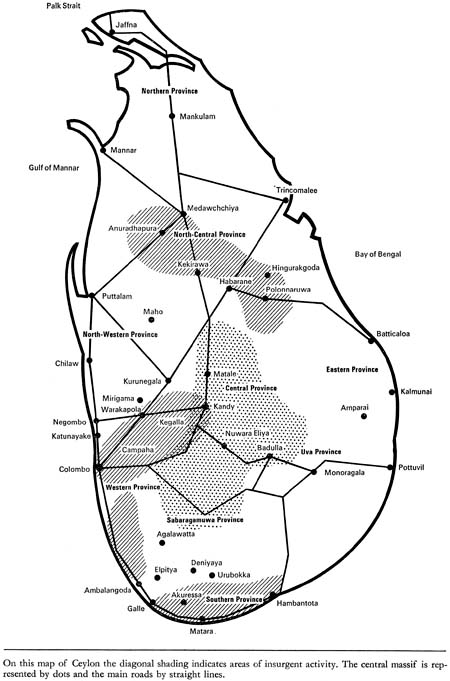

In April 1971 a revolutionary insurrection exploded in Ceylon. Unanticipated by imperialism, and unexpected by revolutionaries elsewhere, sections of the rural masses rose in organized rebellion against the very government they had voted into power in the previous May. This upsurge marks a totally new phase in the hitherto relatively tranquil history of the Ceylonese state. But the insurrection also has an importance far beyond the coasts of Ceylon itself. A brief resumé of the political situation in which it exploded will indicate its astounding and unique character. The government against which the people rose had come to power on a verbally ‘anti-imperialist’ and ‘socialist’ platform, and included representatives of the pro-Moscow Communist Party and the ex-Trotskyist Lanka Sama Samaj Party. It was generally regarded in imperialist circles as a dangerous and dogmatically left-wing régime. Secondly, the resistance to this government did not take the form of fragmented and spontaneous resistance, nor of organized strikes, nor even of initial low-level guerrilla actions: it assumed the form of a widespread armed insurrection, the most advanced and most complex from

The Ceylonese insurrection was also strategically of great significance for the revolutionary movement in Asia as a whole. In the past twelve months, Great Power rivalry in the Indian Ocean has been on the increase, while popular wars in the Gulf (Oman) and Eritrea have consolidated and advanced. The Ceylonese insurrection came a month after the defeat of the invasion of Laos, and coincided with the popular resistance to Yahya Khan in Bengal. It thus formed part of creeping social conflagration throughout the Asian continent and represented the opening of a new social revolutionary front, in between East Asia and West Asia, at a nodal point where the economic and strategic interests of imperialism had previously appeared to be secure. It is not yet possible to give a full analysis of the Ceylonese events of this year: they are still too close. What follows is an attempt to grasp the specificity of recent Ceylonese history, and the nature of the present economic and social crisis in the island, which gave birth to the jvp and the astonishing insurrection of April 1971.

Ceylon is a small tropical island, of some 25,000 square miles, separated by a narrow defile of water from the Indian subcontinent. It is divided into different regions by both topography and climate. The whole coastal rim, and the northern and eastern interior, form a flat lowland; in the south-centre, however, a high massif rises sheer above the plains to dense, forested peaks of over 7,000 feet. Overlapping this division is an extremely sharp climatic contrast between a triangular wet zone in the south-west corner of the island, with heavy rainfall, fertile land and irrigated cultivation, and a dry zone haunted by drought and scrub, which occupies the whole of the north and east of the island. In the early pre-colonial epoch, much of this was watered by extensive hydraulic systems, and formed the homeland of the Ancient Sinhalese kingdoms which vied with the Tamil states in the far north of the island. The network of tanks, dams and canals had, however, fallen into disuse and decay well before the arrival of European conquerors; and, as a consequence, the centre of Sinhalese culture and society had shifted southwards to the highlands of Kandy in the south-west. It was in the latter zone that cinnamon was collected wild in the jungles: this

Ceylon underwent a longer historical experience of colonization than any other country in Asia. It bears the marks of this past—some 450 years of European domination—to this day. The Portuguese invaded the island in 1505, and rapidly conquered the coastal lowlands, isolating but not subjecting the Kandyan kingdom in the fastnesses of the south-central highlands. They established a rudimentary but effective trading control over the island, exploiting it for the collection of wild cinnamon, of which Ceylon then had a world monopoly. In the succeeding 150 years they also succeeded in converting a relatively high proportion of the Sinhalese population in the south-western coastal strip, centred on Colombo, to Catholicism, thereby dissociating them both culturally and economically from the Sinhalese in the beleaguered Kandyan uplands. A singular mark of the Portuguese impact on the low-country Sinhalese was their mass adoption of Lusitanian names. To this day, De Souza, Perera, and Gomes proliferate in the south-west: a phenomenon whose only parallel in Asia is to be found in the Philippines, where the Spanish monastic frailocracia achieved an even more spectacular success in formally converting and hispanizing the indigenous population. Portuguese rule, however, came to an end in 1658, when the Dutch seized their territories in the island in collusion with the Kandyan nobility, during the long Ibero-Dutch wars of the 17th century. The new rulers developed and modernized the economic system bequeathed to them by their predecessors. The Dutch cinnamon economy was now based on organized plantations, in which production was rationalized and yields increased. The blockade of the unsubdued highlands was tightened, and the social and political system of late Kandyan feudalism gradually disintegrated within the ring of Dutch forts and settlements which surrounded it. Holland was not interested in mass conversion of the local population, given the more pronouncedly particularist and racist character of Protestantism: but it did introduce the peculiar system of Roman-Dutch law which has survived in the island down to the present.

Another 150 years later, Ceylon underwent its third European conquest. Once again, it fell to a new colonial master as a by-blow of international conflicts within Europe itself. The formation of the Batavian Republic in Holland in 1795, ally and client of the Directory in Paris, led to a British attack on Ceylon as part of England’s worldwide counter-revolutionary and imperialist offensive against the French Revolution and its sequels. Kandyan feudalism collaborated with the British expeditionary forces as eagerly and short-sightedly against the Dutch, as it had with the Dutch against the Portuguese. Once the Dutch had been evicted, London proceeded to complete the unfinished work left by Amsterdam. In 1815, the British fomented a revolt by the Kandyan aristocracy against the last Kandyan monarch and marched into the uplands to depose him at their request. Two years later, when the same nobility rose against British rule in a fierce rebellion in which their villagers participated heroically, they were crushed by the occupiers they had themselves invited into their remote redoubts.

The import of Tamil labour levelled off in the 20th century, leaving a social and ethnic configuration in Ceylon which has fundamentally determined the subsequent character and course of class struggle there. It can now be summed up as follows. footnote2 70 per cent of the population are Sinhalese. They are concentrated in the south and centre of the island, and are themselves divided into ‘low-country’ and ‘Kandyan’ Sinhalese, according to their region of residence and date of conquest by European colonialism; the latter were naturally much less deeply affected than the former, and have preserved traditionalist superstructures (religion and kinship) more jealously. The bulk of the Kandyan Sinhalese are subsistence peasants, cultivating rice in small plots in the upland valleys. Colonial rule, however, by no means wiped out the traditional ruling class which had squeezed this peasantry with its oppressive exactions before conquest. A grasping neo-feudal stratum of aristocratic and clerical landowners, chieftains and monks, retained sizeable holdings and dominated village life, which was steeped in reactionary Buddhist superstitions. This stratum was re-cruited in the upper Goyigama caste and wielded immemorial local power. Keeping to its paddy estates, it did not participate much in the cash-crop agriculture established by the British. The low-country Sinhalese, by contrast, who outnumbered the Kandyan Sinhalese by some 3 to 2, had been exposed to three centuries more European rule: their social structure was consequently far more hybrid. While many subsistence villages remained relatively untouched, large numbers of low-country Sinhalese were inducted into the coconut and rubber plantations, while others formed the nucleus of the urban working class that developed in Colombo and other ports in the island. At the same time, the commercialization of coastal agriculture by the British created new opportunities for the privileged, who had long acquired some of the basic skills for profiting from colonial rule, under the Portuguese and Dutch. Thus low-country landowners participated on a significant scale in the development of the rubber sector, and rapidly dominated the coconut zone. A business élite based on local commerce burgeoned in Colombo. Many of these wealthy and powerful low-country Sinhalese were recruited from the Karawa caste (originally linked to fishing, and hence well below the Goyigama in the caste scale), and were Roman Catholics with Portuguese cognomens. They sedulously imitated and parodied the culture and customs of their British overlords. They were flanked by the small community of descendants from the Portuguese and Dutch themselves, the ‘Burghers’, who formed an arrogant Eurasian minority in the towns.

The Tamil population of Ceylon, for its part, is even more divided than the Sinhalese. Numerically, it is equally distributed between the so-called ‘Ceylon Tamils’, who are overwhelmingly the majority community in the Northern Province of the island, and extend in strength down the east coast, and the so-called ‘Indian Tamils’, who are clustered on the plantations of the central massif. The ‘Ceylon Tamils’ are those who have resided in the island from its