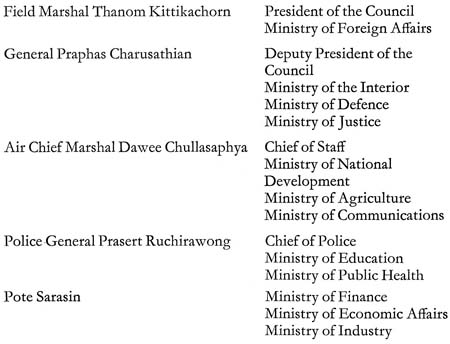

On 17 November, 1971, the praetorian clique that has ruled Thailand for the past 13 years declared a total military dictatorship, less than one month after General Lon Nol had made a similar declaration in Cambodia. This was not a surprising step; it was indeed a logical one in the face of increasingly antagonistic contradictions within Thai society. It should be seen against the background of the crisis of the ruling classes in Indochina since the turning point of the 1968 Tet offensive, the subsequent Nixon doctrine, and the admission of China to the un on 25 October, 1971. The Thai constitution has been abrogated; the cabinet and both houses of the National Assembly dismissed; and military law established throughout the country. The King of Thailand, a shadow head of state manipulated without much show of unwillingness by the military, is reported as having given his blessing to the dictatorship. The composition of the ‘National Executive Council’, and Ministries controlled by the military junta are indicated below:

Since the abolition of the absolute monarchy in 1932, Thailand has had 15 governments, mostly headed by right wing military, 8 more or less bloodless coups and 8 constitutions. But this should not mislead one into thinking that the recent putsch is merely a historical repetition. The military have never been so blatant; the people, conventionally considered politically apathetic, contented and loyal, have never been so politically conscious nor so liable to become radically disillusioned; the strength of active, including armed, opposition to the ruling classes has never been so great; the importance of Thailand to external powers, in this case the usa, has never been so crucial. Hence the stakes are higher, the antagonisms sharper for all concerned.

The military clique has predictably justified its new concentration of power in terms of a national emergency and the need to defend national interests and security; that is, the interests and security of the ruling classes. But the interests of the military and civilian sections of the ruling bloc do not fully coincide. For the past eight years, Field Marshal Thanom has been able to reconcile these divergent factions in an administration in which key political posts were held largely by the military elite, while specialized executive posts were filled by a civilian technocracy, which had become steadily more detached from the mass of the people, recruiting from within its own ranks and educated almost entirely abroad, usually in the usa. For the past three years, sensing which way the wind was blowing, the civilian elite, including a few genuinely nationalist and democratic liberals, have become increasingly outspoken: on the dangers of the Thai-American alliance; the grievances of the masses; the decline of traditional Thai culture; and so on. There has been much pressure for reform (e.g. against corruption), for parliamentarism (a general election was held in February 1969 for the first time in 12 years), and for a more flexible, more traditionally ‘Siamese’ foreign policy. There was a growth of trade with East European, though not Asian, socialist countries, and openings towards China were investigated sub-diplomatically (e.g. meetings with Pridi Phanomyong, an exiled, left-wing former Prime Minister). When China was admitted into the un (with Thailand voting opportunistically in favour), there was considerable pressure from the Thai-Chinese dominated Board of Trade for private trade with the People’s Republic. This accumulation of liberalizing tendencies did not suit the military elite; it had more to lose from these than anyone, and it had become so entrenched in its policies and corrupt style of government that no flexibility could be expected to redeem it. It also already feared the cold wind of a possible American ‘withdrawal’. By the time of the coup even Thanat Khoman, civilian Foreign Minister for 13 years, and at times more bellicose than American generals, but also at times

The military section of the ruling bloc thus felt threatened on a number of fronts and appears to have analysed the dangers quite logically in terms its own interests, though in public statements it has shifted its emphasis for tactical reasons. External dangers included what appeared to it or what could be made to appear to its public as a lessening of American support, military, economic and diplomatic. With the admission of China to the un, it was feared that the Chinese population of Thailand might transfer its loyalty and support to the widespread and effective armed opposition to the government. On the internal front the government was also threatened by, on the one hand various manifestations of social discontent, such as an increasing crime rate, student violence and strikes; and on the other, by parliamentary opposition, including that within the ranks of its own party. This latter form of opposition was perhaps the most immediately significant. It hampered day-to-day administration, undermined the government’s public facade of legality and respectability, and threatened to thwart the regime’s plan to continue in office under General Praphas after the February 1973 parliamentary election, by which time Field Marshal Thanom was to have retired. Each of these factors now needs more careful analysis.

At the February 1969 elections the ‘government party’ as it was known, the so-called ‘United Thai People’s Party’ (utpp), failed to obtain a majority of seats; and in the vast constituency of Bangkok won not a single seat, despite greatly superior organizational and financial resources, and some illegal tactics. A precarious plurality was obtained by buying most of the ‘independent’ candidates (for sums around $20,000). Not only did the new parliament begin to work quite effectively in criticizing government policy and administration, proving not merely a ‘rubber stamp’ or ‘debating chamber’ as had been expected, but serious divisions developed within the utpp as client members demanded money (in the order of $100,000 each) in order to exercise in turn their own patronage within their constituencies, make good some electoral promises and try to ensure their re-election. This precarious parliamentary base seemed unlikely to provide the support needed for success in the February 1973 election. This was especially so since Marshal Thanom had announced that he would resign as Prime Minister before then and hand over to General Praphas, a far less subtle politician; despite a certain gangster charisma, he was unlikely to command the loyalty of many middle-of-the-road voters. Thus the coup, in which Praphas undoubtedly played the major role, can be seen as anticipating a troubled succession.

Since 1950 the us government has poured billions of dollars of mostly military aid into Thailand and constructed a network of strategic roads and bases in Thailand. These are linked to the great Uttapao/Sattaheep

The Thai ruling classes have an ambivalent attitude towards this American presence. They have made enormous killings from American military expenditure; have received guarantees of United States help against internal and external enemies; and have thereby built up a military and economic power base for themselves without having to oppress the masses as much or as directly as they would otherwise have had to do. At the same time the American presence has been seen, by all except the most cynical, to have had a devastating effect on the morale and culture of the Thai people (an effect which is perceived as a servile relationship with a technically and financially superior barbarian, and epitomized in the phenomenon of large-scale prostitution). But until recently the short-term advantages far outweighed any disadvantages. Since the Nixon doctrine however, American self-interest and exploitation has been seen even more clearly for what it is. American ground troop reductions mean that Asians have to do the dirty work and the dying. Troop reductions in Thailand from 50,000 to 32,000 by mid 1971 were planned, though this new lower level has still not been reached, and in meetings with us Ambassador Unger after the coup, the military asked for further delays. Even the figure of 32,000 contains 26,000 air force troops, so that the usa is not thereby decreasing its air war against Indochina. Thus Thailand continues to bear the opprobrium of being host to the American aggressor, whose presence encourages revolution at home, while being less certain of receiving the kind of military support it considers will be necessary to suppress the increased armed opposition within its own frontiers. It is also evident that the Thai Army will have to do more of the fighting itself.