The Swedish Academy’s Praise for Its Prizewinners

Pascale Casanova has described the Nobel Prize for literature as ‘a unique laboratory for the designation and determination of what is universal in literature’. It is a setting where global interests converge, ‘one of the few truly international literary consecrations’. The annual award by the Swedish Academy may also serve to indicate, Casanova suggests, the existence of a world literary space riven by structural inequalities—the polar opposite of ‘literary globalization’, understood as a peaceful and progressive homogenization process.footnote1 The metaphor of the Nobel Prize as a laboratory for determining the canon is a striking one; its role in the standardization of literature and language, within a radically unequal literary world, has yet to be defined. Literal laboratories yield literal data—figures, tabulations, measures of a central tendency. In the study of world literature, we cannot marshal real-world test tubes or microscopes to discern the cultural and aesthetic assumptions driving the canon’s formation. However, working within figurative laboratories, we can apply methods of content analysis to yield qualitative and quantitative data that can be weighed and measured, helping us to track the movement of cultural capital through world-literary space. By analysing the official statements, bio-bibliographical sketches and award citations of the Swedish Academy, treated here as data to be counted and sorted, it may be possible to discern the tacit criteria—the political and cultural biases and values—underlying the annual consecration of Nobel laureates and the canonization it implies.footnote2

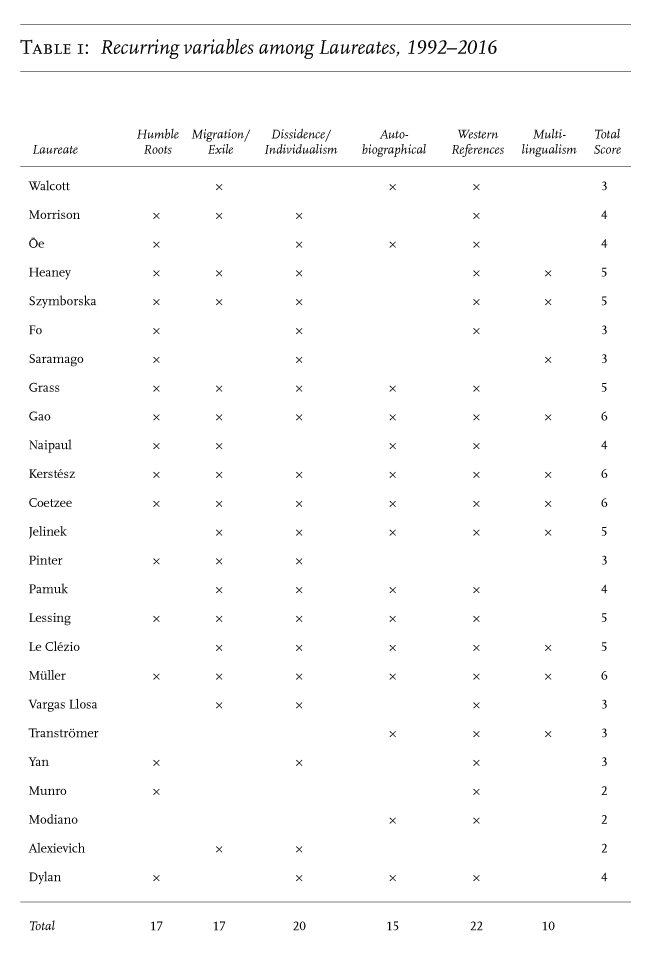

As the attempt to award the 2016 Prize to Bob Dylan showed, the Swedish Academy may be ultra-liberal in its considerations of literary forms and in curating a nationally diverse roster of laureates.footnote3 However, an examination of its official statements suggests that the Academy has consistently favoured a particular constellation of traits and life experiences, which Dylan’s character and oeuvre fit reasonably well. Certain words, phraseologies, ideologies, literary references and parallel life courses appear throughout its commentaries. I have isolated six such variables. Two of them—histories of exile and rising above humble roots—are common narrative lines in laureates’ personal histories. A third stresses the winning writer’s ideological leanings toward individualism and certain Academy-approved forms of revolution. A fourth is the nearly exclusive use of Western literary allusions in describing writers’ influences and work, even when laureates come from outside the Western tradition. The use of autobiographical content or inspiration is the fifth variable. Finally, there is the question of multilingualism. Non-English laureates are more likely to be multi-lingual than Anglophone winners, who typically have no professional literary credentials in any language but their own. This variable might have remained a curiosity, even a coincidence, were it not for the persistent and growing issue of English hegemony within world literature, especially with regard to translated texts such as those often used by the Swedish Academy.footnote4

context and methods

Regardless of founder Alfred Nobel’s instructions that the prize be awarded ‘with no consideration given to the nationality of the candidates’, and despite the Swedish Academy’s continuing claim that ‘national roots are irrelevant’ and that it does not recognize ‘what in Europe is often called the literary periphery’, identifiable national biases are visible throughout the Prize’s history.footnote5 Benedict Anderson has delineated three distinct periods within the lifespan of the Nobel Prize for Literature. The first, from 1901 to 1939, was characterized by domination by West European nations. Anderson identifies ‘regional favouritism’ within the Swedish Academy during this time in which one-third of the Prizes were awarded to Scandinavian writers, most of whom he does not consider ‘world-class’ authors. During the Cold War era, the international scope of the Nobel Prize extended to literatures all over the globe. Still noticeably snubbed, however, was Russian or Soviet literature: of the four Russian writers rewarded in this period, three were vocally opposed to the Soviet government. Moscow responded by insisting Boris Pasternak decline the Nobel Prize after Dr Zhivago was banned by the regime. Anderson’s final period begins at the end of the Soviet era in 1991. During this time, the Academy has achieved its most global perspective to date—perhaps thereby inspiring enough confidence and self-satisfaction to make it more prone to unintended biases.footnote6

Adopting Anderson’s periodization, I have concentrated on the post-Cold War era, beginning in 1992. I examined the Swedish Academy’s official bio-bibliographical statements and its citations at awards ceremonies, identifying keywords and concepts as recurring variables.footnote7 When these appeared, the laureate in question was coded as positive for that variable. Scores were tabulated, assigning numerical values to how many variables each of the laureates typified (Table 1, below). These reflect how well each writer fitted the ideal profile of a Nobel Prize for Literature laureate. It is, of course, important not to confuse these findings from the biographies and award citations with statements of fact about the laureates. The data here simply reflect what the Academy says, not whether it is justified or even factually accurate.

Also not analysed here are gaffes the Academy makes, revealing its Western-centrism and propensity to Orientalize when it speaks of ‘the spiritual poverty of Trinidad’ in V. S. Naipaul’s biography; describes Derek Walcott’s background as ‘a meeting between European virtuosity and the sensuality of the Caribbean’; reduces Svetlana Alexievich’s journalism to a metaphor about a ‘stenographer’; compliments Orhan Pamuk on being ‘Western enough to have the method to portray’ what he knows from his Eastern sensibilities; speaks of the modern Chinese history Mo Yan writes about as ‘life in a pigsty’; or generally fails to relate to Toni Morrison’s work without becoming mired in references to the whiteness around the black lives she authors, persisting in speaking of them not as subjects but as ‘companion’, ‘racial other’ and ‘shadow’.footnote8 These remarks are important and telling, yet they fall outside the scope of this analysis which is limited to the six recurring variables defined above—humble roots, migration and exile, revolutionary politics and individualism, autobiographical content, Western literary allusions, and multilingualism.

findings

In terms of sheer demographics, the last twenty-five years of Nobel Prize for Literature laureates have been predominantly male. Eighteen men (72 per cent) have received the award, which has gone to women only 7 times (28 per cent) during the same period. By far the greatest proportion of laureates—17 out of the 25 (68 per cent)—were residents of Europe at the time of their awards. Five laureates lived in the Americas (20 per cent), 2 in Asia (8 per cent), 1 in Australia (4 per cent) and none at all in Africa. The most common language was English, the working language of 9 of them (36 per cent). Used by 4 laureates, German was the second most common (16 per cent). Though the term can be problematic to define, by any criteria the majority of the laureates were not people of colour.

As shown below, the six variables isolated in the Nobel Prize’s official statements were represented to some degree in all 25 of the laureates.

The table below shows for which variables each laureate was coded as positive, along with their scores and the total number of times each variable was noted.

To see how these variables unfold, and what they may reveal of the Academy’s underlying values for selecting laureates, we will now consider each in turn.

Humble roots

Most of the biographical notes of the post-Cold War era Nobel laureates—20 out of 25—begin with a mention of the occupations, social status or homes of the writer’s parents and forebears. In 17 out of these 20 mentions, the Swedish Academy’s accounts of laureates’ early lives and family histories are told in ways that emphasize hardship, either within writers’ family lives or in the greater historical context of their formative years. Many of the laureates have overcome adversity ranging from unfortunate to unimaginable. Due to his Jewish ancestry, a teenaged Kertész was imprisoned in Auschwitz and Buchenwald. Morrison was a little girl inside her parents’ house when their landlord set it on fire after they fell behind on their rent. Lessing truly was a stenographer for a time. Saramago trained as a mechanic after he no longer had the financial means to finish high school. Struggles like these are worth recounting.

However, even when a writer enjoyed a fairly privileged upbringing, the Academy’s biographical notes will sometimes reach to give a sense of the writer springing heroically from humble roots. For instance, Naipaul is an Oxford alumnus and the son of a writer who encouraged and inspired him in his own work. These are rare and excellent advantages for a developing writer but are mentioned by the Academy only in passing before moving on to emphasize Naipaul’s ties to his immigrant, plantation-worker grandfather. Similarly, Coetzee is acknowledged as the son of a teacher and an attorney, yet the Academy, perhaps mindful that being raised by parents with professions that sound stable and reliable might be too ordinary, adds a line to the author’s biography, explaining in vague terms that his father practiced law ‘only intermittently’.footnote9 This undermining of stories that might read as staid and stable may reveal a preference among the Academy for casting itself in the role of elevating the downtrodden, actively avoiding the image of being an elite organization crowning fellow elites.

It must be observed that the Academy has been forthcoming with details of privilege enjoyed by its laureates in their early lives. Pamuk’s family is described as prosperous, and Ōe is acknowledged as ‘the scion of a prominent samurai family’. Still, while Ōe’s social position was prestigious, the struggles of the whole of Japanese culture during the years following World War II are highlighted in his biography, bringing a downcast hue to his Nobel profile in spite of the status he enjoyed. According to the Academy, events surrounding Japan’s surrender were ‘shocking . . . for the young Ōe’ and brought on a sense of ‘humiliation’.footnote10 Ōe’s youth is characterized as a time of humbling and debasement. The same could be said for Gao, whose early life conditions are described as ‘the aftermath of the Japanese invasion’ of China. Nothing in particular is said of how this affected young Gao, but the implication of hardship is clear.footnote11 Stories of overcoming difficulty, or at least of bearing with the ennui of mediocre surroundings, are part of what constitutes the preferred romantic figure of a Nobel laureate.

Migration and exile

Migration is another recurring theme in laureates’ life stories as told by the Swedish Academy, though this can involve being forced into exile, or flight from the threat of incarceration, as well as simply moving house.footnote12 Seven of the 25 laureates underwent voluntary migration by themselves or with their parents. Mobility is often described in warm clichés, such as when Mario Vargas Llosa was called a ‘citizen of the world’—a phrase used in a slightly different form two years earlier when Le Clézio was called a ‘nomad of the world’. The Academy praised Naipaul as ‘cosmopolitan’, his ‘lack of roots’ presented as fertile artistic ground.footnote13 Naipaul’s award citation explicitly reminds us that this preference for the peripatetic lifestyle extends directly from founder Alfred Nobel’s personal philosophy.footnote14

Seven more Nobel laureates experienced mandatory, sometimes violent relocations. Gao came to France from China as ‘a political refugee’. In the same category is Alexievich, who has lived throughout Europe because ‘her criticism of the regime’ meant she could not remain in her homeland. Grass’s biographical note refers to his ‘captivity by American forces’ following World War II.footnote15 Müller’s mother, Kertész and Pinter all suffered deportations or evacuations related to the same war. Lessing and Fo were not forced to leave their homes; however, they were barred from travelling to certain countries due to views expressed in their work. Mobility under duress is recognized by the Swedish Academy as a source of artistic insight and inspiration, handled with the reverence due to human suffering. Four of the Nobel biographies, which may or may not include stories of writers having to flee into exile themselves, contain the word ‘exile’ or a synonym of it, such as ‘outcast’. This suggests that exile is valued by the Academy not only as an element of a writer’s history, but as a theme in the work of writers from any background. Writers may be recognized not only for their own factual exile but also for the exiles of the populations represented in their work, such as Le Clézio’s interest in writing about ‘those who live in our societies without belonging to them’.footnote16

Individualism and dissidence

The most commonly shared factor among the 25 Nobel laureates of the post-Cold War period is their being controversial, individualistic, dissident figures. For many, revolt is not only literary but literal. Their work is ‘esthetical as well as political’ in its significance.footnote17 Ideal Nobel laureates are politically active, writing texts levelling criticisms at the status quo, challenging authority and hierarchy, calling for societal changes. Perhaps most importantly, these calls always come with a cost to the writers who make them. Some, like Kertész and Saramago, sacrificed their jobs when their employers’ politics became unbearable. ‘I believe’, Szymborska agrees, ‘in the ruined career’.footnote18 Others, like Fo and Lessing, risked their abilities to travel and work in certain countries including, for Fo, the massive market of the United States. Müller emigrated from Romania when she was censored and ultimately prohibited from publishing there. Rather than silence herself, she went into exile.

Not all revolutionary writers can flee when they need to: Gao burned a suitcase of manuscripts as a safeguard against persecution in China during the Cultural Revolution. Thousands of Vargas Llosa’s books were publicly burned by officers from a military school he had depicted in a novel. Jelinek was able to stay and work in Austria but is described by the Academy as ‘a highly controversial figure in her homeland’. In a rather heady moment, the Swedish Academy revelled in the pleasure it takes in social justice to the point of calling Coetzee ‘a Truth and Reconciliation Commission on [his] own’.footnote19 Regardless of overblown rhetoric, enthusiasm for the revolutionary stances and statements of the majority of the post-Cold War Nobel laureates reveals the Academy’s sense that art is worthier when it strikes beyond the internal, private scope. Ideal Nobel laureates find themselves in positions to antagonize authorities, working to change the way they and those around them understand and live in the world.

However, the Academy is not indiscriminate, and does not reward any and all revolutionary inclinations. It is vocally enamoured with the principle of individualism. The word ‘individual’, along with related terms like independence, appears in roughly half of all the laureates’ biographies and award citations. Before lauding Kertész’s work for celebrating ‘an individual’s refusal to abandon his individual will by merging it with a collective identity’, the Academy rails against ‘the bureaucratic, misanthropic stupidity of the socialist one-party state [which is] hardly comprehensible to minds that have been shaped in civilized societies’.footnote20 It extends this distaste to East Asian nations where social values tip toward collectivism rather than individualism. Gao, a dissident, is praised for his ‘vivid sense of alienation’ and his work’s depiction of ‘man’s [sic] urge to find the absolute independence granted by solitude’ within the social context of a large, populous society that depends on ‘obedience and conformity’. Of all the Chinese nationals who could have been honoured, the Academy made a laureate out of Yan, a writer it admires for ‘tear[ing] down stereotypical propaganda posters, elevating the individual from the anonymous human mass’. In Gao, the Academy consecrated a Chinese dissident, provoking protest from the government in Beijing, which disowned Gao, calling him a ‘French writer’.footnote21 In Yan, the Academy recognized a Chinese national but one with controversial politics, satirical material and a personal philosophy of individualism pleasing to Western sensibilities. The Academy has proved however, that on occasion it can reach out of its ideological comfort zone to anoint laureates whose politics it finds unsettling. In Saramago’s biography we read that he joined the Communist Party, but are quickly assured that, when it came to this revolutionary affiliation, Saramago ‘has always adopted a critical standpoint’.footnote22

Autobiography and allusions

For 15 of the 25 laureates considered here, the Swedish Academy lays stress on the autobiographical nature of their work. Perhaps, in the same vein as the Academy’s respect for the suffering enfolded in its laureates’ humble roots and dissident activities, the Academy can more easily justify its choices when a laureate has paid a personal, painful price that is explicitly referred to in their work. Even when the events depicted in a writer’s work are not factual, the Academy will frame them as autobiographical after a fashion. It does so with Kertész, explaining that his work is ‘based on his experiences’ while warning ‘this does not mean, however, that [the work] is autobiographical in any simple sense’. The Academy also repeats Modiano’s claim that his ‘memory preceded his birth’ and speaks of his novels set during France’s wartime occupation, before Modiano himself was born, as ‘autobiography merge[d] with fiction’.footnote23 As in other areas, we see the Academy reaching to extend the use of its key, ideal terms to situations where a stricter interpretation—‘a simple sense’—of those meanings may not apply. This adds credence to the argument that the ideal romantic figure of a Nobel laureate is constructed not only by the writers who arrive as exemplars of it, but by the Academy itself as it tailors its characterizations of its laureates to suit pre-existing ideals.

All but two of the Nobel laureates in the period in question have references to other artists included in their biographies and awards citations. These other artists may be mentioned as having had an influence, or for their likenesses to laureates’ work. Several writers are named more than once. William Faulkner is mentioned most often, with Thomas Mann, Joseph Brodsky, Edgar Allan Poe, Dante and Homer tying for second place. Of the dozens of literary influences mentioned during the post-Cold War period by the Swedish Academy, all but one are from the West (the exception is R. K. Narayan, recognized as important to Naipaul). Moreover, when the Swedish Academy does mention the salience of Eastern literature and traditions, it lays down its practice of stringing together lists of proper names of individuals and reverts to general categories. For instance, comments on Gao include broad references to Daoism and Confucianism as venerable old ideologies, never in terms of individual Daoist or Confucian writers or thinkers. Likewise, it is said of Yan that his work ‘finds a departure point in old Chinese literature’, but no mention is made of specific authors, texts or oral tales. The pattern holds when the writers in question are from the Western tradition but have gained followings in the East. In speaking of Tranströmer, the Academy extolls him as ‘one of the very few Swedish writers with an influence on world literature’. It names Joseph Brodsky as an admirer of his, and goes on to speak in vague plural about Tranströmer’s role as a model ‘among Chinese poets’—none of whom are named.footnote24 Whatever else, this represents a missed opportunity for the Swedish Academy, whose stated mandate is to advance world literature irrespective of nationality. To illuminate non-Western influences could have shown that the Academy was in earnest about regarding all cultures as equal and worthy. Devoting time and resources to unpacking, for example, ‘the mystic tradition of the East’ that it finds in Pamuk’s writing, would be a more convincing demonstration of the Nobel committee’s world perspective than anything the Academy could repeat from Nobel’s will.

Multilingualism

As Georg Brandes has observed, writers of different countries and languages occupy enormously different positions in so far as their chances of obtaining worldwide fame, or even a moderate degree of recognition, are concerned.footnote25 To what extent are Nobel laureates expected to show their relevance to world literature through proficiency in multiple languages—and are Anglophone writers, working in what may be considered world literature’s lingua franca, held to the same standard as the rest? If the Nobel Prize is, as Casanova has described it, a ‘laboratory for the designation and definition of what is universal in literature’, any differences might serve to strengthen the hegemony of English in what is already, no matter which model of world literature one prefers, an unequal global literary landscape.

As we’ve seen, of the 25 laureates considered here, 9 wrote in English, with German the second most common language, used by 4 of the laureates. French appears twice, as does Chinese. Swedish, Russian, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Turkish, Polish and Japanese appear only once. Among the laureates, there are 10 who are identified as multilingual, indeed qualified and experienced in translating. The remaining 15—a majority—were decorated by the Academy despite not working in multiple languages. Using translator status to gauge the influence of English hegemony is clearly complicated, especially with a dataset as small as this. However, the composition of this subset of 10 translator-laureates is telling. Of the 10, only Coetzee and Heaney work primarily in English; Coetzee translates Dutch and Afrikaans, Heaney classical Greek. Three of the four German laureates are recognized by the Academy as translators, and all the translator-laureates except Coetzee live in Europe. Gao, a native of China now living in France, is the only East Asian laureate to work as a translator.

All in all, half (50 per cent) of the non-Anglophone laureates have been translators, as opposed to only 22 per cent of those who write in English. The latter can, as Stephen Owen has put it, ‘work in blithe self-confidence regarding the universal adequacy of [their] linguistic community’ and their typically limited language capacities.footnote26 Differences are further deepened when laureates’ genders enter the calculations. None of the three English-speaking women translate, though three of their four non-English counterparts do so (but less than half of non-English male laureates). Is it possible that non-English women must enhance their appeal to the Swedish Academy by working in multiple languages? Our dataset is too small to tell.

conclusion

Based on the analysis here, the typical Nobel Prize for Literature laureate in the post-Cold War era is a male novelist working in a language from the Anglo-Germanic family. He is ethnically European and probably lives on that continent. He is a risk-taker, an individualist, the right kind of rebel. He has risen to international prominence from humble (or at least unremarkable) roots. His work has been influenced by, or can be compared to, that of named Western artists; if it also reveals non-Western influences, these will not be specified. His art is inspired by events in his own life. He is probably not a translator. These findings would seem to reinforce Casanova’s cautions about an ‘ongoing unification of literary space’ within the ‘laboratory’ of the Nobel Prize for Literature.footnote27 Though the Swedish Academy is willing to risk variations in form—drawing outrage by awarding the Prize to a songwriter—its enduring preference for standard story-types and themes, not just in the work of the writers it consecrates but also in their life courses, is discernible in its official statements and award citations.

Of course, the stated ideals of the Academy remain openness and divergence. In a terse 2013 question-and-answer session, Peter Englund, then Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy, addressed the question, ‘How do you find authors worthy of a Nobel Prize in Literature?’ Englund answered: ‘It is not difficult to find worthy candidates. There are many: the world is so big . . . the hard part is to select who will get it.’footnote28 It is easier, it seems, to go about choosing ‘the best in the world’ if the field is largely limited to those who conform to the Swedish Academy’s tropes of struggling artists, in rebellion against regimes the Academy dislikes, writing of their own experiences with inferred reference to the Western canon, exemplifying cosmopolitanism and favouring individualism over collectivism. As Casanova puts it, the circulation of cultural capital through world literary space should be understood not simply as a post-national ‘pacification’ process—the ‘progressive normalization and standardization of themes, forms, languages and story-types across the globe’—but acknowledged as a series of ‘collisions’, ‘struggles, rivalries and contests over literature itself’.footnote29