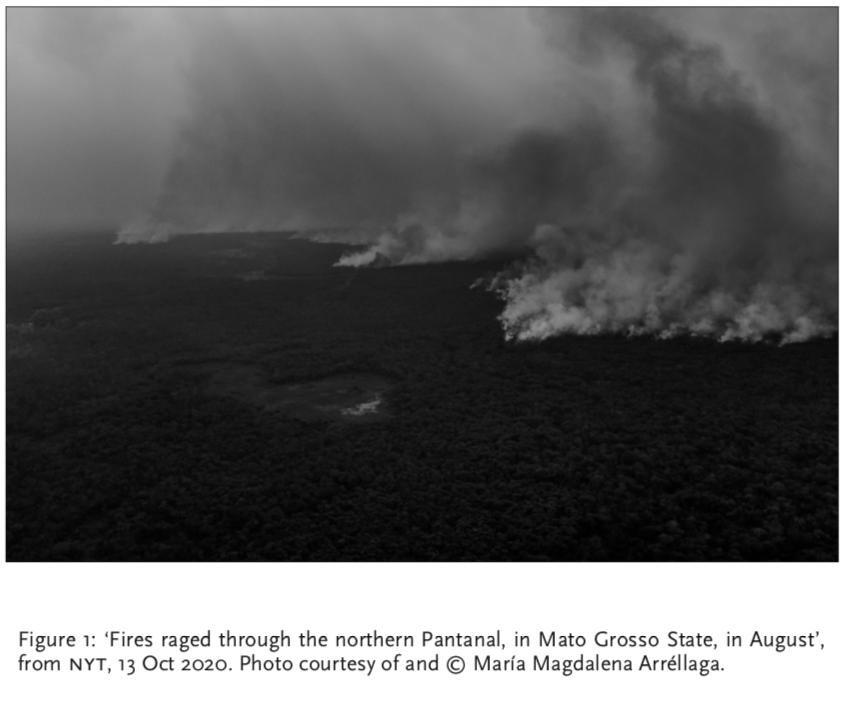

In October 2020, nasa’s Fire Information for Resource Management System released satellite imagery of the blazing wetlands of the Pantanal, on the borders of Brazil, Bolivia and Paraguay. A Brazil-based photojournalist, María Magdalena Arréllaga, added another image for the New York Times—this time a photograph, also taken from the air—of plumes of smoke rising from the same woodlands. The burning of the Pantanal, the world’s largest tropical wetlands, has razed a quarter of the region. But there are no flames in Arréllaga’s shot; the trees blur into a dark blanket of the lower half of the frame, light barely filters through the haze above; what’s in sharp focus is the line that separates the foliage from the fumes, the advancing frontier of flames. In contrast to the horror-film shots of burning houses in California and brush fires in Australia, Arréllaga’s is more ominous.footnote1

This is the latest aerial scene in the story of how humans are re-landscaping the planet in the age of climate change. But it also suggests a long-standing feature of lens-based landscape photography: it brings nature ‘home’ to viewers far away, reflecting back our attachment to—and detachment from—the wilderness. Landscape photographs have always been tasked with creating visualized connections between viewers and a natural world they would otherwise not see; making that world imaginable by making it scenic. The Alpine poster in the dentist’s office, or the nameless desert island that is the default screensaver on a new Mac, appear to offer us a window into another world. They equally serve as projections for our ideas of nature—places of Edenic wonder, escape from the drudgeries of industrial-urban grey or post-industrial cubicles. Wilderness imagery reflects, too, a potential critique of what it means to live on this side of the screen.

There is an untold story about the relationship between landscape photography and globalization. Both entered the world in the mid-nineteenth century, and they have been mutually entwined since their birth. Free trade, foreign investment and worldwide land-grabbing took hold in the 1850s, just as the English sculptor Frederick Scott Archer invented the collodion process to create and reproduce images of his work. When pioneering landscape photographers hauled their gear up through the foothills to capture the imposing forms of Yosemite or Mont Blanc, their purpose was to shoot nature as a pre-human epic. Huddled before a staged foreground, the photographer framed sightlines to gaze up at charismatic peaks. This was a documentary vision of the sublime—but also a mediated visual encounter between the capitalist world of the viewers and the natural world of the viewed. Therein lay a fundamental tension that runs through the history of the landscape image and has only intensified in what many now call the Anthropocene.

What began with representations of the sublime has culminated in images of the apocalypse. Instead of gazing up from below at the lofty peaks, the lens is increasingly poised from above, charting the advance of flames or the retreat of ice. From this angle, too, humanity’s scarring of the earth is constantly visible. The history of the landscape photograph tracks a path from reverence to conservation to survival and, lately, extinction, in the process of creating a documentary vision of both nature and capital. As glaciers melt and woodlands burn, what does this mean for the genre? Is the climate crisis also a crisis for landscape photography, struggling to find a way to portray its vanishing subject?

The answers to these questions depend on how one thinks about the narratives that entangle photography and globalization. One position is to concede that we are living through a fundamental break in modes of representation—to admit that climate change is a shock to our visual-guidance systems. The Guardian’s picture editor, Fiona Shields, has predicted that images of polar bears and forests will be replaced by shots of humans in masks, kids picking through garbage or climate refugees on the move, as visuals of the emergency. ‘Relatable images’—portraits of people, have become the most effective way to convey the crisis, as social media churns the wreckage.footnote2 But what does this mean for visions of the unrelatable? If the images are meant to stir passions and politics, Shields may have a point: if we are to break our carbon addiction, letting human stories crowd into the picture of what we are doing to nature makes sense in the Anthropocene. But putting humans front and centre challenges some foundational principles for practitioners of the genre. For so long, landscape photographers made nature majestic. Now, we might ask: are artists like Sebastião Salgado, George Marazakis and—especially, perhaps—Edward Burtynsky aestheticizing its end-days?

If the street-photographer was a fast shooter, the landscaper was slow. One didn’t ‘snap’ landscapes; one waited for the light. Henri Cartier-Bresson, one of the greatest French photographers, exemplified the street style with his pursuit of ‘the decisive moment’. The landscaper, on the other hand, worked at a different pace. The portable Leica with its 35mm film rolls was the instrument of human interaction; the large-format camera and the tripod were the staples of the panorama. The goal was not to freeze an instant in a frame but to capture high resolution with scale. It required an almost meditative style. Wet-plate negatives were cumbersome to haul and hard to set up. One had to be patient.

It also helped to have money and backers. This is one reason why so many of the early epic landscapes were the result of survey expeditions; in turn, great images could make or break a survey. In the United States, mining interests and railway companies—above all the Central Pacific, Kansas Pacific and Union Pacific—provided the backing for photographers, many of whom started their careers as surveyors. The lens was a tool to assess value. With time, the nature of value would change the value of nature. Mining and logging firms eyed landscapes for their extractable potential. Only later, in part due to the sensational impact of landscape photos, would passenger cars be added to freight trains in the promotion of tourism that helped to create the national park system.