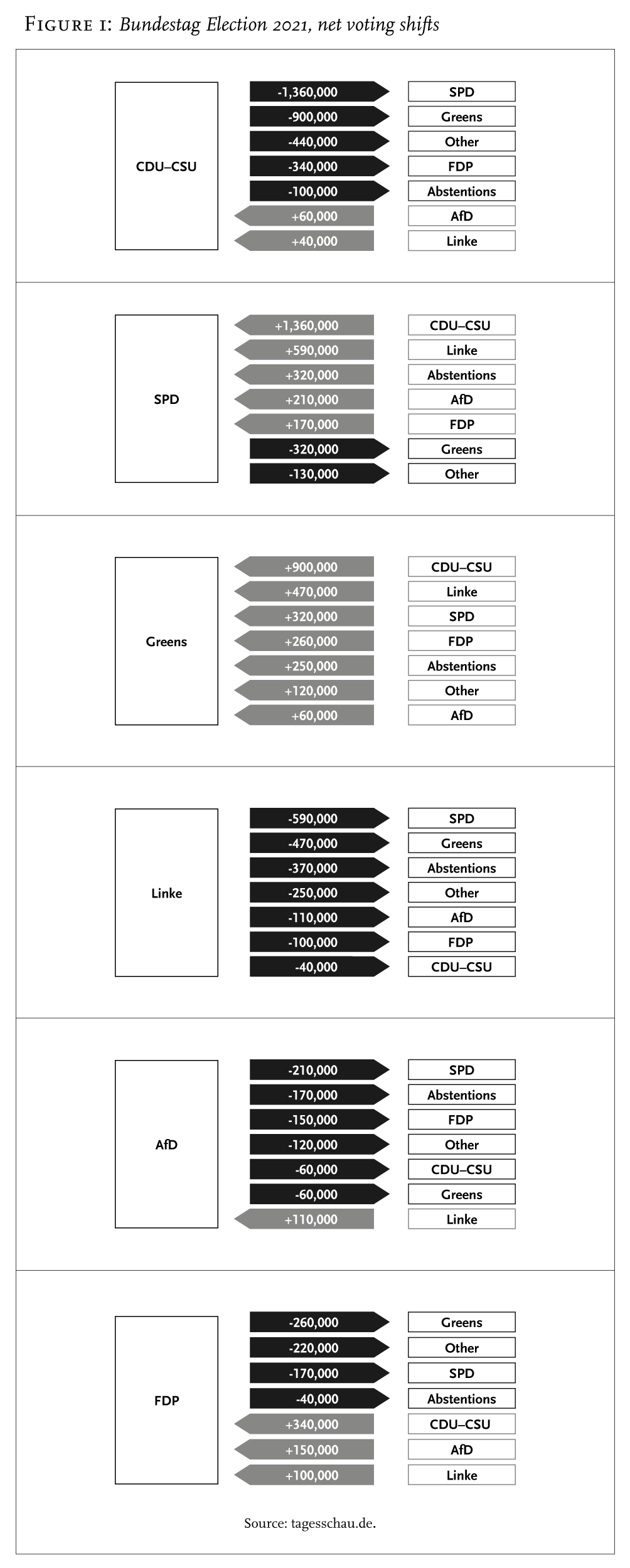

Among the many astonishing upshots of the 2021 German election, the near-death of the Linkspartei stands out. It lost over 2 million votes, falling to 4.9 per cent, barely half the 9.2 per cent it received in 2017. That it remains in the Bundestag at all is because it won three constituencies directly, two in (East) Berlin and one in Leipzig, meaning that the usual 5 per cent threshold does not apply. Still, the only remaining party of the German Left, heavily divided, is about to drift into insignificance. The depth of its crisis is indicated by the fact that it won only 8 per cent of the vote among under-25s, close to the afd which ranked bottom among this cohort, on 7 per cent. Add to this that the Linkspartei was supported by only 3 per cent of those with the lowest educational qualification (Hauptschule), while it won 6 per cent, above its national average, among voters with Abitur or a university degree. And most devastating perhaps: among workers the spd won 28 per cent, the cdu/csu 23 per cent, the afd 16 per cent, and the Linkspartei—5 per cent!

1

The demise of the Left all of a sudden simplified a picture that had looked unprecedently disorderly before the vote. Now there was no possibility anymore of a Red–Green–Red (r2g) government coalition, much to the relief, one can be sure, of the leaders of both the spd and the Greens. Only two possible coalitions remained, each including the Greens and the fdp. One would be led by the spd under Olaf Scholz, on 25.7 per cent—up by 2 million votes, from 20.5 per cent four years ago. The other, the Black–Green–Yellow ‘Jamaica’ variant, would be led by Armin Laschet and the cdu–csu, which lost some 3 million votes, plunging to 24.1 per cent, after winning 32.9 per cent in 2017. A remote third possibility is another Grand Coalition, with Scholz as Chancellor and Laschet, or some other cdu figure, as Vice Chancellor. Nobody seems to be eager for this, however, not least as it conjures up memories of the disaster of last time round, in 2017, when the Merkel–Scholz pairing was finally hammered together a full six months after the election, after a first Jamaica attempt had failed.

On Election Eve, it was interesting to see just how traumatic the experience of the 2017 Jamaica negotiations had been for the political class. Apparently Merkel had lost control of the proceedings early on, and endless meetings ended in unending mess, with nobody knowing what had been decided, if anything at all. At some point the fdp, under its then and current leader Christian Lindner, became suspicious that Merkel had already reached a secret understanding with the Greens and planned to sideline the Liberals in the same way that she had marginalized them during her second term in office, from 2009 to 2013—as a result of which, the fdp had fallen below the 5 per cent threshold. Fearing a replay, Lindner, in a spectacular move that almost cost him his leadership, broke off the negotiations.

2

A short excursus on Lindner, who may be the linchpin of the next German government. Now 42 years of age, and highly instagrammable, Lindner joined the fdp as a teenager and rose fast in its ranks. He refused military service as a conscientious objector, which he later explained by his efforts, still in his teens, to launch an internet start-up firm, which however proved short-lived. Alongside studying political science at the University of Bonn, from 1999 till 2006—a doctoral thesis was started but not finished, due to his rapidly advancing political career—Lindner undertook several special military training courses to become a reserve officer in the Luftwaffe, where he was eventually promoted to Major der Reserve. He also acquired, at different points in his life, licenses as a racing driver for both cars and boats, as well as for hunting—the latter requiring, in Germany, passage of a demanding exam after following a complex curriculum of courses. In his spare time, Lindner likes driving vintage Porsches. At age 21, his start-up about to fail, Lindner was elected to the Landtag of North Rhine-Westphalia. In 2009 he became General Secretary of the fdp at the Federal level, a post from which he resigned just in time before the 2013 electoral disaster, when the fdp lost its presence in the Bundestag. A few months later, Lindner was elected its President, nobody else wanting the job. He led its return to Federal politics four years later.

3

With hindsight, it can be seen that 2017 was the beginning of Merkel’s end. Her party blamed her for its poor election result—32.9 per cent, down from 41.5 per cent in 2013—and for the rise of the afd, to 12.6 per cent; both related to the 2015 border opening. Next came devastating results in several Länder elections in the second half of 2018, in the wake of which Merkel resigned as party leader in exchange for being allowed to serve out her term as Chancellor. The deal, however, required her to cooperate in a transition arrangement with a successor as party chair and, ultimately, candidate for Chancellor in 2021. This went badly wrong. First Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer (akk), Merkel’s initial choice as cdu leader, tried to distance the party step by step from Merkel’s refugee policy, in preparation for the election. Merkel was not amused. Having forced akk to resign at the earliest opportunity, she ended up in early 2021 with Laschet as party head—the last man standing, apart from Merkel’s longtime enemy Friedrich Merz, a corporate lawyer and former party rival, whom she hates, perhaps because he impersonates her neoliberal past. By that stage the cdu had been worn threadbare by sixteen years under a leader deeply averse to anything programmatic, who systematically substituted personal loyalty for political principles. Laschet, then, had to run on a platform of both political renewal and firm allegiance to Merkel, to avoid being punished by her, as akk had been. This, as we now know, proved too much for him, as it might have for anyone.

4

In fact, things could have been even worse for the cdu. A few weeks before election day, it had been hovering at around 20 per cent in the polls, close to the Greens and well behind the spd, at 25 per cent. If in the end Laschet almost caught up with the spd, this was because of a last-minute campaign to frighten undecided voters with the prospect of an r2g coalition—a prospect Scholz could not rule out for tactical reasons. The media also played a role. At first the Greens were everybody’s darling, and backed by the vast majority of young people employed in the public-broadcasting system. Then the media dismantled both Annalena Baerbock and Laschet for various blunders during the campaign, allowing Scholz, a man without obvious Eigenschaften, to sneak into first place unnoticed. Finally, led by the faz, the press caught up to join in Laschet’s red-scare siren song.

What about Söder, the self-styled Bavarian strongman, whose political opportunism equals even Merkel’s? Compared to him, Laschet was bound to look like a born weakling, with a macho factor of exactly zero. Söder made the most of this. In the end, however, it was not enough to overcome his fundamental handicap: being from the csu, the smaller of the two so-called ‘sister parties’. Even if he now manages to push Laschet aside, a decisive test awaits him in the 2023 Bavarian Landtag elections. Whatever he does at present must help him win a decisive majority on this home turf; if he fails to do so, his career will end abruptly. Otherwise, he will certainly grab for the leadership and get it; remember that Länder first ministers can take the floor in the Bundestag any time they want, even outside the official list of speakers.

5

Returning to the present: the real winner of September 2021 was Lindner. Needed by the Greens, who are determined this time to enter government, the fdp is also vitally required by both candidates for Chancellor, Scholz and Laschet. Personally, Lindner probably preferred the latter, having in 2017 helped to negotiate Laschet’s governing coalition in the largest Land, North Rhine-Westphalia. Remembering the Jamaica disaster of that year, however, Lindner suggested within a few hours of the 2021 result that the fdp and the Greens should get together to explore whether they could agree on a joint programme and a third partner. This may portend an imminent realignment in the bourgeois centre of the German political spectrum, made possible by generational change, between long-standing political enemies, divided by different lifestyles while belonging to the same well-to-do middle class. Note that among first-time voters, the fdp and Greens won 23 and 28 per cent respectively, far outdistancing the exhausted old centre parties, as well as the ideological outcasts on the right and the left.

6

Lindner and the Greens’ option for Scholz would signal anything but a move to the left for German politics. During the campaign, Scholz presented himself as the legitimate heir to Merkel, having served under her for three-and-a-half years as Vice Chancellor and Finance Minister. He had been nominated as candidate by a party that had nobody else, a party in which many consider him to be too far to the right to be a good Social Democrat. Hardly anyone in the spd believed that Scholz could come close to winning; some even felt that the party should abstain from presenting a candidate, to avoid humiliation. Of course, nobody quite predicted the scale of Merkel’s strategic blunders in the selection of, and the transition to, her successors in party and state; taking it out with a vengeance on the party through which she had ruled for so long.

All that said, nothing is as deeply entrenched in German politics as its ‘extreme centre’ (Tariq Ali), and if the 2021 election proved anything, then it was this. This holds even though the afd, cut back from 12.6 to 10.3 per cent at the Federal level (and half its remaining vote might have gone to the cdu, had it not been for Merkel), managed to establish itself as East Germany’s regional party, replacing in this role the Linkspartei. In two Länder, Saxony and Thuringia, the afd emerged as the strongest party, at 24.6 and 24 per cent, respectively; in East Germany as a whole it scored 19.1 per cent, behind the spd at 24.2 per cent, but in front of the cdu, at 16.9 per cent. It is in the Eastern Länder that the fdp and Greens are weakest, raising the question of whether the two old centre parties, in their diminished condition, will be able to win a relevant number of Eastern afd voters back.

7

In a Scholz cabinet, which is the most likely prospect, Lindner will claim the Finance Ministry and get it (unless the Greens punish Baerbock for her dismal performance as candidate by moving her to the second row and turning for leadership to her co-president, Robert Habeck, who might have the same ambition as Lindner). With Lindner at Finance, Scholz as Chancellor can be sure that fiscal policy will remain what it was under Scholz as Finance Minister—who, when he took over in 2018, told a French journalist apparently expecting major German contributions to ‘European solidarity’ that ‘a German Finance Minister is a German Finance Minister’. In 2017, during the first Jamaica negotiations, Emmanuel Macron was reported to have said that, if Lindner made it into the next German government, he, Macron, would be dead. Four years later, that might apply more than ever.

In the first half of 2022, the—mostly ritual and symbolic—‘presidency’ of the eu Council will rotate to France, where Macron must in April win re-election. Plans have been laid for various public occasions at which Macron can display the trophies of his European pre-eminence. With a Finance Minister Lindner in Berlin—even under the Francophile Laschet, who half-seriously claims to be a descendant of Charlemagne—these will not go beyond merely cosmetic changes to the financial constitution of the eu and emu. As under Merkel, Germany under either Scholz or Laschet will do as much as is necessary for the survival of the euro, probably including the creation of more legal or semi-legal space for debt at European level; but no more than that, and negotiations over what exactly is needed will be as tough as ever.

For a realistic assessment of Germany’s eu policy in coming years, it may be useful to look at the five-year budget planning of the Federal Finance Ministry under Scholz, as agreed by the Grand Coalition. By the end of 2021, Germany will have taken on €471 billion of new debt in three years, equivalent to almost two-thirds of the Next Generation eu Recovery Fund, intended to benefit all 27 member countries over a period of seven years. To comply with the so-called debt brake in the German Constitution, Federal spending will have to fall from €548 billion to €403 billion between 2021 and 2023, so that the debt load, currently amounting to about 75 per cent of gdp, can be returned to the 60 per cent of the Maastricht Treaty. Tampering with the debt brake in the Grundgesetz is out for both Laschet and Scholz—not necessarily, however, recourse to some sort of under-the-counter fix, for which Scholz may have a more open mind than Laschet—and even more so for Lindner, who has also promised no new taxes. At the same time, enormous sums will have to be spent on renovation of the national infrastructure, already urgently needed before the pandemic. Moreover, after the floods of summer 2021, additional spending on mitigating the damage caused by climate change has become inescapable. With the Greens in government, an accelerated exit from coal will be a priority, also costly. More items could be added, the point being that there will be little if anything left for ‘Europe’ and ‘eu solidarity’, apart from, as noted, a slightly more lenient fiscal-policy and debt regime.

8

What difference would it make if the Greens’ Habeck became Finance Minister, instead of free-market, small-state Lindner? (Whether he will or not depends on the twists and turns of post-electoral ‘haggling, swapping, dickering’ (Adam Smith), and is beyond any rational prediction.) Politically it would mean that Baerbock could not be Foreign Minister, as she might have wished if she were still the Greens’ de facto leader. Habeck’s ambition would be to set up a big spending programme to fight climate change and mitigate its effects, probably financed through some vehicle outside the Federal budget so as to circumvent the debt brake. Lindner by contrast will place his hopes on private rather than public investment. Habeck would also be more inclined to allow the eu to be used as a permanent receptacle of new debt, as a first step allowing the Next Generation eu credit to be serviced and repaid after 2030 with a Next-Next Generation of additional credit, something that Scholz seems already to have promised Macron. Conflict over who gets to be Finance Minister might jeopardize the emerging alliance between the Greens and the Liberals, drag out the coalition negotiations, and even result improbably in another Grand Coalition, this time under Scholz, with a cdu Finance Minister. ‘Europe’, eu, emu and the rest will again figure only marginally, although France and Italy may have higher hopes of getting Germany to allow the eu to indebt itself in the same way as any self-respecting capitalist state these days: early and often.

Similarly bad news is to be expected, from a French perspective, on foreign and security policy. With only a little exaggeration, Baerbock may fairly be characterized as a pro-Atlanticist hawk, and the same would apply to Habeck, who during a visit to Ukraine recommended sending arms to the country for use against Russia. Baerbock and Habeck are definitely not what, in German foreign-policy circles, would still be called Gaullists; in early September, under the impress of tv reports from Kabul Airport, Baerbock happily likened herself to the American-liberal arch-interventionist, Hillary Clinton. The Greens as a party were critical of Merkel for being too accommodating of Russia and, increasingly, China, and called for Berlin to fall in line with nato demands to raise military spending to 2 per cent of gdp—that is, by no less than half. (Nothing like this is provided for in Scholz’s budget plans.) Also, while Scholz has throughout the campaign expressed support for what he calls, somewhat nebulously, ‘European sovereignty’, in terminology reminiscent of Macron, this hardly means that Germany would actively take sides with France in its conflict with Washington over issues such as aukus, the us-led ‘security partnership’ with the uk and Australia against China.

Whatever the make-up of the next German government, it will most-likely continue, or undertake to continue, to follow Merkel’s line, or non-line: trying, that is, to be on both sides of the Atlantic simultaneously, supporting American global hegemony and French European autonomy, imposing sanctions on Russia because of Ukraine while defending North Stream 2 against the us and eu, and generally attempting to make wavering to and fro look like strategic leadership. Whether, after stepping into Merkel’s big shoes, Laschet or Scholz, in conjunction with Lindner and Baerbock (or Habeck), or each other, will actually be able to replicate her complex political-dance figures will be an interesting question.