The world is abuzz with talk of automation. Rapid advances in artificial intelligence, machine learning and robotics seem set to transform the world of work. In the most advanced factories, companies like Tesla have been aiming for ‘lights-out’ production, in which fully automated work processes, no longer needing human hands, can run in the dark. Meanwhile, in the illuminated halls of robotics conventions, machines are on display that can play ping-pong, cook food, have sex and even hold conversations. Computers are not only developing new strategies for playing Go, but are said to be writing symphonies that bring audiences to tears. Dressed in white lab coats or donning virtual suits, computers are learning to identify cancers and will soon be developing legal strategies. Trucks are already barrelling across the us without drivers; robotic dogs are carrying military-grade weapons across desolate plains. Are we living in the last days of human toil? Is what Edward Bellamy once called the ‘edict of Eden’ about to be revoked, as ‘men’—or at least, the wealthiest among them—become like gods?footnote1

There are many reasons to doubt the hype. For one thing, machines remain comically incapable of opening doors or, alas, folding laundry. Robotic security guards are toppling into mall fountains. Computerized digital assistants can answer questions and translate documents, but not well enough to do the job without human intervention; the same is true of self-driving cars.footnote2 In the midst of the American ‘Fight for Fifteen’ movement, billboards went up in San Francisco threatening to replace fast-food workers with touchscreens if a law raising the minimum wage were passed. The Wall Street Journal dubbed the bill the ‘robot employment act’. Yet many fast-food workers in Europe already work alongside touchscreens and often earn better pay than in the us.footnote3 Is the talk of automation overdone?

i. the automation discourse

In the pages of newspapers and popular magazines, scare stories about automation may remain just idle chatter. However, over the past decade, this talk has crystalized into an influential social theory, which purports not only to analyse current technologies and predict their future, but also to explore the consequences of technological change for society at large. This automation discourse rests on four main propositions. First, workers are already being displaced by ever-more advanced machines, resulting in rising levels of ‘technological unemployment’. Second, this displacement is a sign that we are on the verge of achieving a largely automated society, in which nearly all work will be performed by self-moving machines and intelligent computers. Third: automation should entail humanity’s collective liberation from toil, but because we live in a society where most people must work in order to live, this dream may well turn out to be a nightmare.footnote4 Fourth, therefore, the only way to prevent a mass-unemployment catastrophe is to provide a universal basic income (ubi), breaking the connection between the incomes people earn and the work they do, as a way to inaugurate a new society.

This argument has been put forward by a number of self-described futurists. In the widely read Second Machine Age (2014), Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee argue that we find ourselves ‘at an inflection point—a bend in the curve where many technologies that used to be found only in science fiction are becoming everyday reality.’ New technologies promise an enormous ‘bounty’, but Brynjolfsson and McAfee caution that ‘there is no economic law that says that all workers, or even a majority of workers, will benefit from these advances.’ On the contrary: as the demand for labour falls with the adoption of more advanced technologies, wages are stagnating; a rising share of annual income is therefore being captured by capital rather than by labour. The result is growing inequality, which could ‘slow our journey’ into what they call ‘the second machine age’ by generating a ‘failure mode of capitalism’ in which rentier extraction crowds out technological innovation.footnote5 In Rise of the Robots (2015), Martin Ford similarly claims that we are pushing ‘towards a tipping point’ that is poised to ‘make the entire economy less labour-intensive.’ Again, ‘the most frightening long-term scenario of all might be if the global economic system eventually manages to adapt to the new reality’, leading to the creation of an ‘automated feudalism’ in which the ‘peasants would be largely superfluous’ and the elite impervious to economic demands.footnote6 For these authors, education and retraining will not be enough to stabilize the demand for labour in an automated economy; some form of guaranteed non-wage income, such as a negative income tax, must be put in place.footnote7

The automation discourse has been enthusiastically adopted by the jeans-wearing elite of Silicon Valley. Bill Gates is advocating for a tax on robots. Mark Zuckerberg told Harvard undergraduate inductees that they should ‘explore ideas like universal basic income’, a policy Elon Musk also thinks will become increasingly ‘necessary’ over time, as robots outcompete humans across a growing range of jobs.footnote8 Musk has been naming his SpaceX drone vessels after spaceships from Iain M. Banks’s Culture Series, a set of ambiguously utopian science-fiction novels depicting a post-scarcity world in which human beings live fulfilling lives alongside intelligent robots, called ‘minds’, without the need for markets or states.footnote9

Politicians and their advisors have equally identified with the automation discourse, which has become one of the leading perspectives on our ‘digital future’. In his farewell presidential address, Obama suggested that the ‘next wave of economic dislocations’ will come not from overseas trade, but rather from ‘the relentless pace of automation that makes a lot of good, middle-class jobs obsolete.’ Robert Reich, former Labour Secretary under Bill Clinton, expressed similar fears: we will soon reach a point ‘where technology is displacing so many jobs, not just menial jobs but also professional jobs, that we’re going to have to take seriously the notion of a universal basic income.’ Clinton’s former Treasury Secretary, Lawrence Summers, made the same admission: once-‘stupid’ ideas about technological unemployment now seem increasingly smart, he said, as workers’ wages stagnate and economic inequality rises. The discourse has become the basis of a long-shot presidential campaign for 2020: Andrew Yang, Obama’s former ‘Ambassador of Global Entrepreneurship’, has penned his own tome on automation, The War on Normal People, and is now running a futuristic campaign on a ‘Humanity First’, ubi platform. Among Yang’s vocal supporters is Andy Stern, former head of the seiu, whose Raising the Floor is yet another example of the discourse.footnote10

Yang and Stern—like all of the other writers named so far—take pains to assure readers that some variant of capitalism is here to stay, even if it must jettison its labour markets; however, they admit to the influence of figures on the far left who offer a more radical version of the automation discourse. In Inventing the Future, Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams argue that the ‘most recent wave of automation is poised’ to transform the labour market ‘drastically, as it comes to encompass every aspect of the economy’.footnote11 They claim that only a socialist government would actually be able to fulfil the promise of full automation by creating a post-work or post-scarcity society. In Four Futures, Peter Frase thoughtfully explores the alternative outcomes for such a post-scarcity society, depending on whether it still had private property and still suffered from resource scarcity, which could persist even if labour scarcity were overcome.footnote12 Like the liberal proponents of the automation discourse, these left-wing writers stress that, even if the coming of advanced robotics is inevitable, ‘there is no necessary progression into a post-work world’.footnote13 Srnicek, Williams and Frase are all proponents of ubi, but in a left-wing variant. For them, ubi serves as a bridge to ‘fully automated luxury communism’, a term originally coined in 2014 by Aaron Bastani to name a possible goal of socialist politics, and which flourished for five years as a meme on the internet before his book—outlining an automated future in which artificial intelligence, solar power, gene-editing, asteroid mining and lab-grown meat generate a world of limitless leisure and self-invention—finally appeared.footnote14

Recurrent fears

These futurist visions, from all points of the political spectrum, depend upon a common prediction of the trajectory of technological change. Have they got this right? To answer this question, it is helpful to have a couple of working definitions. Automation may be distinguished as a specific form of labour-saving technical innovation: automation technologies fully substitute for human labour, rather than merely augmenting human-productive capacities. With labour-augmenting technologies, a given job category will continue to exist, but each worker in that category will be more productive. For example, adding new machines to an assembly-line producing cars may make line workers more productive without abolishing line work as such. However, fewer workers will be needed in total to produce any given number of automobiles. Whether that results in fewer jobs will then depend on how much output—the total number of cars—also increases.

By contrast, automation may be defined as what Kurt Vonnegut describes in Player Piano: it takes place whenever an entire ‘job classification has been eliminated. Poof.’ No matter how much production might increase, another telephone-switchboard operator or hand-manipulator of rolled steel will never be hired. In these cases, machines have fully substituted for human labour. Much of the debate around the future of workplace automation turns on an evaluation of the degree to which present or near-future technologies are labour-substituting or labour-augmenting in character. Distinguishing between these two types of technical change turns out to be incredibly difficult in practice. One famous study from the Oxford Martin School suggested that 47 per cent of jobs in the us are at high risk of automation; a more recent study from the oecd predicts that 14 per cent of oecd jobs are at high risk, with another 32 per cent at risk of significant change in the way they are carried out (due to labour-augmenting rather than substituting innovations).footnote15

It is unclear, however, whether even the highest of these estimates suggests that a qualitative break with the past has taken place. By one count, ‘57 per cent of the jobs workers did in the 1960s no longer exist today’.footnote16 Automation, in fact, turns out to be a constant feature of the history of capitalism. By contrast, the discourse around automation, which extrapolates from instances of technological change to a broader social theory, is not constant; it periodically recurs in modern history. Excitement about a coming age of automation can be traced back to at least the mid-19th century. Charles Babbage published On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures in 1832; John Adolphus Etzler’s The Paradise Within the Reach of All Men, Without Labour appeared in 1833, Andrew Ure’s The Philosophy of Manufactures in 1835. These books presaged the imminent emergence of largely or fully automated factories, run with minimal or merely supervisory human labour. This vision was a major influence on Marx, whose Capital, Volume One argued that a complex world of interacting machines was in the process of displacing labour at the centre of economic life.

Visions of automated factories then appeared again in the 1930s, 1950s and 1980s, before their re-emergence in the 2010s. Each time, they were accompanied or shortly followed by predictions of a coming age of ‘catastrophic unemployment and social breakdown’, which could be prevented only if society were reorganized.footnote17 To point out the periodicity of this discourse is not to say that its accompanying social visions should be dismissed. For one thing, the technological breakthroughs presaged by automation discourse could still be achieved at any time: just because they were wrong in the past does not necessarily mean that they will always be wrong in the future. More than that, these visions of automation have clearly been generative in social terms: they point to certain utopian possibilities latent within modern capitalist societies. The error in their approach is merely to suppose that, via ongoing technological shifts, these utopian possibilities will imminently be revealed via a catastrophe of mass unemployment.

The basic insight on which automation theory relies was described, most succinctly, by the Harvard economist Wassily Leontief. He pointed out that the ‘effective operation of the automatic price mechanism’ at the core of capitalist societies ‘depends critically’ on a peculiar feature of modern technology, namely that in spite of bringing about ‘an unprecedented rise in total output’, it nevertheless ‘strengthened the dominant role of human labour in most kinds of productive processes’.footnote18 At any time, a breakthrough could destroy this fragile pin, annihilating the social preconditions of functioning market economies. Drawing on this insight—and adding only that such a technological breakthrough now exists—the automation prognosticators often argue that capitalism must be a transitory mode of production, which will eventually give way to a new form of life that does not organize itself around work for wages and monetary exchange.footnote19

Taking its periodicity into account, automation theory may be described as a spontaneous discourse of capitalist societies, which, for a mixture of structural and contingent reasons, reappears in those societies time and again as a way of thinking through their limits. What summons the automation discourse periodically into being is a deep anxiety about the functioning of the labour market: there are simply too few jobs for too many people. Proponents of the automation discourse consistently explain the problem of a low demand for labour in terms of runaway technological change.

Declining labour demand

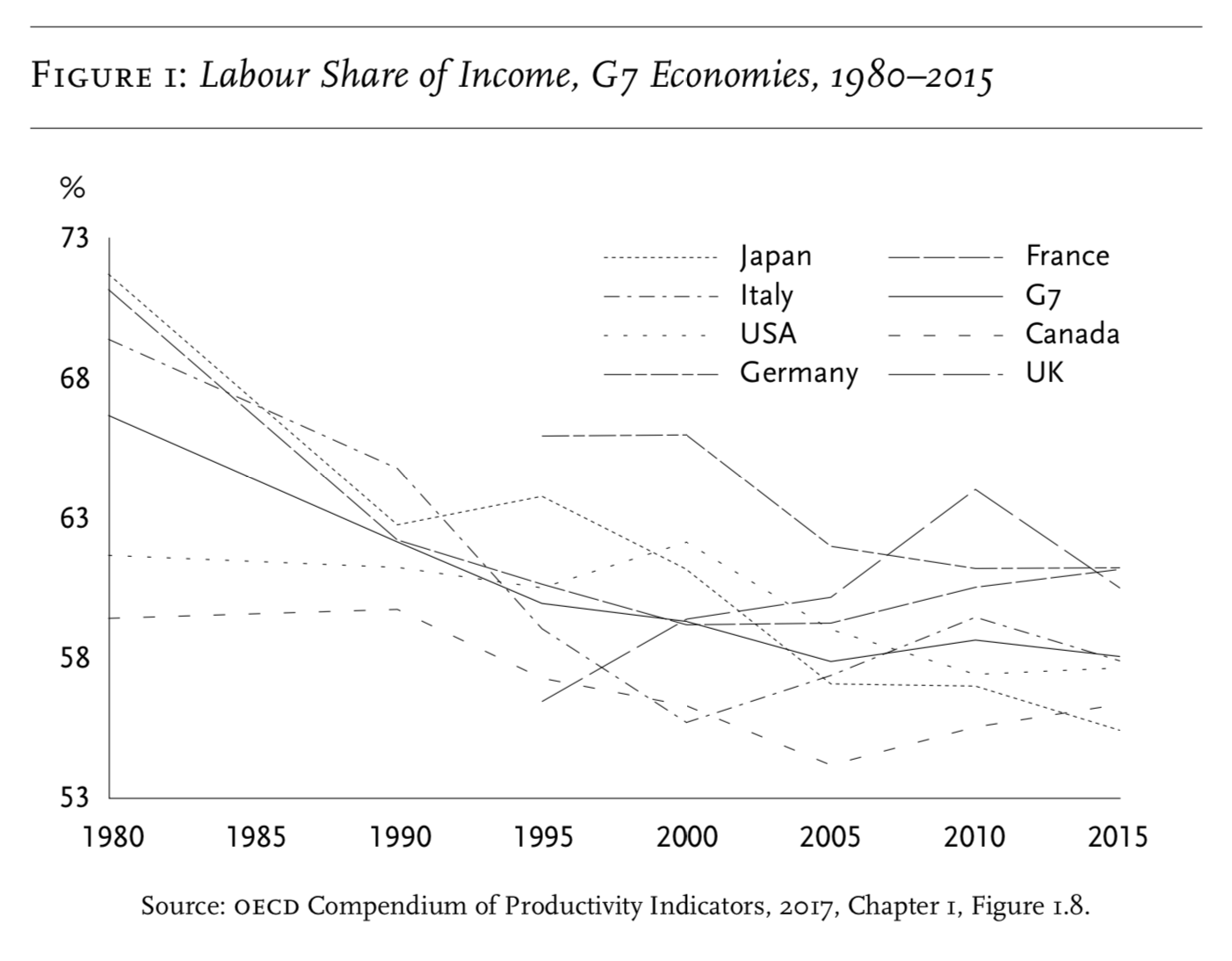

If automation discourse appeals so widely again today, it is because, whatever their causes, the ascribed consequences of automation are all around us: global capitalism clearly is failing to provide jobs for many of the people who need them. There is, in other words, a persistently low demand for labour, reflected not only in higher spikes of unemployment and increasingly jobless recoveries—both frequently cited by automation theorists—but also in a phenomenon with more generic consequences: declining labour shares of income. Many studies have now confirmed that the labour share, whose steadiness was held to be a stylized fact of economic growth, has been falling for decades (Figure 1).

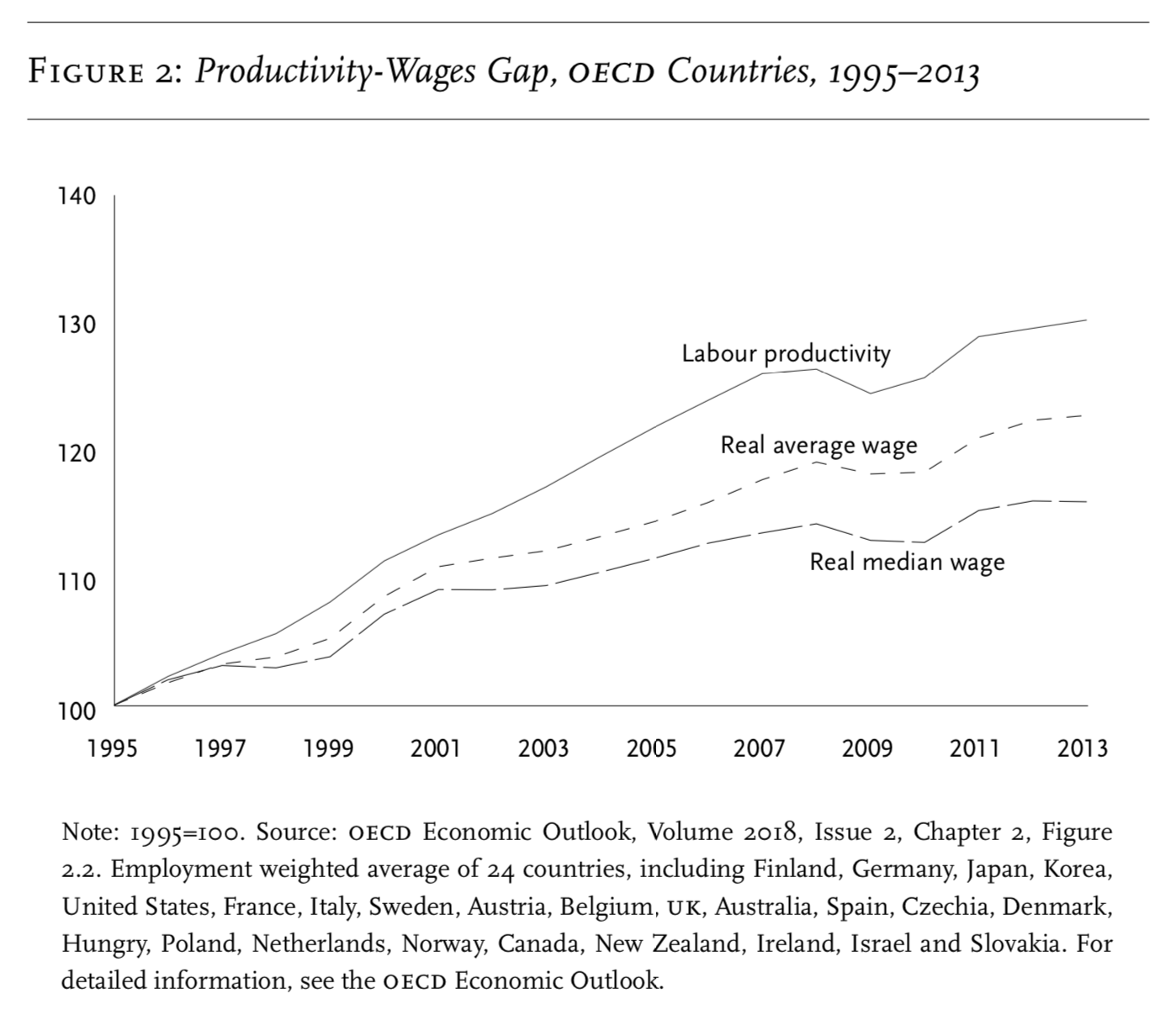

These shifts signal a radical decline in workers’ bargaining power. Realities for the typical worker are worse than these statistics suggest, since wage growth has become increasingly skewed towards the highest earners: the infamous top one per cent. A growing gap has opened up not only between the growth of labour productivity and average wage-incomes, but also between the growth of average wages and that of median wages, with the result that many workers see a vanishingly thin slice of economic growth (Figure 2).footnote20 Under these conditions, rising inequality is contained only by the strength of redistributive programmes. Even critics of automation discourse such as David Autor and Robert Gordon are disturbed by these trends: something has gone wrong with the economy, leading to a low demand for labour.footnote21

Is automation the cause of the low demand for labour? I will join the critics of automation discourse in arguing that it is not. However, along the way, I will also criticize the critics—both for producing explanations of low labour demand that only apply in high-income countries and for failing to produce anything like a radical vision of social change that is adequate to the scale of the problems we now confront. Indeed, it should be said from the outset that I am more sympathetic to the left automation theorists than to their critics.

Even if the explanation they offer turns out to be inadequate, the automation theorists have at least focused the world’s attention on the problem of a persistently low demand for labour. They have also excelled in actually trying to imagine solutions to this problem that are broadly emancipatory in character. In Jameson’s terms, the automation theorists are our late capitalist utopians.footnote22 In a world reeling from the ‘perfect storm’ of climate change, rising inequality, recalcitrant neoliberalism and resurgent ethno-nationalism, the automation theorists are the ones pushing through the catastrophe with a vision of an emancipated future, in which humanity advances to the next stage in our history, whatever that might mean (or whatever we want to make it mean), and technology helps to free us all to discover and follow our passions. That is true in spite of the fact that—like many of the utopians of the past—the actual visions these latest utopians offer need to be freed from their largely technocratic fantasies of how social change to a better future might take place.

Major shifts in the forms of government intervention in the economy are adopted only under massive social pressure, such as, in the course of the 20th century, the threat of communism or of civilizational collapse. Today, policy reforms could emerge in response to pressure coming from a new mass movement, aiming to change the basic makeup of the social order. Instead of fearing that movement, we should see ourselves as part of it, helping articulate its goals and paths forward. If that movement is defeated, maybe the best we will get is basic income, but that should not be our goal. We should be reaching towards a post-scarcity world, which advanced technologies will certainly help us realize, even if full automation is not achievable—or even desirable.

The return of automation discourse is a symptom of our era, as it was in times past: it arises when the global economy’s failure to create enough jobs causes people to question its fundamental viability. The breakdown of this market mechanism today is more extreme than at any time in the past. This is because a greater share of the world’s population than ever before depends on selling its labour or the simple products of its labour to survive, in the context of weakening global economic growth. Our present reality is better described by near-future science-fiction dystopias than by standard economic analysis; ours is a hot planet, with micro-drones flying over the heads of the street hawkers and rickshaw pullers, where the rich live in guarded, climate-controlled communities while the rest of us wile away our time in dead-end jobs, playing video games on smartphones. We need to slip out of this timeline and into another.

Reaching towards a post-scarcity world—in which all individuals are guaranteed access to whatever they need to make a life, without exception—can become the basis on which humanity mounts a battle against climate change. It can also be the foundation on which we remake the world, creating the conditions in which, as James Boggs once put it, ‘for the first time in human history, great masses of people will be free to explore and reflect, to question and to create, to learn and to teach, unhampered by the fear of where the next meal is coming from’.footnote23 Finding our way forward requires a break between work and income, as the automation theorists recognize, but also between profit and income, as many do not.

In responding to the automation discourse, then, I will argue that the decline in the demand for labour is due not to an unprecedented leap in technological innovation, but to ongoing technical change in an environment of deepening economic stagnation. In the second part of this contribution, to be published in nlr 120, I contend that this fall in labour demand manifests not as mass unemployment, but rather as mass under-employment, not necessarily a problem for the elites. On this basis, I mount a critique of technocratic solutions, like basic income. I offer a thought-experiment of how we might imagine a post-scarcity society that centres on humans, not machines, and project a path of how we might get there through social struggle, rather than administrative intervention. But first, in Part One, I provide a diagnosis of the underlying causes of the decline in demand for labour. This involves a detour to consider the fortunes of the global manufacturing sector and the competitive dynamics at work in labour’s ‘deindustrialization’.

2. labour’s global deindustrialization

Automation-discourse theorists recognize that, if technologically induced job-destruction is to have widespread social ramifications, it will have to eliminate employment in the vast and variegated service sector, which absorbs 74 per cent of workers in high-income countries and 52 per cent worldwide.footnote24 They therefore focus on ‘new forms of service-sector automation’ in retail, transportation and food services, where ‘robotization’ is said to be ‘gathering steam’ with a growing army of machines that take orders, stock shelves, drive cars and flip burgers. Many more service-sector jobs, including some that require years of education and training, will supposedly be rendered obsolete in the coming years due to advances in artificial intelligence.footnote25 Of course, these claims are mostly predictions about the effects that technologies will have on future patterns of employment. Such predictions can go wrong—as for example when Eatsa, an automated fast-food company which employed neither cashiers nor waiters, was forced to close most of its stores in 2017.footnote26

In making their case, automation theorists often point to the manufacturing sector as the precedent for what they imagine is beginning to happen in services—for in manufacturing, the employment-apocalypse has already taken place.footnote27 To evaluate the theorists’ claims, it therefore makes sense to begin by looking at what role automation has played in that sector’s fate. After all, manufacturing is the area most amenable to automation, since on the shop floor it is possible to ‘radically simplify the environment in which machines work, to enable autonomous operation’.footnote28 Industrial robotics has been around for a long time: the first robot, the ‘unimate’, was installed in a General Motors plant in 1961. Still, until the 1960s, scholars studying this sector were able to dismiss Luddite fears of long-term technological unemployment out of hand. Manufacturing employment in fact grew most rapidly in those lines where technical innovation was happening at the fastest pace, because it was in those lines that prices fell the fastest, stoking the growth of demand for the products.footnote29

Industrialization has long since given way to deindustrialization, and not just in any one line but across the manufacturing sectors of most countries.footnote30 The share of workers employed in manufacturing fell first across the high-income world: manufacturing employed 22 per cent of all workers in the us in 1970; that share declined to just 8 per cent in 2017. Over the same period, manufacturing employment shares fell from 23 per cent to 9 per cent in France, and from 30 per cent to 8 per cent in the uk. Japan, Germany and Italy have experienced smaller but still substantial declines: in Japan from 25 per cent to 15 per cent, in Germany from 29 per cent to 17 per cent, and in Italy from 25 per cent to 15 per cent. In all cases, the declines were eventually associated with substantial falls in the total number of people employed in manufacturing. In the us, Germany, Italy and Japan, the overall number of manufacturing jobs fell by approximately a third from postwar peaks; in France, by 50 per cent and in the uk, by 67 per cent.footnote31

It is commonly assumed that deindustrialization must be the result of production facilities moving offshore. Yet in none of the countries named above has manufacturing job loss been associated with declines in manufacturing output. Real value added in manufacturing more than doubled in the us, France, Germany, Japan and Italy between 1970 and 2017. Even the uk, whose manufacturing sector fared worst of all among this group, saw a 25 per cent increase in manufacturing real value added over this period. To be sure, low- and middle-income countries are producing more and more goods for import into high-income countries; however, deindustrialization in the latter cannot simply be the result of productive capacity moving to the former. In the scholarly literature, deindustrialization is therefore ‘most commonly defined as a decline in the share of manufacturing in total employment’, regardless of corresponding trends in levels of manufactured output.footnote32 This definition moves in step with automation theorists’ core expectations: more goods are being produced but by fewer workers.

It is on this basis that commentators typically cite rapidly rising labour productivity, rather than an influx of low-cost imports from abroad, as the primary cause of industrial-job loss in advanced economies.footnote33 On closer inspection, however, this explanation turns out to be inadequate: no upward leap has taken place in manufacturing productivity levels.footnote34 On the contrary, manufacturing productivity has been growing at a sluggish pace for decades, leading Robert Solow to quip, ‘We see the computer age everywhere, except in the productivity statistics.’footnote35 Automation theorists discuss this ‘productivity paradox’ as a problem for their account—explaining it in terms of weak demand for products, or the persistent availability of low-wage workers—but they understate its true significance. This is partly due to the appearance of steady labour-productivity growth in us manufacturing, at an average rate of around 3 per cent per year since 1950. On that basis, Brynjolfsson and McAfee suggest, automation could show up in the compounding effects of exponential growth, rather than an uptick in the growth rate.footnote36

However, official us manufacturing growth-rate statistics are overinflated, for example in logging the production of computers with higher processing speeds as equivalent to the production of more computers.footnote37 On that basis, government statistics claim that productivity levels in the computers and electronics sub-sector rose at an average rate of over 10 per cent per year between 1987 and 2011, even as productivity growth rates outside of that sub-sector fell to around 2 per cent per year over the same period.footnote38 Since 2011, trends across the manufacturing sector have worsened: real output per hour in the sector as a whole was lower in 2017 than at its peak in 2010. Productivity growth rates in manufacturing collapsed precisely when they were supposed to be rising rapidly due to industrial automation.

Correcting manufacturing-productivity statistics in the us brings them more into line with trends visible in the statistics of other countries. In Germany and Japan, manufacturing-productivity growth rates have fallen dramatically since their postwar peaks. In Germany, for example, manufacturing productivity grew at an average annual rate of 6.3 per cent per year in the 1950s and 60s, falling to 2.4 per cent since 2000. This downward trend is to some extent an expected result of the end of an era of rapid, catch-up growth. However, it should still be surprising to the automation theorists, since Germany and Japan have raced ahead of the us in the field of industrial robotics. Indeed, the robots used in Tesla’s largely automated car factory in California were made by a German robotics company.footnote39 German and Japanese firms deploy about 60 per cent more industrial robots per 10,000 manufacturing workers, compared to the us.footnote40

Yet deindustrialization continues to take place in all these countries, despite lacklustre manufacturing-productivity growth rates: that is, it is taking place as the automation theorists expect, but not for the reasons they offer. To explore the causes of deindustrialization in more detail, I use the following accounting identity. For any given industry, the rate of growth of output (ΔO) minus the rate of growth of labour productivity (ΔP) equals the rate of growth of employment (ΔE). Thus, ΔO – ΔP = ΔE.footnote41 So, for example, if the output of automobiles grows by 3 per cent per year, and productivity in the automobile industry grows by 2 per cent per year, then employment in that industry must necessarily rise by one per cent per year (3 – 2 = 1). Contrariwise, if output grows by 3 per cent per year and productivity grows by 4 per cent per year, employment will contract by 1 per cent per year (3 – 4 = -1).

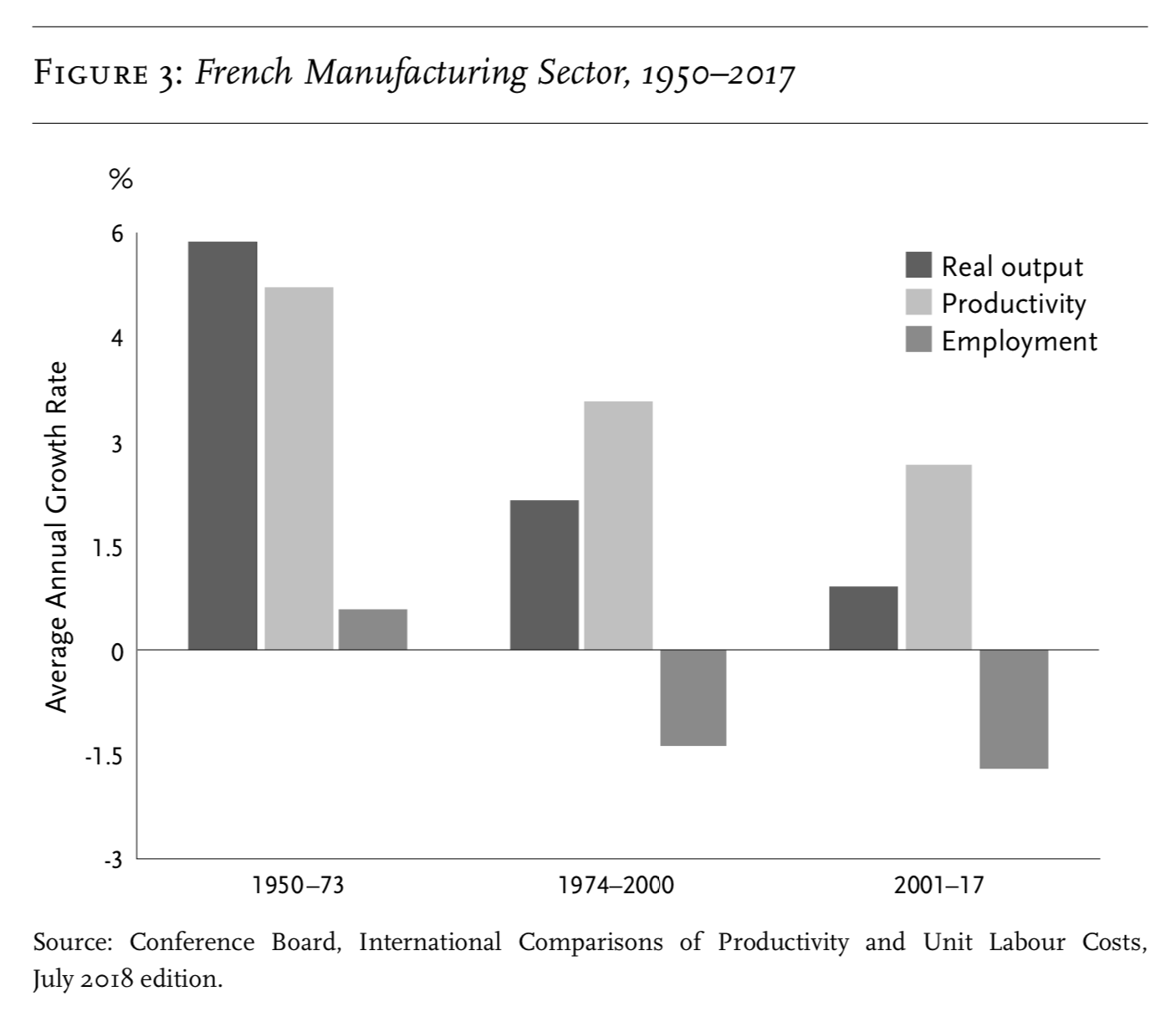

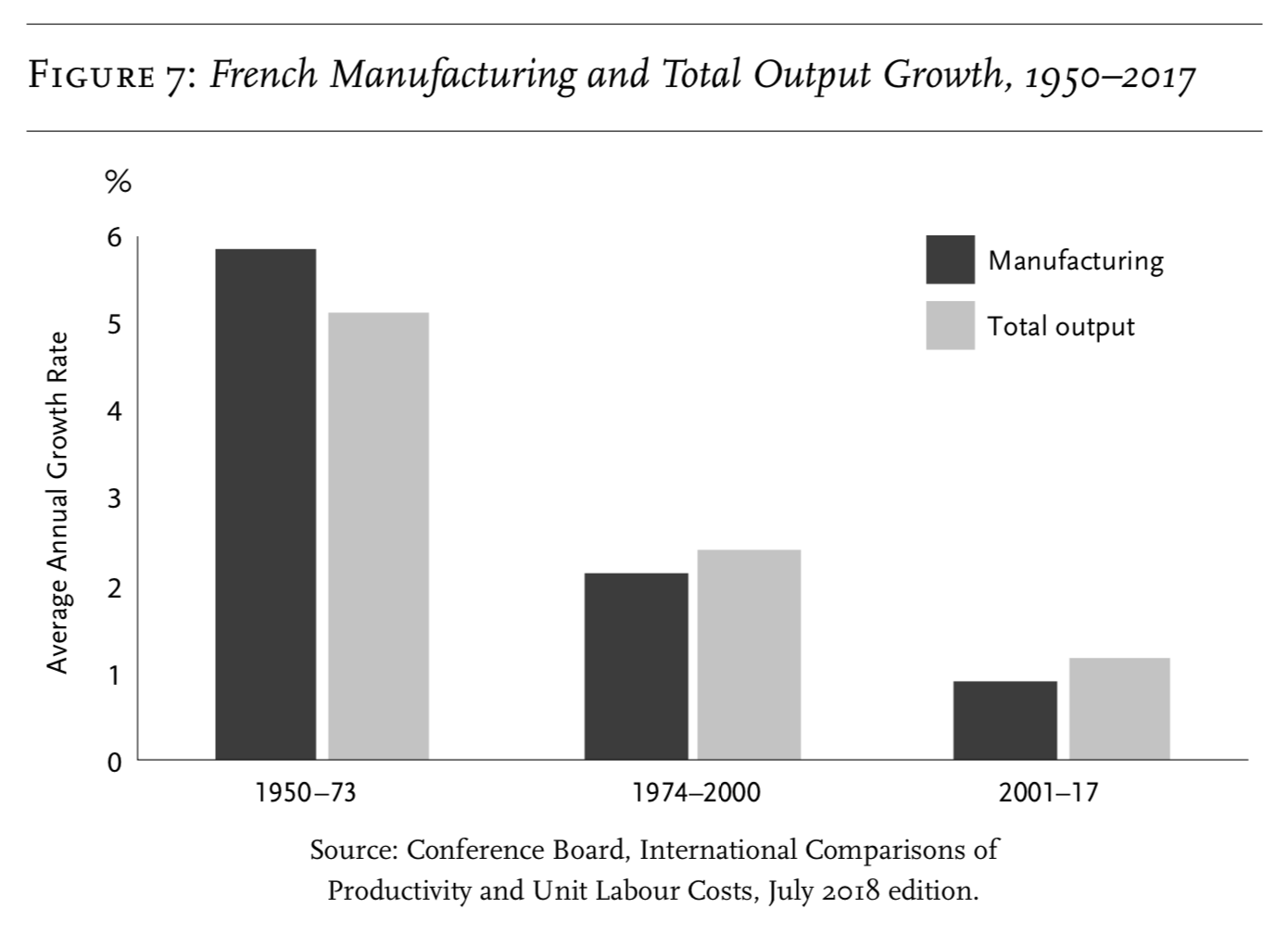

Disaggregating manufacturing-output growth rates in France provides us with a sense of the typical pattern playing out across the high-income countries (Figure 3).footnote42 During the so-called Golden Age of postwar capitalism, productivity growth rates in French manufacturing were much higher than they are today—5.2 per cent per year, on average, between 1950 and 1973—but output growth rates were even higher than that—5.9 per cent per year—as a result of a steady increase in employment of 0.7 per cent per year. Since 1973, both output and productivity rates have declined, but output rates fell much more sharply than productivity rates. By the early years of the 21st century, productivity growth rates—although much slower, at 2.7 per cent per year—were now faster than their corresponding output growth rates—at 0.9 per cent—as manufacturing employment contracted rapidly, by 1.7 per cent per year.

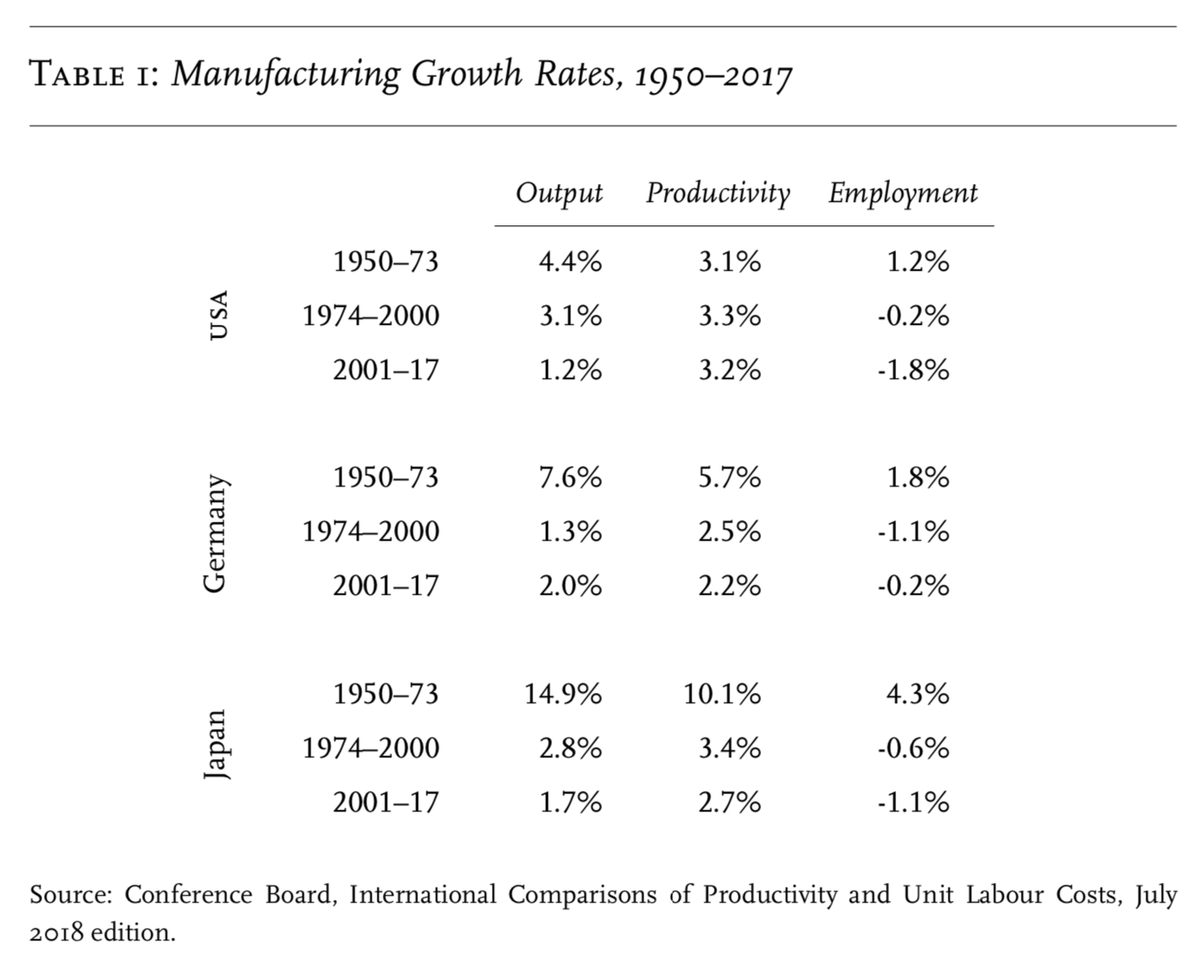

This disaggregation helps explain why automation theorists falsely perceive productivity to be growing at a rapid pace in manufacturing: in fact, productivity growth has been rapid only relative to extremely sluggish output growth. The same pattern can be seen in the statistics of other countries: no absolute decline in levels of manufacturing production has taken place, but there has been a decline in the output growth rate, with the result that output is growing more slowly than productivity (Table 1). The simultaneity of limited technological dynamism and worsening economic stagnation combines to generate a progressive decline in industrial employment levels.

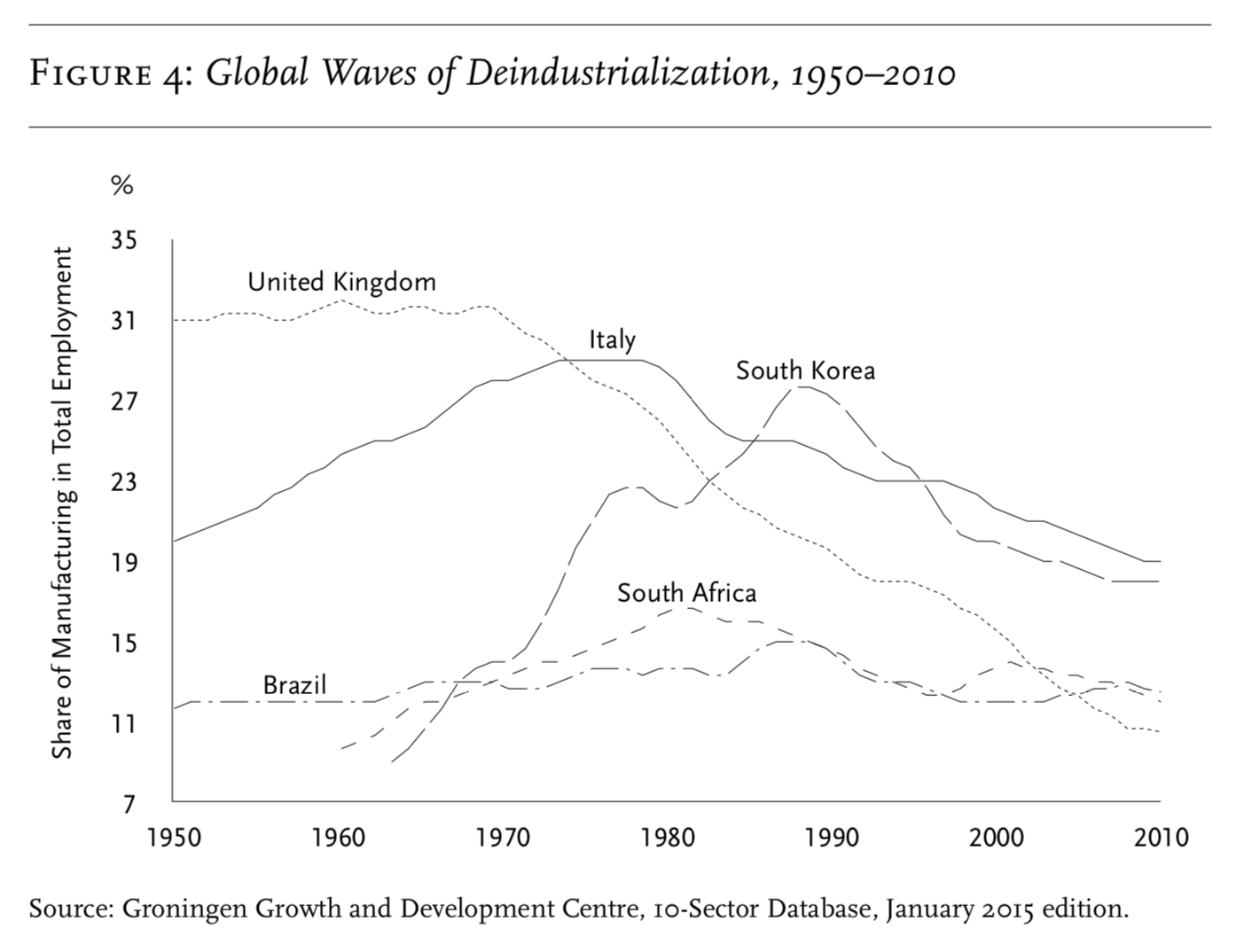

As such, ‘output-led’ deindustrialization is impossible to explain in purely technological terms.footnote43 In searching for alternative perspectives, economists have mostly preferred to describe it as a harmless evolutionary feature of advanced economies. However, that perspective is itself at a loss in explaining extreme variations in the gdp per capita levels at which this supposedly evolutionary economic shift has taken place. Deindustrialization unfolded first in high-income countries in the late 1960s and early 1970s, at the tail-end of a period in which levels of income per person had converged across the us, Europe and Japan. In the decades that followed, deindustrialization then spread ‘prematurely’ to middle- and low-income countries, with larger variations in incomes per capita (Figure 4).footnote44 In the late 1970s, deindustrialization arrived in southern Europe; much of Latin America, parts of East and Southeast Asia, and southern Africa followed in the 1980s and 1990s. Peak industrialization levels in many poorer countries were so low that it may be more accurate to say that they never industrialized in the first place.footnote45

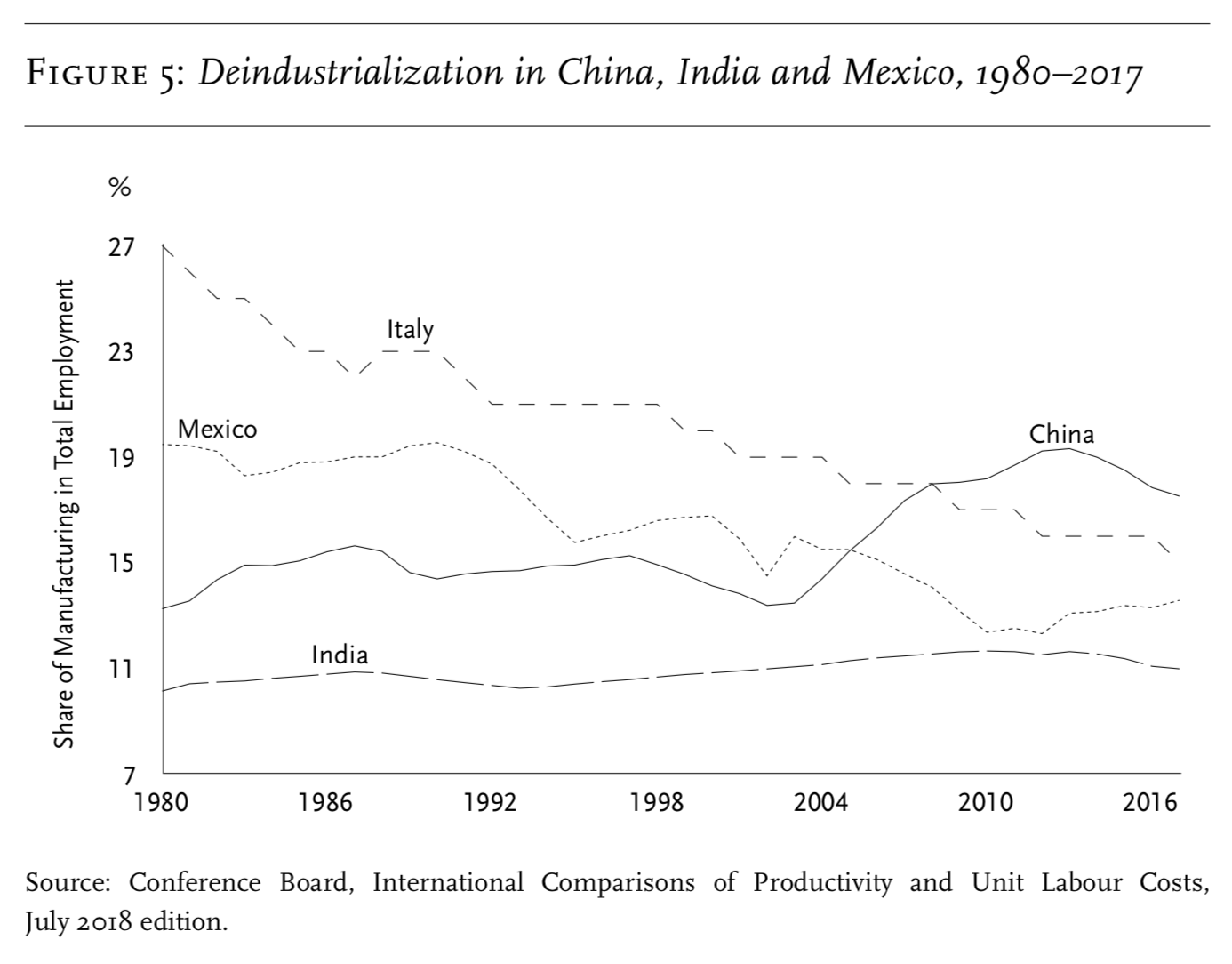

By the end of the 20th century, it was possible to describe deindustrialization as a kind of global epidemic: worldwide manufacturing employment rose in absolute terms by 0.4 per cent per year between 1991 and 2016, but that was much slower than the overall growth of the global labour force, with the result that the manufacturing share of total employment declined by 3 percentage points over the same period.footnote46 China is a key exception, but only a partial one (Figure 5). In the mid 1990s, Chinese state-owned enterprises shed large numbers of workers, sending manufacturing-employment shares on a steady downward trajectory.footnote47 China re-industrialized, starting in the early 2000s, but then began to deindustrialize once again in the mid 2010s: its manufacturing-employment share has since dropped from 19.3 per cent in 2013 to 17.5 per cent in 2017, with further falls likely. If deindustrialization cannot be explained by either automation or the internal evolution of advanced economies, what could be its source?

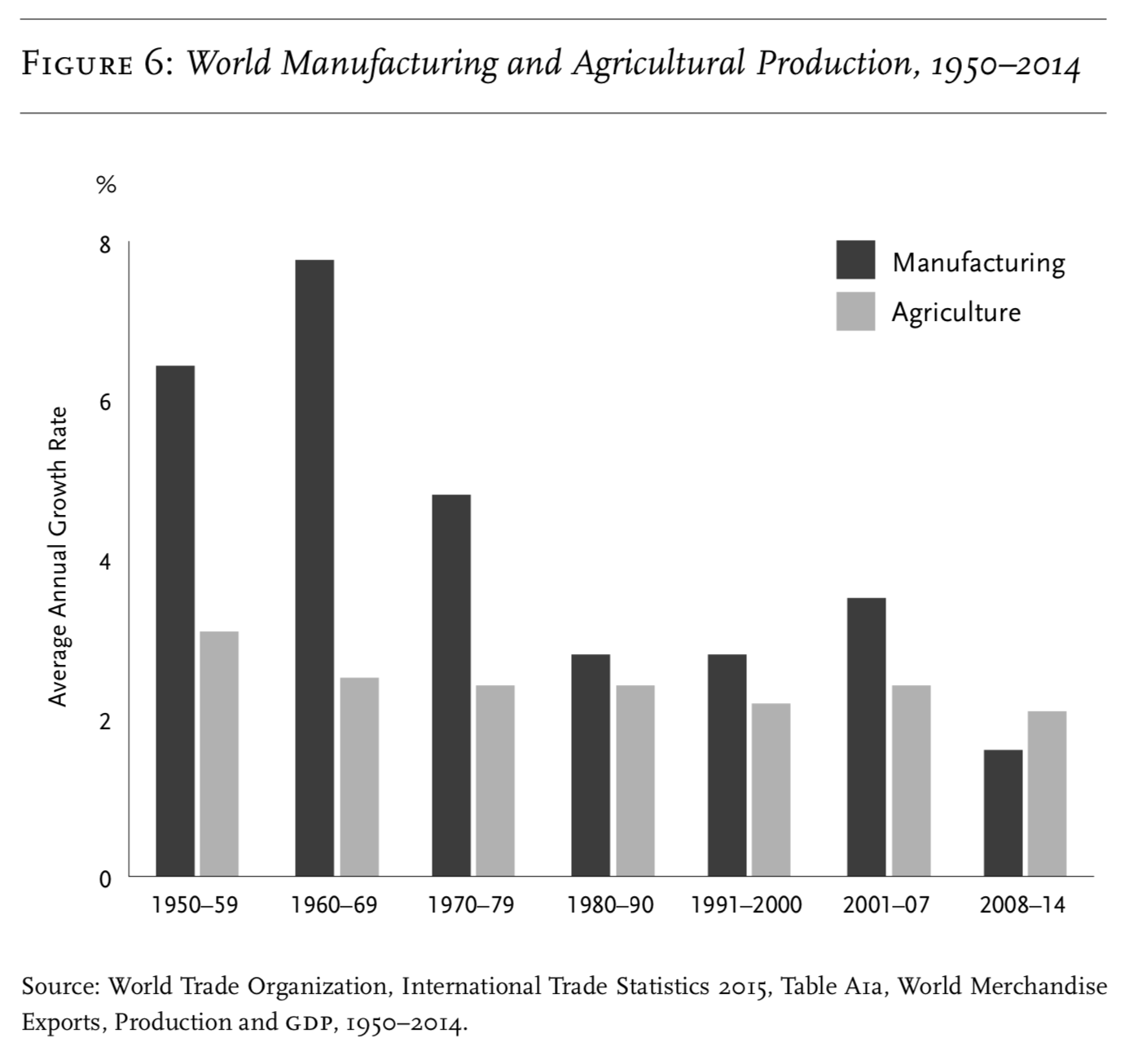

3. blight of manufacturing overcapacity

What the economists’ accounts fail to register in explaining deindustrialization is also what is missing from the automation theorists’ accounts. The truth is that rates of output growth in manufacturing have tended to decline, not only in this or that country, but worldwide (Figure 6).footnote48 In the 1950s and 60s, global manufacturing production expanded at an average annual rate of 7.1 per cent per year, in real terms. That rate fell progressively to 4.8 per cent in the 1970s, and to 3.0 per cent between 1980 and 2007. Since the 2008 crisis and up to 2014, manufacturing output expanded at just 1.6 per cent per year, on a world scale—that is, at less than a quarter of the pace achieved during the so-called postwar Golden Age.footnote49 It is worth noting that these figures include the dramatic expansion of manufacturing productive capacity in China. Again, it is the incredible degree of slowdown or even stagnation in manufacturing-output growth, visible on the world scale, that explains why manufacturing-productivity growth appears to be advancing at a rapid clip, even though it is actually much slower than before. More and more is produced with fewer workers, as the automation theorists claim, but not because technological change is giving rise to high rates of productivity growth. On the contrary, productivity growth in manufacturing appears rapid today only because the yardstick of output growth, against which it is measured, is shrinking.

Seen from this perspective, the global wave of deindustrialization can be said to find its origins not in runaway technical change but rather in worsening overcapacity in world markets for manufactured goods. The rise in overcapacity developed stepwise after World War Two. In the immediate postwar period, the us hosted the most dynamic economy in the world, with the most advanced technologies.footnote50 Under the threat of communist expansion within Europe, as well as in East and Southeast Asia, the us proved willing to share its technological largesse with its former imperial competitors Germany and Japan, as well as other ‘frontline’ countries, in order to bring them all under the us security umbrella.footnote51 In the first few decades of the post-wwii era, these technology transfers were a major boost to economic growth in Europe and Japan, opening up opportunities for export-led expansion. This strategy was also supported by the devaluation of European and Japanese currencies against the dollar.footnote52 However, as Robert Brenner has argued, rising manufacturing capacity across the globe quickly generated overcapacity, issuing in a ‘long downturn’ in manufacturing output growth rates.footnote53

What mattered here was not only the later building out of manufacturing capacity in the global South, but the earlier creation of such capacity in countries like Germany, Italy and Japan, which hosted the first low-cost producers in the postwar era who succeeded in taking shares in global markets for industrial goods, and then invading the previously impenetrable us domestic market. That competition caused rates of industrial-output growth in the us to decline in the late 1960s, issuing in deindustrialization in employment terms. As the us responded to heightened import penetration in the 1970s by breaking up the Bretton Woods order and devaluing the dollar, these same problems spread from the highest wage countries in North America and northern Europe to Japan and the rest of Europe.footnote54 Thereafter, as more and more countries built up manufacturing capacity, adopted export-led growth strategies and entered global markets for manufactured goods, falling rates of manufacturing-output growth and consequent labour deindustrialization also spread to Latin America, the Middle East, Asia and Africa, as well as to the global economy taken as a whole.footnote55

Deindustrialization is not only a matter of technological advance, but also of a global redundancy of technological capacities, creating more crowded markets in which rapid rates of industrial-output expansion become more difficult to achieve.footnote56 The mechanism transmitting this problem across the globe was severely depressed prices in global markets for manufactured goods.footnote57 That led to falling income-per-unit capital ratios, then to falling rates of profit, then to lower rates of investment, and hence lower rates of output growth.footnote58 In this environment, firms have faced heightened competition for market share: as overall growth rates slow, the only way to grow quickly is to steal market shares from other firms. Each firm has to do everything it can to keep up with its competitors.footnote59 Overcapacity explains why, since the early 1970s, productivity-growth rates have fallen less severely than output-growth rates: firms have continued to raise their productivity levels as best they can despite falling rates of output growth (or else have gone under, disappearing from statistical averages). As manufacturing-output growth rates slipped below productivity-growth rates in one country after another, deindustrialization spread worldwide.

Driving globalization

Explaining global waves of deindustrialization in terms of global overcapacity rather than industrial automation allows us to understand a number of features of this phenomenon that otherwise appear paradoxical. For example, rising overcapacity explains why deindustrialization has been accompanied not only by ongoing efforts to develop new labour-saving technologies, but also by the building out of gigantic, labour-using supply chains—usually with a more damaging environmental impact.footnote60 A key turning point in that story came in the 1960s, when low-cost Japanese and German products invaded the us domestic market, sending the us industrial-import penetration ratio soaring from less than 7 per cent in the mid-60s to 16 per cent in the early 1970s.footnote61 From that point forward, it became clear that high levels of labour productivity would no longer serve as a shield against competition from lower-wage countries. The us firms that did best in this context were the ones that responded by globalizing production. Facing competition on prices, us multinational firms built international supply chains, shifting the more labour-intensive components of their production processes abroad and playing suppliers off against one another to achieve the best prices.footnote62 In the mid-60s the first export-processing zones opened in Taiwan and South Korea. Even Silicon Valley, which formerly produced its computer chips locally in the San Jose area, shifted its production to low-wage areas, using lower grades of technology (and also benefitting from laxer laws around pollution and workers’ safety).footnote63 mncs in Germany and Japan adopted similar strategies, which were everywhere supported by new infrastructures of transportation and communication technologies.

The globalization of production allowed the world’s wealthiest economies to retain manufacturing capacity, but it did not reverse the overall trend towards labour deindustrialization. As supply chains were built out across the world, firms in more and more countries were pulled into the swirl of world-market competition. In some countries, this move was accompanied by shifts in the location of new plants: rustbelts oriented towards production for domestic markets went into decline, while sunbelts integrated into global supply networks expanded dramatically. Chattanooga grew at the expense of Detroit, Ciudad Juárez at the expense of Mexico City, Guangdong at the expense of Dongbei.footnote64 Yet given the overall slowdown in rates of world manufacturing-market expansion, this re-orientation towards the world market could only result in lacklustre outcomes: the rise of sunbelts failed to balance out the decline of rustbelts, resulting in global deindustrialization.

At the same time, global manufacturing overcapacity explains why the countries that have succeeded in attaining a high degree of robotization are not those that have seen the worst degree of deindustrialization. In the context of intense global competition, high degrees of robotization have given firms competitive advantages, allowing them to take market share from firms in other countries. Thus Germany, Japan and South Korea have some of the highest levels of robotization; they also have the largest trade surpluses in the world. Workers in European and East Asian firms know that automation helps preserve their jobs.footnote65 China is also a top-four country in terms of trade surpluses, providing its manufacturing sector with a gigantic boost in terms of both output and employment growth. China has advanced on this front not due to high levels of robotization, but rather due to a mix of low wages, moderate to advanced technologies, and strong infrastructural capacities. Yet the result was the same: in spite of system-wide overcapacity and slow growth rates, the prc has industrialized rapidly because Chinese firms have been able to take market share away from other firms—not only in the us, but also in countries like Mexico and Brazil—which lost market share as Chinese firms expanded. It could not have been otherwise, since in an environment where average growth rates are low, firms can only achieve high rates of growth by taking market share from their competitors. Whether China will be able to retain its competitive position as its wage levels rise remains an open question; Chinese firms are now racing to robotize in order to head off this possibility.

4. beyond manufacturing

The evidence I have cited so far to explain job loss in the manufacturing sector through worsening overcapacity may appear to have little purchase on the larger, economy-wide patterns—of stagnant wages, falling labour shares of income, declining labour-force participation rates and jobless recoveries after recessions—that the automation theorists have sought to explain by growing technological dynamism. Automation may therefore still seem a good explanation for the decline in demand for labour across the service sectors of each country’s economy, and so across the world economy as a whole. Yet this broader problem of declining labour demand also turns out to be better explained by the worsening industrial stagnation I have described than by widespread technological dynamism.

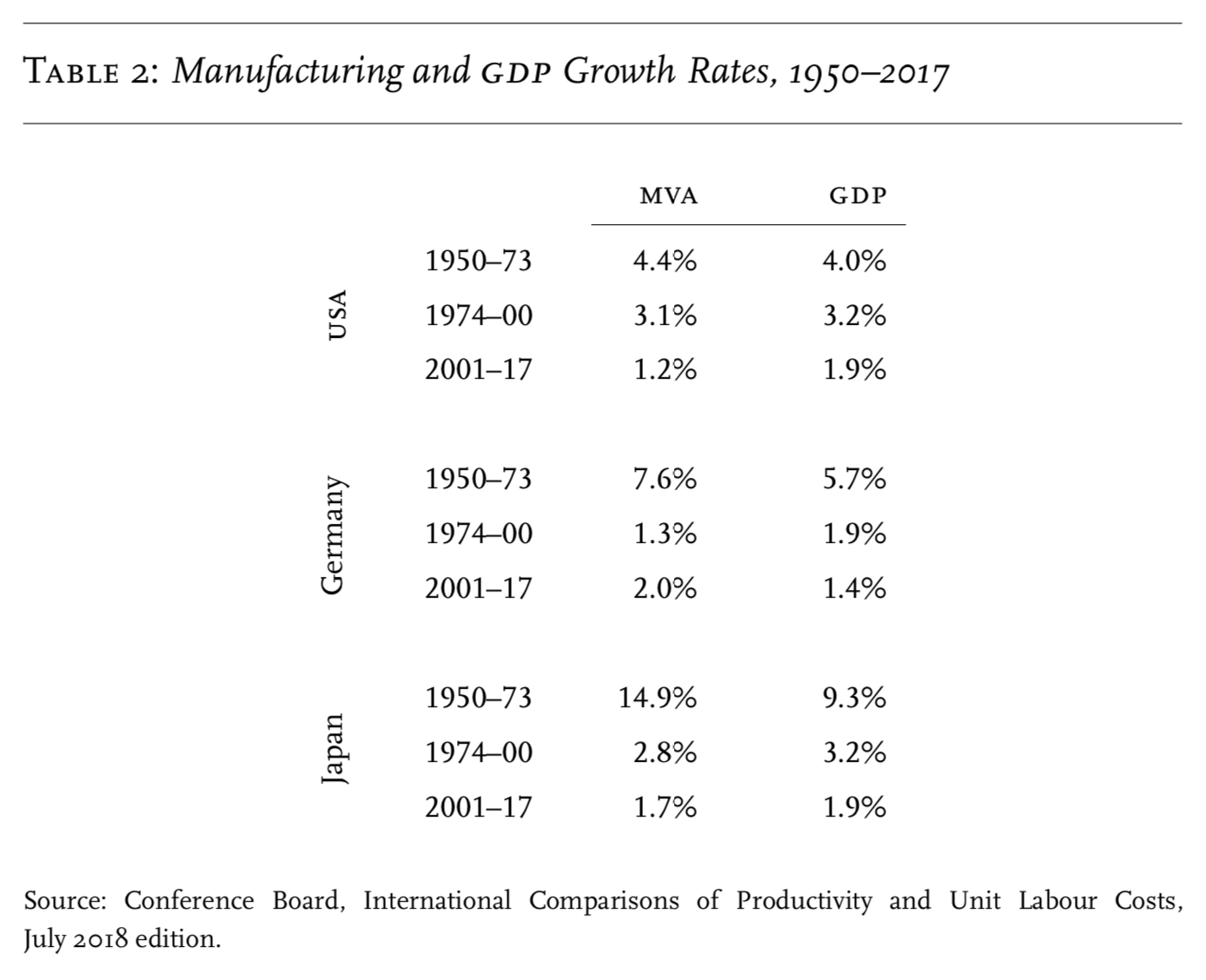

This is because, as rates of manufacturing-output growth stagnated in one country after another from the 1970s onward, no other sector appeared on the scene to replace industry as a major economic-growth engine. Instead, the slowdown in manufacturing-output growth rates was accompanied by a slowdown in overall growth rates. This trend is visible in the economic statistics of high-income countries. France is again a striking example (Figure 7). In France, real manufacturing value added (mva) rose at 5.9 per cent per year between 1950 and 1973, while real value added in the total economy (gdp) rose at 5.1 per cent per year.footnote66 Since 1973, both growth measures have declined significantly: by the 2001–17 period, mva was rising at only 0.9 per cent per year, while gdp was rising at a faster but still sluggish pace of 1.2 per cent per year. Note that during the 1950s and 60s, mva growth generally led the overall economy: manufacturing served as the major engine of overall growth. Since 1973, mva growth rates have trailed overall economic growth. Similar patterns can be seen in other high-income countries (Table 2).Their export-led growth engines sputtered and slowed to a crawl; and as they did so, overall rates of economic growth slowed considerably.footnote67

Economists studying deindustrialization often point out that while manufacturing has declined as a share of nominal gdp, it has maintained, until recently, a more or less steady share of real gdp, which is to say that, between 1973 and 2000, real mva grew at approximately the same pace as real gdp.footnote68 What that has meant in practice is that, as manufacturing has become less dynamic, so has the overall economy. There was no significant shift in demand from industry to services. Instead, as capital accumulation slowed down in manufacturing, the expansion of aggregate output also slowed significantly across the economy as a whole.

This tendency to economy-wide stagnation, associated with the decline in manufacturing dynamism, then explains the system-wide decline in the demand for labour, and so also the problems that the automation theorists cite: stagnant real wages, falling labour shares of income and so on.footnote69 This economy-wide pattern of declining labour demand is not the result of rising productivity-growth rates, associated with automation in the service sector. On the contrary, productivity is growing even more slowly outside of the manufacturing sector than inside of it: in France, for example, while productivity in the manufacturing sector was rising at an average annual rate of 2.7 per cent per year between 2001–17, productivity in the service sector was rising at just 0.6 per cent per year.footnote70 Similar gaps exist in other countries. Once again, the mistake of the automation theorists is to focus on rising productivity growth rather than falling output growth. The environment of slower economic growth explains the low demand for labour all by itself. Workers, and especially workers who are not protected by powerful unions or labour laws, find it difficult to pressure employers to raise their wages when there is so much slack in the labour market.

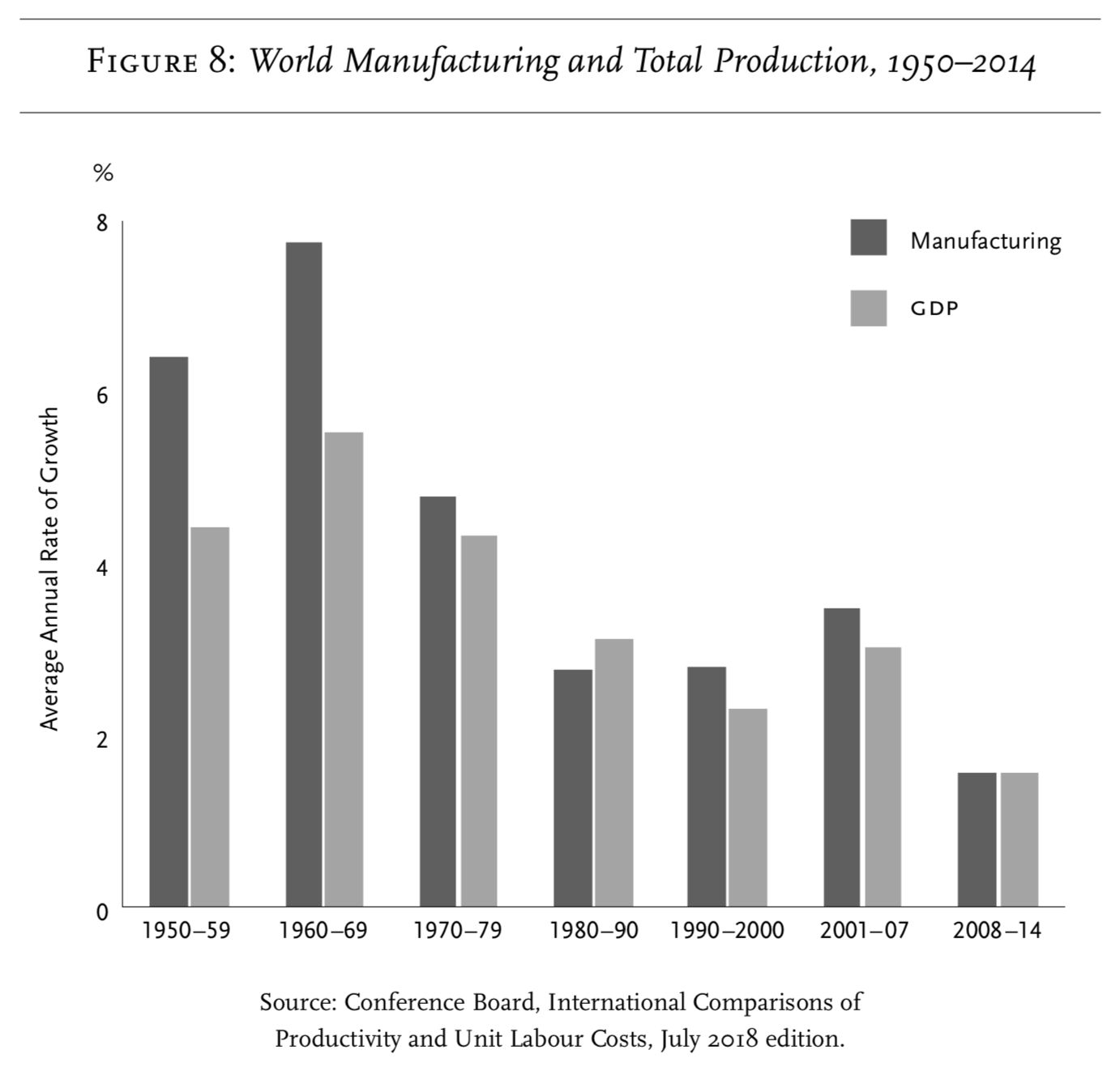

These trends are as visible in the world economy—including China—as they are in the high-income countries (Figure 8). In the 1950s and 60s, global mva growth and gdp growth were expanding at rapid clips of 7.1 per cent and 5.0 per cent respectively, with mva growth leading gdp growth by a significant margin. From the 1970s onward, as global mva growth slowed, so did global gdp growth. In most of the decades that followed, global mva growth continued to lead gdp growth but by a much smaller margin. Since 2008, both rates have been growing at the exceptionally slow pace of 1.6 per cent per year. Again, the implication is that, as manufacturing growth rates declined, nothing emerged to replace industry as a growth engine. Not all regions of the world economy are experiencing this slowdown in the same way or to the same extent, but even countries like China that have grown quickly have to contend with this global slowdown and its consequences. Since the 2008 crisis, China’s economic growth rate has slowed considerably; its economy is deindustrializing.

The clear conclusion is that manufacturing turned out to be a unique engine of overall economic growth.footnote71 Industrial production tends to be amenable to incremental increases in productivity, achieved via technologies that can be repurposed across numerous lines. Industry also benefits from static and dynamic economies of scale. Meanwhile, there is no necessary boundary to industrial expansion: industry consists of all economic activities that are capable of being rendered via an industrial process. The reallocation of workers from low-productivity jobs in agriculture, domestic industry and domestic services to high-productivity jobs in factories raises levels of income per worker and hence overall economic growth rates. The countries that have caught up with the West in terms of income—such as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan—mostly did so by industrializing: they exploited opportunities to produce for the world market, at increasing scale and using advanced technologies, allowing them to grow at speeds that would have been unachievable had they depended on domestic-market demand alone.footnote72

When the growth engine of industrialization sputters—due to the replication of technical capacities, international redundancy and fierce competition for markets—there has been no replacement for it as a source of rapid growth. Instead of workers reallocating from low-productivity jobs to high-productivity ones, the reverse of this process takes place, as workers pool increasingly in low-productivity jobs in the service sector. As countries have deindustrialized, they have also seen a massive build-up of financialized capital, chasing returns to the ownership of relatively liquid assets, rather than investment in new fixed capital.footnote73 In spite of the high degree of overcapacity in industry, there is nowhere more profitable in the real economy for capital to invest itself. Indeed, if there had been, we would have evidence of it in higher rates of investment and hence higher gdp growth rates. This helps explain why firms have reacted to over-accumulation by trying to make their existing manufacturing capacity more flexible and efficient, rather than ceding territory to lower-cost, higher-productivity firms from other countries.footnote74

The lack of an alternative growth engine also explains why governments in poorer countries have encouraged domestic producers to try to break into already oversupplied international markets for manufactures.footnote75 Nothing has replaced those markets as a major source of globally accessible demand. Overcapacity exists in agriculture, too, and is even worse there than in industry; meanwhile services, which are mostly non-tradable, make up only a tiny share of global exports.footnote76 If countries are to retain any dependable link to the international market under these conditions, they must find some way to insert themselves into industrial lines, however oversupplied. System-wide overcapacity and the generalized slowdown in economic growth have therefore been devastating for most poorer countries: the amount of foreign exchange they have captured through liberalization has been pitiful; so, too, has been the number of jobs created.footnote77

Indeed, global economic downshifts have been particularly devastating for low- and middle-income countries, not only because they are poorer, but also because those downshifts have taken place in an era of rapid labour-force expansion: between 1980 and the present, the world’s waged workforce grew by about 75 per cent, adding more than 1.5 billion people to the world’s labour markets.footnote78 These labour market entrants, living mostly in poorer countries, had the misfortune of growing up and looking for work at a time when global industrial overcapacity began to shape patterns of economic growth in post-colonial countries: declining rates of manufactured export growth into the us and Europe in the late 1970s and early 1980s ignited the 1982 debt crisis, followed by imf-led structural adjustment, which pushed countries to deepen their imbrications in global markets at a time of ever slower global growth and rising competition from China. In spite of shocks to the demand for labour generated by slowing global growth rates and rising economic turmoil, huge numbers of workers were still forced to seek employment in order to live.footnote79

Some may respond that the present low rates of global growth are in fact nothing out of the ordinary, if only we shift our baseline from the exceptional postwar ‘Golden Age’ to previous periods, such as the pre-wwi era. But a global perspective on the decline in the demand for labour provides the answer to this objection. It is true that, during the Belle Epoque, average rates of economic growth were more comparable to growth rates today.footnote80 However, in that period, large sections of the population still lived in the countryside and produced much of what they needed to live.footnote81 European empires still overran the globe, not only limiting the diffusion of new manufacturing technologies to a few regions, but also actively deindustrializing the rest of the world economy.footnote82 Yet in spite of the much more limited sphere in which labour markets were active—and in which industrialization took place—the pre-wwi era, as also the inter-war period, was marked by a persistently low demand for labour, making for employment insecurity, rising inequality and tumultuous social movements aimed at transforming economic relations.footnote83 In this respect, the world of today does look like the world of the Belle Epoque.footnote84 The difference is that today, a much larger share of the world’s population depends on finding work in labour markets in order to live.

What automation theorists describe as the result of rising technological dynamism is actually the consequence of worsening economic stagnation: productivity-growth rates appear to rise when, in reality, output-growth rates are falling. This mistake is not without reason. The demand for labour is determined by the gap between productivity and output growth rates. Reading the shrinking of this gap the wrong way around—that is, as due to rising productivity rather than falling output rates—is what generates the upside-down world of the automation discourse. Proponents of this discourse then search for the technological evidence that supports their view of the causes for the declining demand for labour. In making this leap, the automation theorists miss the true story of overcrowded markets and economic slowdown that actually explains the decline in labour demand.

Yet even if automation is not itself the primary cause of a low demand for labour, it is nevertheless the case that, in a slow-growing world economy, technological changes within a near-future horizon may still threaten large numbers of jobs with destruction, in a context of economic stagnation and slower rates of job creation. Technological change then acts as a secondary cause of a low labour demand, operating within the context of the first. The concluding section of this essay in nlr 120 will address these technological dynamics, as well as the socio-political problems—and opportunities—generated by a persistently low demand for labour in late-capitalist societies.