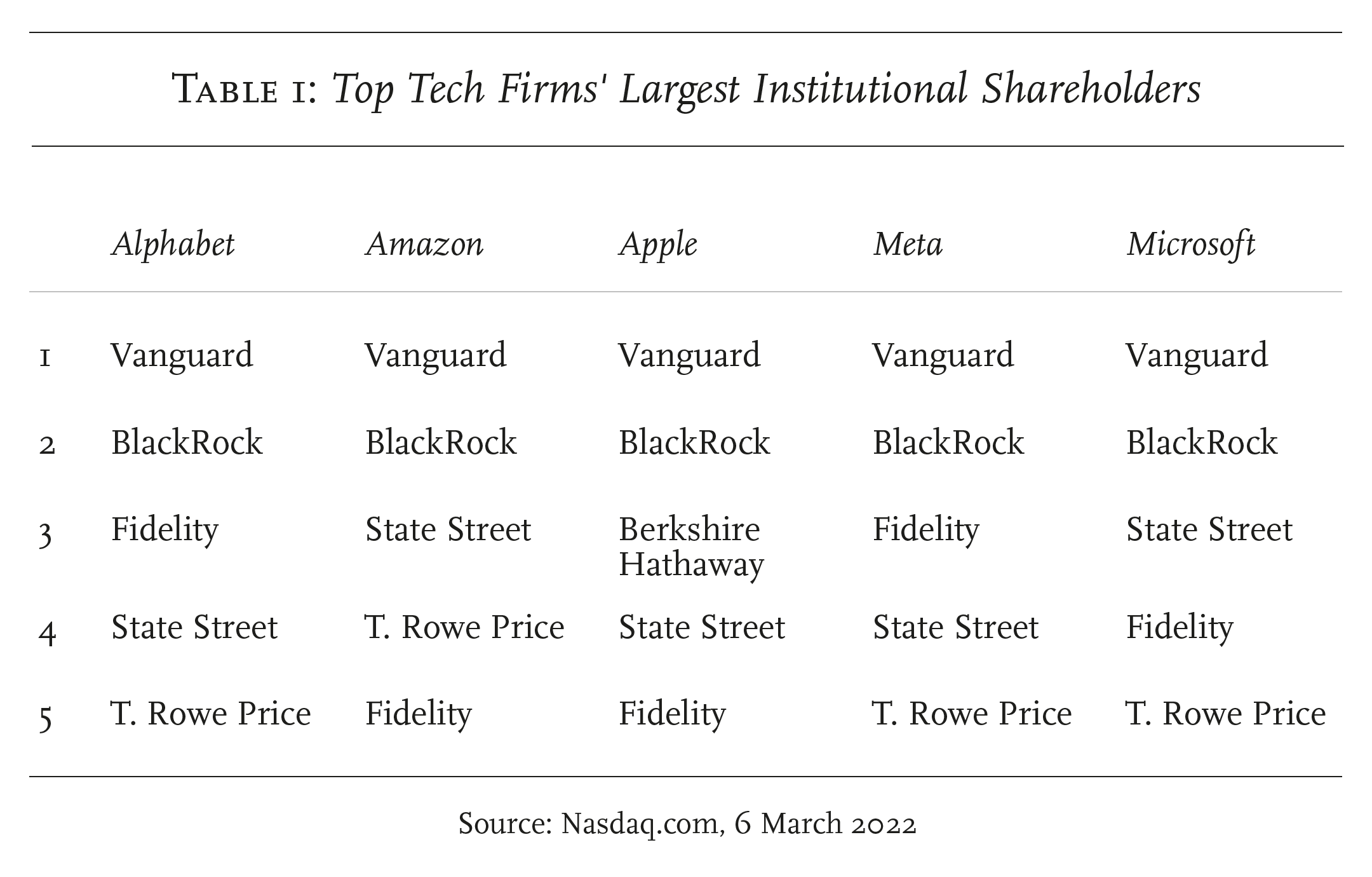

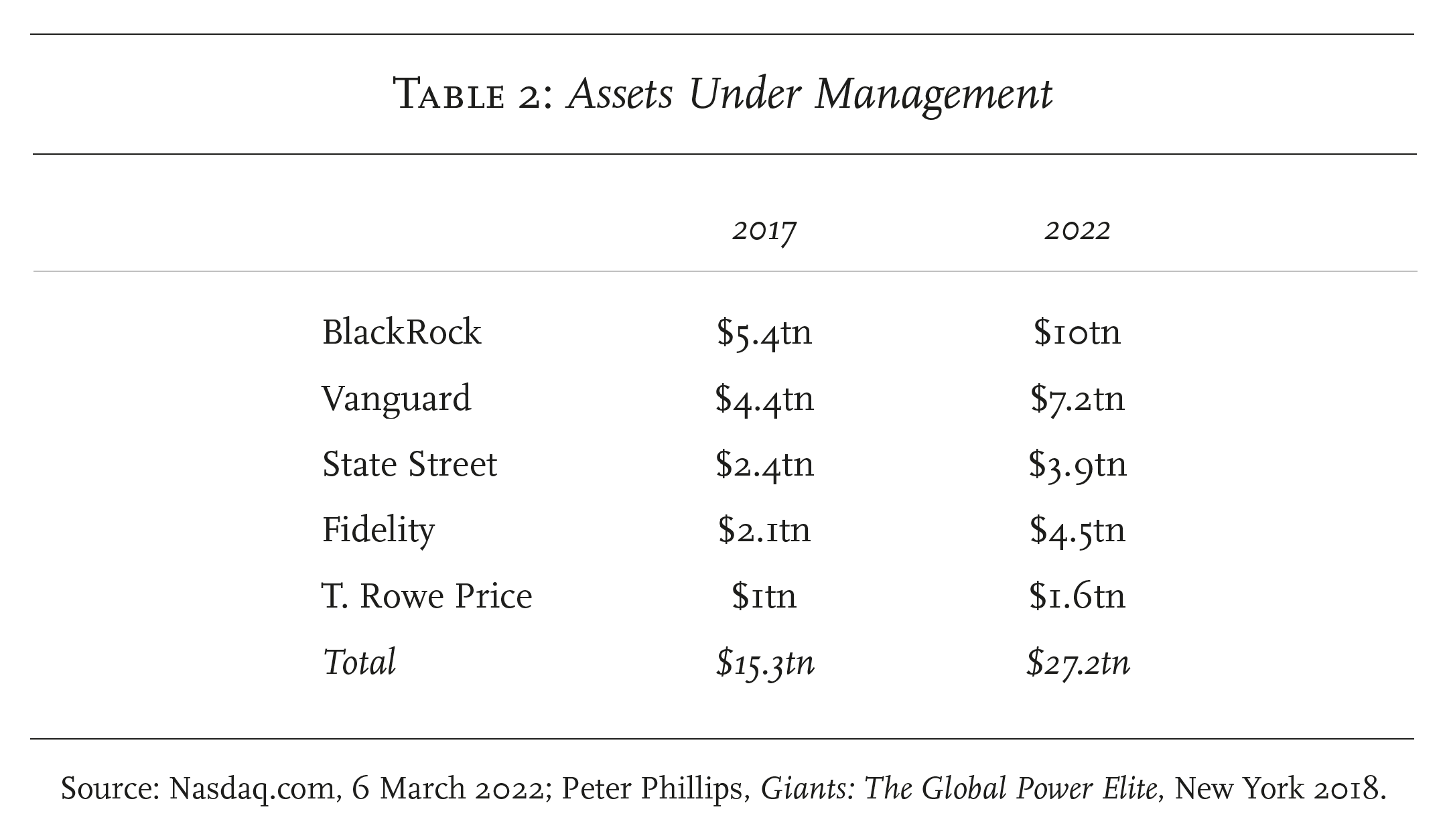

Behind the rise of the tech titans lay the inflated fortunes of the financial sector (Table 1). The gargantuan asset-management firms Vanguard Group and BlackRock are the largest institutional investors for the five top companies, followed by State Street, Fidelity and T. Rowe Price. These firms themselves have been thoroughly remade by cybernetics. BlackRock, for example, attributes much of its success to its big-data system, Aladdin (Asset, Liability and Debt and Derivative Investment Network), which manages huge investment portfolios not only for BlackRock but for its rivals Vanguard and State Street, as well as Alphabet, Apple, Microsoft, the big insurance companies and Japan’s state pension fund, the largest in the world.footnote14 Through Aladdin, BlackRock thus controls a key component of the financial sector’s digital infrastructure. Investment itself has been radically reorganized by cybernetic processes, which play a central role in the control and allocation of capital. As Cédric Durand suggests in Fictitious Capital, this fusion of financial power and technoscientific mastery brings finance itself to a more abstract level, as a key component of cyber-capitalism.footnote15

The asset-management firms were prime beneficiaries of the money-supply revolution spearheaded by the Fed to refloat the financial sector after 2009 (Table 2). The sums they command have nearly doubled over the past five years—matched by the inflation of tech stock. In 2015, Google made the surprise announcement that it would be reorganized into a holding-company, Alphabet, Inc. The reshuffle was lavishly rewarded by Wall Street, stocks climbing by another $200 billion in just six months, although the core business remained exactly the same, in the context of a soaring Nasdaq.footnote16 Thereafter Google’s value leapt to $727bn in 2017, $922bn in 2019, $1.1tn in 2020 and $1.9tn in 2021, after the bipartisan giveaways of the pandemic. Taken together, Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Tesla and Facebook currently have a collective market capitalization of over $9.5 trillion. By way of comparison, this is just shy of the combined gdps of Germany, the uk and India. This speculative gamble is the largest financial bubble ever to have been inflated. It is also a measure of the exponential increase in inequality over the last half century, the curve getting rapidly steeper with the Covid pandemic, used by the American governing class for a massive transfer of wealth from poor to rich. The bubble itself is a powerful driver of more extreme inequality, an increasingly abstract feedback loop ravaging the social and ecological fabric of the planet.

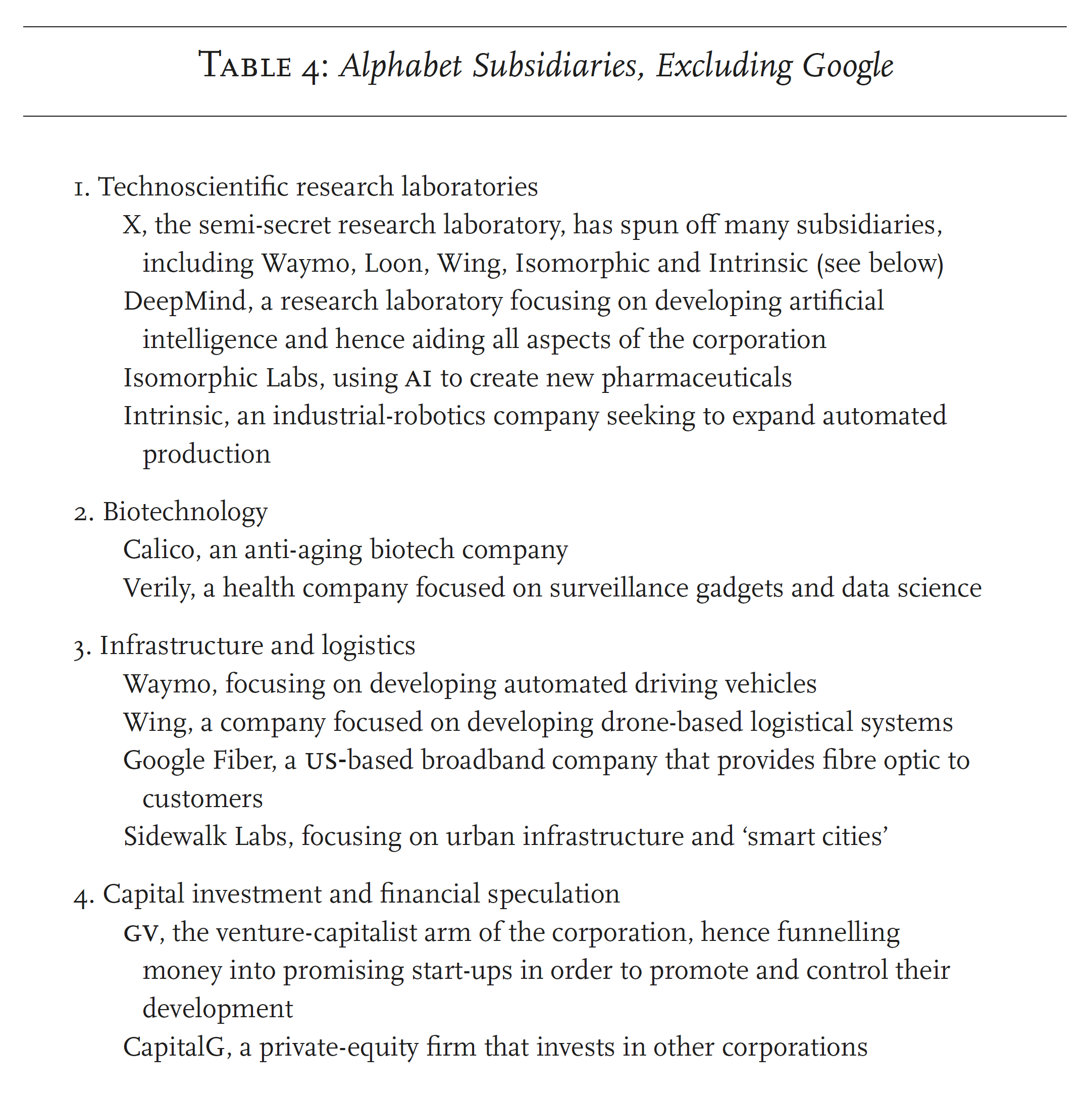

A closer look at Alphabet/Google suggests that the 2015 restructuring—under which Google became a wholly owned and internally managed subsidiary of Alphabet—positioned the latter somewhere between a private-equity firm, like Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, and a gigantic conglomerate, like General Electric under Jack Welch, mixing subsidiaries, outsourcing and financial speculation. The internal landscape of the company is fluid and fast-changing, with subsidiaries acquired, spun off, reorganized or shut down at a breakneck rate. There are a plethora of separate branches, which can be analysed under five headings (Table 3, overleaf). Beyond its most famous services—Search, Maps, YouTube—and the money-making engine of online advertisements, Google devotes significant attention to techno-scientific research in infrastructure and logistics. Alphabet’s other subsidiaries follow the same pattern (Table 4, overleaf). Alphabet spent nearly $32 billion on techno-scientific research in 2021—around a fifth of the Federal government’s annual research budget across all departments, including Defense. Collectively, the tech-titans control levels of research spending that are beyond state-like, going into superpower territory: over $156 billion on research in a single year.footnote17

In addition to digital infrastructure, Alphabet is keenly focused on gaining more logistical power. One example is its subsidiary Waymo, an autonomous-driving tech-company that began in the StreetView component of Google Maps and was then spun out. One point about cybernetic vehicles is that, for a computer to drive, it needs to extract, process and transmit immense amounts of data: exact calculations are complex, but all experts seem to agree that the quantity is truly massive. Processing such vast quantities of data will demand much more electricity; the communications-technology sector is already on track to consume over half the world’s electricity by 2030.footnote18 Another Alphabet subsidiary, Wing, focuses on drone systems, aiming to build commercial-delivery services on the basis of military-industrial research.

Biotech, robotics, artificial intelligence, logistics and urban infrastructure: the sprawling diversification of Alphabet—in common with that of the other tech giants—shows that the conglomerate is much more than a narrow indexer of web pages or seller of advertisements. Looking deeper, this is not narrowly conceived surveillance or same-old capitalism with added data, but rather an expansionist new sector whose growing empire is enabled by cybernetics, by the techno-scientific abstractions of intellectually trained workers.

Cybernetic colonization typically takes grounded practices and remakes them on more abstract levels. An example at the most intimate level is Alphabet’s recent acquisition of FitBit. Like other ‘wearable technology’, FitBit devices use biometric surveillance to extract data from the body in order to provide biofeedback to the wearer via Google’s servers, using the techniques of data mining to pry into intimate aspects of our being—heart beats, sleep patterns, mood fluctuations, steps taken where and when. These technologies effectively treat people as ‘libidinal strip mines’, as traces of their embodied existence are drawn away to the most abstract levels of technological disembodiment.footnote19 Parallel processes occur on a larger scale with technologies like Google Nest or Amazon Ring. There have never been more compelling arguments to reduce inequality, to consume less, to live less energy-intensive lives, yet the tech-titans dedicate tremendous resources to encourage an increase in the production and consumption of wasteful, energy-intensive gadgets—‘spending the money we earn by working too hard and too long on commodities and commodified experiences, to replace the more diverse, enriching and lasting satisfactions we have sacrificed through over-work and over-production.’footnote20

The present conjuncture cannot be adequately explained by theories of a new digital feudalism, nor as merely more of the same. Via disembodied communication networks of computing-machines, cyber-capitalism’s grip on the means of abstraction has allowed for tremendous intensification in the automation of production, financial speculation, bureaucratic organization, hyper-consumption, all of which are put into the service of capitalist accumulation and the projection of social control. Flowing from this is a whole range of drastic transformations across all domains of life, both on the level of social practice—ecological, economic, political and cultural—but also on a deeper ontological level, with a remaking and unsettling of the human condition and the natural world. The remaking of the life-world is not in itself a novelty for capitalism; indeed, it has done this several times over. Electrification, the invention of the internal-combustion engine and motorized flight revolutionized the advanced-capitalist world from the 1890s; planetary urbanization has perhaps changed it even more. But comparison of the current transformation with the second industrial revolution only underlines the importance of grasping what is unique to today. The abstraction of communication and information is transforming the life-world outside of any political-democratic decision-making or accountability, driven by the logic of cyber-capital itself.