Some six decades—three generations—ago, this journal developed a set of arguments about British state and society that were distinctive, and controversial at the time, as they have remained since.footnote1 What bearing, if any, do they have on the present conjuncture, generally—if not incontestably—described as a turning-point in the history of the country? To get a sense of the question, it may be of use to resume briefly the original theses sketched in nlr in the early sixties and their sequels. Their novelty lay in both their substantive claims, on which debate has principally focused, and their formal concerns, which set them apart from ways of thinking about the United Kingdom current on the left, and beyond, in those years. Four features in the journal’s approach to the country were new. It aimed at a (naturally, schematic) totalization of its object, that is, a characterization of all the principal structures and agents in the field, rather than exploration of partial elements of it. It sought to situate the present in a much longer historical perspective than was customary in political commentary. Its analytical framework was avowedly theoretical, drawing on then unfamiliar resources of a continental—principally Gramscian—Marxism. It was resistant to the typical habits of social patriotism, left or right, folkloric or historiographic, of the period.

The initial nlr theses were produced in response to a gathering sense of crisis in Britain. This conjuncture was compounded of a growing realization of economic decline relative to capitalist competitors abroad; popular discredit, amid scandals and divisions, of the Conservative political regime of the period, culminating in its passage from Macmillan to Home; national humiliation at failure in suing for entry to the Common Market, vetoed by France; and widespread disaffection with, and ridicule of, the hierarchical social order presiding over these misfortunes. The novelty of the nlr theses was to locate the explanation of this crisis in the peculiar class configuration of England that developed from the late 17th to the late 19th century, and the institutions and ideologies it bequeathed to the 20th. Telegraphically condensed, the principal points of this explanation, and what ensued from it, went as below. Resuming about half of the 50-plus articles written by editors of the journal in these years, taken as the most significant, the account is selective, and does not distinguish between individual signatures beyond indicating them, though their accents and outlooks of course varied. Where substantive differences developed, sometimes in the positions taken by the same writer over time, these are touched on in conclusion.

i. theses

1. A highly successful agrarian capitalism, controlled by large landowners, long preceded the arrival of industrial capitalism in Britain, installing by the 1690s an aristocratic ruling class, flanked by mercantile capital, at the head of a state shaped in their image—one which went on to acquire the largest empire in the world well before the emergence of a manufacturing class of any political consequence. The industrial revolution of the 19th century generated just such a bourgeoisie. But in not having to break feudal fetters in its path, nor possessing either the wealth or political experience of the agrarian aristocracy, the manufacturing class settled for a subordinate position in the ruling bloc, sealed by the reform of 1832, generating no hegemonic ambition or ideology of its own. Ideologically speaking, classical political economy was perfectly palatable to the landowning class, leaving only utilitarianism as a shrunken world-view of distinctively bourgeois stamp. A further powerful motivation for this abdication was fear of the world’s first industrial proletariat, which for some three decades rose in a sequence of mutinies against both the bourgeoisie and the landowner state.footnote2

2. With the crushing of Chartism, however, and the subsequent re-composition of the working class, such rebellions lapsed, giving way in the second half of the 19th century to a trade-unionism that was for the most part timorously respectable and largely apolitical, as subordinate to the established order as the bourgeoisie was within it. Nor did any disestablished intelligentsia emerge to challenge the fusion of traditionalism and empiricism that formed the cultural norm of the time. When eventually—not until 1906, exceptionally late by European standards—the working class produced its own political expression in the Labour Party, the resulting formation was dominated organizationally by the block vote of the unions who created the party to further their economic aims, and ideologically by a hand-me-down variant of utilitarianism in the form of Fabianism, counterpointed by a Christian moralism of low church descent. No threat to the state or to capital, Labour became the second party in the political system, once the Conservative Party—in keeping with the logic of aristocratic rather than bourgeois command of the dominant bloc—put paid to the Liberals after the First World War.

3. After two brief fiascos in office between the wars, then reassuring partnership with Conservatives and remnant Liberals during the Second World War, Labour eventually formed a government with a large parliamentary majority in 1945. For six years it administered the British state without modifying its constitution or significantly altering its imperial cast, contenting itself with provision of welfare—creation of the National Health Service its principal achievement—and nationalization of loss-making industries, without any structural encroachment on either the directionality or prerogatives of capital. Restoration to office of the Conservatives, under a quartet of rulers of classic aristocratic background, left Labour’s welfare reforms untouched. But Tory rule proved no less ineffectual in checking a competitive economic decline of the country—traceable back to its early low-tech manufacturing base, and compounded by the blows of two world wars to Britain’s global position, nominal victory in each case preserving rather than destroying accumulated archaisms. If the dominant bloc was to preserve its hegemony, it would have to transform itself, taking up the unfinished work of 1640 and 1832 again. If Labour, under recent new management (Wilson had just taken over) were to come to power in its stead, no socialist transformation of the country would be on its agenda, since it was not a socialist party. Did that mean it would therefore become an executor of bourgeois reform and re-stabilization of British economy and society, or might it release more explosive possibilities?

Wilson

4. Labour in office, any prospect of the former outcome vanished. Within six months, the journal could write its obituary.footnote3 Confronted by its first test with capital, a sterling crisis as the pound plunged on its entry into office, Wilson’s government rushed to appease the City by propping up the currency with an international loan and deflationary contraction, in unbroken continuity with the priorities of the imperial past. Moreover, in keeping with the now established post-war premise of these, Labour was still playing aide-de-camp to Washington—just then escalating its war in Vietnam—across the world, while pursuing its own colonial operations in Asia and elsewhere. In such conditions, in yet another failing attempt to shore up British capitalism against competitive decline, Wilson’s leading domestic objective was bound to become a bid to batten down trade-union militancy at home. That set the scene for the political turbulence of the next six years: the launching and crushing of the seamen’s strike, flare-up of student revolt, outbreak of Catholic rebellion in Ulster, emergence of neo-nationalism in Scotland, first stirrings of popular racism in England.

5. The journal’s response to this intensification of crisis came in three directions. Hailing the changing temper of the unions, which for the first time pitted major forces directly against the party they had originally created, in an overdue revolt against the deeply unequal society over which Labour presided, nlr organized the production of a Penguin Special on the rise in industrial unrest, excoriating Wilson’s red-baiting repression of the long and bitter seamen’s struggle, and welcoming the capture by the left of the big Engineering Union of the time, hitherto a stronghold of the right—while noting the structural limits of any trade-union militancy without a political organization flanking it.footnote4 Simultaneously, cresting on the tide that took currents of the ‘new left’ of the late fiftiesfootnote5 into the much broader waters of a ‘cultural revolution’ in the sixties, and taking its cue from Gramsci’s systematic concern, alone among thinkers of the Third International, with the role of intelligentsias in the organization of social consent, the journal produced another Penguin Special on the student revolt of 1967–68, seen as the beginning of a radicalization of the newest generation of British intellectuals.footnote6 In aid of that revolt, this outlined a map of the prevailing conformism of post-war national culture across the social sciences and humanities—tracing its degree of dependence on White émigrés of conservative stamp, and stressing the historic lack in Britain of either a classical sociology or a native Marxism: a dual myopia that precluded any critical understanding of the totality of insular society, against which campus iconoclasm should take aim.footnote7

6. Meanwhile, the Scottish National Party (snp) had trounced Labour in a sudden, unexpected by-election victory in Scotland, giving the party its first seat at Westminster since the war. Seen from without, this could be viewed as a welcome premonition of possible future dismemberment of the imperial British state. But viewed from within, the snp had not escaped the inherited deformations of Scottish nationalism—its ‘three dreams’—each detached from the realities they sought to represent, and from which caustic historical analysis was required to liberate it: first the fixations of Calvinism, then the illusions of Romanticism, then the self-deceptions of belief that modern Scotland was a colonized society, rather than long an eager partner in a vast colonial empire. A sane Scottish nationalism, necessarily socialist, would have to settle accounts with these disabling oneiric legacies of the past.footnote8 What then of England? An x-ray of Enoch Powell’s literary output—poetic and forensic—laid bare the ways in which a dormant English nationalism, never popular in character since the masses had played so little role in creating the imperial British state that enfolded it, could acquire a more aggressive cast in conditions of establishment crisis.footnote9 Once stale middle-class tropes of a Georgian countryside were displaced by raw appeals to anti-immigrant racism, the seeds of radical forms of reaction were being sown, even if—this being Britain—these would no doubt assume outwardly traditional guise.

Heath

7. In 1970 Wilson, having broken one promise after another and left the economy little better than when he took office, was succeeded by Heath, who set off in a sharply different direction. Jettisoning pro-forma gestures of dirigisme in favour of letting markets take their course, the new Conservative administration imposed draconian limits on strike action at home, and veering away from the United States, re-applied for entry to the Common Market abroad. Was this the overdue rationalization of bourgeois state and society at which Labour had so conspicuously faltered? Successive diagnoses in the journal diverged. At the outset: in breaking with industrial conciliation at home and servility to Washington abroad, was Heath offering capital competent class leadership—even if there would be a price to pay in provoking a collision with the unions, which could radicalize them, and in putting Britain’s chips on Europe, which was bound to weaken cherished totems of the old order, sapping the integrity of Britain’s constitution or absence of one?footnote10 A year or so later, when defiance of the government by dockers, miners, railway, shipyard and postal workers had forced Heath to retreat: had not turning industrial disputes over to the courts been a major miscalculation, the opposite of a rational bourgeois strategy? Did that not risk putting in the front line of crushing union resistance not the government which could claim an electoral mandate, but the judicial branch of the state, whose facade of neutrality, crucial for class purposes, was undone if judges were used to bludgeon workers too directly?footnote11

8. Entry into the eec, approved in 1972 only by the narrowest of margins in the Commons (a majority of eight, dependent on right-wing Labour votes), provoked heated debate in Britain, to which nlr devoted a special number that set out a position which distinguished the journal starkly at the time. In the most sustained single reflection of the period on the issues posed by the Common Market, ‘The Left against Europe?’ took issue with a broad span of liberal and left thinkers—Leavis and Williams were among the culprits—and virtually every revolutionary group of the period. The Common Market, the essay argued, should be regarded in the way Marx and Engels had viewed the agricultural and industrial revolutions, or free trade: as a progressive bourgeois advance that for all its historical costs offered better ground on which the left could fight its historic adversary. The Conservatives had put (their) class before nation in backing entry, whereas Labour and the left at large were betraying (their) class to the nation in opposing it. ‘The one thing with which no socialist could conceive of reproaching Heath is “dividing the nation”. For unless the proletariat sets out to divide the nation more, to the utmost, it is lost. It has to put class before nation always, and class against nation where necessary.’footnote12

9. In Scotland, on the other hand, where the snp had won another by-election, nationalism in ‘North Britain’ was treated in a quite different register. The anomaly of Scottish nationalism’s hesitant, belated emergence in the 20th century was a consequence of the exceptional bargain the country’s dominant class had made with Hanoverian England in the 18th century. That pact had given it membership rights in the world’s premier empire and first industrial revolution, rendering a separate state unnecessary for entry into modernity, as it was not anywhere else in Europe. Within another year, these reflections had developed into a full-blown historical theory of nationalism as a global phenomenon in ‘The Modern Janus’. Constitutively at once progressive and regressive, product of capitalism’s uneven development across the world and the need for successive breakwaters against it, nationalism had been the area of Marxism’s greatest—theoretical and political—failure of historical understanding.footnote13

Wilson–Callaghan

10. The downfall of Heath came at the hands of the miners in 1974, when he called an election for a mandate to deal with them and lost it, the only time in post-war Europe that collective action by workers detonated the overthrow of a government.footnote14 Returned to power through no merit of its own, Labour spent the next five years to as little avail as its predecessor. Amid continuing industrial turbulence and economic crisis, first Wilson then Callaghan made desperate bids to brigade the unions into a concordat enforcing wage restraint. By now, however, the change in the global conjuncture of capital, as the long downturn set in, had created such acute stagflation in Britain that workers could not be policed from above. Labour’s vain endeavours to do so, culminating in another foreign-exchange crisis, another international rescue package, this time with draconian conditions from the imf, led to another wave of strikes in the Winter of Discontent of 1978–79. Thereafter, having ditched its promise of devolution to Scotland, torpedoed by its own mps, Labour met retribution from peripheral nationalism, the snp felling it in a vote of confidence in the Commons.

11. In these years, as the general crisis of the established order deepened, the journal returned to the longue durée that lay behind it. Fault-lines now becoming visible followed from the original composite nature of the British state itself. Uniting three disparate realms in the fashion of many dynastic assemblages of the early modern period, the very success of the Anglo-British parliamentary monarchy in overtaking all rivals to become, as early as the 1690s, the most advanced power of Europe, fixed it fast in a shape whose counterparts elsewhere were later swept away. Developmental priority and imperial success had arrested the British ancien régime—‘the grandfather of the contemporary political world’— half-way between feudal and modern forms, leaving its structures an ‘indefensible and unadaptable survival’ of the transition from absolutism to constitutionalism.footnote15 Its famous mastery of the arts of political absorption and social integration, averting any equivalent of the second round of bourgeois revolutions that occurred in other major capitalist countries, had incapacitated the ensuing system for the tasks of economic modernization. Entry into the eec had come too late to affect its fortunes.

As it floundered, secession threatened to eclipse even class conflict in breaking it apart. Peripheral nationalism, though less powerful and significant than international or social pressures on the existing order, appeared now more likely to precipitate conflict within it. In such conditions, against a receding horizon of socialism, the left would have to revise its view of nationalism. There was still a distinction to be made between nationalist and socialist revolutions, and an order of inter-relations and priorities among them. But these had become more nuanced and analytically demanding than of old, though Lenin’s instinct that the former could in given circumstances form a vital detour towards the latter might prove applicable in the case of Britain.

12. Such were conjectures of 1977. Two years later, on the eve of the Conservative victory of May 1979, an alternative scenario loomed larger. Were the British system of power to crack at the centre rather than the periphery, the break was more likely to come from the right rather than the left. The traditional emergency formula of a cross-party National Government might loom ahead, even if one of the previous conditions of this standby of 1916 and 1940–45 was missing—‘there will never be another imperial war’—and it could now prove only a temporary palliative. A more radical rupture with the status quo was gestating among strata traditionally marginalized and treated with patrician condescension by the establishment. In opposition, this was the direction in which the Conservative party under Thatcher was moving, the ‘truculent skeleton of laissez-faire’ leaping from its coffin.footnote16

Thatcher–Major

13. Thatcher in power, a much longer essay, ‘Into Political Emergency’, appeared as a postscript to the second edition of The Break-Up of Britain in 1981.footnote17 This brought together in a single compass themes nowhere else so pointedly inter-connected in the journal’s writing on the uk. For over a generation, socialists had endured ‘a wasting British world where no break gave relief’, as socio-economic crisis persisted under one unavailing government after another, while the established political system had seemed more stable than ever. They had looked first to working-class insurgency for a rupture in this order; then to an alliance of students and workers for a combined revolt against it; and finally at the possibility of peripheral nationalism bringing it down. But though not all was illusion in these successive ‘ideological exits’—the first had overthrown Heath, the second had given birth to a less conformist intellectual class, the last had toppled Callaghan—none had struck at the central nervous system of power in Britain.

That lay in the Westminster state and its long-term strategy of economic survival. Imperial expansion had formed this state. When that was no longer available, it followed its traditional outward bent, resolving to ‘press towards the internationalization of the uk economy as the answer doing most good to the flourishing parts of the system and the least damage to the ailing ones’. The civil elite of the state had long ensured that this strategy of ‘eversion’, turning outwards, was consensual among political parties. Out of it had grown the gulf between a prosperous, rentier-financial South and a relegated-industrial North already depicted by Hobson—the larger structural division within which the respective plights of Scotland, Wales and Ulster were lodged. Though rational enough as a grand design of the traditional order, the logic of such eversion was essentially unavowable. ‘A national state formation cannot openly embrace a goal which, by obvious implication, undermines and discredits its own separate existence and power.’ So while perfectly sound as a strategy, it was ‘so unpalatable to so many as to be unsellable’. There was no way of turning its aims into effective political interpellations.

14. Since taking office, Thatcher’s one genuinely radical act had been to take this long-term, underlying trajectory of the state a step further, by abolishing all exchange controls. With this bonanza for the City, the prospect in view was that ‘the metropolitan heartland complex will become ever more of a service-zone to international capital’, while ‘the industries and populations of the Northern river valleys will eventually be shut down or sold off’ as assembly-stages or branch-units of American, German or Japanese corporations. Too direct a conflict with the working class could still be avoided, given the temporary cushion of North Sea oil—the monetarist belligerence of the government did not necessarily spell any all-out confrontation with the unions. In face of the miners, Thatcher too had so far retreated, in yet another episode of the phoney war between capital and labour in Britain, any dénouement indefinitely delayed. What of the forces of contestation? Scottish and Welsh nationalism had moved to the left, and contrary to earlier predictions, the outlines of an English nationalism not inherently reactionary could be glimpsed in the Alternative Economic Strategy (aes) advocated by Benn, since the opportunities for progress in the eec had proved less than once believed. Still, the aes contained the obvious danger of a Jacobin centralization blind to the realities of peripheral nationalism. Only if that were overcome, could an English socialism put behind it the ‘shame and defeat of British socialism’.

15. In the event, assumptions of a continuing social stalemate at home and impossibility of imperial war abroad were no sooner expressed than confounded. Within six months of ‘Into Political Emergency’, Britain was at war with Argentina over its colony in the Falkland Islands; and in its after-swell a dénouement of the war between capital and labour would not be long delayed, triumph in the South Atlantic paving the way for victory in Yorkshire. The special issue of nlr on the Falklands—like that on Europe, a full-length essay later published as a book by Penguin—opened by observing that the old saw that history repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as farce, needed to be updated: in a repeat of a repeat, this time not as farce, but now in the television age as spectacle, elevating Thatcher to a war leader of the nation in three hours of overwrought debate in the Commons in which every party offered her support for a naval expedition to recapture the colony.footnote18 The journal had never paid much attention to proceedings in the Palace of Westminster, for all their role in the ‘central nervous system’ of power in Britain. Now it loosed a scathing analysis of the all-party jingoism that had sent the fleet into battle, allowing Thatcher to hail ‘the spirit of the South Atlantic’ in which the country fought to recover its lost possession as the ‘real spirit’ of Britain, proof that it ‘has ceased to be a nation in retreat’. What enabled this paroxysm of unity was the enduring matrix of the Churchillian legend of a people in its hour of trial closing ranks behind a heroic chief. Still living in the mind of the parties that had joined together in the victorious coalition of 1940–45, this was the epic scene reenacted in all absurdity in 1982. That without loss of life, and for a fraction of the cost of the expedition to the Falklands, the tiny island population could have been relocated with munificent compensation to New Zealand or elsewhere—Britain had without compunction or compensation removed the population of Diego García to make way for an American air-base—was publicly unthinkable.

16. A year later Thatcher’s re-election in 1983 with a sweeping parliamentary majority, could not be minimized. Taking stock of it, an editorial in the journal, while pointing out the limited size of the vote that had given her a second mandate, did not understate the depth of Labour’s defeat.footnote19 The fiasco of Wilson’s ‘modernization’, the debacle of Callaghan’s corporatism, not to speak of the abjection of Foot’s jingoism, had left the working class divided and demoralized, and the party with a mere fifth of the electorate. Thatcher, by contrast, had staged an intra-party coup, routing Tory paternalism as well as Labour corporatism with a cult of the market and a petty-bourgeois zeal no longer restrained by fear of the proletariat. This was not a radical liquidation of the old order. But nor was it a mere sentimental mystification. In offering the masses, from its base in the South-East, the City and the informal economy, hope of new jobs, control of inflation and the promise of information technology, Thatcherism appealed with notable effect to the popular sensibility of what Raymond Williams, in the leading article of the same issue, termed ‘mobile privatization’.

17. But would Thatcher succeed in reversing the economic descent whose fall-out had brought her to power? In 1987 a reprise of nlr’s original problematic measured its characterization of the ruling bloc in Britain and the relation of it to the country’s decline against the historiographic evidence that had accumulated since.footnote20 Arno Mayer’s Persistence of the Old Regime had shown that continuing aristocratic power was the rule, rather than the exception, in Europe down to the First World War. Where did that leave the landed class in Britain among its peers? Sufficiently specified, still a case apart: the wealthiest, most stable and most exclusive of the set, enjoying higher productivity on its estates, greater expanses of urban property and mineral resources, and far longer experience of rule in a parliamentary system. Conversely, British manufacturers were economically much smaller figures than the industrial magnates of Pennsylvania or the Ruhr; and while the City might be the capital of world finance, Britain never knew the world of finance capital emergent in the us and Germany, as depicted by Hilferding. British Labour, for its part, had nothing to show for its spells in office between the wars, compared with German or Austrian constitution-making, French vacations or Swedish public works, and when in 1945 it gained the largest parliamentary majority of any post-war social-democracy, left the general configuration of British capital and state untouched. Unlike any of its major competitors, the country knew no second revolution from above after the settlement of 1689, nor intervening convulsion on the road to modernity. After the Attlee government, alternating Conservative and Labour sequels from Churchill to Callaghan had each proved incapable of reversing post-war economic decline.

18. How far had Thatcher’s regime, with its integrated package of labour discipline, state retrenchment and financial decontrol, succeeded where they failed? After its deathblow in 1985 to the miners, deserted by Labour and the tuc, the unions were broken.footnote21 Both productivity and profitability in industry had improved, though still lagging well below competitors abroad. But the international position of uk manufacturing had steadily worsened, Britain becoming for the first time in its history a net importer of industrial goods. Markets were not self-redressing: centralized direction of one kind or another was needed to correct them. But of the four variants at work elsewhere—dirigiste planning in France, industrial banks in Germany, state-keiretsu coordination in Japan, corporatist concertation in Austria or Sweden—the necessary social agents were all lacking in Britain: neither its bureaucracy, nor its finance, nor its labour movement was equipped for the task. Did that matter? Or did the remorselessly uneven development of global capitalism, and over-competition within it, mean that the British fate might be becoming more general?

19. More systematically comparative than the initial theses in nlr, and a more detailed and documented exposition of them, this was a narrative that accorded far more space to the ruling bloc than to either the intelligentsia or labour. Two subsequent texts sought to make good these lacunae. The first, written in the last year of Thatcher’s government, looked at what had become of the intellectual landscape surveyed since the sixties.footnote22 There, it concluded, a major reversal had occurred, change in the eighties moving in the opposite direction to that of government, in good measure because of the animus of Thatcherism against the universities. But it was also because the boundaries of intellectual life had altered, as—in part because of the generational upheaval of the sixties—European currents of thought now percolated through it on one side and American on the other, eroding the philistine provincialism of the post-war matrix. The result was not just to loosen the grip of the ‘vacantly asocial and slackly psychologistic’ pattern of old, fostering more historical and international ways of thinking, but to weaken the conformism associated with it, including the unthinking male chauvinism of the past, contested by a renewed feminism. While remaining generally liberal within centrist parameters, the political outlook of the intelligentsia had undergone a certain radicalization,footnote23 hostility to Thatcher becoming widespread, a trajectory exemplified in what had become its most representative periodical, the London Review of Books. A marked disjuncture had opened up between high politics and high culture, familiar enough on the Continent, hitherto unknown in Britain.

20. What of Labourism? Its condition was set, first within the transformation of the social and political landscape of the country effected by Thatcher, which rather than any fundamental economic change was her real legacy. There her greatest achievement was the ideological adaptation of the Labour Party to her rule, a make-over confining its aims—this was still prior to Blair—to no more than a mild softening of the impact of a neo-liberal regime.footnote24 Secondly, it should be seen within the framework of its sister parties in the Socialist International. There, once the long downturn of the global economy set in, welfare systems and full employment coming under pressure, social-democracy lost ground everywhere in Northern Europe, and gained it in Southern Europe only by exchanging these for liberal or secular reforms of no particular social connotation. Did that mean Europe was gradually moving towards the pattern of America or Japan, without any social-democracy at all? In Britain, Labour had followed the general parabola of its North European sister parties, if with fewer members, weaker regional substructures, lesser command of proletarian loyalties, and scarcely any academic or media supports.

21. Faced with the same fog of political uncertainty as the rest, Labour was confronted in addition with the problems of national decline, which it could not comfort itself were simply those of the chronological priority of Britain as a first-comer to the industrial revolution, since Belgium showed that with the same handicap and its consequences, decline could be reversed. But for that, concertation of some kind was required, typically at the initiative of the executive. In Britain, however, the structure of the legislature, based on an unwritten constitution and a voting system long pre-dating the arrival of democracy, compounded by the structure of Labour—still less democratic than the state itself—precluded the relatively more equitable representation of forces on which effective concertation of capitalism alone could rest. Proportional representation, an intellectual product of the revolutions of 1789 and 1848 in Europe—its pioneers, Condorcet and Considerant—was the only acceptable formula of democratic choice, and the constitutional-reform campaign Charter 88 was right to champion it as the principle of a political reconstruction of the state. The social citizenship theorized by Marshall could only acquire full meaning if the political citizenship he thought had preceded it, but in any true sense had not, at last took hold in the land of first-past-the-post.

Blair–Brown

22. With the arrival of New Labour in 1997, this remained the prism through which in the first instance it was judged. Three years into the Blair regime, what was the record?footnote25 Against the background of a strong currency and business support, steps to quell unrest in the periphery had been carried through smoothly enough: measures of devolution granted to Scotland and Wales, and pacification achieved in Ulster. But amid a whirl of modish slogans and futurist postures, the mainframe of the British state system had remained sacrosanct. So far as any democratic principle went, proportional representation had been consigned to the Greek calends, the House of Lords merely altered from a vivarium of birth to one of patronage. Constitutionally speaking Blairism, vaunting its strong hand, offered a simulation of the caste-power of the old order and last-ditch Britishness. Beneath its posturing lay the country that had not spoken yet, the English, whose voice had long been usurped by a British-imperial class speaking for them. In not affording it any institutional expression, Blair’s project made it likely that Powell’s intonation of it would be heard once more—that ‘England will return on the street corner, rather than via a maternity room with appropriate care and facilities. Croaking tabloids, saloon-bar resentment and backbench populism are likely to attend the birth and have their say. Democracy is constitutional or nothing. Without a systematic form, its ugly cousins will be tempted to move in and demand their rights.’

23. But how far could the path from Thatcher to Blair be reduced to the dynamic of Ukanian constitutional devolution or involution? What such a depiction risked was a conceptual landscape of Britain swept clean of all but ‘one significant life-form and one technology: the post-1688 ruling bloc and its prosthesis, the Westminster state’—apart from peripheral nationalism, their potential nemesis.footnote26 In such a contrast, full historical agency was granted only to state-elites and peoples-as-nations. In any vision in which the fate of modernity came down simply to nationality, other manifestations of solidarity or antagonism, above all class relations, could only be relegated to a secondary, intermittent existence. Yet ‘any appeal to nationality is always a coded declaration for, or against, a substantive social state of affairs’, and if constitutionalism were to become the passe-partout of analysis of Ukania, it would have nothing to say even about the social order of an independent Scotland, leaving what actual constitution it should adopt a blank. But politics was a matter of policies as well of charters, and high-minded indifference to the former, as if a budget could not in its own way be as synoptic of a society as a constitution, might come at a political price, leaving in place ‘a refurbished social-liberal hegemony for an unalterably capitalist society’. The struggle to foster a popular left alternative to Blairism might be the low road to the constitutional sublime, but if the critical test of New Labour were to become the pragmatic success or failure of its management of capitalism in Britain, it could prove the only one available.

24. On the eve of the 2001 election, verdicts on the trajectory of Ukania could be updated. Thatcherism had wrought many real changes to the country, but the restoration of grandeur was not among them.footnote27 The stability of the old order had rested on the external force-field of empire; once that was gone, the patriciate lost its grip at home, deference giving way to a ‘molecular, resentful sort of rebelliousness’, disabling the supports of the old regime, and Thatcher’s lower-middle-class crusade could finish off the grandees. After her fall had come the miasmic torpor of Major’s half-decade, then Blair’s nebulous concoction of Enterprise Culture seasoned with the remains of Welfarism. It was a mistake, however, to attribute the ensuing pathologies just to the effects of neo-liberalism. For these were inseparable from futile attempts at retrieving national greatness, in which the very term ‘decline’ was a lure inviting the notion that ‘revival’ was possible—changing everything not so that they remained the same, Lampedusa-style, but so that they would become immensely, improbably better. The forces of British retro-nationalism still had plenty of assets in their fight against the prospect of a liberated archipelago—cadres of the state, much of the intelligentsia, most of the media. Immigrant politicians from Scotland like Brown were among these, servitors of the City and transplants of great-nationalism. But the parabola of Blairism could be predicted. The rules of the system prescribed a concluding Majorite phase of bedraggled sleaze and exhaustion, before eventually, ‘eviction into the frozen wasteland of disgrace and ridicule in its turn’.

25. In 2005 disgrace and ridicule were yet to come. Blair was still in charge of managing British capitalism and there was little sign of popular resistance to his regime, which had consolidated the paradigm set in place by Thatcherism.footnote28 The economic recovery staged by Major after Black Wednesday had been husbanded with a continuing credit and consumer boom, still with low rates of investment and weak productivity growth. Overall income inequality had not been reduced, while wage differentials and the gender gap were widening. Increased public expenditure on health had failed to match European levels, service in hospitals and schools deteriorating. Partial democratization in the periphery—limited devolution in Scotland, less in Wales, pacification in Northern Ireland—had been accompanied by increased authoritarianism at the centre: Blair side-lining his Cabinet and Blunkett stepping up police and legal repression. Abroad, New Labour had distinguished itself as the most aggressive adjutant of American imperialism in post-war history, its eager accomplice and subordinate in Washington’s wars in the Balkans, Afghanistan and Iraq.

Greeted at the outset with euphoria by the intelligentsia, and unprecedented fawning in the media on Blair himself, New Labour had not gained any deep adhesion among the masses. Re-election in 2001 had been secured on a low share of a low turn-out. But with the Conservatives in disarray, New Labour had become the preferred option of British business, as more European than the Tories and better at presiding over deregulation and domesticating the unions. For capital at large, neo-labourism was a satisfactory second round of neo-liberalism, somewhat more flexible and emollient than the first. For the Thatcher-averse intelligentsia, even if by now somewhat crestfallen over Iraq, New Labour was still the lesser evil; while for sections of the sentimental or sectarian left, it remained the party of the working class, and ‘the slumbering soul of True Labour’ would eventually awaken.

26. The upshot was that the sway of New Labour over the Ukanian political landscape was a hegemony that was strangely weightless, more negative than positive, lacking any novel ideological interpellation other than the ephemeral vacuities of the Third Way. Resting largely on the absence of any effective opposition from the ranks of a divided Conservatism, it had not produced any cadre of passionate followers or transformation of popular sensibility of the kind which ensured that Thatcher’s hegemony left a much deeper imprint on the country. In this limbo, the Economist had decided Blair was the best right-wing prime minister Britain could have, sufficient reason for the left to find any other preferable. What principally distinguished New Labour from its predecessors, going back to the 1950s, was the number of deaths for which it was responsible abroad. The sooner it fell, the better.

27. What of the Conservatives, after a dozen years in opposition? The old governing class, in which a landed aristocracy had—without disappearing—metamorphosed into the figure of the upper-class English gentleman, seconded by a stratum of haut-bourgeois professionals, had come to its end with the defeat of Home in 1964.footnote29 Sociological changes—a better educated, less deprived working class and an expanded middle class—had undermined the traditional hierarchies on which this stratum rested at home, while abroad the empire from which it drew its ultimate claim to power and calling had dissolved. This was a double blow, propelling lower-middle-class strivers, first Heath and then Thatcher, into leadership of the Tory party, each of them more combative in fighting the battles of capital against labour and radical in seeking solutions to economic decline. The first failed to break the unions or revive the economy, but succeeded in taking Britain into Europe as a surrogate for Empire. The second crushed the unions and, mauling many old-guard institutions in the process, injected more energy into the economy, if without altering its direction. But in turning a petty-bourgeois nationalism against Europe, Thatcher eventually split the Conservatives, driving them into the wilderness for a decade.

New Labour, bent into shape by Thatcherism, had hewed without compunction to its neo-liberal domestic agenda. But unencumbered by reflexes of national sovereignty that still twitched in the imperial-conservative unconscious, it was happy to play its part in the European Union, and happier still to serve as all-purpose equerry for the United States. Culturally too, it could go one better than Thatcherism by ditching Victorian values for just-in-time helpings of Diana kitsch and Cool Britannia. In face of this mutant heir to its former heroine, the Tories—after three successive zeroes from the lower ranks: products of a comprehensive, a secondary modern and a grammar school—had now finally reverted to form and picked an Etonian to lead them. But Cameron, like his colleague Osborne, though of impeccably upper-class background, was indistinguishable in tastes, outlook and religiosity from Blair, on whom he openly modelled himself: all were friends of Berlusconi. His leadership was a faux restoration. Tory England in the old sense was dead. What had replaced it in the Conservative Party was not better.

28. On the eve of the election of 2010 that would finally propel New Labour into a frozen wasteland, by now overdue, the books on its record could be closed. From 1997 to 2008 it had presided over a boom fuelled by an asset-price bubble, which the global financial crash brought to an abrupt end.footnote30 Under Blair and Brown, the share of finance in the economy had grown more sharply than in the us, that of manufacturing dropped more steeply than under the Conservatives. Mortgage debt per capita was higher than in America, and inequalities of income and wealth had only increased. A fifth of public spending was now sub-contracted to the private sector; 90 per cent of capital expenditure in health. In higher education, quant-mania had gone a pathological step further with the Research Excellence Framework (ref). In the name of the War on Terror, repressive legislation had intensified and numbers incarcerated risen. Constitutionally, pacification of Ulster, and devolution in Scotland and Wales, however limited or grudging, were advances. But against them had to be set corrupt remodelling of the Lords, and grotesque levels of sleaze in the Commons. In foreign policy, Labour’s traditional Atlanticism had taken on a new twist, a hyper-subalternity to the us in an era when America had become the sole super-power, whose pay-off overseas was a hugely greater sum of killing and torture than under Macmillan, Thatcher or Major: alone reason enough for New Labour to be thrown out of office.

Cameron–May

29. Analysis of the results of the 2010 election showed that it was the scale of the desertion of Labour by the working class, especially in regions of high unemployment, which gave the Tories their qualified victory with no more than 36 per cent of the vote.footnote31 Lacking a parliamentary majority, Cameron was swiftly shoe-horned by the civil service into a coalition with the Liberal Democrats, nominally less conservative than the Tories. But there could be little doubt that austerity, predictable enough already under Brown, would be harsh under the coalition. How far would that alter the prospects for Labour? ‘Opposition to Tory cuts may not be enough to return New Labour to government, but it could help to sustain what might be called Corbynism, after the member for Islington North: niche socialist activism of an honest and sometimes effective kind’, but yielding nothing but a parliamentary seat here or there and renewal of the traditional belief on the left that one day the party would be made afresh. Viewed comparatively, the post-crash politics of the West showed tactical adjustment of its bipartisan consensus by the centrist parties, but little change of outlook. The widely proclaimed end of neo-liberalism looked more and more like the continuation of its agenda by other means.

30. In 2015, Cameron was returned to office without need of the Liberal Democrats, who were decimated at the polls, and in the wake of Labour’s renewed defeat, Corbyn was elected its leader in the first one-person-one-vote election in the party’s history. Within a year came the referendum, called and lost by Cameron on Britain’s membership of the eu.footnote32 His decision to call one, product of long-standing divisions among the Tories, was designed to silence the Eurosceptic wing of his party, in a careless display of class insouciance that with united establishment support—extending from the City to the tuc, not to speak of all-party backing—victory was assured. But as in France and the Netherlands, a popular rebellion against the whole governing class led to the opposite outcome. Two thirds of the working class voted for Leave, a higher proportion than any stratum—including even the best-off—voting for Remain, on a larger turn-out than seen in years. London, beneficiary of the financial bubble and closer to Paris than Manchester by rail, voted heavily for Remain; the abandoned industrial North, hardest-hit by austerity, heavily for Leave. On the left, opinions had divided. Those in favour of Remain argued that the xenophobia of Brexiteers of the right made the eu a lesser evil, those in favour of Leave that departure would be a blow to the neo-liberal oligarchies on both sides of the Channel: each voting negatively against, rather than for, anything. But what would Brexit actually mean for the European Union, or for Ukania in parting with it? So far, all that was clear was that ‘Blairized Britain has taken a hit, as has the Hayekianized eu’ and ‘critics of the neoliberal order have no reason to regret these knocks to it’, against which the entire global establishment had inveighed.

31. More fine-grained analysis made clear the extent to which the Brexit result, though certainly multi-stranded in motivation, was the expression of a regional and social revolt in the North of England: Leave majorities were concentrated in former strongholds of Labour, now reduced to a hinterland of decayed industries and discarded proletarian households.footnote33 There was hostility to immigrants in this part of the country, as elsewhere in Britain. However, that it was not the primary driver of the outcome could be deduced from Labour’s unexpected recovery in the election of 2017, once Corbyn campaigned on a platform amounting to a rejection of the whole neo-liberal order in place since the 1980s. In the face of a high Tory vote, he not only held most of the North, but swept the youth of the country by margins never previously approached by Labour, in what was now a second popular uprising against the entire British establishment. Yet Corbyn’s position remained tenuous in his own party, whose permanent apparatus and parliamentary delegation remained ferociously opposed to him.footnote34 The small team around him lacked any preparation for government in what would be the predictable conditions of an implacable siege by capital and the media. There were no grounds for euphoria.

Resumption

32. Looking back, how might the balance-sheet of this record be read? On the credit side, nlr pioneered critical analysis of half a dozen aspects of British political life that continue to shape events, and was on the whole prescient about them. These were: (i) the historical nature of the ruling bloc; (ii) the deep structures of Labourism as a phenomenon specific to Britain, up to the early 1990s; (iii) the distinctive patterns of post-war intellectual culture, and some of the changes in them; (iv) the eversive form of Ukanian economic development, and its effects on class and region across the country; (v) the eruption of peripheral nationalism, above all in Scotland, as a symptom of the decline of the composite, imperial Anglo-British state, and the tensions and risks of racism in a subcutaneous English identity within it; (vi) the fissiparous impact of Europe on British politics, dividing left and right alike.

33. On the debit side, the ideas and arguments of this body of writing had, each of them, significant omissions or limitations. So far as the first of these went, although it conformed in many ways to the journal’s original diagnosis of the metamorphosis the dominant bloc would have to undergo to remain hegemonic, there was a missing element in its analysis of the watershed in Conservative evolution represented by Thatcherism. Focussing on the social shift in the party’s leadership, the economic logic of its direction, and the political engineering of its electoral base, despite a preliminary intimation it neglected the specific ideological grip that Thatcherism acquired over active supporters and ostensible opponents alike, not to speak of passive acceptance. Understanding the forms and mechanisms of this sway was the great achievement of Stuart Hall, in the pages of Marxism Today. So too, though nlr predicted, even before Wilson came to power in 1964, the contradictions that would in time wrench the combination of party and unions that constituted Labourism apart, and tracked these thereafter, it failed to register the extent of the changes in the country’s working class that would become a condition of Blairism. There it was Eric Hobsbawm who saw much earlier and more clearly what was happening, well before New Labour. nlr published both Hall and Hobsbawm, in its imprint and its journal, and critiques of each by others on the Left, without itself engaging them.footnote35

34. Treatment of the intellectual landscape of the country, however ambitious in intention or pugnacious in detail, was wanting in two respects. From the start, insufficient attention was paid to the importance of liberalism, in its variations—economic, political and social—from Victorian times onwards, as a circumambient ether in the mental world of the established order, as it remains today. The links, or lack of them, between selected intellectuals and high politics was another gap in the journal’s coverage; the importance of these in Thatcher’s rule was overlooked, even though with eminences famously external in origin supplying the theoretical compass of her system, earlier verdicts on the post-war intelligentsia were confirmed. In the same period, the radicalization of macro-economic eversion, delineated starkly enough as a further stage in a long-standing process at national level, set the world-wide arrival of the neo-liberal paradigm—signalled by Mike Davis in 1984footnote36—only in passing rather than with the needed force, in the international regime-change of the time.

35. If Scotland and Europe were each emergent cruces in the trajectory of Ukania from the late sixties to the present, where the Review (though it had little to say about Ireland after 1969) was analytically well ahead of contemporary registration of them, they also formed areas of its thinking where early insights were never stabilized into an integrated conception, with subsequent interventions subject to oscillation and division. Tom Nairn foresaw, when it was still scarcely visible, the take-off of Scottish nationalism, captured its historical exceptional forms and conditions in a set of portraits that scintillate to this day, and developed out of them one of the commanding general theories of nationalism of all time. But as the title of The Break-Up of Britain, question-mark declined, would indicate, the coming of an independent Scotland was held too certain.Between prevision and consummation there would be so protracted a delay that in the interim, the original connection between nationalism and socialism in this prospect slipped, hopes in the former eclipsing conceptions of the latter, as Francis Mulhern would point out. One result was that coverage of New Labour in the journal tended to decant analysis of its constitutional and its socio-economic records into separate, successive analyses rather than connecting them in a unified field.

36. In the case of Europe, too, first takes were each in their way clairvoyant. Robin Blackburn’s judgement of 1971 that entry into the eec was ‘bound to shake many of the pillars of bourgeois Britain’, threatening institutional legitimations of the status quo and sowing discord in the ranks of its defenders, would be confirmed in due course with a vengeance. Tom Nairn’s essay of 1972 remains unmatched, half a century later, for depth of historical reflection on the issues posed for the left by the form that European unity had taken with the creation of the Common Market—nothing approaching it having ever appeared on the continent itself, let alone when the same questions were reopened in Britain in and after 2016. The categorical affirmation with which it concluded could not, as the Community later unfolded, remain so unqualified. In 1976, contesting a Norwegian vision that projected the eec as a future super-power, Nairn observed that this it would never be, because, as with the multi-national empires of the pre-1914 era, any such prospect would be undone by the uneven development of capitalism that had everywhere generated nationalism as a breakwater against it. In the eec, however, the strengthening of a cross-border capitalism was bound to aggravate uneven development between its regions, weakening the authority of the old nation-states without putting anything as effective in their place. Thus a ‘purely economic reinforcement of capitalism does not entail a corresponding reinforcement of bourgeois power in the crucial state-ideological sense’—a contradiction the left should seize upon. Looking back, another four years on, ‘The Left against Europe?’ had gone too far, in a stance implying an ultra-Europeanism that disconcertingly, if tangentially, echoed the outward drive of the rulers of the country. Overestimating the genuine but limited possibilities opened up for the left by entry, it had overlooked the extent to which, for the right, ‘“Europe” was a humble predecessor of the monetarist runes of post-1979.’footnote37 As runes became reality after Maastricht, and in one trenchant verdict after another, the journal took systematic stock of the political and economic dynamic of the Union it created, little was left of the prospect of 1972.footnote38

ii. outcomes

What bearing does the record of past nlr writing on Britain have on the present? Perhaps never before has what would be a distinctive problematic of the journal been so vividly concentrated in a single conjuncture as that of the past few years. To all appearances, what Britain has been witnessing are: (i) a sudden recomposition of the dominant political stratum; (ii) a decomposition of the traditional Labourist pendant to it; (iii) the explosive dénouement of long-standing conflicts over Europe; (iv) widespread intimations in the media, not so much of competitive decline, but of suicidal self-harm and proximate socio-economic disaster; (v) clamorous dismay in the intelligentsia; (vi) mounting pressure for secession in Scotland. In other words, closely intertwined, simultaneous crises of class, state and nation. Though on the surface, continuity between the original problematic of the Review and current circumstances may look striking enough, the analytic relevance in concreto of past findings cannot be assumed. They have to be tested against the novel particulars of the situation.

There is a preliminary question. The original nlr approach was totalizing: taking the principal structures and features of British society as an integrated complex which it was the object of analysis to capture, in keeping with the injunctions of Lukács and Gramsci. How far does this aim still make sense, in a period where nation-states, permeated or overborne in every direction by transnational market and media forces (not to speak of geo-political pressures) external to them, have ceased to be—even approximately—closed totalities? In the 1980s, something like a parallel enquiry got under way in the journal on the United States, a much larger and more complicated society, in the work of Mike Davis. Prompted by nlr’s approach to Britain, a country observed by him first-hand at the time, this body of writing on America—encompassing not only the working class, the middle class and the exploiting class, but the national and imperial, economic and electoral, cultural and political, demographic and ecological scenery of the United States—would in time expand far beyond what had been attempted in the uk, and in doing so, to the encompassing world beyond America itself.footnote39 Has anything like this, however much more limited in scope, been generated in another country since? Yet, whether or not they continue to form totalities as bounded as formerly, the societies over which nation-states preside unquestionably still represent determinate strategic horizons of political action for those who live within them, and for practical purposes remain in that sense as germane as ever.

Inter-connected with this question is another, bearing no less directly on the problematic of the journal set out in the sixties, one already raised before mid-point in the subsequent years. How far did ‘decline’, as an organizing framework for analysis of developments in Britain, lose its purchase on them once ‘globalization’ arrived, in the shape of a common deceleration of growth and acceleration of financialization across the advanced capitalist world, with the liberation of capital markets, extension of supply chains and generalization of neo-liberal regimes that set in during the eighties?footnote40 Could it be said, in Sartre’s terminology, that a double detotalization—of both unit and path of analysis—has since overtaken the particular line of enquiry pursued by the journal?footnote41 The answer can only lie in the actual record of the economy, viewed comparatively, and of the agency of the state that has presided over it. The journal’s propositions were not confined to these, but in seeing how far they retain contemporary relevance, the economy is a starting-point.

1. Decline

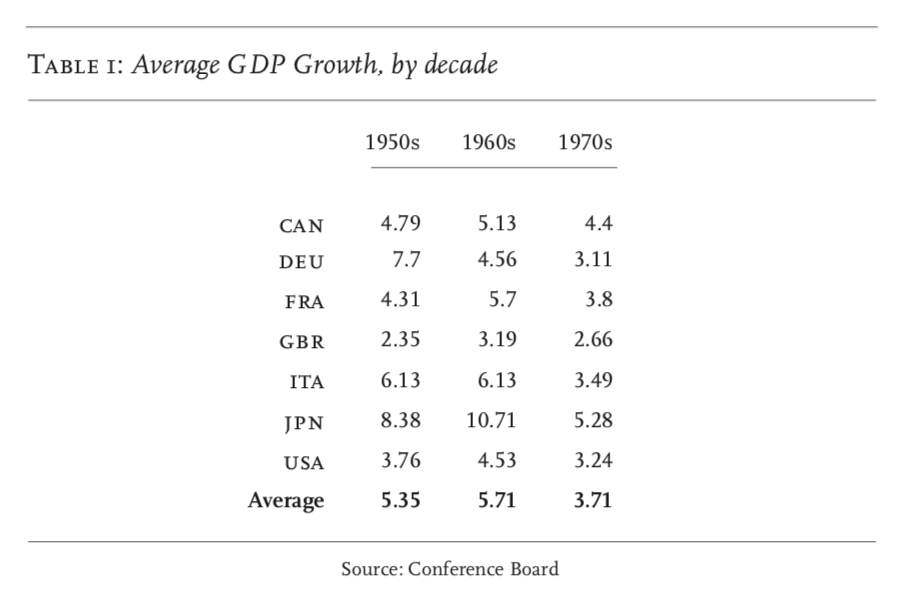

The deterioration in the country’s position which first attracted widespread debate in the sixties was always relative to that of its peers, never absolute, as growth lifted living standards over the next half century. Between the fall of the Attlee and the fall of the Callaghan governments, there could be little doubt of Britain’s loss of competitive ranking, as the table below of performance in what would become the g7 states makes clear. Across three decades, Britain regularly came bottom of the group:

This was the pattern that Thatcher’s regime set out to break with a completely new orientation, which in due course, it boasted, had led to an economic renaissance of the country; a term reiterated by New Labour when it came to power, claiming to have abolished the business cycle and be setting an example to Europe in the dynamism of Britain’s market economy. Historically, how well do these claims stand up?

The most authoritative case for the success of Thatcherism is made by Nicholas Crafts, for whom its three great achievements were to break the obstructive power of the unions, to lower tariffs, and by deregulating markets and privatizing public monopolies, to unleash competition. In doing so, Crafts argues, it reaped the benefits of information and communications technology (ict), a general purpose advance to which the more decentralized economic system it created would prove better adapted than its dirigiste predecessor had been to mass production Fordism in the post-war period, even if it essentially presided over technological diffusion rather than innovation. Thatcher’s overhaul of the economy was incomplete, since it left the separation between ownership and management of enterprises, a long-standing bane in Britain, untouched. But the balance-sheet was unquestionably positive. The country no longer lagged behind France and Germany, as it had before.footnote42

What of productivity in these years? If overall gains were not much above the European average, in manufacturing there was a marked improvement, rising by 4.7 per cent a year between 1979 and 1989, while profits had jumped 44 per cent by the end of the decade. But, as Andrew Glyn showed, over half of the productivity gains came from shedding labour, while investment in manufacturing underwent a spectacular reversal, as its profits were diverted into financial and business services, where investment leapt 320 per cent during years when investment in manufacturing inched forward barely 13 per cent.footnote43 By 1991, manufacturing output had risen just 6 per cent, compared with an oecd average of 35 per cent, crawling across the whole period from 1973 to 2007 at an annual average of no more than 0.4 per cent.footnote44 Overall, between 1979 and 1990, gdp grew 2.3 per cent a year, below the 3 per cent rate from 1949 to 1973.footnote45 Investment in r & d was not only well below competitors, but actually fell in the last thirty years of the century.footnote46

With Thatcher’s arrival in power, the imposition of a sharp deflation to switch the country across to a new economic regime led to a severe initial recession in 1980–81, and continuing high rates of unemployment thereafter. But the shock was cushioned by revenues from North Sea oil and proceeds from the sale of public assets, allowing the government to exit the recession without fiscal expansion, on the contrary lowering taxes on income and cutting expenditure.footnote47 The magnet of deregulation attracting a major influx of overseas capital: foreign ownership of local assets quadrupled, supporting the balance of payments, while household borrowing doubled, sustaining consumption.footnote48 With these ingredients in place, a finance-and-debt fuelled boom lasted for nearly a decade, before a second and deeper recession struck in 1990–91, requiring recourse to a devaluation of sterling for recovery, without alteration of the underlying model. Investment remained stuck at the bottom of the g7 through the nineties.footnote49

New Labour inherited this model and preserved it with minimal alterations—essentially side-payments to its electorate in the form of increased social expenditures, covered by further financialization of the economy. The Blair–Brown governments saw a continuing contraction of industry; lighter regulation of banking; yet greater inflows of overseas capital—foreign ownership of equities quadrupling again; a still more distended property bubble; and higher levels of household debt. By now the balance of payments was deteriorating, along with a further deepening of the regional divide between London/South-East and the North. After 2004, a steep rise in immigration from the eu helped sustain Ukania’s low-skill/low-wage model of growth by sparing firms training costs. In the same years inequality escalated anew, to a Gini coefficient of 0.36, ‘its highest level since comparable time series began in 1961’.footnote50 Summing up New Labour’s record, a survey of 2007 observed that it had relied on a consumption binge to drive demand, whose hangover had yet to come, and ‘washed its hands of rising inequality’, with a policy-set that simply ‘refined and developed the Thatcherism that preceded it.’footnote51

Punctually, as with Thatcher, after a decade of Blair–Brown government, the economy was in deep recession again. The financial collapse of 2008, Craft confesses, came as a ‘rude shock’ to New Labour, as to admirers of its steady continuance of Thatcher’s policies. Since 2004 productivity growth had already been declining, ict gains had faded, and in 2007 the crash of Northern Rock, a year before Lehman went under in New York, set off the first bank run since the 1860s. Unlike in 1992, this time there was no political recovery for the regime in place, evicted at the polls in 2010. Looking back at the crisis, from the inner circle around Brown came the plangent query: why so? Lamenting that ‘we were neither aware of the pace and scale in change in the financial sector, nor did we comprehend its potential risks’—while not accepting any special responsibility for the outcome, since ‘almost nobody understood exactly what was going on in the markets, or the degree to which moral hazard really was affecting risk-taking. Like so many, the government largely bought into an idea of the financial sector as being the ultimate in efficient, calculating market rationality’—the answer, in its simplicity, supplied the apposite obituary on New Labour: ‘Things went wrong because everyone was fooled by the bubble and it was hard to know what else to do, especially when faced with the prospect that other countries would outgrow us if we just stood still.’footnote52 The bankruptcy of 2008 was not just economic.

Quadrupling the public debt to 150 per cent of gdp, the cost of the ensuing bail-outs left the ideological runway clear for the Conservative austerity regime that followed, whose targets were accepted by Labour. Ten years after the onset of the crisis, what is the upshot? An economy in which the stock value of real estate has multiplied 100-fold since the early 1970s, from $60 billion to over $6 trillion, attracts nearly 80 per cent of bank loans, as against a mere 5 per cent to businesses, and now accounts for a larger percentage of gdp than the entire manufacturing sector.footnote53 Between 2000 and 2017, an accumulated balance of payments deficit of £1 trillion. In the same period, a monetary base that expanded 15 times over to support asset-price values, and consumption running at over 80 per cent of gdp.footnote54 Between 1997 and 2012, an average amount of training per worker that fell by roughly a half.footnote55 Between 2007 and 2016, a labour-productivity standstill without historical precedent, at a miserable 0.09 per cent a year, costing an unexampled output shortfall estimated at close to 20 per cent of the pre-financial crisis trend. As for growth, over the same period per capita increase in gdp was just 0.19 a year.footnote56 So far as renaissance went, Britain was back at square one.

2. Ruling Bloc

From 1874 to 1997, Conservatives—holding power either alone or in coalition—dominated government, an ascendancy which no other party in Europe has ever remotely matched. For the better part of that time, some ninety years, the upper-class character of the elite that led the party remained substantially unchanged. A single index suffices to capture it. In 1950, a quarter of its members of parliament were Old Etonians, coming from a single school of 1,100 pupils, out of a population of some 50 million. Five years later, when Eden formed his government, 10 out of 18 ministers in his Cabinet came from Eton; when Macmillan took over, the number was 8 out of 18; when Home became Premier, 11 out of 24. Macmillan selected Home as his successor after consulting an inner group of just 9 colleagues—8 of them Etonians. The pick was denounced as a coup by a less favoured minister, indignant at the imposition on the party by this ‘magic circle’ of a belted earl of no particular abilities;footnote57 and when the Conservatives lost the ensuing election, choice of leadership was transferred to the parliamentary party as a whole. This would come to be seen as the real end of the ancien régime in Britain, when a hereditary governing class ceded leadership of the party to lower strata in the ruling bloc over which it had so long presided.footnote58 The turn of the petite bourgeoisie had arrived. Heath and Thatcher, the next Conservative prime ministers—offspring of a builder and a grocer—set about modernizing the country, as they saw it.

In the Commons, change was slower in the body of the party. By 1970, the 79 Etonians of 1950 had dropped to 59, and in 1979 to 51. But the numbers who had been privately educated, and who had gone to Oxbridge scarcely altered: 75 per cent and 49 per cent in 1964, 74 per cent and 48 per cent in 1974, 73 per cent and 43 per cent in 1979.footnote59 At Cabinet level, over half of Heath’s ministers were from elite schools; 4 from Eton, 2 from Harrow, 2 from Winchester, 1 apiece from Westminster and Wellington. In Thatcher’s first Cabinet, the proportion was even higher: 15 out of 21, including 6 from Eton and 3 from Winchester. But by the time of her last Cabinet, déclassement of ministers had set in: 7 out of 21. Further drops came under Major: 5 out of 25 in his first Cabinet, falling further in his chaotic second term.

In the wilderness of opposition that followed, under a triptych of duds—Hague from a comprehensive, Duncan-Smith from a secondary modern, Howard from a grammar school—the process continued. By 2005, the contingent from Eton in the Commons was down to a mere 15. By then a further rule-change had given membership of the party in the country final say in electing a new leader, from the two candidates with most support in its parliamentary delegation. This time, the result was a reversion to type: another Old Etonian at the helm, flanked by an intimate from St Paul’s, and a return to power in 2010—Cameron at Number 10, Osborne Number 11, Downing Street. When Cameron resigned in 2016, there was a brief interregnum under May—better-born than Thatcher or Major, from the Anglican middle class—before a second product of Eton was catapulted to power, flanked by a head-boy from Winchester—Johnson at Number 10, Sunak at Number 11, Downing St.

How significant is this reappearance at the head of Conservative government of leaders from the top drawer of the traditional class system? Does it signal the persistence of an underlying dna of the party for which, in altered circumstances, patrician confidence still counts for a lot in political success? Or might it be no more than a contingent blip in the transition to a more fully plebeianized formation, not just petit-bourgeois, but multi-ethnic in composition? At Cabinet level, Johnson’s ministry of 2020 is 69 per cent privately educated, where May’s of 2016 was 30 per cent, a conspicuous difference. But at Parliamentary level, the percentage of Conservative mps who were privately educated, 73 per cent in 1979 and still 60 per cent in 2005, had fallen to 41 per cent by 2019, while those coming from Oxbridge, 51 per cent in 1997, were down to 27 per cent.footnote60 In other words, socially speaking, over the past decade leaders and cadres have moved in opposite directions. Membership of the party, 130,000 under Cameron, is currently up to 191,000, but two-fifths of these are over 65, and the same proportion essentially passive.footnote61

If this is now a structure out of balance, far removed from the post-war era when the apex of the party in government and its support in parliament were cut from the same cloth, sustained by the deference of a mass membership a million strong in the country, oligarchic education can still act as a stabilizer of it in reserve. Looking back, after 1964 all of the males picked from the lower middle class for leadership of the party were failures: Heath a fiasco, Major a mediocrity who split the party, Hague, Duncan-Smith and Howard scarcely recallable. Thatcher was the sociological exception, a woman who by force of character and conviction changed the country. After the wash-outs who followed, Cameron brought the party back to life with a shot of born-to-rule confidence. Sure he could carry a referendum he had little need to call, his undoing was an excess of it. Johnson seized power with a bolder, more flamboyant demonstration of the same insouciance, the first politician in his party ever to pull off a capture of it in open revolt against its orthodoxy of the time, succeeding where Churchill’s father and then Chamberlain’s had failed. How far the will-to-rule may take him remains to be seen.

Sociologically, continuity of background in elite private schools does not mean the formation they offer their charges persists unaltered. In the conclusion to their summum British Imperialism 1688–2015, Peter Cain and Tony Hopkins write of two basic changes in the constitution of the country’s traditional rulers. Culturally, their training is no longer the same. In public schools, character-building remains central, but there is now a ‘progressive privatization of character. The new definition emphasizes such qualities as “ambition, self-confidence and bloody-mindedness”. It omits the notions of duty, self-sacrifice and public services that were taught to English gentlemen in the days of imperial glory. The new elite is being shaped by a much more individualistic creed than were its forebears because it is being prepared for entry into an increasingly cosmopolitan, supra-national world, where traditional gentlemanly values are no longer central.’footnote62 Economically, as finance and industry in the uk pass ever more widely into foreign hands—banks, utilities, airports, steel, auto, retail, football clubs, appliances—the links between capital, ever more global, and class, still politically local, have weakened. The City, no longer dominated by investment banks of native stamp, has lost the position it once held in the governing firmament. Business at large enjoys less direct purchase in the counsels of party and state than in the past.

The upshot remains ambiguous. If the possessing class can be distinguished as a formation at once ‘in’ and ‘for’ itself, the ruling bloc as such is objectively larger and richer—gorged on asset prices—than ever before, modernized in the sense of increasingly ‘diverse’ (noblesse d’écran; brown-skinned duchesses; abolition of male primogeniture in the House of Windsor; an honours system still attracting, like flies to molasses, former feminist firebrands and onetime Marxist professors). But if it’s no longer ‘for itself’ in a coherent sense, this has been the product of a step process, played out across successive generations, in which Britain has experienced neither political rupture nor military occupation, rather a series of relatively painless abdications of sovereignty, but still bolstered by tattered prestige and eventually growing wealth. In effect, slow and well-cushioned regression to drone status: 1914–18, loss of world leadership; 1947–62, loss of empire and in 1956 of international sovereignty; in the 1980s, conversion of the City into a service centre for overseas banks, dissolving recognizably national wealth into more diffuse global holdings; in the 1990s, demotion of regional status with the reunification of Germany; in the new century, of global status with the rise of China.

Yet between the wars it was Keynes, for all his talk of the euthanasia of the rentier, who continued to view the City not just as vital to jump-starting the global economy (no other centre could offer its unique blend of investment capital, commercial finance, insurance and other services) but also to securing Britain’s leadership as a great power alongside the us, with an international currency independent of it. Half a century later, the aim of the Big Bang of 1986 was not so different. In its battle with New York, Tokyo and other financial rivals, what mattered to Britain was the size and liquidity of the markets and deals done in the City, not who owned the firms betting in them. The City’s economic weight and class character may have changed a lot, but even in a subordinate capacity, is it any less a geo-political prize for the British state than before? Faute de mieux, and with few other chips to play—arm and high-tech firms in defence or pharmaceuticals are on the chopping block too—access to the City and its loosely regulated markets and services will no doubt continue to be a bargaining counter in future trade deals.