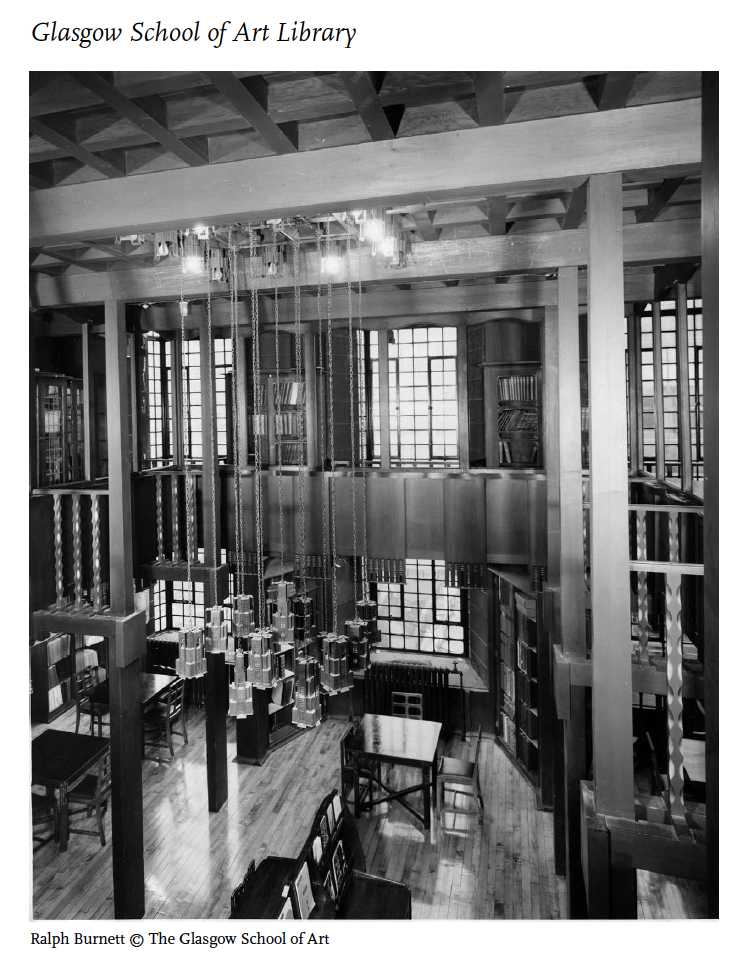

The library at Glasgow School of Art has—or had—special status for connoisseurs of the work of architect-artist Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Its ineffably graceful timbers garnered a totemic value as a symbol of the workaday genius of their creator. It was said that this exquisite room could be created by any competent craftsman under instruction from the architect’s drawings; no special craft skills were needed. Indeed in the aftermath of the fires that destroyed Mackintosh’s masterwork and all its contents in 2014, and again in 2018, the School authorities claimed, evidently by way of reassuring those connoisseurs and others, that the Library would be rebuilt ‘as Mackintosh designed it, to the millimetre’—‘It is absolutely coming back.’footnote1

The implicit suggestion—and indeed often the explicit claim at the time—was thus that Mackintosh’s conceptions, or in other words, his models in the form of architectural drawings, are the real art, and the physical manifestation of that graphical genius in the timbers of the Library can be recreated by any joiner the School cares to appoint. We might then begin to wonder about that relationship between the drawings and the materially constructed Library, whereby Mackintosh’s very plans seem to operate like some type of magical incantation, and take possession of the hands of a dayjobbing tradesman to conjure them into the execution of a work of supreme artistic merit. This might in turn bring us to ask if, in the post-fires era of destruction, the Library does, in fact, still exist? The actual timbers of the room are gone, but those plans, the original prime movers in the creation of the space, and the formulae that will be used to put the material version back into place—they still exist. So what is the relative ontological status of these two components, which both have some evident claim to be Mackintosh’s Library? Can the Library still exist after it has been destroyed by fire? Does its putative totemic status indeed entail something of a magical, or fantasy, ideal or utopic quality, something beyond those everyday material qualities already annihilated twice in the fires?

Perhaps it is best to address that question of the Library’s existence after its physical material has been annihilated by establishing first what apparently it is not—a mere material artefact. The locus classicus for modes of existence of things is of course Aristotle, particularly in the Metaphysics. In his work to shift philosophy away from mathematics and abstract universal substance and towards the physical sciences, and the concrete individual substance, Aristotle’s principle that a thing cannot both be and not be at the same time plays a central role.footnote2 So can a thing be annihilated by a conflagration and still exist? It depends on what you mean by ‘thing’ and what kind of existence it has.

As hinted above, some intellectual insight into a special type of existence, exhibited by this Mackintosh work, might then be gained by viewing it in terms of typology—an abstracted universal which can be asserted of the substance of works of architecture. The typology is said, in the case of Mackintosh’s two-storey, timber, galleried room, to be a library. Libraries are of course one of the few remaining types of sequestered space in the heart of our cities where a free engagement in cultural, political and intellectual life can be pursued, both at a social and an individual level, apparently at no cost. Is that range of possible operations itself sufficiently idyllic to define it as a working utopia? Or are there other more fundamental properties necessary for a place to have such a privileged ontological status?

As a member of staff at Glasgow School of Art, I had often taught in the Mackintosh Library (pre-2014), read in it, led tours around it. I had written about it in several publications and been filmed there by crews from around the world. In one piece for Architectural Research Quarterly I described the Library as ‘one of the most delicate and evocative spaces in Western architecture’.footnote3 Two days after the 2014 fire, I was able to inspect the damaged Mackintosh building. Working with a team of colleagues, under the direction of the Fire Brigade and gsa’s architects, I helped to retrieve some half-burnt and charred artefacts from the less-damaged rooms. The collective sense of heartbreak was palpable as we worked in those blackened, gloomy ruins in an air thick with acrid stench from the fire.

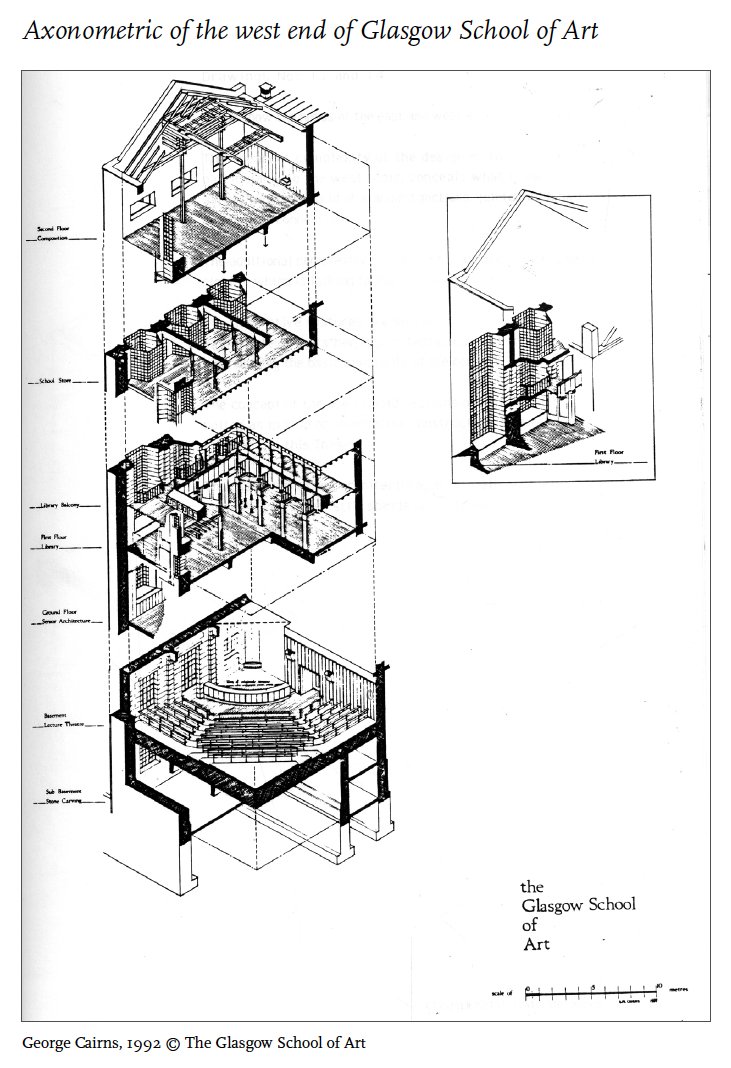

You might imagine then my joy when, nearly four years later, in mid-April 2018, I entered the almost completely rebuilt Mackintosh Library. Some of the materials needed to reconstruct the room in accordance with the early twentieth-century ‘original’ had been difficult to find. The timber, for example—a now rare tulipwood—had been sourced from an old sawmill building in Massachusetts that was being demolished. Yet actual material, and age and source of the material, notwithstanding, the feel of the place was substantially the same as I had remembered experiencing in the original up until 2014. My delight on entering the recreated Library was doubled by seeing it mirrored in my companion’s face. George Cairns, who in the early nineties had completed his doctorate on the Mac, and had produced some of the most detailed drawings of this place, was on a visit from Australia.footnote4 This tour had been arranged specially for him. His appreciation of the building was especially poignant because Cairns had raised his voice—early on after the 2014 fire—as one of those Ruskinian modernists in favour of a completely new library, and he was absolutely against the attempt to recreate the old one from Mackintosh’s ‘original’ designs.footnote5

The qualities or even the very existence of the reproduction—if it were thus—evidently seemed to elicit joy even in those who had been flatly against any form of reproduction taking place. Was that delight in Cairns’s face testimony of a triumph of sensual stimulation from physical reality over the intellectual satisfaction afforded by presenting oneself as a model of ideological or moral purity? It’s difficult to say, for my own delight, redoubled by its reflection in my guest’s eyes, was further complicated and compromised by a set of more complex reactions which I simultaneously underwent.

These reactions might be compared to those described by Freud in his short article ‘A Disturbance of Memory on the Acropolis’.footnote6 Freud, who had studied Classics as a boy attending the Gymnasium in Vienna, visited Athens for the first time as a tourist with his brother when he was 48 years old. Where he had expected that he would experience only pleasure on visiting the Acropolis, he discovered that his delight was tempered by a sort of astonishment that the monument actually existed. It was as though he had always doubted the real existence of the Ancient Greek site, and it was only now, under the impact of unequivocal observation, that he realized, first of all, that it really did exist, and secondly, that he had been unaware that its real existence, of which he had heard so much as a schoolboy, had ever been an object of doubt.

There I stood, in a similar twist of emotions in the almost-completed recreation of the Mackintosh Library, amazed that the physical construct actually existed. As for that ‘feel’ of the space: the timbers reproduced the same room; there was a bodily memory of orientation in space, in relation to forms and objects, in the quality and direction of light—an imprinting of spatial configurations, an understanding of perceptions and possible movements and their consequences. Notwithstanding the absence of aging patina and colour on the timbers, and a number of missing final details, like the chamfered balusters, this was undeniably the Mackintosh Library and would be to anyone who had ever experienced the ‘original’. Yet like Freud on the Acropolis, my delight—and indeed, redoubled delight—was mixed with an awkward feeling of astonishment at the reality of this physical recreation. I realized that, alongside my celebration and delight at this achievement, I must have doubted all along that it would ever have been possible to convert the ruined and hollowed-out stone shell of 2014 back into that ‘delicate and evocative’ timber room. But had I actually ‘doubted’, and if so, why had I not been aware that I was doubting, during the four years that the rebuild was in process only yards from my own office? Freud refers to this feeling as one of ‘derealization’, whereby the ego, to protect itself from a great joy which it feels it does not deserve, disavows the historical reality. Accordingly, ‘derealization’ is counterposed by Freud to the phenomenon of déjà vu: the latter seeks to incorporate something other and alien as if it were already a part of the ego; derealization seeks to deny something ever belonged to the ego, to disavow or cast doubt upon it.

If that analysis of Freud’s is to be taken literally, however, then relief was close at hand. For the ego, which was beset with an overwhelming, unbearable and, in the Freudian schema, undeserved joy, was to be saved by a second disaster: the fire of June 2018. Just as the Library had almost miraculously reappeared, four years after its reduction to a pile of black ash, so in that 2018 fire, two months after its epiphany in timber, it was sublimated completely in the flames. The Library, which had existed first as a set of drawings in the 1890s, and then as a physical entity in timber and other materials, disappeared in the fire of 2014, to exist once more only in ink and paper; had then been reproduced in material again by 2018; and finally, once more disappeared in flames to leave only a set of charts with markings in pencil and coloured inks.

Measured Space

The disappearance of the library again in 2018 may have been shockingly unexpected, but the ‘derealization’ of its forms by an embodied visitor, as Freud might term it, is not of course a new way of viewing the world; nor are such doubts about the form of existence of the sensible world something originally encountered in Freud. The history of Western thought, as everyone knows, is riven with such a dualism—arguably most acutely expressed in the method of Cartesian doubt, where all one’s sensory experience of the real world is to be treated with scepticism until any aspect of it is proved certain. But if, for Descartes, we can only be certain of that physical world through the measurement and calculation of its extension, its modelling in complex analytical geometry and algebra, mapping every place in the universe back to the zero point of the subject—Cartesian geometry, in other words—then Mackintosh’s Library, designed as an intricate network of upright and horizontal timbers, dividing space, framing views and precisely parcelling out and directing qualities of light and shade, performs a similar orienting and centring of the subject in calculated and measured space.

From that point of view, it might be fruitful to understand the operation of the library—as equally Descartes’s mathematics—as a type of apparatus, that is, as a formation which seeks to support and to determine or orientate certain behaviours, gestures, opinions or discourses; and which is therefore fundamentally involved in the process of subjectification. Agamben defines an ‘apparatus’ in terms of three important aspects: as a network between elements—which may be linguistic, physical, legal, juridical or conceptual—that has a strategic function and stands at the intersection of power and knowledge.footnote7 Since its original appearance around 5,000 years ago, the typology of ‘the library’ has been a key device in the apparatus of human subjectification, inasmuch as it encourages certain relations with knowledge, and imposes, via its structures, certain dispositions in approaches to and uses of that knowledge.

Mackintosh refined the structure of the library as a physical network so that the criss-crossing of verticals (uprights, hanging lamps, pendants and furniture legs) and horizontals (beams, balconies, surfaces of tables and chairs) frames every single point of the room with specific spatial qualities and a unique play of light. Accordingly the visitor, the reader, the student—in other words the subject—enters into a space saturated with order and identity and is predisposed to certain attitudes and understandings of the place; and, as noted, the recreation of these forms in early 2018 was ‘undeniably’ as particular as the original in its presentation of possible and special perceptions and bodily orientations.

The particular identity of the Library is indeed often analogized to a natural phenomenon. Like his younger contemporary, James Joyce (1882–1941), Mackintosh (1868–1928) is said to have created his masterwork in the form of a Gaelic forest.footnote8 The architect Thomas Howarth, Mackintosh’s biographer, was the first to make this explicit, likening the Library to ‘silent brooding pinewoods of the Trossachs’. Yet there is more to it than a throwaway qualitative comparison of atmosphere and light. In Mackintosh’s case, the form is specifically appropriate for a library full of the written word, as each of the eighteen letters of the Gaelic alphabet corresponds to the name of a tree: A, B, C are ailm, beith, coll—in turn, the elm, the birch and the hazel. Hence the library is in Gaelic culture literally a forest. Joyce’s creation of the city as a forest in Ulysses is a linguistic model.footnote9 Likewise Mackintosh’s creation of the library as a forest exists as a linguistic model in the form of architectural drawings, essentially ink on paper like Joyce’s model; it has also existed between 1909–2014 and for a few months in early 2018, as an actual place. The appearance and disappearance of the Library heightens the tension of the relationship between the linguistic model and the material reality that we already see in Joyce’s Ulysses.

For some understanding of that relationship, we can turn again to Descartes and his example of the kiliagon, the thousand-sided figure of which we can construct a mathematical model, and make accurate calculations of its properties in terms of number of sides, lengths, size of angles, etc., even though the figure has no concrete reality for us.footnote10 Perhaps an even more vivid exposition of the model–reality relationship is to be found, however, in Foucault’s discussion of the mirror.footnote11 The images in the mirror have a peculiar ontological status; they present us with apparent and calculable spatial relations in terms of lengths, depth and breadth, orientation and relationships between objects, colour, movement, speed and so on, as studied in the field of optics. Yet, of course, all this information is presented on one silvered surface; there is no actual space there—or as Foucault puts it, it is a place with no real place. The image in the mirror and Descartes’s theoretical figure of the kiliagon thus confound Aristotle’s principle that something cannot at the same time both be and not be. It is no coincidence that Foucault’s assessment of the ontological status of the images in the mirror chimes almost perfectly with the tension introduced in Thomas More’s erstwhile neologism of 1517 for his book Utopia, the playful name of which incorporates in its Greek etymology both ‘a good place’ and ‘no place’: utopia is somewhere which both exists and does not exist at the same time. Indeed, Foucault himself categorizes the ‘space’ in the mirror as a ‘utopia’.

The serial appearance and disappearance of the Mackintosh Library as a material place allows us to see it more certainly and specifically in the tradition of the Gaelic utopia. The pastiche Hollywood version of this tradition as ‘Brigadoon’, the elusively ‘perfect’ Scottish village that makes an actual appearance once every hundred years before disappearing again into the mists of time, is well known. The vicissitudes of Mackintosh’s library bring it closer, however, to the original saga or orature model of the deep-sleeping Fenian warriors and heroes and their return from below the earth every few centuries to save the Gaelic race and civilization.

The doubt—in real time—about the relationship between the model and an actual place remains unresolved. How many times can the physical Mackintosh Library re-appear to perform its role as an apparatus in organizing relationships to knowledge at Glasgow School of Art? And if all apparatuses, from the library to the products of the Hollywood film industry—and indeed, to language itself—ultimately fail to secure certain knowledge of the real, and vacillate in a most un-Aristotelianly dubious way between being and non-being, then is not their default mode by definition utopian? Or as Agamben puts it, ‘At the root of each apparatus lies an all too human desire for happiness.’footnote12