In the Turkish general election of June 2015, the left-wing Peoples’ Democratic Party (hdp) won 13 per cent of the vote and eighty seats in the country’s parliament—a spectacular result for a political organization that had been formed less than three years earlier, and the first time in Turkey’s history that a radical-left party had achieved such success. Since that promising debut, the hdp has faced a whirlwind of repression orchestrated by the ruling Justice and Development Party (akp) and its leader Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Thousands of hdp members have been arrested, including its most prominent leaders; large-scale mob attacks have vandalized party offices in many parts of western Turkey; terrorist bombings have ravaged its public rallies. The anti-hdp fervour has been fuelled by an upsurge in ethnic Turkish chauvinism as violent clashes between state security forces and Kurdistan Workers’ Party (pkk) guerrillas in the country’s south-east intensified. The ability of the party to maintain its political foothold in the face of this pressure remains open to question, but it has already left a significant mark on Turkish society. The hdp’s trajectory can only be understood against the longer historical backdrop of struggles for the construction of a genuine democracy in Turkey, and for a significant left-wing force within that democratic space.

If the hdp’s gains in the 2015 election were unique in the annals of Turkish politics, the history of radical activism in the country reaches back much further. Exiles based on Soviet territory founded the Communist Party of Turkey (tkp) in 1920, but its leader Mustafa Suphi was lured into a trap by the Kemalist regime the following year and assassinated along with a number of his comrades. The tkp was a marginal force, despite the adherence of leading public intellectuals such as the country’s greatest poet, Nâzım Hikmet, and remained illegal until 1946, when Atatürk’s successor İsmet İnönü liberalized the Turkish political system from above.footnote1 The left-wing movement only began to develop into a popular force during the 1960s, when the Workers’ Party of Turkey (tİp) was set up by a group of trade unionists. The new party argued for a parliamentary route to socialism and contested the 1965 general election, winning just under 3 per cent of the national vote and drawing support from the Kurdish-majority areas, which supplied three of its fifteen mps.footnote2 For a time, the tİp managed to raise the demands of workers and peasants within the Turkish political system, but its poor performance in the 1969 election resulted in a bitter factional struggle.footnote3 Soon after the military coup of March 1971, the party was closed down and its leaders imprisoned. In the years that followed, repression of the main opposition forces—especially left-wing and Kurdish activists—intensified, with thousands detained and tortured.

New left groups proliferated during the 1970s, but the movement was highly fragmented, drawing on every competing strand of Marxist ideology, and had to operate in a violent political environment. Influenced by Maoist or Guevarist precepts, many Turkish socialists raised the call for guerrilla warfare against the state, but their capacities in this field were always greatly inferior to those of a burgeoning far-right movement, whose ‘Grey Wolves’ could count on friendly support from within the state machine. Turkish nationalism also exercised a strong influence within the socialist movement, making it harder to develop a programme that could appeal to the country’s minorities, especially the Kurds. Political violence between left and right increased during the second half of the 1970s, and the socialist groups remained bitterly divided. On 12 September 1980, the Turkish military seized power, delivering a hammer blow against the left. The junta imprisoned thousands of activists, and hundreds were executed or died under torture; many others fled the country for exile in Europe.

When Turkey’s generals returned the country to civilian rule in 1983, its socialist movement had been crippled. A new constitution imposed a 10 per cent threshold for parliament that was meant to exclude dissenters from the political system. Under these conditions, the Turkish left could barely make an imprint on the post-dictatorship landscape. During the late 80s and early 90s, the main vehicle for progressive voters was the centre-left Social Democratic Populist Party (shp), which won nearly 25 per cent of the vote in 1987 and 20 per cent four years later. But the shp was unable to develop a viable left-wing programme that could challenge the grip of Turkey’s dominant conservative parties. After 1991, it was absorbed into a coalition government headed by Süleyman Demirel’s centre-right True Path Party, and by the mid 90s had merged with the Kemalist Republican People’s Party (chp). A number of smaller groups were also active during the 1990s and 2000s, but their efforts did not result in any notable success.

Overall, the record of the Turkish left must be considered one of failure. Even before the 10 per cent threshold was introduced, its parties struggled to make any real impact on the electoral stage. Its capacity for extra-parliamentary mobilization was greater, especially in the 1970s, but a divided movement was unable to resist the coup and never fully recovered from the blows inflicted by military repression. When Erdoğan’s akp began to rise as a political force in the new century, many erstwhile left intellectuals rallied to its banner, hoping that the Islamists could succeed where they had failed in liberalizing the political system and cutting the army down to size. This abdication offered striking evidence of a historic eclipse.

Kurdish awakening

However, the Kurdish national movement would pose a much more formidable challenge to Turkey’s ruling establishment, compensating for the weakness of the country’s left. Turkey has the largest Kurdish community in the Middle East, some fifteen million people (about a fifth of the overall population); fifteen provinces in the south-east are at least two-thirds Kurdish. Often enlisted by Turkey’s rulers for violent struggle against the Armenians—including the genocide of wwi—the Kurds then found themselves denied any official recognition under the Kemalist regime, which dubbed them ‘mountain Turks’ and repressed their language and cultural identity. The majority lived in rural districts, where more than half of the arable land was owned by less than a tenth of the wealthiest families. Two-fifths of the Kurdish population were landless peasants who survived as sharecroppers, or by working for the tribal chief; the remainder had small plots of four to five hectares. Tribes had become the dominant form of social organization among Kurds after the abolition of the Kurdish emirates by the Ottomans in the nineteenth century; subsequent political and economic developments altered this function, but did not efface it. The endemic poverty and backwardness of the south-eastern regions combined with the weight of national oppression to generate a vast reservoir of discontent.

The 1970s saw a growing radicalization of the Kurds, with the founding of several clandestine parties based on socialist ideology. The relentless persecution of all forms of Kurdish political expression persuaded many activists that it was time to take up arms against the state. The pkk was set up in 1978, with Abdullah Öcalan as its leader. Born in the rural south-east, Öcalan was strongly influenced by the Turkish Marxist left during his time as a student at Ankara University in the early 1970s but, like many Kurds, believed that the existing groups did not show enough respect for Kurdish identity. What set the pkk apart from the other Kurdish organizations was its ability to survive the repression unleashed by the 1980 coup. The party had shifted many of its cadres to Syria and to Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley before the military seized power, and began preparations for a full-scale insurgency. In August 1984, its armed units carried out the first attacks on military posts near the border with Iraq.

Öcalan’s movement went on to fight a guerrilla war that lasted until 1999, long after the urban guerrillas of the 70s Turkish left had been contained and defeated by the state. Öcalan was accused by critics of stifling dissent and imposing himself as the pkk’s unquestioned leader, but enjoyed great respect within the movement and in Kurdish society as a whole. The pkk developed into a popular national-liberation movement, with a guerrilla force of 15,000 fighters at the height of its power in the early 1990s. The movement had several million supporters and sympathizers drawn from all parts of Kurdistan, and from the diaspora communities in Western Europe—Britain, France and Germany in particular—which became an important source of finance.footnote4 This phase of rebellion was the most radical and enduring in the history of Turkey’s Kurdish community. Facing nato’s second-largest land army, the pkk held its own for more than a decade in the face of seemingly overwhelming odds. The mountainous terrain was ideal for guerrilla warfare, and pkk units were able to retreat across the border to Syria or northern Iraq when under pressure.

The state responded with fierce repression, destroying villages, organizing paramilitary ‘Village Guards’ to hunt for alleged pkk sympathizers, and clamping down on all criticism of its counter-insurgency. Ankara did its best to exploit class divisions in the Kurdish population, appealing to tribal landowners whose position was threatened by the pkk’s anti-feudal rhetoric. The violence of the state triggered mass flight from the countryside to the cities of western Turkey, which now contain almost as many Kurds as the south-eastern regions. Over 40,000 people were killed in the conflict, including pkk militants, Turkish soldiers, pro-state paramilitaries and (above all) Kurdish civilians. After abortive peace negotiations in the early 90s, the Turkish army began to get the better of its adversary, helped by huge quantities of us military aid. But the real breakthrough for Ankara came with the capture of Öcalan in 1999. The pkk chief had been residing in Damascus, but was expelled by the Syrian regime after Turkey applied heavy pressure on Assad. Öcalan sought refuge in several European countries before travelling to Kenya, where he was captured by Turkish commandos with the assistance of the cia.footnote5 To Ankara’s delight, the decapitation of the movement seemed to have finished off its insurgency. At Öcalan’s direction, the pkk called a unilateral ceasefire soon afterwards, and its guerrillas withdrew across the border to the mountains of northern Iraq. A Turkish military court sentenced the pkk leader to death—later commuted to life imprisonment after capital punishment was abolished in 2002. Öcalan was held in a special, heavily guarded prison on the island of İmralı, where for a decade he was the sole inmate.

But this was not the end of the ‘Kurdish problem’ for Turkey’s rulers, as the armed insurgency had helped catalyse a broader political awakening. This pro-Kurdish democratic movement was far more successful on the electoral stage than the Turkish socialist parties, despite facing intense state repression, and carved out a space as the main political actor articulating the demands of the Kurdish population. The first expression of the movement was the People’s Labour Party (hep), set up in 1990 by mps who had been expelled from the shp for attending a conference on the Kurdish question in Paris.footnote6 The new party had two overlapping objectives: democratization of state and society in Turkey, and a peaceful, inclusive solution to the Kurdish conflict. It sought to win support from beyond the Kurdish community, claiming to be a party that represented the whole of Turkish society.footnote7 While electoral backing for the hep and its successor groups would come overwhelmingly from Kurds, many long-standing Turkish socialist militants joined the party: by aligning with the pro-Kurdish movement, they had access to a popular base well in excess of anything the Turkish left could manage through its own efforts. Their presence helped rebut charges that the hep and its successors were purely Kurdish organizations, although this would not be enough to shield the parties from a succession of legal clampdowns.

In the 1991 election, hep candidates stood for parliament on the shp’s list and won 22 seats—an unprecedented number of pro-Kurdish mps. By the following year, however, the state security court had moved to strip the party’s representatives of their parliamentary immunity; in July 1993, it was banned altogether. The Democracy Party (dep) was then launched to carry on with a similar programme. The Turkish security establishment depicted both parties as front organizations of the pkk, which meant that the pro-Kurdish movement could be repressed without much opposition. Party activists were frequently arrested and tortured; between 1991 and 1994, more than 50 were murdered.footnote8 The dep was in turn banned outright in June 1994: four of its mps received lengthy prison sentences, and six more left the country to escape the same fate. The movement was gradually rebuilt over the following decade after this bout of repression. The People’s Democracy Party (hadep), set up in 1994, and its sister organization, the Democratic People’s Party (dehap), established three years later, were unable to win any seats in parliament due to the 10 per cent threshold, but both parties performed well in local elections, and managed to build up an organization covering many of Turkey’s cities. The hadep won almost 5 per cent of the vote in the 1999 parliamentary poll, and took 37 towns and cities in the south-east, including the municipal councils of Ağrı, Batman, Diyarbakır, Hakkâri, Siirt and Van. Five years later, the dehap won control of 54 councils.

One of the key difficulties for this movement was the dominant perception in Turkey that it was simply a vehicle for the Kurds and the political expression of the pkk. It found itself in an uneasy position, having to balance the articulation of Kurdish political demands with the constraints of operating within the established constitutional framework, which made the expression of such demands unacceptable and indeed criminal. Its role as the focal point for Kurdish activism buttressed the view that the movement was primarily for the Kurds; Turkish socialist members who were not happy with this orientation drifted away. A number of incidents—such as the pulling down of a Turkish flag during the hadep congress in 1996, and the organization of a hunger strike to protest against Abdullah Öcalan’s arrest—caused a furore in Turkey and hardened suspicion of the pro-Kurdish democratic movement.

Erdoğan’s rise

In 2002, the akp swept to power in Ankara, with a modest plurality of votes—34 per cent—but a crushing majority of seats, thanks to the distorting effect of Turkey’s electoral system. This first bridgehead would be expanded upon by Erdoğan’s Islamists to establish a position of unchallenged dominance over the next decade. The new party benefited from the exhaustion of the country’s old political class, and posed a direct challenge to the Kemalist ideology which had held sway since the 1920s. It forged an electoral coalition of rare breadth and depth, from conservative peasants and the informal proletariat of Turkey’s main cities to the liberal intelligentsia—all with the blessing of nato and the European Union.footnote9akp leaders now wanted to build up a vote bank in the south-east, which presented both a challenge and an opportunity for the pro-Kurdish parties.footnote10

On the one hand, the Islamists sought to undercut support for the Kurdish national movement by driving a wedge through its popular base. The akp’s ideology appealed to religious and socially conservative Kurds; some even stigmatized the secular, left-wing and feminist ideology of the national movement as a form of ‘Kurdish-Kemalism’. Since the 1950s, Turkey’s political parties had often selected influential Kurdish tribal leaders as their candidates; sheikhs and other religious figures were also integrated into centre-right circles and became important political actors among the Kurds. This tactic was taken up assiduously by the akp in the course of its rise to hegemony. Tribal loyalties had been weakened by the experience of the pkk insurgency and the radicalization of the Kurdish population, and traditional leaders now looked to the state for assistance in maintaining their social position through clientelism. Islamist actors such as the Sufi religious orders, the Turkish Hizbullah and the Gülen movement organized themselves through a network of civil-society groups, and charitable activities—often directed through the regional governor’s office—played an important role in building up the akp’s base at a local level. The akp also cultivated strong ties with Kurdish businessmen through the use of economic incentives, and a number of Kurds were appointed to senior positions in government—including Mehmet Mehdi Eker, agriculture minister between 2005 and 2015, and Mehmet Şimşek, finance minister from 2009 to 2015.

While these opportunistic strategies threatened to undermine support for the pro-Kurdish parties, the akp’s desire to win Kurdish votes (and smooth Turkey’s path towards eu membership) also led it to adopt a mildly reformist policy that increased the space for legal political activity and loosened some of the controls on Kurdish-language broadcasting and education. A reform of the Associations Law made it easier to set up ngos, facilitating the spread of democratic values and providing more opportunities for Kurds to represent their own interests. The evolution of the conflict between the Turkish state and the pkk also nurtured a certain political opening. Although the ceasefire ended in 2004, subsequent violence never returned to the levels of the early 90s. When the dehap faced yet another legal case to shut down its activity, a new organization, the Democratic Society Party (dtp), was created in 2005. In the 2007 election, which saw the akp increase its support to almost 47 per cent, the dtp also elected 21 mps who had stood as independents to sidestep the 10 per cent threshold. Two years later, the dtp consolidated its position as the dominant party for the Kurdish regions in municipal elections.

The extent of liberalization for the Kurds during the first phase of akp rule should not be exaggerated. One government initiative allowed a Kurdish-language tv network to be set up with state funding, but the network was forbidden to describe itself as ‘Kurdish’, and terms associated with the separatist movement (‘revolution’, ‘rebellion’ etc.) were also banned. The akp leadership was never willing to consider granting the sort of cultural rights and autonomy enjoyed by such national minorities as the Catalans or the Welsh. akp-sympathizing liberals such as Ahmet Altan, who served as the editor of Taraf newspaper between 2007 and 2012, frequently wrote columns attacking the pro-Kurdish parties for not condemning the pkk. From this perspective, widely disseminated in the Turkish media, advocacy of a political solution to the conflict amounted to support for violence. Legal harassment carried on as before: the dtp was closed down by the constitutional court at the end of 2009.

The Peace and Democracy Party (bdp) then took up the banner of Kurdish representation, negotiating an alliance with seventeen other parties and ngos for the 2011 election. The slate of independent candidates included figures like the film director and columnist Sırrı Süreyya Önder for Istanbul and the left-wing journalist Ertuğrul Kürkçü for Mersin; 35 mps were elected to parliament as independents. But this achievement coincided with Erdoğan’s greatest triumph to date: a third consecutive victory for the akp, this time with almost 50 per cent of the popular vote. It was also the high point for the akp’s electoral overture to the Kurdish population. Emboldened by its success, the akp took an increasingly authoritarian turn after 2011, working with Fethullah Gülen’s religious movement to purge the army and judiciary of its Kemalist rivals, and lashing out at critics and dissenters in all directions. Opposition to the akp’s social conservatism and free-market economic policies erupted in the Gezi uprising of 2013. The protests in Istanbul were contained through harsh repression, but Erdoğan’s party had lost its image as a force for democratic reform, and would henceforth rely on strong-arm tactics and Turkish nationalism to maintain its grip on power.

Birth of the hdp

As opposition mounted to akp rule, the pro-Kurdish movement launched a new political initiative to broaden its base: the Peoples’ Democratic Congress (hdk), set up at the end of 2011 as a representative body for groups standing in opposition to the dominant bloc in Turkey. The original suggestion for the hdk had come from the imprisoned Abdullah Öcalan, which meant that the umbrella group could count on support from the pkk and its followers. Öcalan’s political outlook had changed significantly during his years in prison. Previously reliant on textbooks of Soviet Marxism that had been translated into Turkish for his ideological formation, the pkk chief read widely in contemporary radical thought, from Foucault to Wallerstein, and was particularly taken by the writings of Murray Bookchin, whose idiosyncratic variety of anarchism became a reference-point for the new vision of ‘democratic autonomy’ for the Kurdish people articulated by Öcalan.footnote11

Other groups that helped establish the hdk included the Labour Party, the Socialist Party of the Oppressed, the Green Left Party, and various organizations that represented women, the lgbt community and the Alevi and Armenian minorities. Its stated goal was to unite individual struggles for democracy and equality as part of a wider counter-hegemonic force. In 2012, the hdk launched the Peoples’ Democratic Party as its national political vehicle; in the Kurdish-majority provinces, the Democratic Regions Party (dbp) carried the electoral banner of the congress. In terms of membership and senior personnel, the hdp proved to be more diverse than its predecessors, attracting (in addition to the groups mentioned above) figures from the Turkish left-wing and feminist movements. In the main cities of western Turkey, such as Istanbul and Izmir, the hdp won support among university students and the intelligentsia from more affluent districts. The party established a wide organizational network that covered all Turkish provinces; however, in spite of this, the membership remained predominantly Kurdish.footnote12

The hdp’s key objective was to represent the demands of those historically marginalized sectors that had been ignored by the mainstream political parties. The party programme described it as ‘a party for Turkey’s working classes, labourers, peasants, tradespeople, pensioners, women, youth, intellectuals, artists, lgbt people, the disabled, the oppressed and the exploited of all nations, languages, cultures and faiths’.footnote13 The main thrust of its economic platform was reformist, rather than proposing a socialist economic system as the Turkish left did in the past. The hdp pledged to increase the minimum wage, ban subcontracting, and ensure that health and safety standards were respected at work (a chronic problem for Turkish workers in recent years). A comprehensive welfare system would be established; the privatization of state-owned industries and services halted; the right to strike and engage in collective bargaining guaranteed. The hdp placed the rights of women at the heart of its campaigning platform; gender equality had long been a key principle for the pro-Kurdish left forces, and the new party recruited a number of well-known feminist activists into its ranks. While the hdp sought to bring about political change through electoral politics, it also called for ‘the removal of barriers preventing citizens from debating, organizing and directly participating in the decision-making process’.footnote14 The party raised the demand for a new constitution that would recognize Turkey’s ethnic, linguistic and religious diversity, with provisions to resolve the Kurdish question and guarantee the rights of all minority groups, and drew on the vision of ‘democratic autonomy’ put forward by Abdullah Öcalan, promising to devolve power to autonomous, self-governing local administrations.footnote15 The hdp also made a specific appeal to Turkey’s Alevi population, demanding that compulsory religious education be removed from the national curriculum and that Cemevis—Alevi assembly houses—be recognized as places of worship.footnote16

The presidential election of 2014 gave the hdp its first major opportunity, and the party’s co-leader Selahattin Demirtaş went forward as its standard-bearer. Born in Palu, Elazığ in 1973 to a working-class Zaza-Kurdish family, Demirtaş spent most of his childhood in Diyarbakır and studied law at Ankara University.footnote17 Before entering parliament, he was heavily involved in the Diyarbakır branch of the Human Rights Association, an important campaigning group. Demirtaş was first elected to parliament as an independent candidate in 2007, then rose rapidly to become co-chair of the bdp three years later. He established himself as the new party’s public face during its campaign, proving to be a strong media performer whose calm and confident approach won much praise. Erdoğan was the predictable winner, supported by more than half of voters and seeing off his main challenger Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu, who had been endorsed by the Kemalist chp and the far-right mhp. But Demirtaş won a little under 10 per cent of the vote and topped the poll in eleven south-eastern provinces. This breakthrough set the hdp up for the following year’s parliamentary election.

Breakthrough

In the run-up to the 2015 poll, the hdp drew on the experience and resources of the pro-Kurdish movement as well as the other left-wing and Alevi organizations. In western Turkey, the hdp selected Alevi community leaders such as Turgut Öker, Ali Kenanoğlu and Müslüm Doğan in Izmir. Well-known socialist activists like Ertuğrul Kürkçü and Sırrı Süreyya Önder stood as candidates for İzmir and Ankara respectively. The feminist activist Filiz Kerestecioğlu, Armenian rights campaigner Garo Paylan and Islamic feminist writer Hüda Kaya joined the hdp list in Istanbul. In the Kurdish-majority areas, the party chose figures that would appeal to religious and tribal Kurds, such as Altan Tan in Diyarbakır and Mehmet Mir Dengir Fırat in Mersin, who had previously been active in Islamist-leaning parties. The hdp also selected candidates that could reach out to specific minorities, such as the Arabs in Şanlıurfa and Mardin provinces.

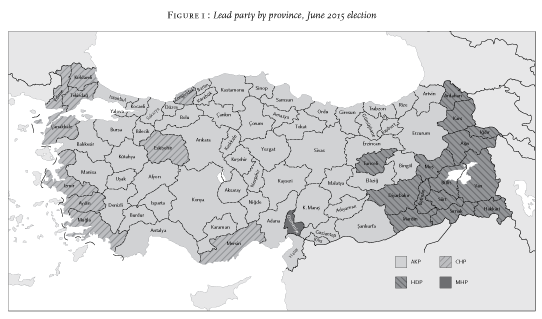

The hdp’s support rose throughout Turkey to reach an unprecedented 13 per cent, but the increase was highest in the traditional south-eastern heartlands, and in the big cities of western Turkey with substantial Kurdish populations. Slightly more than half of the party’s six million votes came from the Kurdish-majority provinces. The pro-Kurdish parties had performed well in these regions for more than a decade, but the hdp considerably increased its vote share, coming first in Diyarbakır, Van, Mardin, Batman, Şırnak, Ağrı, Muş, Ardahan, Hakkâri, Siirt, Bitlis, Kars, Iğdır and Tunceli (Figure 1, overleaf). It was the second-placed party in three other south-eastern provinces, Şanlıurfa, Adıyaman and Bingöl: regions where tribal and religious loyalties remain strong, enabling the akp to come out ahead of its rival. There was a surge in support for the hdp in Istanbul, a city that is one-fifth Kurdish, where it gained over a million votes and became the third-largest party. In previous elections, the pro-Kurdish independents had only stood in constituencies where they had a realistic chance of winning, but this time the hdp ran candidates all over Turkey; it also organized a successful overseas campaign in European countries, coming first among British-based voters. Overall, the election was a major setback for the akp, which lost 9 per cent of its 2011 vote and no longer had an absolute majority in parliament. With the chp also losing ground, only the hdp and the ultra-nationalist mhp had reason to be satisfied with their performances.

The Istanbul-based research company konda supplied a more detailed analysis of the June result.footnote18 It found that Kurds were by far the most important component of the hdp’s base, and may have supplied as many as 87 per cent of its voters. Despite all its efforts, the party had a very limited appeal to ethnic Turks: just 9 per cent of supporters were defined as Turkish, 1 per cent were Arab, and another 3 per cent unclassified. In religious terms, about 87 per cent of hdp voters were Sunni Muslims; 7 per cent were Alevi, with the remaining 6 per cent categorized as ‘other Muslim’ or ‘other religion’. The older generation of Alevi voters mostly remained loyal to the chp, the traditional recipient of their support, although the hdp made greater inroads among younger Alevis.footnote19 One-third of hdp votes came from the 18–28 age group, and more than half of first-time voters backed the party. The Kurdish portion of this age cohort is higher than average, and many younger Turks are less prejudiced against Kurds, having come of age at a time when violent clashes between the pkk and the state were at a relatively low level. The more youthful profile of the hdp leadership may also have contributed to this strong performance among new voters. The party’s electorate was poorer than the national average in Turkey. The increase in support for the hdp in the south-east and the cities of western Turkey largely came from Kurds who had previously voted for the akp: nearly one in ten hdp voters had supported the akp in the previous election, and almost three-quarters of those who switched to the hdp were Kurds. The rise was especially notable in areas that had received a large number of forcibly displaced Kurdish migrants during the 1990s, such as Istanbul, Izmir, Mersin, Adana and Gaziantep. In Istanbul, the party performed strongly in the working-class districts of Bağcılar, Esenler and Sultangazi, which contain large Kurdish populations, but also received a comparable vote in some affluent districts such as Beşiktaş, Kadiköy and Beyoğlu, suggesting that a significant number of Turks had voted for the hdp in those areas.

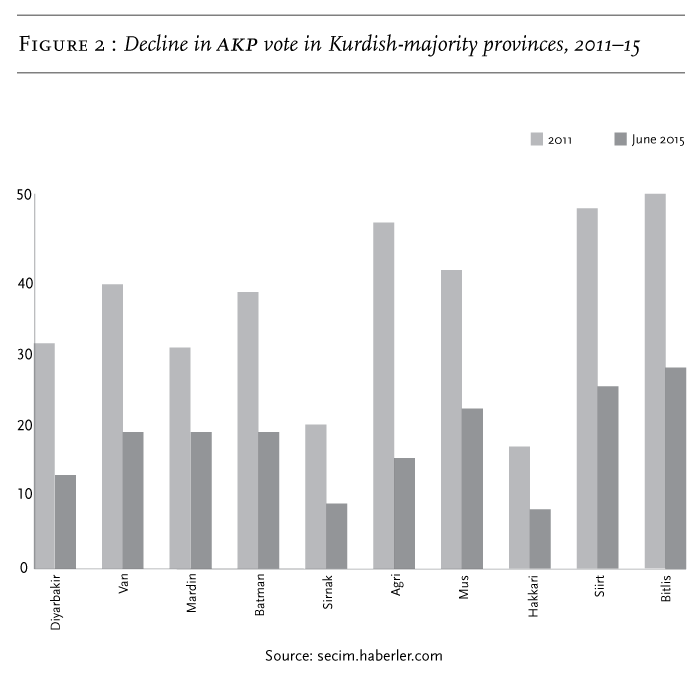

A number of factors lay behind the akp’s loss of Kurdish support (Figure 2, below). The party’s image as a force for liberalization had been tarnished by its post-Gezi authoritarian turn, but Erdoğan’s foreign-policy choices also greatly damaged the akp’s standing among Kurds. When protests in Syria developed into full-blown civil war from 2011 onwards, the Turkish leader demanded the ousting of Assad from power, expecting to have much greater influence on the regional stage when a new administration took over in Damascus. The Syrian regime proved unexpectedly resilient; to make things worse for Ankara, the pkk’s sister organization in Syria, the Democratic Union Party (pyd), took advantage of the opportunity to set up a self-governing Kurdish region near the Turkish border, known as Rojava, and equipped with its own military force, the ypg (People’s Defence Forces). The pyd tried to implement Öcalan’s blueprint for democratic autonomy under extremely adverse conditions, and found itself on the front lines of the war against isis. Matters came to a head during the siege of Kobani, just miles from the Turkish border, in autumn 2014. Erdoğan and other akp spokesmen presented the battle as a clash between two terrorist organizations, and refused to allow aid to be sent to the Kurdish fighters in Kobani. This provoked widespread protests in Turkey itself that were violently repressed by security forces, resulting in the deaths of 46 people. In the end, Turkey’s us ally decided to support the ypg with air strikes, believing it to be the only local force capable of taking on isis. This infuriated the akp, which insisted that there was no distinction between the Rojava administration and the ‘terrorist’ pkk. But the ypg won the siege of Kobani and went on to expand the territory under its control.

Events in Syria thus helped undermine the dialogue between Turkish government representatives and the pkk that had been underway while a ceasefire was in force from 2013 to 2015. In this period, there were regular meetings involving government officials, an hdp delegation and, from his island prison, Abdullah Öcalan himself, along with other pkk members, which resulted in a ten-point roadmap for future negotiations that was made public in February 2015. But the trust needed to make the talks work was lacking after Kobani, and things only got worse during the June 2015 election campaign. The akp made the hdp its main target and sought to deny it parliamentary representation by keeping its vote below the 10 per cent threshold. This would have ensured a big majority in parliament for the akp, allowing it to impose the executive presidency that Erdoğan had been demanding. The ruling party’s desire to centralize power in its hands pushed many voters to side with the hdp for tactical reasons, as the only force that could prevent the akp from further eroding Turkey’s democratic institutions.

Backlash

Many hoped that the hdp’s success would pave the way for a negotiated settlement of the conflict with the pkk. But there were already clear signs that Erdoğan was unwilling to concede what was necessary to achieve this. In April 2015, he bluntly declared that the so-called Dolmabahçe Agreement, announced just two months earlier by hdp and Turkish government representatives, did not exist.footnote20 The akp still opposed Kurdish demands for autonomy and the constitutional recognition of their identity in Turkey, and Erdoğan was now infuriated by the result of the election, which had dented the akp’s prospects of consolidating its hegemony, already challenged on a number of fronts since the Gezi protests began. The Turkish president set out to build a new alliance with the ultra-nationalist mhp, based on repression of the Kurdish movement. The akp also sought to empower Kurdish Islamist forces such as the Hüda-Par, and groups affiliated with Masoud Barzani’s Kurdistan Democratic Party (kdp), a strong ally of Erdoğan and the akp.footnote21

This chauvinist turn was supercharged by the resumption of war between Turkish security forces and the pkk after the ceasefire collapsed in the summer of 2015. Erdoğan’s government deployed violence on a massive scale to repress any form of Kurdish dissent. The pkk’s external leadership, based in the Qandil mountains of northern Iraq, had been sceptical of Öcalan’s negotiations with the akp and responded to the government offensive with force.footnote22 In many ways the renewed conflict marks a return to the violence of the early 90s, with one notable difference: city-dwelling Kurds have been as badly affected as those living in the countryside. In the first half of 2016, the Turkish army targeted the pkk’s urban strongholds, reducing much of Diyarbakır’s old city to rubble and inflicting similar destruction on Şırnak, Cizre and Nusaybin. According to the unhcr, Turkish forces have killed hundreds of Kurdish civilians and are guilty of summary executions, torture and rape.footnote23 More than half a million Kurds have been driven from their homes. In response, a shadowy group known as tak (Kurdistan Freedom Falcons) carried out suicide bomb attacks targeting Turkish soldiers, police and civilians in the western cities, increasing tensions further.footnote24

Erdoğan’s approach to the Kurdish question in Turkey has also been strongly influenced by developments in Syria, as the akp fears that the consolidation of Kurdish self-rule in Rojava will permanently shift the regional balance in favour of the Kurds. The ypg armed units have played a central role in operations against isis, as part of the Syrian Democratic Forces that include some Arab militias, receiving military support and protection from the us as a result, which further complicates Turkey’s plan to contain Kurdish advances. However, the pyd has thus far been unable to secure political recognition from Washington, and is surrounded by hostile actors.footnote25 In August 2016, Turkish forces invaded northern Syria, ostensibly to clear isis out from positions along the border, but also determined to prevent the Kurdish forces from making further territorial gains. Air strikes targeting ypg units in Syria and around Iraq’s Mount Sinjar showed that Turkey was likely to carry out more cross-border operations against groups that it saw as pkk affiliates.

Against the backdrop of renewed conflict and hyper-chauvinist mobilization, with the funerals of Turkish soldiers and policemen broadcast on national television, a second general election was held in November 2015 to break the political deadlock. The akp set out to consolidate its Turkish-nationalist power base, gaining ground at the expense of the mhp to secure a parliamentary majority once again. The akp’s vote increased by almost 9 per cent, falling just short of 50 per cent overall. The hdp lost support but still managed to clear the 10 per cent threshold by a narrow margin. The party was vilified by government spokesmen and media outlets who presented it as a threat to Turkish democracy, and its offices were repeatedly attacked by nationalist mobs. Three weeks before the poll, two suicide bombers killed 109 people in Ankara at a peace rally called by the hdp and its allies. Police attacked the survivors with tear gas. isis was blamed for the attack, but hdp leaders also held the Turkish state responsible, accusing government agencies of colluding with the terrorists. One akp minister claimed that the hdp had staged the attack itself; a news anchor from a pro-government tv station suggested that ‘some’ of the victims may have been innocent (‘police officers, cleaning staff, passers-by or people trying to get to work’).footnote26

In the aftermath of the election, the akp set out to destroy the hdp’s institutional base, reviving the oppressive practices formerly used by the state against pro-Kurdish parties. In May 2016, parliament voted to strip hdp representatives of their immunity. Selahattin Demirtaş and his co-president Figen Yüksekdağ are currently being held in custody, along with some of the party’s most effective politicians (two other mps, Faysal Sarıyıldız and Tuğba Hezer, left Turkey to escape prosecution). In September 2016, a decree was passed allowing the government to remove elected mayors in the south-east and replace them with appointed officials. At time of writing, 85 mayors from the hdp’s sister party, the dbp, have been imprisoned. Charges brought against hdp politicians range from ‘carrying out propaganda for a terror organization’ to membership of the pkk itself, and prosecutors have demanded long prison sentences for them all. Approximately 6,000 hdp members are now under arrest. Erdoğan’s government has also targeted civil-society initiatives and the pro-Kurdish media. A group of more than 1,100 academics who signed a petition urging a peaceful approach to the Kurdish question have suffered persecution and administrative sanctions, with 360 removed from their posts so far. Turkish authorities have shut down the daily newspaper Özgür Gündem, forced hdp-supporting tv stations off the air, and accused 11,000 Kurdish and left-wing teachers who belong to the Education and Science Workers’ Union (Eğitim-Sen) of being pkk supporters, threatening them with the sack.

This authoritarian turn accelerated dramatically after the failed coup attempt of 15 July 2016. The akp has taken advantage of the opportunity to launch further attacks on its opponents, declaring a state of emergency for an initial period of three months, which has since been extended several times. With support from the mhp, Erdoğan’s party forced through its constitutional amendment for an all-powerful executive presidency and put it to a referendum in April 2017. In a climate of widespread violence and intimidation, with abundant evidence of vote-rigging, the reform was passed by a narrow margin: 51.4 to 48.6 per cent (10 per cent less than the combined vote share for the akp and mhp in November 2015). With the referendum victory, Erdoğan is now secure in the strong-man role that he has long craved, and his government’s repression of its opponents is likely to increase. However, given the small margin of Erdoğan’s victory and the widespread belief that it was obtained through fraud, a large section of Turkish society will remain opposed to the presidential system. It is also doubtful whether the autocratic power structure he wants to impose will bring stability or boost economic growth.footnote27

The hdp could challenge the dominant national-security discourse in Turkey when the conflict lay dormant, but with the renewal of fighting and the attendant restrictions on political debate, its message for peace does not resonate with much of the Turkish public. The party’s long-term health is linked to a peaceful resolution of the Kurdish question, and it is hard to imagine that it will be able to repeat its previous electoral successes in an environment characterized by violence and mounting authoritarianism. In the short term, it looks as if repression of the hdp will continue, and the party’s future role in Turkish politics will depend on its ability to survive under this pressure. The party has built up a strong organizational network and represents movements and political traditions that have a long and rich history of resistance; it has also cultivated strong ties to left-wing political forces in Europe, which means that it can mobilize international opposition to Erdoğan’s repression. Despite the ongoing persecution that it faces, the impact of the hdp’s political breakthrough is likely to resonate for a long time, in contrast to the Turkish left organizations that never recovered from the coup of 1980. That success brought to life a form of politics that few people in Turkey thought was possible, and stimulated the desire for a peaceful, multicultural and egalitarian country: a vital symbolic resource that will inspire those who follow in the hdp’s footsteps.