Parties, Classes, Political Cultures

Let me begin with a political fantasy. I suspect it was shared by many in the early months of 2020, after Corbyn had been replaced by Keir Starmer as Labour leader and a leaked internal report had disclosed the extent to which party officials had tried to sabotage Corbyn’s leadership—and after Starmer settled a libel claim with them, even though lawyers had advised the party had a strong case. The political fantasy went something like this. Corbyn, now a humble backbencher, seizes the initiative and leverages his considerable political capital to lead a small group of left mps out of the Parliamentary Labour Party and in doing so overcomes at a stroke the huge start-up barriers to a new political party which our firstpastthepost system imposes. In the first instance, such a breakaway would be a pole of attraction for a significant chunk of the membership who were inspired to join Labour as a result of Corbyn’s leadership (let us say, 100,000 people).

There was in this period a window of opportunity for the new party to eclipse the hapless Lib Dems as the third uk-wide party at Westminster in both number of mps—the Lib Dems have eleven—and possibly membership base. It would establish scale, and with scale comes a presence in the mass media—or at least sections of it—and esteem and credibility (not with the establishment, but with the people). It would be in a position to change the terms of the debate, shift the parameters of political conversations, just as the Corbyn leadership managed to do in a number of areas, in their best moments. In short, it would be in a position to engage in the battle for hegemony, for moral and political leadership, something which most of the Labour Party for most of its history, has been singularly unwilling to understand or contemplate. Just as importantly, the new political formation would have solved the psychological problem that bedevils small left-wing groupuscules of attracting people to a project that seems condemned to remain on the margins of public discourse. The new set-up would almost certainly have encouraged the more adventurous unions, such as Unite, under the leadership of Len McCluskey, to begin at the very least to diversify their political funding portfolio and unlock additional resources to help it grow. The result could have been electrifying in my view.

But it remained a fantasy. A collective inertia prevailed, a lack of independent initiative and agency, a lack of leadership and a failure to learn the lessons that the recent history lays before us. A veil has been cast over events by those who ought to have the greatest interest in scrutinizing what has occurred. Even the subsequent suspension of Corbyn from the plp in October 2020, on the most spurious grounds imaginable, did little to disturb the fundamental assumptions.footnote1 ‘Stay and fight’ came the cry from Labour mp John McDonnell, formerly Shadow Chancellor, as many ripped up their party cards in disgust. ‘Unite against the real enemy, the Tories’, cried the left as it appealed for Corbyn’s suspension to be rescinded, reduced to begging for re-admittance to a house that does not want it.

Nothing it seems has been learned. That the Starmer leadership is more bent on crushing the left in its own party than taking on the Tories and Liberal Democrats is barely discussed. The analogy would be the Scottish Nationalists offering the party leadership to fervent unionists. Post-Corbyn, the left bows its head and hands back the keys, as acquiescent to the status quo as the Labour Party’s tradition of Labourism has been vis-à-vis the institutions of the British state.footnote2 Clinging to Labour or orbiting around it guarantees political paralysis. Yet the absence of a debate on the strategic lessons to be learned is not something the left can afford.

Party apparatus

Corbyn’s defeat was not some swing in the pendulum of alternating power between the left and the right. Corbynism did not represent the beginnings of a revivification of the Labour Party as a progressive force. Instead it was both a last-gasp attempt to wrest the party away from the neoliberal trajectory it has been pursuing with ever greater velocity since the rise of Blair in the 1990s and a definitive historical experiment, designed to answer the burning question: can the left win inside the Labour Party? Could the party be transformed into a vehicle for socialist advance, having elected its most left-wing leader since George Lansbury in the early 1930s? The answer is now in, and it is flatly, I think, a resounding No. There is unlikely to be a next time, but even if there were, the same fundamental weakness in any such project would reappear as abundantly and as fatally as it did for the Corbyn experiment: the left cannot fight and win against the political establishment and the media establishment, still less the concentrated power of capital beyond those guardians of the social order, while it is also fighting the right-wing majority in the upper ranks of its own party.

That ‘right’—a term which we must shortly abandon for an analysis more attuned to the heterogeneity of forces at work—inside the party now inhabits the same ideological universe as the Conservatives (and the Liberal Democrats) and feels happier with the Tories in government than with Labour under a left-wing leadership. Blair articulated the collective sentiments of the Labour right very clearly during the 2015 Labour leadership campaign, after Corbyn unexpectedly became the front runner: ‘Let me make my position clear: I wouldn’t want to win on an old-fashioned leftist platform. Even if I thought it was the route to victory, I wouldn’t take it.’footnote3 And neither, it turned out, would much of the Parliamentary Labour Party. Thus electoral sabotage, to engineer a shift back to power for the right following defeat, is a default strategy that will eventually succeed against a traumatized party membership. And the willingness to force it through will never change because a breach with the social-democratic past is baked in. The right’s commanding position within the party apparatus gives it all the tools it needs to mount blocking and sabotage campaigns.

A leader such as Corbyn can never launch the honest conversation about the past history of the party that is required or articulate a thoroughgoing critique of present party practices, such as the role of Labour-controlled councils in austerity or gentrification of the cities.footnote4 A left-wing government, should it ever come to pass with a small majority, would immediately be held hostage by the Labour right over its legislative programme. Additionally, the plp’s attacks on the left and their smear campaigns of the leadership, magnified at every turn by a hostile media, carry much greater weight with the public than they would if they came from political opponents formally outside a left-party vehicle. Labour’s ‘broad church’ and calls for unity are always on the terms of the right; the left must accept the right’s dominance, but the same loyalty to party over factions will never be reciprocated in those brief and highly irregular moments when the left grows in strength. Something has to give. So far it has been the Labour left’s backbone.

1. political cultures

What makes Gramsci such an inspiring thinker is the way he is able to integrate what he calls a ‘molecular’ mode of analysis within the framework of historical materialism. He refers to this approach in his discussion of the formation and development of a political party.footnote5 The molecular here meant the empirical details of a party’s formation from numerous sources. But molecular also meant for Gramsci, as the concept of the ‘concrete’ did for Marx, a methodology sensitive to the salient historical relations that demand conceptual refinement. So Gramsci famously unpacks and gives ‘a considerable extension’ to the concept of the intellectual in the context of the historical transformation of social relations under capitalism.footnote6 So too we need to unpack what the ‘right’ means inside Labour, since this term is a pragmatic shorthand useful for everyday political discourse but not necessarily the precise conceptualization needed to understand the contradictions at work. A conceptual model that can give us some analytical and strategic orientation towards the dynamics and flux of political contestation is required.

The Labour Party is a contradictory amalgam of different political traditions, in many ways a ‘mutant’ formation, according to Perry Anderson.footnote7 There is conservatism (e.g. Blue Labour), economic liberalism, social liberalism, labourism, social democracy, even socialism. A political party is defined not by the exclusive ownership of political philosophies, which in fact are shared with others, but by the proportions and relations of these political cultures within the party structures, and by the hierarchy of resources of power and prestige that agents identifying with these political cultures can mobilize. Socialism obviously is the most residual in numbers, power and prestige within the Labour Party; in practice even those who would self-describe as socialists in their personal beliefs, espouse at the level of policy essentially social-democratic proposals, understandably, given forty years of defeat. Judging by the surprise election of Corbyn in 2015 under the new one-person one-vote system, and then his re-election in 2016 facing the plp’s candidate Owen Smith, social-democratic sentiments have their base in the party membership. Judging by the way the plp has effectively declared war on the members—with individuals being expelled for absurd reasons and constituency parties suspended—social democracy appeals to only a minority of Labour mps. In June 2016, in the wake of the Brexit Referendum, 172 Labour mps voted in favour of a motion of no confidence in Corbyn; only 40 mps voted against. If Blair’s leadership of the party is taken as an index, then economic liberalism and social liberalism constitute the hegemonic political forces within the plp. Labourism, too intellectually decrepit to assert any autonomous leadership, is sullenly subordinate to Labour’s new master discourse, Deputy Leader Angela Rayner the new John Prescott to Starmer’s Blair.

Rise of social liberalism

Social liberalism is a historically variable philosophy. In its more heroic earlier period it emerged as a break with economic liberalism, in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. This was the ‘new liberalism’, seeded by philosophers such as T. H. Green, D. G. Ritchie and L. T. Hobhouse, which undertook the work of rehabilitating the state in liberal thought as the necessary co-ordinating force without which the good society, once expected to emerge naturally from the market, would remain still-born.footnote8 It eventually fed into the Fabian-led political alliance between liberalism and the labour movement, and provided much of the intellectual heavy lifting for the social-democratic compromise—Keynesianism, the 1942 Beveridge Report—that emerged piecemeal in the first decades of the twentieth century, even under Conservative governments, before being institutionalized as a new historic bloc after 1945.footnote9

For Gramsci, a historic bloc refers to the intra-ruling-class compromise that, when successful, is projected downward to include large enough sections of the subaltern classes to guarantee effective social peace. Hegemony ensues when that social peace is governed more by consent and persuasion than by coercion and violence.footnote10 Still, the force of law always stands behind this social peace, nipping dissent in the bud before it can generalize—for example, arresting leading cadres of the direct-action opposition, as in the case of the activist group uk Uncut.footnote11 In extremis the force of law can become the law of force, but the more this is generalized and sustained, the more the hegemony of the historic bloc is weakened. The dismantling of the social-democratic historic bloc begun by Thatcher in the 1980s was one such moment, when an old hegemony was receding, a new one emerging and in the interregnum, the law of force could be clearly (perhaps too clearly) seen; no more so than in the heavily militarized policing of the 1984–85 miners’ strike.

Yet by the 1990s, in order to secure its rule, economic liberalism had to tilt from brute coercion and start to reproduce itself with a greater role for consent. Social liberalism was to become a key ideological resource in this, fashioning a rapprochement with economic liberalism after decoupling from social democracy. Vis-à-vis this transition, Blairism was perhaps not quite the intellectual vacuum Anderson accuses it of being in his recent panoramic survey of the long British crisis.footnote12 As the embodiment of liberalism’s triumph within the party, Blairism transformed the political cultures of both the Labour Party and subsequently the Conservative Party, insofar as the latter tried to remake itself under Cameron on the New Labour model. This reversed the earlier pattern of Thatcherism influencing New Labour, but the crucial difference was that liberalism’s resurgence was lashed to a catastrophic surrender on political economy. On the broader cultural terrain, as Žižek noted, multiculturalism became the logic of multinational capitalism, and New Labour was part of that international trend.footnote13 The openly reactionary values of racism, sexism, homophobia and xenophobia exemplified by Thatcherism and coupled oddly with international capitalism, were to be officially replaced with public commitments to diversity and equal opportunity in order to neutralize significant sources of discontent within the framework of global economic liberalism.

Economic fractures

Thus social liberalism offers economic liberalism an alternative partner in the battle for political power. At this point the ‘social’ in social liberalism undergoes a fundamental change. No longer is it about the role of the state as a corrective to capitalism’s tendency to increase social stratification. Its role is to guarantee a level playing field of competition, not impose social obligations on capital. The ‘social’ in social liberalism becomes a rosily optimistic alternative interpretation of the consequences of capitalist markets. Two liberal optics in particular come to the fore and define the political terrain going into the new century. First, the atomization of community and society is embraced and, contra conservatism, is understood as the dismantling of hierarchies and barriers that prevent fairness and social mobility. The element of meritocracy that was mobilized by Thatcher(ism) came into contradiction with its regressive nationalistic cultural inclinations; but in social liberalism, meritocracy found a more credible champion. Hence under Blairism the ideology of meritocracy swept across the policy discourse of institutions, not just in politics but in education and the cultural industries as well.footnote14 After 2010, the alliance between the social-liberal wing of the Conservative Party and the Liberal Democrats in the Cameron–Clegg coalition government marked a joint party-political inflection of the dominance of economic and social liberalism (now without the Labour Party). Under austerity, the ‘social’ was increasingly linked to a combination of meritocracy and charity, with the voluntary and third sector stepping in to fill the gulfs in social provision. Hence photo ops of Tory mps beaming with pride at their local foodbank.

Second, and more difficult for the left to gain a critical purchase on, the international dimension of the capitalist market was celebrated for its cosmopolitanism. Of course, Marx also recognized the progressive potential of capitalism’s drive to break up national seclusion, tearing up ‘feudal, patriarchal, idyllic relations’ and establishing a ‘cosmopolitan character to production and consumption in every country.’footnote15 But liberalism is one-eyed about the progressive side of capitalism and, in its new alliance with economic liberalism, has little to say about the destructive aspect of capitalist development. The key political debate on this question was of course around the European Union which became, following the shock defeat in the 2016 referendum, the totemic governance structure of Reason itself for much of the liberal middle class. The referendum crystallized long germinating trends. ‘The sheer magnitude of the fracture between the globalized middle class and the anxious majority is clear’, wrote Rob Ford shortly after the 2016 vote. Along with Matthew Goodwin, Ford has been an ambivalent chronicler of the ‘older, white, socially conservative voters in more economically marginal neighbourhoods’ especially in Labour heartlands.footnote16

A more explicitly leftist account of an emerging hard-right ‘structure of feeling’footnote17 conducive to old-style conservativism was provided by Winlow, Hall and Treadwell in The Rise of the Right. Ventriloquizing the English nationalism that was the subject of their ethnographic research, they found a deep hatred of the liberal ‘centre’:

The absurd and immovable commitment these politicians displayed to the vague categories of ‘openness’ and ‘diversity’ indicated quite clearly how divorced from the real world they had become. The trendy new language of multiculturalism, and the actual policies and political commitments that underpinned it, marginalized the very communities that during the 20th century had enabled the country to grow to become a genuine force on the world stage. The white working class were now dismissed as idiotic, slovenly and atavistic barbarians . . .footnote18

Nor is this a peculiarly English or British phenomenon, since the forces shaping politics are cross-national and international. Christophe Guilluy finds a similar cleavage and need to get beyond the terms of the debate of the main conservative-liberal interlocutors at work in France.

French society is not divided between enlightened partisans of progress and their uncultivated and blinkered adversaries. The true divide is between those who stand to gain from globalization, or at least have the means to protect themselves against occasional misfortune, and those who stand to lose from globalization, who are powerless to withstand its merciless onslaught.footnote19

Hence the genius of the 2016 Leave campaign slogan: Take Back Control. That could have been contested from the left in both the 2017 and 2019 elections with something like a promise for a constitutional convocation of the kind that has been successful in Venezuela and Bolivia, and a step towards a genuine popular sovereignty, a genuine taking back control. But such a vision would have required a more sweeping counter-hegemonic strategy than the left in Labour could manage. The question of immigration, linked to cosmopolitanism of course, posed a particular problem for the left, given its historic commitment to proletarian internationalism and support for those fleeing poverty, state terror and war. Although Corbyn tried to re-frame the question in terms of reining in the business propensity to use migrants as a means of acquiring cheap labour, this was a minority discourse, and certainly not supported by most Labour mps, for whom the thought of curtailing the freedom of private property to buy labour at the price it could find it, was frankly undesirable.

2. a conceptual model

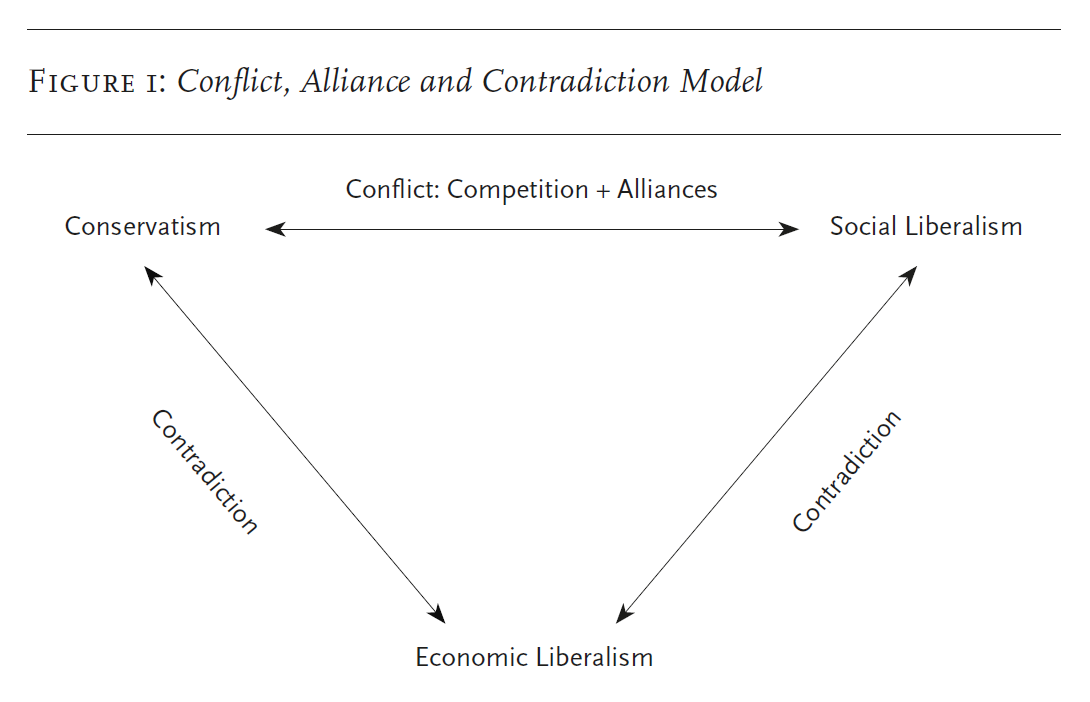

Moving up a level of abstraction to capture this more schematically, we can understand recent political history in terms of a model built around the dynamics of competition, alliances, contradictions and, potentially, fissures. The principal players are economic liberalism, conservatism and social liberalism, all three cutting across party-political entities. As Figure 1, below, indicates, the vectors of competition and alliance structure the relationship between conservatism and liberalism as they vie for moral-political leadership of economic liberalism. While they compete electorally through their party-entities, they are allied by their shared support for economic liberalism. Conservatism and social liberalism are to be understood primarily as political cultures and cultural politics, or as state and civil-society agents. Economic liberalism essentially entails capitalist market dynamics, with minimal social obligations imposed. But conservatism and liberalism—in the uk context—represent differential interpretations of the institutional frameworks within which the buying and selling of commodities is to take place. Economic liberalism is not simply about unfettering the market, but embedding it in the ‘rule of law’.footnote20 If the differences between Blairite liberalism and Thatcherite conservatism were, at an economic level, primarily tactical, the differences on questions of international governance structures and their relation to the nation-state have grown to be strategic.

Those differences are theoretically explicable when we classify the relation between the political cultures and economic liberalism in terms of contradictions. This means that economic liberalism has the potential to negate the moral-cultural and political preferences of the respective political cultures. Such negations in turn channel back up into the competition-alliance dynamic and introduce the potential for fissures and fractures in the alliances. The competition starts to move outside the boundaries of the hitherto existing policy consensus. The uk’s relationship to the eu is the preeminent contemporary example.

Readers may detect the base–superstructure model at work here, but this schema nevertheless aligns with Gramsci’s prioritization of politics—and we may add, the significance of culture. ‘It may be ruled out’, writes Gramsci in his critique of economism, ‘that immediate economic crises of themselves produce fundamental historical events.’footnote21 Thus the financial crisis of 2008 interacted with and was mediated by the political cultures in play within the historic bloc, including residual popular nostalgia for social democracy, no matter how unrepresented those sentiments were by the main political parties or how disorganized their expression.

While social liberalism has promoted economic liberalism since the 1990s, economic liberalism generates consequences that threaten to liquidate the moral-cultural universe of social liberalism. The tendency towards monopoly concentrates power in ways that liberalism, if it is minded to self-reflexive ruminations, finds problematic; the tendency towards uneven development contradicts liberal claims to be ameliorating conditions for the world’s poor; the tendency towards rent-seeking behaviour in the form of land, credit, patents, etc., offends liberalism’s belief that the core of the capitalist system lies in progressive and dynamic technological change; the tendency to use authoritarian state power and increasingly surveillance offends liberalism’s protection of individual rights, while the tendency towards the destruction of material security, which economic liberalism generates, threatens to produce the regressive nationalism that undermines liberal cosmopolitanism.

Conservative compensations

While conservatism also promotes economic liberalism, it too faces contradictions. Conservatism’s cherished institutions in which the ‘wisdom of the ages’ is preserved are threatened by capitalism’s revolutionary thirst for change. Economic liberalism’s commodification of the body undermines the Christian foundations of conservatism; its atomization of social relations erodes those smaller-scale units of social belonging, the family, the community, that conservatism favours; and its ever extending internationalism threatens the symbolic and economic foundations of the national imaginary which conservatism has made its own. As with liberalism, deepening economic inequality threatens core conservative values and institutions. In the present case, the supranational British state is in danger of breaking up as subaltern nations, and their state complexes (particularly Scotland and Northern Ireland) posit independence as a means or an end that will resolve these contradictions.

The close links between cultural politics and political cultures means that the latter can turn ‘structures of feeling’ at work in civil society into forceful organized outcomes, as with Brexit. However, there are important differences between the way this plays out with conservatism and with liberalism, stemming in turn from their different relations to economic liberalism. For the relationship between economic ‘base’ and ‘superstructure’ (both state and civil society) in the case of conservatism is deeply contradictory rather than isomorphic; yet this is exactly what gives conservatism its creative flexibility and cultural energy. By being in contradiction with key dynamics of capitalism, conservatism is powerfully mobilized as a compensatory culture. It works typically through the Freudian mechanisms of displacement and condensation, which explains why it has such affective power. By contrast, liberalism is a more isomorphic extension into political and cultural discourse of at least the phenomenal life of capitalism—rationalism, equal exchange, the individual as free-floating atom, contractual relations, competition, internationally extended value chains, etc. Yet it is precisely this match between capitalism’s surface life and liberal political culture that makes liberalism less able to offer emotional compensation for the negative outcomes of capitalism. This gives conservatism something of an edge in abnormal times. Still, the contradictions can be enabling and disabling for both political cultures in their competition with one another, depending on what use they and their adversaries can make of them. The model therefore needs to be able to cope with complexity, dynamic change, structural contradictions and agency.

Liberalism for example uses capitalism’s internationalist tendencies to play a leading role in developing cosmopolitan institutions and cultures. The threat posed by the eu in terms of creating new bonds of identity and identification that bypass the national imaginary and its institutions, where conservatism has always been strong and liberalism has been relatively weak, is precisely why conservatism has the means and the motive to react with fury to such endeavours. It was the conservative brand of Thatcherism Redux that proved best placed to marshal the various discontents of economic liberalism and, through the political arts of displacement, to find a way back from the wilderness years of 1997–2010. With the Cameron–Clegg social-liberal project rapidly compromised by harsh economic-liberal austerity, a revived attempt to combine an economy open to international capitalism (but uncoupled from the eu) with a political culture of nationalism has increasingly made the running—and gained rocket boosters after the 2016 Referendum. Its party-political representatives were ukip and what became the European Research Group wing of the Conservative Party, the two working together in a tacit alliance.

If capitalism’s supranationalism cuts against and contradicts appeals to national sovereignty and cultural homogeneity, it is easy enough to portray the insecurities it generates as stemming from eu ‘bureaucracy’, metropolitan elites and migrant labour, through the discursive processes of displacement and condensation of which ukip’s Nigel Farage was a master. Liberalism cannot in fact compete with the discourse of nationalism when the chips are down, for what does it have to counter the tangible appeals to place and people, the mythological history or the institutional bulwarks of the British state, in which conservatism has profitably invested so much power? For example, in its long moral-political struggle against the eu, conservatism grounded the discontents of an older generation of voters by mobilizing and reworking their version of the national imaginary around the Second World War, with the eu as the enemy without and the Germans once again trying to defeat Britain, this time through front institutions and without firing a shot.footnote22

3. classes and parties

Fissures between former partners in a historic bloc vent deep down, producing crises between the political philosophies, the parties in which they are distributed and the social classes. According to Gramsci, politics, understood historically, is the organized orchestration of the superstructure with the ‘structure’ (the social classes). When there is a significant disagreement between the leading classes as to what actually is in their collective interests, the bloc undergoes convulsions and ‘social classes become detached from their traditional parties.’footnote23 In broad terms, we have seen this detachment happen in Scotland, with the working class breaking with Labour and switching to the snp in the early 2000s, in relation to Holyrood, and then in relation to the Westminster parliament in 2015, when the snp took 40 of Labour’s 41 Scottish seats. The main driver here was New Labour’s contempt for the social-democratic aspirations of the Scottish working class, aspirations which the snp seemed better placed to meet.

In England, though, working-class allegiances were much more up for grabs between parties and political cultures. Generally the shift was to the right, towards conservatism, as incarnated by ukip and then by an increasingly ‘ukipized’ Conservative Party in the run up to the 2019 election. In between, at the 2017 election, there was a moment when Corbyn’s Labour Party appeared to hold the line and offer a more radical social-democratic prospectus than the snp, which was increasingly shifting towards social liberalism. But the cross-currents of Brexit in England and the recent break with New Labour in Scotland proved a barrier too high to surmount.

Electoral struggles

Elections offer a snapshot of the struggle for hegemony between the political cultures, as well as of the parties battling for the leadership of those political cultures, with their particular combinations of them. The distinction is important. Would ukip or the Tories triumph as the party-political vehicle for nationalistic conservatism after 2010? Would Labour, the snp or Liberal Democrats triumph as the party-political vehicle of liberalism, or alternatively under Corbyn, could Labour redefine itself as a return to social democracy?

In the 2014 European Parliament elections, ukip topped the poll with 27 per cent of the vote, Labour came second with 25 per cent and the Conservatives came third with 23 per cent. ukip’s electoral popularity had surged after austerity became the policy response to the 2008 global crisis following the arrival of the Coalition government in 2010.footnote24 Thus liberal conservatism and social liberalism—the Coalition government—clearly sowed the seeds for its own defeat on the question of Europe. In the general election of 2015, ukip captured nearly 4 million votes, just under 13 per cent, eclipsing the Liberal Democrats as a third party. Yet the first-past-the-post majoritarian system meant that ukip failed to win a single parliamentary seat. It nevertheless saw big increases in its working-class electoral base, drawing support ‘along England’s more financially disadvantaged east coast, in Kent, Essex, Norfolk, Lincolnshire and Yorkshire, and also in the north east where its average share of the vote (17 per cent) was its highest across the country.’footnote25

Yet the high barrier to new party representation in parliament meant that the votes ukip was now taking from both the Conservatives and Labour could be re-canalized, if the concerns mobilizing older, white, financially vulnerable and educationally impoverished voters could be reconciled with these parties’ broader political agendas. Of the two, the Tory Party was best placed to do so, since it had the Euro-sceptic European Research Group as a high-profile and increasingly powerful lobby within it. Labour, by contrast, had a parliamentary body and membership overwhelmingly oriented towards the eu, and that sentiment was to be ruthlessly exploited as a wedge issue by Corbyn’s opponents inside and outside the party. In 2017, Corbyn’s promise to respect the outcome of the Brexit referendum bought space for a renewed social-democratic prospectus to get a hearing. Labour won some 12.8 million votes, or 40 per cent of the total, against the Conservatives’ 13.6 million votes or 42 per cent. The two main parties squeezed ukip’s vote down to just under 600,000. Forty-five per cent of ukip voters from the 2015 general election voted for the Conservatives, and only 11 per cent went for Labour.footnote26

In 2017, the Conservatives had a net loss of 13 seats and Labour a net gain of 30 seats. Labour secured a share of the vote similar to that won by Blair in 2001 and a swing of 10 per cent, comparable to Blair’s 1997 landslide. Of course, as the right within the party were keen to point out, although Labour did better than expected, much better, it did not win enough seats to achieve power. ‘Labour Road Map’, a report by a rather anonymous group of ‘Labour activists’ claiming to champion a ‘pragmatic Labour vision that widely resonates and persuades the public’, concluded that these were ‘results without success’ in terms of winning parliamentary seats. Instead, the vote share indicated deepening levels of support in constituencies already held by Labour, especially in the cities and university towns, but not a sufficiently broad appeal to overturn Conservative majorities.footnote27

In mitigation, the line between success and second place was often incredibly tight. Excluding Northern Ireland, there were 48 constituency seats where the winning majority in 2017 was less than 1,000 votes. Of these, Labour came second in 21 seats, losing Southampton, Itchen by only 30 votes (Figure 2, below). Had all 21 of those seats changed hands, the Conservatives would have been on 303 seats and Labour on 283. The total number of votes in play across those 21 seats was 8,584. In an election where more than 26 million voted, that is a statistically insignificant figure. The point about this is not to play fantasy political outcomes, but to remember that the 2017 Labour manifesto was popular, credible and—in a sense probably not meant by the Labour Road Map group—a ‘pragmatic Labour vision’ that ‘persuades the public’.

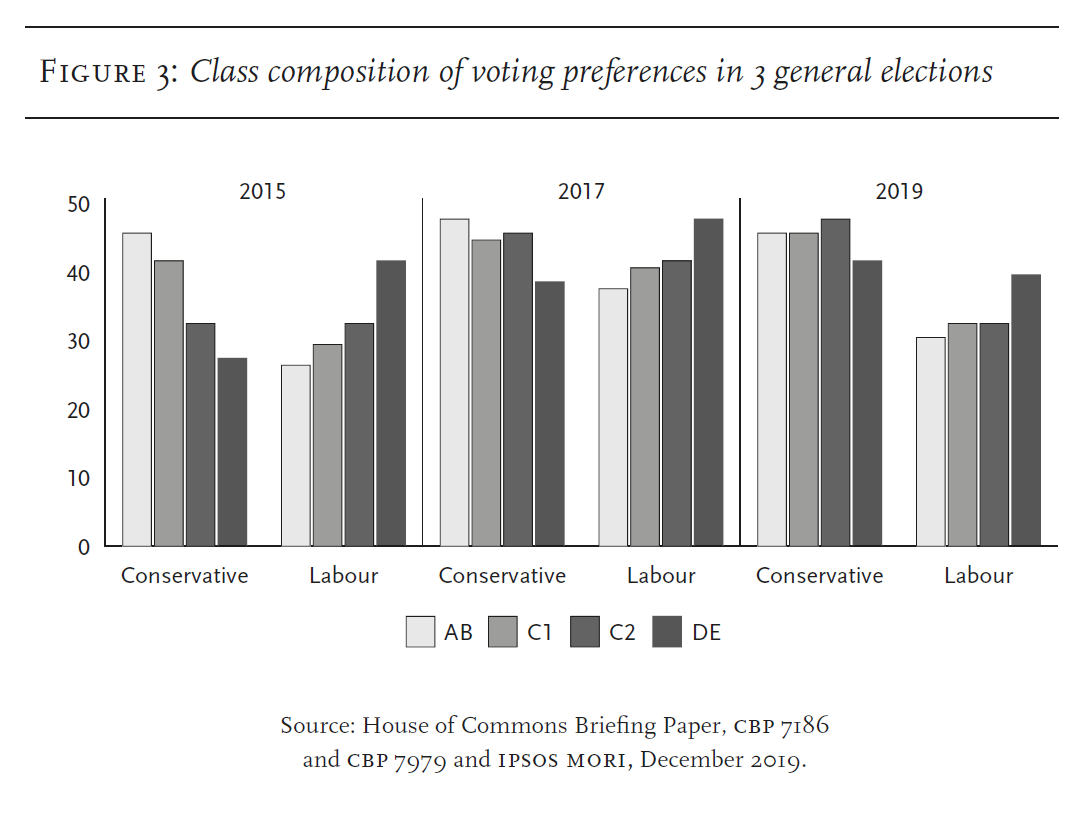

Another mitigating point is that the Corbyn leadership was working in a context in which it had inherited (rather than caused) the long-term negative trend of class de-alignment for which New Labour was responsible (including the catastrophic loss of Scotland). A comparison of the three general elections of 2015, 2017 and 2019 indicates that Corbyn was partially able to hold those trends in check in 2017. But once combined with Brexit, those trends in many ways came to a culmination in 2019 (Figure 3, below). In 2015 the Tories outperformed Labour (under Edward Miliband’s leadership) in the c1s very comfortably (41 to 29 per cent) and tied with them for the c2s. The des still voted substantially for Labour (41 to 27 per cent). In 2017, the Conservatives marginally increased their hold on the c1s, while Labour increased its share of the c1 vote by 11 per cent, a significant improvement. Nevertheless, the Tories increased their hold over the c2 vote by 13 per cent between 2015 and 2017, a warning sign that Labour could be on the cusp of significant shifts and that Theresa May’s strategy of corralling the Brexit Leave working-class vote almost worked. What stopped it, partially, was that Labour also increased its share of the c2s by 9 per cent. Of course these ‘abcde’ uk social categories—devised in the 1960s for use by the advertising industry—are not unproblematic, even on their own terms. In particular there is evidence that the c2 category is fragmenting between those located in the expanding service sectors of the cities and university towns, and those in the former industrial heartlands made up of small towns and villages in the north.footnote28

In 2017, the Conservatives were also doing well amongst the des although Labour managed to stay ahead. But again, there were clear signs that the Tories had momentum in class groupings that had historically been Labour strongholds. What was happening in Bolsover, a former mining district and historically one of Labour’s safest seats, was telling. Left-Labour mp Dennis Skinner’s vote dropped by nearly a third between 1997 and 2015, from 35,000 to 22,542. In 2005 Skinner had taken 65 per cent of the vote. Then came Brexit, pressing down further on those longer-term trends. In 2017 Skinner’s majority shrank again. It was another clear warning sign that the former heartlands in the northern small towns were preparing for a historic shift. All it would take was a shift on a symbolically loaded issue for quantitative change to become qualitative.

Finally, in 2019 the Conservatives secured 45 per cent of the c1s while Labour collapsed to 32 per cent. The Conservatives took 47 per cent of the c2s while Labour again won only 32 per cent. And the Conservatives increased their share of the des to 41 per cent, while Labour fell to 39 per cent. Labour’s changed stance on Brexit, promising now to hold a second referendum on a deal with the eu, could no longer stay the momentum towards nationalistic conservatism as the hegemonic solution to the problem of the 2016 referendum result. Of the 54 seats that Labour lost to the Conservatives in 2019, 52 were in areas that had voted leave in 2016—including Skinner’s.footnote29

To Brexit we must add the fact that 2017’s close but not quite good enough result terrified Corbyn’s opponents inside and outside the Labour Party. Evidence from the leaked dossier on the right’s hyper-factionalism showed that Labour’s 2017 campaign was not helped by senior staff inside party headquarters, who were working for a defeat in the hope that this would trigger Corbyn’s downfall. According to the dossier, senior staff bemoaned on WhatsApp evidence of Labour doing well in the run-up to the election and were left distraught by the eventual result. As the Independent reported:

An election-night chat log shows that 45 minutes after the exit poll revealed that Labour had overturned the Conservative majority, one senior official said the result was the ‘opposite to what I had been working towards for the last couple of years’, describing themselves and their allies as ‘silent and grey-faced’ and in need of counselling.footnote30

It is clear that these political currents in Labour will want to bury the memory of the 2017 general election and any evidence that there is popular support for a left social-democratic agenda.

4. labour’s contradictions

In retrospect, when Labour Party members (twice) defied the wisdom of their mps and elected Corbyn as their leader, this was, as Anderson notes, ‘a gust of enthusiasm, not confined to youth, attracted by sheer novelty, rather than driven by conviction.’footnote31 Digging into this unfortunately accurate assessment a little more, we can say that while the membership appeared briefly willing to consider a rupture with economic liberalism, they remained in thrall to the hegemony of social liberalism, no more so than on the question of the eu. Although they wore the T-Shirts, ‘Love Corbyn, Hate Brexit’, psychologically and politically, they were transitioning away from Corbyn in favour of ‘lifestyle horizons’.footnote32 As Michael Chessum, a Momentum activist and national organizer for the pro-Remain lobby, Another Europe is Possible, warned in the Guardian: ‘Labour cannot expect to demoralize its activist base by choosing to implement a policy they regard as a fundamental affront to their values, and then just talk about school funding instead.’footnote33

The Corbyn leadership’s greatest electoral triumph, the 2017 destruction of the Tory majority bequeathed to May by Cameron, was also, as the cunning of history would have it, the foundation of its downfall. For it emboldened a Remain campaign that had been practically dead with the prospect of being able to block Brexit in parliament. The 2017 party conference season saw the launch of the Labour Campaign for a Single Market, backed by openly anti-Corbyn right-wing Labour mps such as Chris Leslie, Chuka Umunna and Stella Creasy and pulling in wider support. The 2018 Labour Party conference was flooded with 150 motions on Brexit, 84 of which specifically called for a people’s vote. These motions drew inspiration from a plethora of organizations: Another Europe is Possible; Love Socialism, Hate Brexit; Labour for a Socialist Europe and Open Labour.

On the eve of the 2018 conference, a YouGov poll found high levels of support for a second Brexit vote amongst trade-union members: 56 per cent of gmb members, 59 per cent of Unite members and 66 per cent of Unison members supported a second vote. In part, this may reflect the shift towards a better qualified, public-sector membership within the uk’s now much smaller trade-union movement, covering 24 per cent of employees, down from 53 per cent in 1979. Unionization rates are higher among those in managerial and supervisory roles, among middle-income as opposed to lower-income earners and among those with a university degree, compared to those with no further-education qualifications. And while public-sector workers make up only 18 per cent of the uk labour force, they constitute 64 per cent of trade-union members. footnote34 YouGov also found that 86 per cent of Labour members wanted a second referendum and only 8 per cent were opposed.footnote35 This may partly be explained by the fact that Labour Party membership has, since New Labour, increasingly become middle class, offering less opportunity for members to come into contact with viewpoints outside their class bubble. A 2002 study provided evidence that the socio-economic demographics of Labour membership changed in the 1990s, with a growth in the ‘salariat’ from one-half to two-thirds, while the proportion of working-class members fell from one quarter to one-seventh.footnote36 By the time Corbyn was leader, 77 per cent of the membership fell into the abc1s categories for social-class identification according to one study.footnote37 The push for a second referendum fed into a deepening class-culture fissure between the membership and important segments of Labour’s working-class electoral base, for whom an important democratic principle (respecting the referendum outcome) was now intertwined with existential questions of identity (the sovereign nation).

For the membership, however, an opposing identity-politics position was forming in a dialogue of the deaf. Here an important democratic principle (informed debate) was now intertwined with existential questions of identity (Britain as part of a European social-liberal polity). Watching young people chant Corbyn’s name at the Glastonbury Festival two weeks after the June 2017 election, the leadership cadre of social liberalism might have seen the opportunity to use the eu as a wedge issue. While Corbyn’s supporters were open to policy sentiments that offered a route back to social democracy (now anathema to social liberalism) they were also aligned to—that is, under the hegemony of—cultural values much closer to liberalism, of which the eu seemed to be the single most important symbol. In this, the links between social liberalism’s leadership cadre and important sectors of the media were crucial in shaping broader public perceptions of Corbyn’s leadership.

Driving the wedge

Gramsci had noted that national newspapers—he cited The Times in England and Corriere della Sera in Italy—can have important leadership functions, even on political parties, acting as an alternative ‘intellectual High Command’.footnote38 In assessing the role of the Guardian as an intellectual High Command to weaken the Corbyn leadership we might begin by noting how quickly they set the terms for the later monstering of the man and his politics. Three days after Corbyn won the leadership in 2015, leading Guardian columnist Rafael Behr wrote an article describing Corbynism as ‘a kind of Faragism of the left’ (the left and the right as mirror images of each other), as not competent in professional politics (a rich seam that would be mined ad nauseam) and as representing a ‘contempt for Parliament’, a trope that allowed liberalism to relive its worst Cold War days. The result was ‘bad for all moderate politicians’, we were told. Already, at this early stage, the Guardian had identified three frames that were to dominate its coverage of Corbyn.footnote39

At this point many of the online readers’ comments below the piece were critical of Behr. The emerging gap between the Guardian’s editorial line and sections of its readership perhaps reflected the one that had opened up between the plp and the party membership. But there was one point of attack that Behr made, a fourth frame, which received less attention below the line, presumably because of its potential to be a wedge issue. This was his argument about Corbyn’s ‘obvious dislike for a European project he sees as the conduit for corporate interests and pro-austerity economics’. This frame—later elaborated as Corbyn’s dishonesty, secret desire for Brexit, stubborn refusal to back the obvious need for a ‘People’s Vote’, etc—combined with and supported by the others, and already in place before Corbyn’s leadership was three days old, provided the ammunition for a sustained assault. The Guardian specializes in wringing its hands at the state of the world, but when a policy came along offering to address some of those wrongs even only modestly, its response was to launch a vicious propaganda campaign to ensure it never came to pass.

Brexit was a double wedge issue, the gift that kept giving for Corbyn’s opponents. It helped force a rift between the cultural values of Corbyn’s supporters and their initial backing for an economic programme that broke with economic liberalism. It also created a fatal fissure between the membership and the broader electoral base in the northern constituencies. Another related issue that limited the political culture of the membership was their structural role within the party, a subaltern role that the members have deeply internalized. When the plp declared war on the membership, the membership did not respond in kind. Behr’s jibe about Corbyn’s supposed ‘contempt’ for parliament, an institution in which he has spent most of his working life, may have been provoked in part by hopes that Labour would become more of a social movement under his leadership.footnote40 Corbyn represents a strand of left thinking that has a critique (which is not the same as contempt) of an exclusively parliamentary focus for the very good reason that such a focus cements politics into the historic bloc. As Stuart Hall noted, the Labour Party is exceptionally good at failing to connect with ‘popular feelings’ and this is intimately connected to its fetishization of parliamentarism to the exclusion of any political space or practice outside the ‘parliamentary mould’. Any political practice not emanating from or directed to the House of Commons ‘produces in its leadership the deepest traumas and the most sycophantic poems of praise for parliamentarism.’footnote41

Writing shortly after the 2017 general election, Hilary Wainwright linked the prospect of a Corbyn government to a long running theme in her work, the need to counter the hostile retaliation of the established power structures with ‘power-as-a-transformative-capacity’.footnote42 These arguments are well rehearsed on the left, but it must have been alarming for the social-liberal hegemons to see the leader of the Labour Party mulling the importance of popular power as a counter to state and capital. Instead of consecrating the split between political power and material reproduction—a split that channels all politics to accept private monopoly control of vast productive assets—this threatened to start tackling the economic dimension of political power, and the political dimension of economic power, the first steps towards a realistic strategy of socialist transformation.footnote43 Hence the scorn poured on Corbyn’s aspirations, the cries that Corbyn was not serious about winning elections, that he was not ‘professional’, that he threatened to turn Labour into a rag-tag protest movement.

Interestingly, in the 1990s, both Blair and Brown tried to revitalize local party constituencies, as the torpor of the old bureaucratic-Labourist tradition had whittled away at membership numbers. But the model of community activity that they had in mind was more along the lines of polite civic participation for a newly enlarged middle-class membership, rather than engagement in working-class struggles. In the mid-1990s party membership began to rise as disgust with the political and moral corruption of the Conservative Party grew. From around 270,000 in 1993, it rose to 400,000 in 1997 but then declined rapidly to 200,000 by 2009 as it became clear that Blair and Brown had completed the liberal revolution of Labour policy.footnote44 By 2015 it was under 200,000, before Corbyn’s rise almost trebled that number, with party membership climbing to a high of 575,000 in July 2017.footnote45

The necessary disconnection between party membership and activism produces a contradiction for the dominant model, namely declining numbers and vitality. Yet it is a price that has to be paid in observance to what we may call the pmq model. The weekly jousts between the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition are vital for those inside the Westminster bubble, although for the vast majority of people, they are utterly irrelevant. But the importance of pmqs may be taken as a symbol of the domination of the Parliamentary Labour Party over the membership, evident in the relative ease with which mps have fought off mandatory reselection even when it was available as a trigger to the membership.footnote46 While Momentum brought a welcome activist support base for the Corbyn leadership and innovative campaign ideas about the use of social media,footnote47 its political positions on key questions, such as Europe or the anti-Semitism smear campaign, were weak, naive and uninformed by hard-headed analysis and political culture.

5. class feelings

In February 2020, just two months after Corbyn’s shattering defeat, I was at the Soho Theatre in London watching Chris McGlade, a comedian and political activist from Redcar, Teeside. McGlade was evidently enjoying himself as he upended liberal metropolitan assumptions with his non-racist, non-sexist critique of political correctness. McGlade is also an ‘anti-globalist’, an ambiguous political discourse for sure, evident in the fact that he unabashedly declared that in the 2019 general election he had voted Conservative for the first time. He was not alone: the Redcar constituency has just elected a Conservative candidate for the first time. McGlade is an example of what Gramsci called an organic intellectual, someone with a close lived relationship with the needs of a social group and who can articulate those needs and interests in a persuasive and compelling fashion, in a language that is widely understood; someone who can organize opinions and perceptions, but typically also action and behaviour.footnote48

The electoral choice in 2019 of McGlade and the 18,810 other people who voted Tory in the Redcar constituency, along with his whole performance that night at the Soho Theatre, with its self-conscious critique of self-satisfied liberalism, speaks volumes about the growing distance of Labour, the labour movement and the British left generally from the working class. When significant sections of that class moved, as in 2019, then all the clever social-media campaigns launched by Momentum were left stranded. The crisis and the tragedy of the left is here in microcosm, as an intelligent, articulate ‘anti-globalist’ expresses the collective predisposition to vote for a party of hedge-fund managers and other organs of finance capital, such as the last two Conservative Chancellors of the Exchequer, former senior-level men from Deutsche Bank and Goldman Sachs respectively.

A comedian may be an organic intellectual, but in a political party intellectuals of different types and from different strata are fused together for long-term effective action.footnote49 The fissure between the working class and the middle class is evident in the dominance of the middle class in Labour and amongst Labour mps. The percentage of Labour mps from manual-work backgrounds was one third in 1951, but it is less than one in ten today.footnote50 The trends driving this transformation are multiple and powerful, so much so that it is impossible for them to be reversed by an organization not completely dedicated to the task. It cannot be achieved by a minority within an organization otherwise content to continue with the current, or even a majority that lacks power over unaccountable party apparatuses. It is clear that the limits of Labour’s ambitions in this regard will be to offer the working class some Labour version of conservatism, meaning a minimal economic programme, geared primarily to help certain sections of capital (such as transport or housing) backed up with plenty of political-cultural compensations (strong on defence, law and order, immigration, etc) that are ineffective at dealing with root causal problems but may serve to keep this segment of the working class passive and acquiescent.

For a party to reconnect the middle class with organic intellectuals from the working class is to achieve in embryo and against the odds the task that must be generalized throughout civil society and the state. It cannot be done without a reckoning with neoliberal liberalism, which the Labour Party cannot begin to accomplish. And without such a reconnection there can be no political progress. The left will continue to fall under the political and moral leadership of liberalism, and important sections of the working class will be pulled further into the political and cultural orbit of conservatism. McGlade was full of class feeling and consciousness at the Soho Theatre, an example that value dissensus is not incompatible with a willingness to delegate political leadership to the dominant class group by voting Conservative. Unless the left can engage and intervene, it will not be able to inflect such class feelings into an alternative conception of the national-popular. Such engagement would be a learning experience for all sides. Among the huge barriers to be overcome in repairing the unravelling of solidarities, is the deep class resentment and suspicion now emanating from the working class to the middle-class ‘left’, whose priorities seem more and more remote every day from working-class lifeworlds.

A new social democracy?

In February 2019, Labour’s Deputy Leader Tom Watson, who was busy undermining the Corbyn leadership at every turn, announced that he was setting up a Labour group of backbenchers dedicated to ‘social democracy’ to broaden the party’s appeal. You have to admire the chutzpah. It was part of the discursive framing of Corbyn’s leadership as ‘extreme’, as outside the progressive traditions of the political mainstream. The reality is that the majority of the plp abandoned social democracy and that Corbyn’s programme was a modest attempt at reviving that political tradition. It is, as Tariq Ali memorably put it, the ‘centre’ that is extreme.footnote51 If by social democracy we mean redistribution of wealth from the rich to the rest via high taxation, converted into socialized provision and welfare support, then neither the plp nor the various ‘Third Way’ apologists are social democrats anymore but hybrids of conservatism and liberalism re-aligned.footnote52 If by social democracy we mean imposing significant social obligations on capital and controlling its international power, then the power-bloc in the Labour Party will never allow it. If we mean re-empowering organized labour by dismantling some of the most restrictive trade-union laws in the Western world, then again, social democracy has few advocates at the Palace of Westminster. If we mean reviving public services by taking privatized utilities out of private ownership and driving marketization and corporate contractors out of public funding of services, then that is a vision too large and a shift too historic for the British state (or indeed the eu) to admit as a legitimate project.

The 2017 Labour Party Manifesto was modest when measured against some of these social-democratic objectives. An investment bank to fund infrastructure projects, an idea borrowed from such bastions of revolutionary socialism as Germany and the Nordic countries; ‘moving towards’ a 20:1 gap between the boardroom and the lowest paid; corporation tax raised but still amongst the lowest in the major developed economies; the City left entirely alone; the co-operative sector to be doubled in size, bringing it in line with the land of Free Enterprise across the Atlantic; energy, water and rail brought back into public ownership; a commitment to renewables and nuclear; the abolition of university tuition fees and the reintroduction of maintenance grants; a modest enhancement of trade-union rights; a very modest council and housing-association building programme (100,000 per year by the end of the parliament); some new rights for renters that fell well short of a declaration of war on the landlord class—and so on. Modest as the policy offering was, what the ruling bloc feared was not any single one of the proposals, or even all of them put together, but rather the shift in direction a Corbyn victory would mark, the momentum that might develop and the spectre of an excess of clamorous democratic demands being reawakened at the expense of the power and wealth of the dominant groups.footnote53

The left’s relationship to social democracy, though, also needs rethinking. It tends to associate the term with the ossification of the later post-war period, a great lumbering behemoth clamping down on ‘industrial modernity’ according to Tom Nairn, skirting at times dangerously close to economic liberalism in The Break-Up of Britain,footnote54 while for the revolutionary left, it was a byword for class compromise. After forty years of defeat, the purity of revolutionary theory uncoupled from mass practice is a strange comfort. The left cannot afford to be so dismissive of a political culture that had to be broken by capital, that must be unrepresented by the dominant political parties; that expresses sentiments with which millions of people can identify; a political culture un-represented and unrepresentable by the dominant bloc (including Labour).

The left should remember not the creaking institutions of social democracy that were generating discontent in the 1960s and 1970s, but the fact that social democracy emerged out of the conflict and strife of war, revolution, counter-revolution and economic catastrophe in Europe between 1914 and 1945. It was not born in peacetime. It is clear today, post-Corbyn, that it will take a revolution to get some social democracy—that is: mass mobilization, polarization and a significant growth in class consciousness. This Corbyn did not have. There was enthusiasm to be sure, there were crowds, there was the singing of his name, but it was a spectacle that had nowhere to go and the Labour Party was unable to tap or engage with that wider sentiment. Momentum was largely turned inward, defending the Corbyn leadership, as it probably had to do in an organization whose dominant factions were on 24/7 manoeuvres against him. Again, the cost of inhabiting a house with diametrically opposed visions is paralysis.

The kind of popular power as a transformative capacity that would be needed to break through into the existing institutions of capitalist democracy so as to begin to effect change suggests we are dealing here with the paradox of a revolutionary form and a social-democratic content. But for a period of time this might be a necessary and an enabling contradiction. It would open up crucial avenues of historical experience in terms of participation, agency, problem solving, experimenting, democratizing, solidarity building, and so forth. It would be a historical experience that would at some point likely pose the old questions but which, without the historical experience itself, can only sound abstract and doctrinaire; namely whether the revolutionary form should be adapted to the social-democratic content or whether the social-democratic content should be expanded to match the revolutionary form. In evaluating that dilemma, people would have to weigh up the known risks of seriously challenging the power and wealth of an extremely violent and sociopathic class, or of remaining within the existing mode of production and accepting the associated risks of economic crisis, war and ecological catastrophe. Now, take a look at the Labour front bench and the rows of gargoyles arranged behind them and ask whether a word of truth about the dangers facing us would ever fall from their lips, or whether a muscle in their collective body would ever twitch in the direction of addressing those dangers. After Corbyn the left in Labour needs to try something new, something different; something intellectually and politically post-Labour.