On a late summer’s evening in 1956, the bbc’s Third Programme broadcast—in two 45-minute parts, separated by a gramophone recording of Ravel’s song cycle, Histoires naturelles—a talk on ‘Performative Utterances’ by J. L. Austin, Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Oxford. The term ‘performative’ (which he admitted was ‘ugly’, even though it seems to have been he who coined it) signalled a crucial shortcoming in the positivist prejudice that ‘the sole interesting business . . . of any utterance is to be true or . . . false’. As Austin told his listeners, there are perfectly meaningful statements in ordinary language that are neither true nor false, utterances in which the speaker ‘is doing something’ rather than asserting something about a state of affairs external to the utterance—performative utterances. Imagine, for instance:

that in the course of a marriage ceremony I say, as people will, ‘I do’—( . . . take this woman to be my lawful wedded wife) . . . [W]hen I say ‘I do’ . . . I am not reporting on a marriage, I am indulging in it.footnote1

Austin’s attention to the performative has survived the eclipse of the Oxford ‘ordinary language philosophy’, of which he was a leader. Especially via Jacques Derrida—with his famous critique of the Austinian assumption of ‘the conscious presence of the intention of the speaking subject in the totality of his speech act’footnote2—and Judith Butler’s hugely influential theorization of gender, the idea of ‘performativity’ has become a pervasive reference point in the humanities and social sciences.

‘Performativity’ has, for example, been employed by the French economic sociologist Michel Callon as a way of denoting the capacity of a mathematical model or other aspect of ‘economics’ (a term he understands in a very broad sense, far broader than just the academic discipline) to be more than a representation of some external reality.footnote3 A model can do things, just as an utterance in everyday speech can (albeit in quite a different way). Performativity is, for instance, a particularly pertinent issue for mathematical models in finance. When such a model escapes from the lecture theatres and pages of academic journals into the wild—when it starts being used by financial practitioners, regulators and so on—it can affect the very phenomena it purports to describe.

Our argument is this: when analysing the effects of mathematical models on financial markets, attention ought to be paid not just to performativity, but also to ‘counterperformativity’.footnote4 Austin himself, and many of those who have drawn on his work (such as Pierre Bourdieu), have been sharply aware that, as Austin put it, more is involved in performativity than ‘the uttering of the words of the so-called performative’. (In the case of ‘I do’, for example, both partners must legally be free to marry, the ceremony must be conducted according to certain rules and by an authorized person, etc.) What Austin called ‘misfires’ or ‘infelicities’—‘the things that can be and go wrong on the occasion of [intended performative] utterances’—are commonplace.footnote5 Indeed, for Derrida and Butler, apparent failure is intrinsic to performativity’s productivity: ‘a successful performative is necessarily an “impure” performative’; ‘rupture or failure . . . characterizes every interstitial moment within iteration’; ‘breakdown [is] constitutive to the performative operation of producing naturalized effects’.footnote6

What, then, is our neologism good for? How can we, a sociologist (MacKenzie) and a literary theorist (Bamford), use counterperformativity to analyse the operations of finance and the epistemology of mathematical modelling? Abstraction and empiricism are intertwined in the very notion of counterperformativity, making it a particularly useful concept for our analysis of the curious ways in which models ‘fail’. Mathematical models are, after all, bricolage constructions inscribed with curdled utopias, with arms and with rights—so many scraps of social history.footnote7 Misfires are all-pervasive in the application of mathematics to finance: markets seldom if ever behave exactly as posited by even the most sophisticated model. ‘Counterperformativity’, however, is more than a routine misfire. It is more than just what Michel Callon—as noted above, the pioneer of the application of ‘performativity’ to economic life—calls, in translating ‘counterperformativity’ into his terminology, the failure of agencements (loosely, arrangements of human beings and non-human entities that generate specific forms of agency) ‘to discipline and frame the entities that they assemble’.footnote8 Counterperformativity is a very particular form of misfire, of unsuccessful framing, when the use of a mathematical model does not simply fail to produce a reality (e.g. market results) that is consistent with the model, but actively undermines the postulates of the model. The use of a model, in other words, can itself create phenomena at odds with the model.

This article proceeds as follows. First, to anchor the discussion, we consider the context and effects of what is arguably the twentieth century’s most influential mathematical model in finance, the Black–Scholes model of options, which was hugely important to the emergence from the 1970s onwards of giant-scale markets in financial derivatives. (A ‘derivative’ is a financial instrument whose value depends upon the price or level of another ‘underlying’ instrument, such as a block of shares. We explain ‘options’, which are a type of derivative, below.) Then we take on the article’s main task, which is to sketch the beginnings of a typology of forms of the counterperformativity of mathematical models in finance.

We identify three mechanisms of counterperformativity. The first is when the use of a model such as Black–Scholes in ‘hedging’ (trading the underlying instrument in a way designed to offset the derivative’s risk) alters the market in the underlying instrument in such a way as to undermine the model’s assumed price dynamics. Hedging might seem an undramatic use of a model, but our prime example here is the stock market crash of 19 October 1987, arguably the single specific moment of greatest danger for the us financial markets in the half century after the Second World War. The second mechanism of counterperformativity that we identify is when a model that has a regulatory function (public or private) is ‘gamed’ by financial practitioners taking self-interested actions that are informed by the model but again have the effect of undermining it. Our example here is the global banking crisis of 2007–08, beside which the 1987 crash seems minor. The third mechanism of counterperformativity is what we call ‘deliberate counterperformativity’: the use of a model with the conscious goal of creating a world radically at odds with the world postulated by the model. Actors in finance are not usually ‘model dopes’, blindly employing models, but can often anticipate what the effects of the use of a model will be. The case of this on which we focus involves a family of mathematical models advocated by the maverick French mathematician, Benoit Mandelbrot, who stood opposed both to mainstream financial economics (such as the Black–Scholes model) and to the form of ‘modernist’ reasoning hegemonic in mid-twentieth century mathematics.footnote9 As we will see, the family of models in question was adopted precisely to reduce the chances of the world they posited becoming real.

The final part of the article—our conclusion—briefly considers the place of performativity and counterperformativity in the analysis of finance. Neither concept is a panacea; both can only be supplements to other forms of enquiry, including more traditional political economy. The concepts have the virtue, however, of extending the scope of enquiry to a crucial aspect of modern economic life: its shaping by mathematical models. In particular, the notion of ‘counterperformativity’ keeps alive a necessary tension in how this should be analysed. The analyst should focus not just on cases in which models mould the world in their image, but also attend to the possibility and consequences of models doing exactly the opposite.

There is now a large literature on performativity, which we cannot review here.footnote10 However, one crucial preliminary clarification is in order. Critics of this burgeoning literature argue that using Austin’s word ‘performative’, or even simply invoking his name, misleads when one is dealing with a topic such as the effects of mathematical models on markets; one critic has even suggested that Austin needs to be saved from MacKenzie.footnote11 This latter (we hope light-hearted) formulation aside, we find ourselves entirely in agreement with a central point made by these critics. As Judith Butler notes, ‘financial theories . . . do not function as sovereign powers or as authoritative actors who make things happen by saying them’.footnote12 For traders to use a model such as Black–Scholes is not like a medieval monarch making someone an outlaw by saying that they are an outlaw: no mathematical fiat. We are dealing here not with matters of the philosophy of language, not with ‘acts [that] are constituted’ by utterances, but with causal effects.footnote13 As such, what follows is historical social science, not philosophy, and it is therefore inevitably somewhat tentative. Teasing out causal pathways in complex sequences of events is not straightforward, and the need for brevity means that the relevant evidence is at best sketched rather than laid out in full.footnote14

What can a model do?

That a mathematical model of option prices should have had any major effects at all is, in one sense, quite surprising, since the question of how options should be priced had long seemed an intriguing but essentially minor issue. Options had been traded for centuries, but typically in only an informal, semi-organized way—in the interstices or on the peripheries of mainstream financial markets, and often in quiet violation of legal bans on options trading: options were often felt to be little better than wagers. The reason for that suspicion can be seen by considering one of the main classes of option: call options. A call option gives its holder the right to buy a given quantity of an underlying asset (a block of a hundred shares, for example) at a set price on, or up to, a given future date. Optimistic speculators might, for instance, be anticipating that the shares were going to rise in value, but simply buying those shares outright would be expensive. A call option can typically be purchased for a small fraction of the price of the shares. Just as in betting on a horse race, the gain can be considerable, but if the anticipated price rise does not happen, the option’s purchaser simply loses whatever she has paid for the option.

While those who sell options (who ‘write’ them, in the terminology of the business) were and are usually professionals, purchasers of options were often laypeople. Prior to the events discussed below, the characteristics of options were not normally standardized, and—since the prices of options with different parameters are difficult to compare—the vendors of options were therefore often not under much competitive pressure.footnote15 Judged by the standards of the option-pricing theory we are about to discuss, options were typically grossly overpriced.footnote16 How options ought to be priced has, in any case, no intuitively clear answer. For many years there had been sporadic work on the problem, most famously by the French mathematician Louis Bachelier (1870–1946), now regarded as a precursor of modern mathematical finance. What has become the canonical solution was reached at the end of the 1960s by the American economists Fischer Black and Myron Scholes, and their derivation of their model was refined (and given what is essentially its current form) by their mit colleague, Robert C. Merton. The trio, especially Scholes and Merton, were firmly within the mainstream of the emergent academic specialism of financial economics, and by the time of their work the specialism’s centrepiece was already in place: the famous ‘efficient market hypothesis’, according to which prices in mature financial markets always reflect all publicly available information.footnote17

Black, Scholes and Merton modelled option pricing by assuming, quite counterfactually, that options markets already were efficient. They made a set of simplifying assumptions of the kind common in financial economics, such as that options and shares could be bought and sold without incurring fees or other transaction costs in so doing. Their underlying model of share-price movements was also standard: they assumed that those movements followed a ‘random walk’ in which price changes in successive time periods were independent of each other. In particular, they adopted the most common version of this assumption, known as the ‘lognormal random walk’, where the word ‘normal’ refers to statisticians’ famous bell-shaped curve—the ‘normal’ or ‘Gaussian’ distribution—in which the frequency of large deviations from the average (and thus, in the case of finance, the probability of extreme price movements) is very low.footnote18

On this standard foundation, Black, Scholes and Merton built an elegant and mathematically sophisticated model. Merton, in particular, had already started to pioneer the use of what has subsequently become the dominant form of mathematics in today’s derivatives markets, the stochastic calculus developed by the Japanese mathematician, Kiyosi Itô (1915–2008); it is among the ironies of today’s us-dominated financial system that crucial parts of its mathematical foundations were laid in a Japan locked into a catastrophic war with the United States. Black, Scholes and Merton showed that, given their framework of assumptions, it is possible to ‘replicate’ an option perfectly—to, in other words, construct a continuously adjusted portfolio of the underlying shares (and borrowing or lending of cash) that will have the same returns as the option in all states of the world: in other words, in any scenario within the scope of their assumptions. A trading position that consists of an option ‘hedged with’ (i.e. its risks exactly counterbalanced by) this ‘replicating portfolio’ is in their model therefore riskless, and so—following ‘efficient market’ logic—that position can earn no more, and no less, than what financial economists call ‘the riskless rate of interest’. (While that latter rate is a mathematical abstraction, a reasonable empirical approximation to it is provided by the rates of return offered by sovereign securities issued by a major government, such as that of the United States, in its own currency.)

This argument—the Merton-inflected derivation of the Black–Scholes model (whose authors had originally reached that model by more ad hoc routes)—swept aside much of the complication of many earlier models of option prices. For example, the argument relies not on the logic of speculation, on investors’ hopes for price rises or fears of price falls, but on the logic of arbitrage: the premise that two things that are worth the same (in other words, entitlements to cash flows that will be identical in all states of the world) must, in an efficient market, have exactly the same price, for if they do not savvy traders will instantly step in to exploit the discrepancy (and in competing to exploit it, will eliminate it). The combination of this conceptual simplicity and the mathematical tractability of the underlying random-walk model (Itô’s most famous result, known as ‘Itô’s lemma’, can be brought into play) makes the Black–Scholes model far simpler cognitively than it at first appears. While earlier mathematical models of option prices often had multiple parameters that could be fitted to empirical data only with difficulty, the Black–Scholes model has only one ‘free parameter’, as a mathematician would put it: the ‘volatility’ (extent of price fluctuations) of the underlying shares. Everything else is either measurable reasonably directly, such as the riskless rate of interest, or ruled irrelevant by the strong assumptions and parsimonious logic of the underlying argument.

Here, it is straightforward to see why those who are strictly faithful to Austin criticize ‘performativity’ analyses in finance. The world postulated by Black, Scholes and Merton was not brought into being by their utterance: the publication, in 1973, of their model.footnote19 Take, for example, the apparently mundane but actually crucial matter of transaction costs. Itô’s mathematics was stochastic calculus, the mathematics of processes that take place in continuous time, and in which chance events such as changes in prices happen in any time interval, no matter how short. If transaction costs are not literally zero, continuous hedging would be infinitely expensive, and thus entirely infeasible. Certainly, transaction costs have fallen considerably since 1973, but not to zero, and the effects of the Black–Scholes model are at most one factor in this fall.

Furthermore, Black, Scholes and Merton were also simply young economists, who lacked most of the normal sources of authority, even within their own profession. Black and Scholes, for example, had difficulty persuading the Journal of Political Economy to publish the paper that eventually led Scholes (and Merton) to Stockholm and the 1997 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel: understandably, given the marginality of options to the financial system at the start of the 1970s, the journal’s editor regarded their paper as of only limited interest.footnote20 Nor did traders have any automatic faith in the correctness of the Black–Scholes model. Mathew Gladstein, of the investment bank Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette, was one of the first traders (perhaps the first trader) to use their model: he had contracted with Scholes and Merton to provide him with theoretical options prices ready for the opening of the Chicago Board Options Exchange (discussed in more detail below) on 26 April 1973. ‘[T]he first day that the Exchange opened’, he recalled, the prices of the call options traded on it were 30–40 per cent higher than the model’s outputs. Gladstein’s first thought was not that the market was wrong, but that Scholes and Merton were: ‘I called Myron [Scholes] in a panic and said, “Your model is a joke.”’footnote21

That day’s events, however, marked the start of a process in which the Black–Scholes model did indeed influence financial markets, even if, as we have noted, determining precise causality is difficult or impossible. Scholes and Merton checked, and Scholes phoned Gladstein back, convincing him that ‘The model’s right’, and that there was thus a wonderful opportunity to make money selling overpriced options. ‘I ran down the hall’, said Gladstein, and ‘I said “Give me more money [for trading] and we are going to have a killing ground here.”’

The first effect of the model on which we will focus is the most clear-cut: its effect on how professional options traders talked about options. There can be dozens or even hundreds of different options contracts on a single stock: the call options explained above; put options (described in the next section); different ‘strike prices’ (the ‘strike price’ of a call, for example, is the price at which the call’s holder has the right to buy the underlying shares); different expiry dates; etc. However, because—as noted above—the Black–Scholes model has only one free parameter (the volatility of the underlying shares), it can be run ‘backwards’, so to speak, to find the level of volatility consistent with the price of an option—the ‘implied volatility’, as it came to be called. That made thinking and talking about options vastly easier: the dozens or hundreds of options on a given stock could all be compared on the single numerical dimension of implied volatility. Indeed, options traders soon came to talk about what they were doing as buying or selling volatility, not just buying or selling options.

An example is the Chicago options-trading firm, O’Connor and Associates, set up in 1977. (Although little known outside the industry, the firm was hugely influential in the evolution of the practice of modern mathematical finance.) As one of its traders said, ‘we would have a morning meeting, and [O’Connor manager Michael] Greenbaum would say, “The book isn’t long enough on volatility. We’re looking to buy some”, or “We bought too much yesterday. We’re looking to be less aggressive.”’footnote22 Indeed, eventually, implied volatility—the key parameter of the Black–Scholes model—became tradable in its own right, in the form of futures contracts and exchange-traded funds based on the Chicago Board Options Exchange’s vix, its index of implied volatility.footnote23

A second effect, harder to document, is the way in which the Black–Scholes model helped options trading (which, as noted above, was long regarded as suspiciously close to gambling) gain legitimacy by connecting it to the view, rapidly growing in influence in the 1970s and 1980s, that financial markets were efficient. When the Chicago Board Options Exchange (cboe) opened in 1973, it was the world’s first organized exchange devoted exclusively to the trading of options, and the predecessor of similar trading venues set up in Philadelphia, New York, San Francisco, London, Amsterdam and elsewhere. The cboe’s founders at the Chicago Board of Trade faced a long struggle to persuade regulators to permit their new venture: one regulator compared options to ‘marijuana and thalidomide’.footnote24 The Board of Trade commissioned the economic consultancy, Nathan Associates, to build the case for options trading, and the firm in turn commissioned prominent academic economists to help it argue in its 1969 report that ‘the more strategies are available to the investor, the better off he is likely to be’.footnote25

The work of Black and Scholes, which was still not fully completed at that point, was not drawn upon in the Nathan Associates’ report. By the mid 1970s, however, what Black, Scholes and Merton had done was seen by their fellow economists as a deeply insightful extension of the field’s ‘efficient market’ reasoning. Burton Rissman, Counsel to the cboe, believes it was their work that finally banished the association of options with gambling:

Black–Scholes was really what enabled the [Chicago Board Options] Exchange to thrive . . . it gave a lot of legitimacy to the whole notions of hedging and efficient pricing, whereas we were faced in the late 60s–early 70s with the issue of gambling. That issue fell away, and I think Black–Scholes made it fall away. It wasn’t speculation or gambling, it was efficient pricing.footnote26

A third effect of the Black–Scholes model was on patterns of pricing. What can justifiably be asserted here needs, however, to be formulated with care. Certainly, there were instances in which the most crucial early material instantiations of the model—sheets of theoretical options prices, sold as a service to traders by Fischer Black—were used directly as price quotations.footnote27 More generally, however, the model—which had never been entirely unitary (Black’s and Merton’s preferred derivations were different)—was added to and altered as it entered trading practice. Not only was it always necessary for traders to input a value for volatility before the model could generate a price, but also, for example, the specifications of most of the contracts traded on the new options exchanges differed from those in the model’s canonical solution. (If the thesis of the performativity of economics is to have any validity, it cannot be a version of the discredited ‘linear model’ of technological innovation, in which scientific ‘discoveries’ are simply ‘applied’ to practice.)

Furthermore, disentangling causality is made difficult by the fact that the publication and first uses in trading of the model coincided in time almost exactly with the opening of the cboe, at which point options changed from being simply ad hoc contracts sold by brokers (often to members of the general public), and became standardized contracts on an organized exchange on which professional traders could compete both to buy and to sell options. While the prices of options rapidly fell towards the kind of level that the model would suggest as appropriate, it is impossible to be certain how much of the fall was due to use of the model and how much to this change in market structure.footnote28

The feature of patterns of options prices that seems most likely to be related to the use of the Black–Scholes model concerns the crucial input to the model, volatility. In the logic of the model, this is a feature of the underlying shares, and therefore should not be affected by the specifics of options contracts, such as the ‘strike price’—the price at which an option gives the right to buy or to sell those underlying shares. Checking whether or not this was the case empirically was the central feature of the crucial early econometric tests of the model by the financial economist Mark Rubinstein, tests that the model broadly passed.footnote29 But there may well be a crucial element of performativity here. When an options trader subscribed to Black’s pricing service, among the initial instructions he or she received was how to identify pairs of options on the same underlying shares whose implied volatilities were different, so that he or she could ‘spread’: buy the cheaper option (the one with the lower implied volatility), and sell the dearer.footnote30 Trading in this way would of course have the effect of reducing discrepancies in implied volatility, thus—if our hypothesis here is correct—helping the Black–Scholes model pass its crucial econometric tests.

i. gamma traps

Despite the many necessary caveats, we think that it is justifiable to talk of the use of the Black–Scholes model having effects on markets, among which were processes that changed the world in ways that, to put it very crudely, made the world ‘more like’ the model.footnote31 A view of performativity, however, that focused only on these processes would be a dangerous one, and our argument in this article is that it is necessary to give at least equal weight to processes that have the opposite effect, that change the world to make it less like the model’s postulates—in other words, counterperformative processes. Again, we take Black–Scholes as our first example, although the underlying issue is by no means restricted to that model alone. As well as being directly used in trading in the ways just sketched, the model was also employed as the basis for a hedging practice called ‘portfolio insurance’. Consider what is called a ‘put option’. This is the right to sell an underlying asset at a set price. Imagine, for example, that a corporation’s shares are trading at $35. An investor in those shares could, for example, purchase a put option that gives her the right to sell them at $30. That can indeed be viewed as a form of insurance, limiting the losses that the investor will suffer if the shares plummet in price. Actually using put options in this way is expensive, considerably reducing investment returns. In 1976, however, the financial economist Hayne Leland of the University of California at Berkeley realized that rather than buying put options, investors could trade in such a way as to construct at least a passable version of the ‘replicating portfolio’ posited in the derivation of the Black–Scholes model as a perfect hedge for an option. If they did this, then they would enjoy a pattern of returns similar to those that would result from buying a put, without incurring the full expense of the latter.

It was an attractive idea, and as share prices boomed during the 1980s, increasing numbers of institutional investors turned to the advisory firm that Leland helped to set up (and to other firms offering similar ‘portfolio insurance’ services), to ‘lock in’ the gains they had made. Crucially, however, a Black–Scholes replicating portfolio is not a fixed thing, but needs to be adjusted continuously as the price of shares moves: again, recall that the underlying mathematics is Itô’s stochastic calculus. No portfolio insurer traded literally all the time—we concede, once again, to our Austinian critics that a fully fledged, literal Black–Scholes world cannot be created—but they did adjust their trading positions relatively frequently, often daily.

The hedge required to keep synthesizing a put involves selling more and more of the underlying asset as its price falls. Hedging—a procedure designed to reduce risk—can trigger a self-reinforcing adverse spiral in the price of the underlying asset, a spiral that can create asset-price changes at odds with the model that informs the hedging. That possibility is the first form of counterperformativity that we identify in this article. It is not a danger restricted to put options or to the Black–Scholes model alone. As derivatives markets grew in scale from the 1980s onwards, the methodology underpinning Black–Scholes—identify a continuously adjusted portfolio of more basic assets that will replicate the returns on the derivative, use the cost of the portfolio to price the derivative, and hedge the derivative using the portfolio—was applied to a wide variety of novel financial products. In the highly mathematical world of modern finance, even the phrase traders use to identify the danger is mathematicized. They talk of falling into a ‘gamma trap’, in which the hedging required by the model underpinning their derivatives trading forces them to buy the underlying asset on an increasing scale as its price rises, or sell it as its price falls. ‘Implied volatility’ is by no means the only mathematical parameter that has entered traders’ parlance: because Greek letters are standardly used to denote these parameters, they are collectively known as ‘the Greeks’. ‘Delta’ is the first derivative (in the mathematical sense of the term ‘derivative’) of the price of an option or similar product with respect to the price of the underlying asset, and the value of delta determines the necessary size of the hedge. ‘Gamma’ is the second derivative, the rate at which delta changes—and thus the rate at which the hedge needs to change—as the price of the underlying asset moves.

Events in financial markets that are probably the result of gamma traps seem far from unusual, even if rarely reported beyond specialist outlets such as Risk magazine: no journalist would welcome the task of having to explain ‘gamma’ to a general readership. There is, however, one cataclysmic episode that can be analysed as a gamma trap on a giant scale: the us stock market crash of October 1987.

There are uncomfortable analogies to the current epoch: a right-wing President, tax cuts, a big expansion in government debt, an economic boom, and a stock-market surge accompanied by growing fears over its durability. That there was going to be a stock-price ‘correction’ was widely anticipated. The speed with which it happened, however, was not. On 19 October 1987, the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 22.6 per cent, its worst ever one-day fall, worse than even the most terrible days of the Wall Street Crash of 1929. The more broadly based Standard & Poor’s 500 index fell 20 per cent, and the price of S&P 500 two-month index futures on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, the instrument most widely used by portfolio insurers, fell 29 per cent.footnote32 That last fall was grotesquely unlikely on the loglinear random walk model of share prices underpinning Black–Scholes: its probability was 10 to the power of –160, as reported by the financial economists Jens Jackwerth and Mark Rubinstein.footnote33 To the extent that the fall was exacerbated by a gamma trap in which portfolio insurers frantically sought to increase their hedges as prices fell, it was a counterperformative effect: a practice based upon the Black–Scholes model undermined the foundations of that model.

Once again, the difficulties of establishing historical causation intervene: it is hard to be certain, even in retrospect, just how much portfolio insurance contributed to the crash.footnote34 What cannot be gainsaid, however, is the extent to which the events of that terrible Monday sparked fears of the collapse of the us financial system. For example, Hayne Leland reports his firm’s futures trader telling his bosses that day that if he tried to make all the sales that the synthesis of a put required he would simply make prices ‘go to zero’, perhaps even forcing the closure of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange and the stock markets to which it was linked. After the day’s trading on 19 October, staff of the Mercantile Exchange’s clearinghouse stayed up all night, desperately trying to achieve the transfers of funds necessary to balance the clearinghouse’s books and allow the Exchange to open on 20 October, a process that was completed, with only three minutes to spare, by what was in effect an emergency loan from the Continental Illinois Bank, verbally agreed in a phone call with the bank’s chair.footnote35 The firms of ‘specialists’ that kept trading going on the New York Stock Exchange exhausted much of their limited capital on 19 October, and its chair John Phelan kept it formally open on 20 October—even though, in the absence of buyers, trading in most stocks had ceased—only because he had received an appeal from the White House not to close, and privately feared that any closure would be permanent.footnote36

The trauma seems to have had enduring, possibly permanent, effects on the pricing of options. The period in which the Black–Scholes model broadly passed the econometric tests described above came to an abrupt end. Patterns of implied volatility—‘skews’ or ‘smiles’—inconsistent with the Black–Scholes model replaced the flat lines that the model posited, and those flat lines have not reappeared with the passage of time.footnote37 Why that is so is a complex question that cannot be addressed here, but let us reiterate the crucial point: to the extent that the 1987 crash was exacerbated by sales, informed by the Black–Scholes model, by portfolio insurers, it was an episode of counterperformativity. The use of the model undermined central postulates of the model and did so in a way that appears permanent in its effects.footnote38

ii. gaming

Viewed in the aftermath of the 2007–08 global banking crisis, the 1987 crash seems a much less serious event than it appeared at the time. The Federal Reserve was able fairly quickly to convince market participants that it would make sufficient funds available to salvage key markets. In contrast, more than a decade on from 2007–08, the reverberations of the crisis of those years are still being felt. That many of finance’s mathematical models failed in 2007–08 is well-known. There was, in our view, a counterperformative process at work, but one that is of a different kind from the hedging-driven ‘gamma trap’ mechanism described in the previous section. Because the overall contours of the crisis will be familiar to most readers, and it is not necessary to understand the details of the models in question to grasp the basic counterperformative process, we can be more schematic in this section of our article than in its predecessors.footnote39

The mechanism of counterperformativity most central to the crisis was the ‘gaming’ of mathematical models employed for regulatory purposes, both public and private. In terms of public regulation, the crucial models were those mandated by regulators as means of determining the amounts of ‘equity’ capital—roughly speaking, equity is shareholders’ capital, although the matter is more complex than that—banks had to hold to back up their lending and the risks they took in their trading. If a bank incurs losses, those impact first on equity capital, and only if equity is exhausted should depositors, others who have lent the bank capital, and eventually tax payers have to bear losses. ‘Equity’ is thus the crucial risk-absorbing cushion. Banks’ senior managers dislike needing to have what they consider to be excessive amounts of equity, if only because a crucial metric of their success in the eyes of the stock market is their bank’s ‘return on equity’: its profits divided by its equity capital, a metric that is most easily enhanced by minimizing equity. So there was—there still is—an incentive to find ways of conducting risky but potentially profitable business that escapes, partially or completely, the mathematical models, insisted upon by regulators, that determine minimum acceptable levels of equity.

This process interacted fatally with a different, but structurally similar, process of ‘gaming’ models used for what is in effect private regulation by the credit-rating agencies. As their name implies, those agencies award ratings to borrowers (and financial instruments based upon borrowing): aaa for the most creditworthy; bbb for less solid but still ‘investment-grade’ borrowers; bb or lower for those deemed not to be investment-grade (‘junk’ in market parlance). Although the rating agencies fiercely defend the view that those ratings are simply opinions—seeking crucial First Amendment protections against lawsuits in the United States—ratings had regulatory force prior to 2008, a force diminished but not entirely eliminated by subsequent reforms. Many institutional investors, for example, were constrained by their mandates to hold primarily (or in some cases, exclusively) financial instruments rated investment-grade. Banking regulators also in effect outsourced some of their tasks to rating agencies, whose grades were an important input into the determination of necessary levels of equity.

It is a truism of finance that expected return goes hand-in-hand with risk. The safe investment that genuinely promises high returns is a will-o’-the-wisp; the riskier the borrower, the higher the rate of interest that they can be charged, and—if all goes well—the greater the value of the loan. Again, this provides the incentive for gaming, in this case of the rating agencies’ models: if a financial instrument can be packed with risky loans, but still retain high credit ratings, it will become an attractive investment that will earn its constructors high fees.

For much of the twentieth century, credit rating involved experienced human judgement being applied to relatively simple, familiar instruments such as the bonds (i.e. the tradable debt) issued by corporations. From the 1980s onwards, however, far more complex ‘structured’ financial instruments became popular and required rating: mortgage-backed securities (mbss); other asset-backed securities (abss); and collateralized debt obligations (cdos). With an mbs containing several thousand mortgages or a cdo containing the bonds or other debts of a hundred corporations, and with complexity growing fast (particularly important to the 2007–08 crisis were abs cdos, in other words cdos whose component parts were tranches of abss), it was unsurprising that the rating agencies turned increasingly to mathematical modelling. Among the models they adopted, for example, was one already heavily used by banks to model cdos: the Gaussian copula.footnote40

Although the Gaussian copula had some of its roots in the Black–Scholes model, it was not a model of the kind prized by the ‘quants’ who were energetically applying the Itô calculus in investment banking. The Gaussian copula nevertheless usefully served pragmatic purposes, and indeed became entrenched as the ‘market standard’ even when new models of the kind quants preferred became available. That a model has flaws, however, is not counterperformativity. The deeper issue, affecting not just the Gaussian copula but also the quite different models employed to rate mortgage-backed securities, was that the rating agencies made the details of the models they used public, and indeed allowed the constructors of mbss, abss and cdos simply to download those models in the form of software packages.

Transparency is of course an oft-lauded modern virtue, but in being transparent in this way the rating agencies turned the construction of an mbs, an abs or a cdo into an optimization problem. The challenge became finding the highest-yielding package of debts (or, in the case of cdos, tranches of mbss, abss, or—eventually, in the later, most baroque phases of the process—even tranches of other cdos) that would nevertheless produce an instrument that could achieve the high ratings necessary for it to be sold profitably. Often, this was a trial-and-error process, involving repeated changes to the proposed pool of debts and rerunning the software. But computerized systems were also discreetly available that automated the optimization: two interviewees whom we cannot name helped construct such systems, one within a bank, the other as a commercial product.

Hence counterperformativity. As we have already said, risk and return in finance go hand-in-hand. Finding the highest-yielding combination of debts that could achieve the desired ratings was tantamount to finding the riskiest combination. Although the ratings profiles of mbss, abss and cdos remained broadly stable through time, the quality of the debts that made them up deteriorated. That in its turn fed back into the underlying process of lending, in a way familiar to anyone who has read Lewis’s The Big Short or seen the film based on it.footnote41 (Viewers of the film may feel that it exaggerates for effect, but MacKenzie—whose interviews cover the events depicted—can testify that the flamboyant characters and reckless lending it portrays have a foundation in fact.)

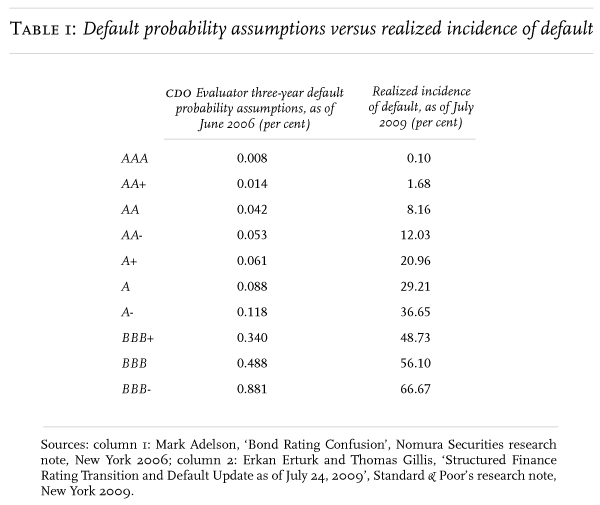

The sharpest manifestation we have found of the counterperformative process at the heart of the global banking crisis is Table 1. It compares the assumptions about the default rates of subprime mortgage-backed securities built into the 2006 version of the rating agency Standard & Poor’s model for evaluating cdos with the subsequent actual rates; the latter, as the table shows, were around a hundred times the former. (The reason this is central to the crisis is that the resultant losses, which accumulated at the core of the global financial system, manifested themselves in the insolvency of many systemically important financial institutions.) It is easy to read that table and conclude that Standard & Poor’s model was simply wrong, but the 2006 assumptions were perfectly defensible in the light of experience before the bursting of the price bubble in the us housing market. Rather, our argument—our claim of counterperformativity—is that those assumptions made possible, via their gaming by market participants, the construction of securities that radically undermined them.

iii. deliberate counterperformativity

In a stimulating contribution to the literature on performativity in economic life, Elena Esposito points to the pervasiveness of what, drawing upon the social theory of Niklas Luhmann, she calls ‘second-order observation’.footnote42 Translated into our terms, it is not simply that mathematical models in finance have performative and counterperformative effects, but actors observe or anticipate those effects and act accordingly. A recurring suspicion that actors within finance have about the many models that involve the bell-shaped normal distribution, on which extreme events are very unlikely, is that their use can have the counterperformative effect of increasing the likelihood of those events.

In the 1960s, when modern mathematical finance was gaining momentum, a very different family of models was being advocated by the mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot. From his days as a student in Paris in the 1940s, Mandelbrot had self-consciously stood apart from the ambitious project, dominant in France and also influential elsewhere, rigorously to reconstruct the entirety of mathematics on the basis of a formalized theory of sets. The project—which even touched high-school mathematics in the form of the ‘new maths’ of the 1960s—was the work of a group of French mathematicians who adopted the collective pseudonym Nicolas Bourbaki. Mandelbrot claims he spent only one day as a student of the École Normale Supérieure in 1945: resigning after the first day because he saw that the ‘Bourbaki cult’ was taking over the school.footnote43 He wrote in his memoirs that his uncle, the Bourbaki member Szolem Mandelbrojt, was ‘upset and afraid’ by his nephew’s decision to change schools: ‘the way any fanatic, scientific purist fears new alloys’.footnote44

‘I’m always ready to look at anything curious and bizarre’, Mandelbrot remarked.footnote45 He was fond of an autobiographical synecdoche: when interviewed, he said that an important thread running through his work began with a book review he found in his uncle Szolem’s wastepaper basket.footnote46 The review was of George K. Zipf’s Human Behaviour and the Principle of Least Effort, which reported the multi-language word-frequency distribution known as ‘Zipf’s law’, and sparked Mandelbrot’s persistent interest in what statisticians call ‘fat-tailed’ distributions: those in which the frequency of extreme events is far higher than in the well-behaved normal distribution.footnote47 What Mandelbrot was advocating in the 1960s was a family of distributions identified by one of his teachers at the École Polytechnique, Paul Lévy. Lévy’s distributions are characterized by a parameter called alpha, which is always greater than 0 and no greater than 2. The lower the value of alpha, the more fat-tailed the distribution. An alpha of 2 corresponds to the normal distribution, but if alpha is less than 2 the tails of the distribution are sufficiently fat that the statistician’s standard ways of measuring a distribution’s spread (the ‘standard deviation’ or its square, the variance) are infinite: the integral-calculus expression that defines them does not converge, so they have no finite value. Mandelbrot was briefly a major influence on the University of Chicago economists developing the efficient-market view of finance, especially on the formulator of the most explicit form of the efficient-market hypothesis, Eugene Fama.footnote48 An infinite variance, however, renders standard econometric procedures inapplicable, and, after mainstream financial economics’s short-lived flirtation with Lévy distributions, it turned its back on them. It was therefore a considerable surprise to MacKenzie when in fieldwork in Chicago in 1999–2000 he found those distributions being used by the Options Clearing Corporation (occ).

The occ occupies an utterly central position in options trading in the us: it is the clearinghouse for all exchange-traded options. When one trader or one algorithm sells an option, and another trader or algorithm buys that option, they do not enter into a contract with each other: each of them enters into a contract with the occ. If the occ were to fail—like the clearinghouse of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, occ was also in peril in the aftermath of the 1987 crash, with staff spending three successive nights awake in their offices, and with the Federal Reserve having to intervene to avert the bankruptcy of the occ’s leading member firm, First Options—then organized options trading in the United States would collapse.footnote49

Clearinghouses such as the occ protect themselves from calamity by requiring what’s called ‘margin’. Options traders have to have money on deposit at clearing firms such as First Options, and these firms in their turn have to deposit ‘margin’ with occ. In the event of adverse price movements, clearing firms and occ issue a ‘margin call’: a demand for an additional deposit. The level of margin is not set arbitrarily, but on the basis of a mathematical risk model.

The occ had come to realize that a risk model based upon the assumption of normal distributions could be counterperformative. Because, so to speak, a normal distribution does not ‘expect’ an extreme price movement, if one occurs, the statistical estimator of the key parameter, the variance of the distribution, can suddenly soar. If that parameter determines the requirement for ‘margin’, the result will be a very large margin call, which in the words of an interviewee then at the occ can have ‘a secondary feedback effect that adds to the volatility’.footnote50 Hence the rationale of switching to a Lévy distribution with an alpha below 2 (painstaking econometric work by the occ—as noted, an infinite variance makes econometrics difficult—pointed to an alpha of around 1.65 being appropriate). Because a Lévy distribution of this kind ‘expects’ extreme events, when such an event happens, the estimators of its parameters do not change much, and margin requirements based on those estimators do not suddenly rise, so eliminating the feared ‘secondary feedback effect’. The choice of a Lévy distribution was thus informed by the hope of counterperformativity: the goal of assuming a world in which catastrophe was a likely event was precisely to reduce the chances of catastrophe. Unlike our previous examples, in which counterperformativity was an unwanted effect, here it was actively desired.

Futures

We have no illusion that our three-fold categorization of counterperformativity is complete: we expect that others can add to it, and hope that they will do. Nor do we for a moment intend that investigation of the performativity or counterperformativity of mathematical models should displace other forms of analysis of finance. For instance, the rise of options and other forms of derivatives cannot be understood in isolation from broader processes such as the collapse of the Bretton Woods agreement and the rise of free-market economics and of deregulatory impulses. To take an example of a quite different kind, Chicago’s open-outcry trading pits were places of the body as well as of the use of Black’s sheets—and specifically places of male bodies, places often uncomfortable for women. The patterns of interpersonal relations among options traders left their traces on price movements,footnote51 and, more generally, the structures of financial markets—including the advantages enjoyed by incumbents—remain important, even in today’s world of algorithmic trading. The causes of the global financial crisis go far beyond the counterperformative process on which we have focused, and centrally include phenomena of the sort focused on by political economy of a more traditional kind, including Marxist political economy. As such, all we would claim is that ‘performativity’ is a useful addition to the conceptual toolkit necessary for understanding economic life. Mathematical models are by no means the only phenomena that have a performative aspect, but they are ever more important. An algorithmic economy is an economy of logical operations and mathematical procedures, and therefore a mathematical economy.

Why ‘counterperformativity’, and not simply ‘performativity’? We have some sympathy with another set of critics of the application of the latter to economic life, of which Philip Mirowski is the most prominent.footnote52 An analysis that neglected Derrida’s and Butler’s warnings, and focused only on cases of ‘successful’ performativity, might promote a renewed form of complacency, in which mathematical models—or, for example, other forms of orthodox economics—are indeed seen as ‘working’ (albeit not because they begin as correct representations of the world, but because they have the power to change it). ‘Counterperformativity’, in contrast, highlights a necessary tension. A mathematical model can indeed be a powerful thing, but how it changes the world is inherently unpredictable.