The opening room of lux: New Wave of Contemporary Art, an exhibition of technological wonders curated by Jiyoon Lee with the collaboration of the new-media arts organization fact, is symptomatic of much of what follows. Suspended from the ceiling are a group of digital flowers by iart Studio, the petals of which are carried on curved widescreen monitors of the kind often used by gamers. They rapidly change colour to suggest budding, blooming, decay and death. The labyrinthine exhibition space—the basement levels of 180 The Strand, a brutalist office complex—plunges the viewer into a profound darkness out of which loom naked concrete walls. The heavy blood-red curtains that must be lifted to access most of the works lend the exhibition promenade a faintly Grand Guignol air, and indeed various of the curtains are pushed aside to reveal bodily hybrids which teeter between fascinating attraction and horror.footnote1

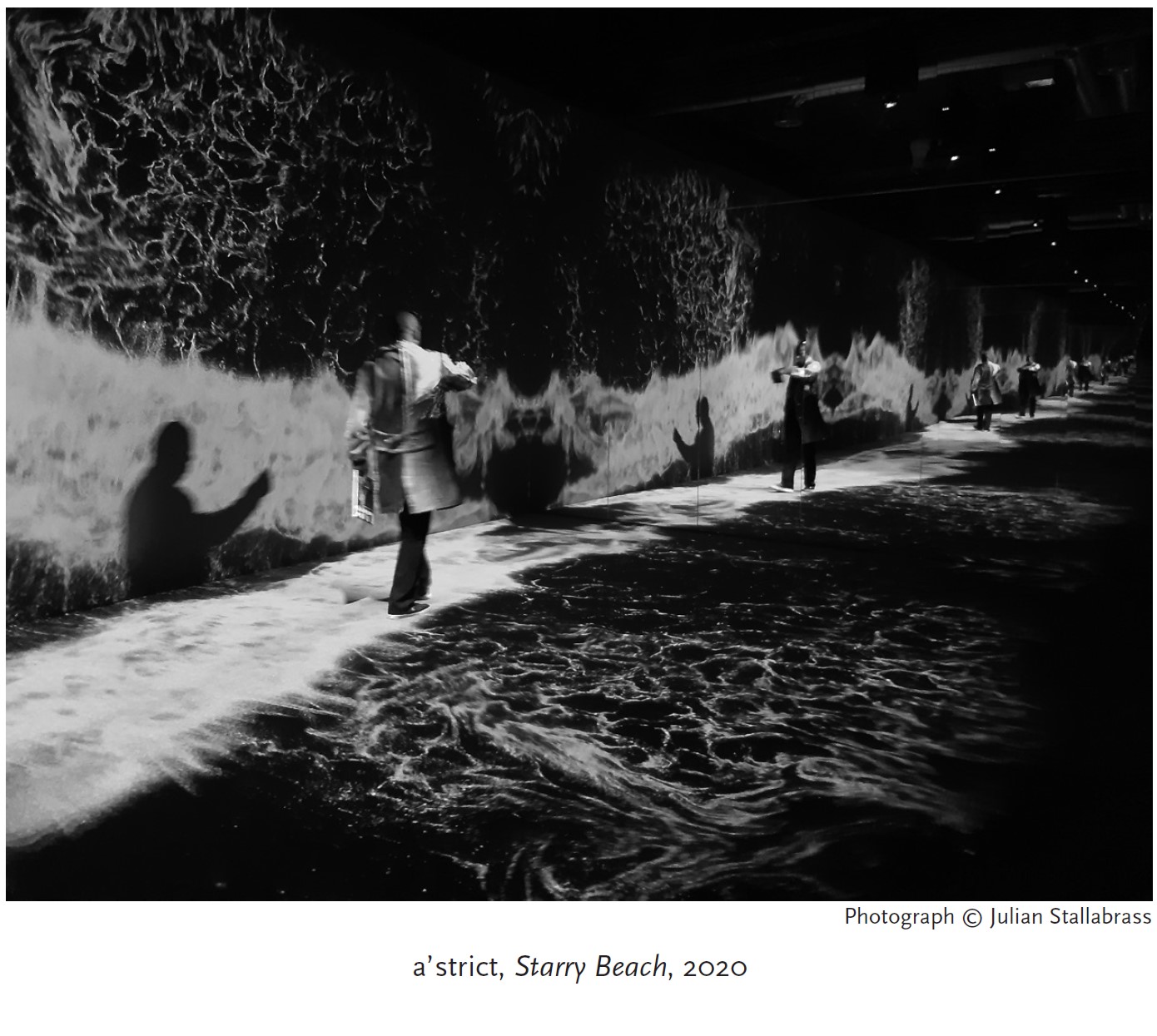

One signature work (used on the exhibition posters, and picked up in its title) is a’strict’s Starry Beach, an impressive projection which convincingly animates breaking waves as seen under a night sky. The projection spills from the wall to the carpeted floor as the waves wash over the viewer’s feet. While the room is small and narrow, since its side walls are mirrored the waves seem to stretch to infinity, and the viewers are multiplied along the greatly elongated shore. As in the exhibition as a whole, the interplay of light and dark is a theme of this work, the waves made up of tiny points of glistening light which provide the only illumination; viewers can step into them, so that these points dance across their bodies.

The mirrored illusion of vastness contributes to what is a textbook example of the Burkean sublime: the wide, stormy beach at night is experienced safely boxed into an indoor space without any of the inconveniences or dangers of exposure to the elements. At the same time, the mirrors pitch viewers into a heightened state of imagistic self-awareness (if, since so many of them wield phones, they weren’t already there), and open up opportunities for playing with selfies and other forms of social-media display. It is part of a by now familiar effect in which works of art are made, more or less openly, as honey-traps for social-media users, and in which the use of mirrors is the most obvious move. It has helped to boost a few veteran artists who have long used mirrors—such as Yayoi Kusama and Michelangelo Pistoletto—to new heights of fame. It also suggests that the sublime may not bear only on grand and potentially dangerous natural forces but also on what are for the user the incalculable manipulations of the social-media monopolies.

This double mirror trick is used again and again throughout lux, multiplying the effect of large-screen displays and projections, while shrinking the viewer. Elsewhere I have written about the effects of the data sublime, for instance as seen in large-scale museum photography by Andreas Gursky, Jeff Wall and many others that immerse the viewer in more points of information than they can make sense of, in an aesthetic of disorientation and loss of cognitive mapping. This sublime effect—loosely, of the mathematical in Kant’s terms—is accompanied in other works by a dynamic sublime in which the rapidity of data flows, rather than—or as well as—their extent, is also meant to overwhelm the viewer.

A few years ago, Google applied its image-identification software, trained on enormous datasets, to interpret visual noise: it ‘read’ the most commonly photographed objects into random pixels, creating ‘dream images’ in which for example the eyes and fur of a billion pet pictures were generated across surreal landscapes. Some of the lux displays use ai processing to pursue this new form of the data sublime: one of calculation or computation. Machine-generated works are nothing new, of course: we may think of Harold Cohen who from the early 1970s wrote programmes that allowed computers to draw their own creations, and showed the process operating live, using plotting machines. What is new here, and undeniably impressive, is the scale and speed of this processing, the vast datasets on which it draws, and the hypnotic vision of an inhuman intelligence playing with human cultural techniques and material. While it would be fascinating to see such processes live, what we are actually presented with in lux is short-looped videos of already rendered and edited sequences.

For instance, Cao Yuxi in a work called Shan Shui Paintings by ai renders on a dramatic installation of curved screens in a once-more mirrored space a mesmerizing liquid flow in which East Asian ink-painting landscapes are continually evoked and erased, never reaching a fully realized form. Each tiny pixel appears as part of a radiant dust carried in the ever-restless fluid. This dynamic and computational sublime, drawing from online image data, gives an oneiric vision of painterly creation and its transient life.

In a very different display, Refik Anadol applies ai processes to a dataset of Italian Renaissance art to create projections in a tall, narrow room, once again mirrored on wall and ceiling, into which the viewer can wander. This work cycles through distorted and rapidly changing buildings, landscapes and especially portraits which do briefly resolve into familiar-looking images. Yet the monstrous is only ever a step away as faces erupt into bulbous forms that appear as tumours, or are overloaded with cobweb lines, amid the continual ebb and flow of bright spheres that look like broken-up polystyrene. The whole gives the impression of an endlessly looping fever dream of a Renaissance connoisseur. If the effect is once again hypnotic—the viewer is held in the sublime of a vision of a superior generator of painterly form—it is because the work opens up a glimpse of a future in which the traces or indeed ruins of human creation are reworked forever by inhuman intelligences.

The rapidly transforming hybrids of both these ai works point to another common theme in lux, which is seen in works that are merely animated. In Universal Everything’s The Transfiguration, a stocky humanoid figure, reminiscent in its gait of Shrek and many a gaming avatar, marches steadily and apparently endlessly while remaining centre-screen. As it goes, the figure constantly changes from lava to stone to wood to foliage to fire to smoke and so on, with the attendant sound effects. In another, by the dancer Cecilia Bengolea, a digital rendering of her body is subjected to similar changes, although here more evocative of a sexually charged cyborg. She acquires a skin of coloured glass, and morphs through a bestiary of imaginary creatures. As in much contemporary painting, especially in street art, and of course in advertising, the effects of a mild and commercially friendly Surrealism are felt (of ‘Avida Dollars’ in Breton’s play on Dalí’s name). In another animation, Je Baak renders amusement-park rides such as Ferris wheels and roller coasters into continually mutating sculptural forms which interconnect, as pistons thump into apertures, although they continually seem to be on the brink of collision or collapse. This is an update of the Dada interest in the masturbatory mechanism, as pursued by Duchamp and Picabia: it was then a critical take on the mechanized slaughter of the Great War, and the perversely ‘rational’ instrumentalism that lay behind it. Now it is harder to say: perhaps the spectres of Donna Haraway’s cyborgs are hinted at here, but many of these works seem like a sleek celebration of the fragmented and precarious selves of social media, serfs of the algorithm, under continual pressure to fabricate their brands which are endlessly tested against feedback.

That serfdom is equally seen in the works themselves, which (with a few exceptions such as a’strict’s Morando, an X-rayed peony going through its life cycle in three minutes) are sharp-elbowed pieces jostling for attention, with their striking visual qualities and loud, portentous soundtracks which rumble through visitors’ bodies. In this striving to attract eyeballs, many of them simultaneously play with utopia and dystopia, heaven and hell, transcendence and apocalypse.

In the interpretative panels on the walls, and in the special issue of fact magazine that serves in part as a catalogue, the utopian clearly wins out. The show is part-sponsored by lg, which provided the gaming screens mentioned earlier and indeed commissioned iart Studio’s work. The interpretation is marked by a technophile boosterism which, while negative effects are recognized, claims that a veritable ‘cognitive revolution’ has taken place, expanding ‘our imagination and means of communicating’. The texts in fact convey a sweetly naïve image of young creatives bravely transgressing media boundaries and collaborating with their peers and corporations alike. In a conversation with Es Devlin, the renowned curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, who knows the very long history of such engagements better than most, pretends to be amazed. pr-manufactured origin-stories support the work, just as, in the art market as a whole, they do a wide range of products, including those in the most conventional media. Amid the technological glitter, the implicit ideology of the exhibition and its supporting literature is conservative. The disabling forms of the sublime, which tend to reduce the viewer to an awed passivity before the natural hierarchy, suggest as much, as do the adverts for suvs and other luxury goods that open the catalogue.

A few works offer a more explicit politics. Julianknxx’s Black Corporeal (Breathe), an immersive video installation showing Black gospel singers who undergo strange transformations against a polished church space, heightens the volume and distinctiveness of their singing and breathing. This work has an affinity with a video projection, Oh, The Wind, by Theaster Gates, recently shown at White Cube, in which the artist breathes heavily as he preaches and sings, stumbling through a long improvised performance. In both works, singing is an emanation of resistance, and the highlighting of breath points to its deadly denial by the police. Both works are high-resolution and large scale, yet Julianknxx’s work contains immaculately dressed and lit figures against the ceremonial propaganda of church architecture. Gates’s figure looks indigent, and shuffles about in a vast industrial ruin: here resolution is turned into a detailed description of dereliction, suggesting the social depths out of which resistance echoes.

Another is Hito Steyerl’s installation, This is the Future, staged in a narrow space which is intended to press viewers uncomfortably up against a low-resolution video projection which is thus difficult to take in as a whole. This work explicitly evokes ecological collapse and the uncertain means somehow used to ensure the survival of a garden hidden in the future. Steyerl is an assured juggler of the uncanny, digital glitches, humour and artistic persona who gives viewers a calculatedly incongruous and estranging take on the perilous impetus of techno-capital. In lux, though, her work is but one distinct episode in the digital Wunderkammer, and is folded into the sublime whole as the viewer transits uncertainly though the darkness and lifts another curtain to reveal the next marvel. The danger for the whole exhibition, though, is that the sublime and the uncanny so insistently propagated fail to take a hold on the viewer—that they fall flat in inadvertent comedy and kitsch. Steyerl is alone here in courting that effect; for the wide-eyed corporate whizz kids, it must remain anathema.