What is the verdict on Cuba’s economy, nearly a quarter of a century after the collapse of the Soviet bloc? The story generally told is a simple one, with a clear message. It describes a cyclical alternation of government policy between moments of pragmatic capitulation to market forces, which account for any progress, and periods of ideological rigidity and re-assertion of state control, which account for all economic difficulties.footnote1 After the dissolution of the Comecon trading bloc, us Cuba watchers were confident that the state-socialist economy faced imminent collapse. ‘Cuba needs shock therapy—a speedy shift to free markets’, they declared. The restoration of capitalism on the island was ‘inevitable’; delay would not only hamper economic performance but would inflict grave human costs and discredit Cuba’s social achievements. Given his stubborn refusal to embark on a course of liberalization and privatization, Fidel Castro’s ‘final hour’ had at last arrived.footnote2

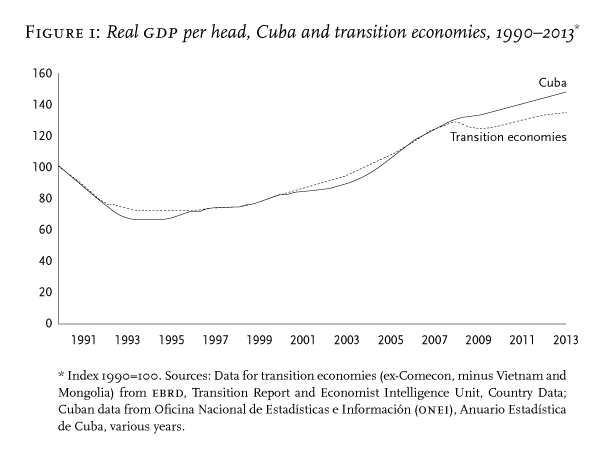

The problem with this account is that reality has conspicuously failed to comply with its predictions. Although Cuba faced exceptionally severe conditions—it suffered the worst exogenous shock of any of the Soviet-bloc members and, thanks to the long-standing us trade embargo, has confronted a uniquely hostile international environment—its economy has performed in line with the other ex-Comecon countries, ranking thirteenth out of the 27 for which the World Bank has full data. As Figure 1 shows, its growth trajectory has followed the general trend for the ‘transition economies’: a deep recession in the early 1990s, followed by a recovery which took around a decade to restore real per capita national income to its 1990 level, rising roughly 40 per cent above it by 2013.footnote3

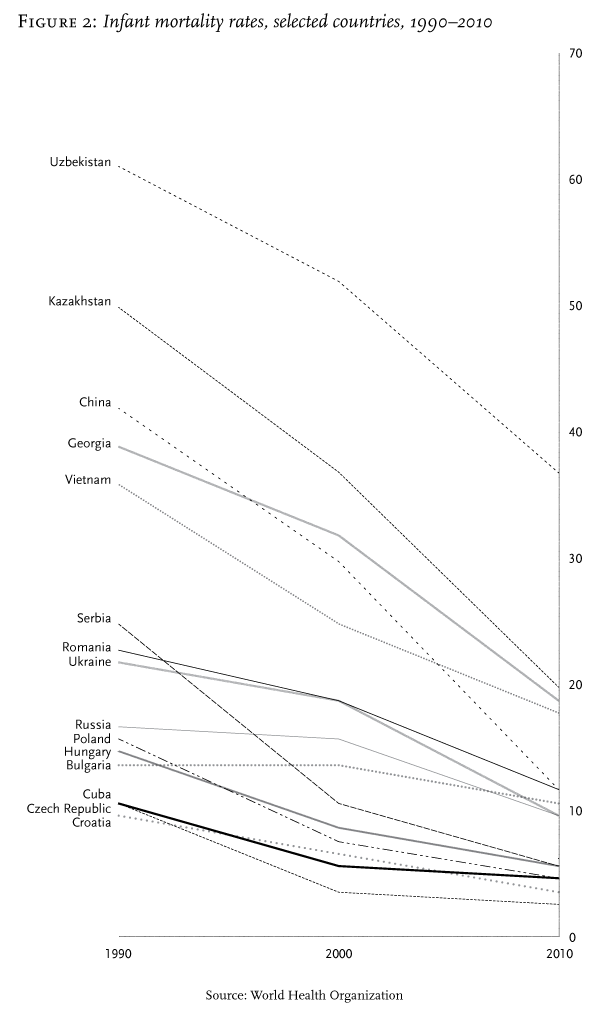

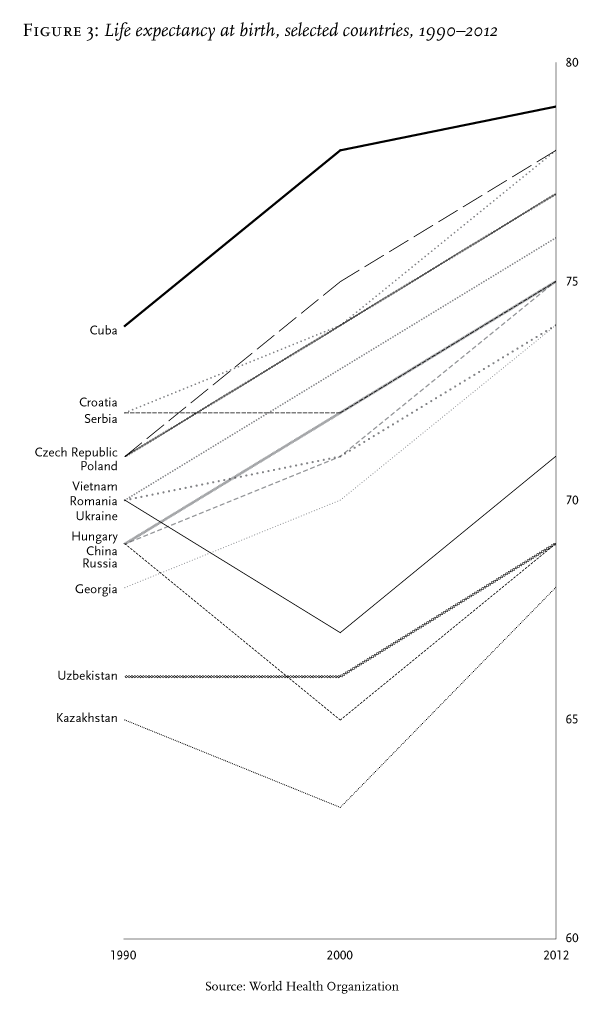

There is no doubt that Cubans have suffered severe hardship since 1990, but in terms of social outcomes, other ex-Comecon countries had it worse. As shown in Figure 2, Cuba’s infant-mortality rate in 1990 was 11 per thousand, already much better than the Comecon norm; by 2000 it was down to just 6 per thousand, a faster improvement than many of the Central European countries that had been taken under the eu’s wing. Today it is 5 per thousand—better than the us, according to the un’s estimate, and far above the Latin American average. Life-expectancy data, shown in Figure 3, give a similar picture: in Cuba, life-expectancy rose from 74 to 78 years in the course of the 1990s, despite a slight rise in mortality rates for vulnerable groups during the most difficult years.footnote4 In the other ex-Comecon countries, rising poverty contributed to an average decline from 69 to 68 years over the 1990s. Today, Cuba has one of the highest life-expectancy rates of the ex-Soviet bloc and among the highest in Latin America.

Miami’s judgement

These outcomes have been largely overlooked by mainstream specialist commentary outside the island, a field that is largely us-based and funded, and overwhelmingly dominated by émigré ‘Cubanologists’, as they have styled themselves, deeply hostile to the Havana regime.footnote5 Leading figures since the 1970s have included Carmelo Mesa-Lago at the University of Pittsburgh, ‘the Dean of Cuba Studies’ and author of over thirty books; and his frequent co-author Jorge Pérez-López, director of international economic affairs for the us Department of Labor, a key nafta negotiator and long-serving head of the Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy. The asce’s annual publication Cuba in Transition, published from Miami, offered a series of blueprints for restructuring the island’s economy along capitalist lines. As their journal’s title suggests, the Cubanologists operated within the assumptions of ‘transition economics’, which emerged as a branch of development economics in the early 1990s to manage the opening of the former Comecon countries to Western capital. This model in turn drew on the Washington Consensus framework which had crystallized around the neoliberal reforms imposed on indebted Latin American countries by the imf and World Bank in the 1980s.footnote6 Its policy prescriptions centred on opening the economy to global capital flows, privatizing state assets, deregulating wages and prices and slashing social spending—the programme implemented across Central and Eastern Europe, as well as much of the former Soviet Union, by technocrats and advisors from the imf, World Bank, ebrd, usaid and other international institutions. Among the first in the field was János Kornai’s avowedly Hayekian The Road to a Free Economy (1990); within a few years a flourishing ‘transition’ industry had developed, which held as axiomatic that there was only one route to be followed—from planned state-socialist economy to free-market capitalism. Resistance was not only futile but costly, for partial reforms were ‘doomed to fail’.footnote7 When the ‘transition countries’ plunged into recession after 1990, their difficulties were blamed on the half-heartedness of their political elites: ‘speed and scale’ were of the essence; it was imperative to take advantage of the ‘extraordinary politics’ of the period.footnote8

By the late 1990s, several factors had led to a modification of the ‘transition’ orthodoxy. First, the stabilization of pro-Western regimes across most of the ex-Soviet bloc lessened the sense of political urgency. Second, the contrast between the severe contraction of the privatized ex-Comecon economies—and disappointing outcomes for Structural Adjustment programmes in Latin America and Africa—and booming state-led development in China and the newly industrializing countries of East Asia was too glaring to ignore. The emerging Post-Washington Consensus (pwc) put more emphasis on institutions and ‘good governance’. Transition economists lagged behind their development colleagues in making this shift, but by the turn of the millennium an influential textbook acknowledged the ‘humbling’ divergence between their predictions and actual outcomes; transition studies went on to develop its own pwc.footnote9 But if there was now less emphasis on the speed of reform, ‘progress in transition’ was still considered the main explanation for economic success and problems were routinely attributed to insufficient liberalization.

Mainstream Cubanology has largely adhered to the Washington Consensus model. It has held the ‘anti-market features’ of Cuban policy responsible for the deep recession of 1990–93 and the privations of the período especial; exogenous factors were given secondary significance. In line with the critique of partial reforms, Mesa-Lago attacked Cuba’s 1994 measures as ‘half-hearted’ and ‘half-baked’.footnote10 The usual explanation for Cuban policy is very simple: it is the result of the President’s ‘stubborn dogmatism’, his ‘aversion to market reform, his willingness to smash those who oppose him and to take the whole nation with him in his opposition’. A few commentators spread the blame a little more broadly: Rubén Berrios castigates an ageing leadership and rigid bureaucrats, clinging to old habits; Mauricio de Miranda Parrondo sees a resistance to reform on the part of the ruling layer as a whole.footnote11 Failure to pursue ‘transition’ policies has left the Cuban economy bankrupt or, more recently, rendered it a mere dependency of Venezuela.

View from Havana

The Pittsburgh–Miami axis tends to overlook two important respects in which Cubans’ experience has differed from those of the ex-Comecon populations in Central Europe. First, memories of the extreme poverty and deprivation associated with the pre-communist system, together with the relative strength of Cuba’s achievements in health and education before 1989, have left them with less appetite for radical free-market reform. Second, while nationalist sentiment in Central Europe could embrace ‘transition’ as liberation from Russian domination, in Cuba it is popularly perceived as a threat to national sovereignty emanating from the historical predator, the us. This is the outlook within which Cuban economists and policy-makers are working.footnote12 Advisors and officials do not talk in terms of ‘transition’ but rather of ‘adjustment’—responding to a radical change in external conditions, within parameters set by nationalist and socialist ideology. This implies a more flexible policy framework than the rigid, ideologically driven rejection of reform depicted by the Cubanologists. Economists and policy-makers alike expressed these parameters in terms of principios, rather than Marxist-Leninist dogma or a ‘party line’. These principles invariably included upholding national sovereignty, preserving los logros de la revolución—the gains or achievements in health, education, social equality and full employment; often referred to simply as los logros—and maintaining ‘revolutionary ethics’, which has involved a strong official stand against corruption and disapproval of ostentatious display.footnote13 These principles impose distinct constraints on policy choices.

Internal debates about economic policy have been largely invisible to foreign observers, including the us-based Cubanologists. In part this is due to Cuba’s closed political process and state control of the media, leaving many external commentators dependent on rumours; much of what reaches the us derives from selective reports by dissident groups, funded either by émigré organizations or us programmes, and serves primarily to confirm consensus preconceptions. The complex processes of discussion, policymaking and adaptation, in which leaders’ preferences do not always prevail, have been closed to outsiders. As well as the constant rounds of meetings at neighbourhood, regional and national levels structured by the Poder Popular system, there have been ongoing debates among economists that feed into policy discussions.

Researchers from the Centro de Estudios de la Economía Cubana (ceec), the Centro de Investigaciones sobre la Economía Internacional (ciei), the Centro de Investigaciones de la Economía Mundial (ciem), the Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Económicas (inie) at the Ministry of the Economy and Planning—and, until 1996, the Centro de Estudias de las Americas (cea)—have participated in regular seminars with policymakers, identifying the weaknesses of the existing system and debating remedies for them. Working groups established by a University of Havana research programme examined different models of socialism and their application to Cuba; problems at the sectoral economic level; proposals for reforming enterprise management; and the implications, both political and philosophical, of the end of the Soviet bloc. Their writings—published in the ciem’s Economía Cubana: Boletín Informativo, the inie’s Cuba: Investigación Económica and elsewhere—tend to adhere to official styles of discourse, which can obscure their significance for outside observers; important analytical insights can be buried among ponderous historical considerations, quotes from leaders’ speeches and praise for achievements thus far. The vocabulary is also unfamiliar: instead of imf jargon, Cuban economists refer to ‘adaptation’, ‘updating’, the ‘use of market mechanisms’, the ‘adjustment’ of administered prices, ‘decentralizing’ measures and ‘emergent’ economic processes. Read through the transition-or-bust spectacles of the Cubanologists, this amounts to no debate at all, and confirms their suspicion that policy is entirely determined by presidential whim.footnote14

There is, of course, a range of external commentary on the island that falls outside the mainstream; here one can distinguish three approaches. First, regime sympathizers or apologists, who counter the negative bias of Cubanology by putting a strongly positive gloss on Cuban realities. In common with the consensus, they present the choice as being between defiance or transition to capitalism, but celebrate the former and lament any market opening as ‘surrendering to the inevitable’.footnote15 A second group could be described as critical friends: they are more positive about Cuban policymakers’ objectives, and more willing to acknowledge the problems the country faces; but like the Cubanologists, they link ‘transition’ progress to economic performance and argue that insufficient ‘systemic change’ is to blame for Cuba’s woes.footnote16 Finally, a small number of economists have attempted to analyse Cuba’s development on its own terms, without teleological assumptions, in a comparative perspective. On the basis of these investigations, José March-Poquet has suggested that Cuban economic policy may offer an alternative to that of the ‘transition’ countries, one that is evolutionary and experimental in nature; Claes Brundenius, comparing its strengths and weaknesses with those of Vietnam and China, as well as the Central and Eastern European countries, tentatively concludes that it may produce ‘a market economy with Cuban characteristics’.footnote17

Given the implicit comparison in mainstream commentaries between Cuba’s course and those of the ‘transition’ economies, it is notable that genuinely comparative studies of them are relatively rare. In part this may arise from the problem of identifying commensurate data sets, but it also reflects a general tendency among Cubanologists to focus exclusively on their native island.footnote18 At the same time, mainstream ‘transition’ economists, who do make extensive use of comparative frameworks—one of their strengths—tend to concentrate on Central and Eastern Europe, the former ussr, or Russia–China contrasts, ignoring the light that might be shed on them by Cuba’s distinctive course. What follows, then, will be an analytical narrative, tracing the evolution of Cuba’s adjustment policy—from initial crisis management to stabilization, restructuring and the most recent round of reforms, under Raúl Castro—within a comparative perspective.footnote19 It aims not only to highlight the problems of existing interpretations but to contribute to a more fruitful discussion of Cuba’s path and, more generally, to re-open the question of alternative development strategies for small countries in a globalized world.

1. Managing Crisis

Of all the Soviet-bloc countries, Cuba was particularly vulnerable to the collapse of the ussr. It had been virtually compelled to enter relations with Comecon, which it joined in 1970, by the us embargo, imposed by Kennedy in 1962 after the failure of the cia-backed military invasion the year before, which cut off relations with its historic trading partner. During the 70s and 80s, Cuba had grown increasingly dependent on the ussr for trade and finance. The economy had become heavily reliant on sugar exports, for which Cuba received a preferential price—$0.42 per pound at the start of the 90s, compared to a world-market price of $0.09. Imports amounted to 40 per cent of gdp and included 50 per cent of the island’s food supply, 90 per cent of its oil and essential inputs for agriculture and manufacturing; a $3bn trade deficit was financed by the Soviet Union on generous terms. After attempts to convert Comecon agreements to hard-currency trading in January 1990, bilateral arrangements with the ussr broke down altogether in 1991.footnote20 Food, fuel and inputs ceased to arrive. The scale of this exogenous shock is evident from the comparative data on export earnings, external credit and import capacity.

In Cuba’s case, export earnings were hit particularly hard, dependent as they were on the sugar price premium and with exceptionally sparse opportunities for diversification to other trading partners. In most of the ex-Comecon countries, export earnings had almost regained their 1990 level by 1993; in Cuba’s case, they were 79 per cent lower—down from $5.4bn to $1.2bn. Havana was also worse hit in terms of external financing. The severity of the shock was compounded by the sudden loss of external credit and lack of new sources of finance. While ‘transition’ countries enjoyed the support of the imf, World Bank and ebrd to help with their post-Comecon adjustment, us sanctions meant there was no such assistance for Cuba. Total net official loans to ‘transition’ economies for 1991–96 amounted to $112 per capita, while for Cuba the figure was $26.footnote21 With the us Office of Foreign Assets Control (ofac) threatening third-country financial institutions with prosecution for dealings with Havana, Cuba’s access to commercial credit during the crisis was also extremely limited.

The result of collapsing export earnings and external credit was an acute contraction of Cuban import capacity, unmatched by any other post-Comecon country. Between 1990 and 1993, a 70 per cent decline in import spending slashed Cuba’s imports/gdp ratio from around 40 per cent, one of the highest of the group, to 15 per cent, one of the lowest, according to the ebrd. By 1993, Cuba had less money available to cover its total import needs than it had spent in 1990 on fuel and food alone. At the same time, Cuba’s attempts to rebuild foreign-exchange earnings were obstructed by us sanctions, which blocked access not only to us markets but also to loans or development aid from most multilateral institutions, while making commercial finance expensive and difficult to secure. As a result, Cuba faced the harshest foreign-exchange constraints of any former Comecon country; this restricted investment and growth, and left the economy exceptionally vulnerable to changes in terms of trade or fluctuations in harvests.

Emergency measures

Cubanologists’ claims that endogenous features were responsible for the severity of the 1990–93 contraction ignore the extraordinarily severe impact of the collapse of Comecon. Seeing only a choice between transition or rigidity, they have characterized government policy after 1990 as merely an extension of its ‘anti-market’ 1986 rectificación strategy—a series of measures adopted to address the 1980s slowdown facing all Comecon countries, including an anti-corruption drive, curbs on agricultural markets, investment in tourism and joint ventures. Havana was accused of failing to ‘take steps to address the profound economic crisis’.footnote22 But in the face of the external shock of 1990–91, the Cuban government did not do nothing. Emergency measures were swiftly adopted to direct rapidly diminishing resources to economic and social priorities. Indeed, the severity of the shock made continuity impossible: with inputs failing to arrive, the economic plan quickly ceased to function. Rather than embark on a process of liberalization and privatization like its former Comecon partners, however, the Cuban approach preserved, and built on, its existing institutional assets. These included not only the welfare state, price controls, monopoly of international exchange and national ownership of the means of production, but also a capacity for a state-led, collective response that benefited from a long-standing tradition of galvanizing voluntary support through mass mobilizations and a policy process that could draw on mechanisms for public participation and debate.

Fidel Castro’s characterization of the crisis years as a período especial en tiempo de paz—‘special period in time of peace’—was seen by outside observers as a euphemism, but within Cuba it was immediately understood as a reference to established civil-defence procedures, in case of natural disaster or us attack. The Economic Defence Exercise of 1990—in which electricity and water supplies were cut off for short periods, to rehearse emergency collective responses involving factories, offices, households, schools and hospitals—used methods of collective organization and multi-agency coordination similar to those of hurricane-preparedness or military-defence exercises. The same types of mobilization were evident in the early 1991 Food Programme, in which farmers and city dwellers were called upon to contribute to food production; the December 1991 Spare Parts Forum, on ideas for recycling machinery and substituting for imports; and the January 1992 Energy Plan, in which households, enterprises and local authorities identified ways to cut fuel consumption.

Cuba’s efforts to maintain employment and welfare provision during the crisis, and to ensure that basic needs were met, were again in strong contrast to the ‘transition’ countries, where official unemployment had soared to an average 20 per cent by the early 1990s.footnote23 In Cuba, where 98 per cent of the official workforce was employed by the state, the total number of jobs actually rose by 40,000 between 1990–93 and the official unemployment rate fell from 5.4 to 4.3 per centfootnote24—even as the economy contracted by a third, investment projects were abandoned, fuel allocations cut, public transport reduced, the working week shortened (from 5.5 to 5 days), and factories either closed or operated on severely reduced hours. A Ministry of Labour and Social Security decree of April 1991 formally assured job security, stipulating that workers laid off due to the lack of inputs would remain on the payroll, receiving two-thirds of their salaries until they were redeployed. The state’s responsibility for guaranteeing basic needs meant that the additional cost of keeping workers employed in this way, rather than on unemployment benefits, was relatively low.

Basic food security was maintained under conditions of acute scarcity during the early 1990s. The acopio, the state distribution body, procured food from both import warehouses and Cuban farms and channelled supplies through the food-rationing system and other networks, such as the vías sociales, which provided free or subsidized meals at workplaces, schools and health centres. Thanks to the ration-system’s fixed prices, the per capita cost of meeting basic food needs, around 40 pesos a month, was kept below the minimum social-security allowance of 85 pesos a month.footnote25 At the outset of the crisis, state-run shops that had sold food beyond the ration—por la libre—at prices closer to market levels were closed down.footnote26 The Food Programme encouraged local self-provisioning and small-scale experimentation, including the use of animal traction, organic fertilizers, biological control of pests and the cultivation of marginal land.footnote27

Decentralization and debate

The Cubanologists’ narrative of policy rigidity and tightly centralized control bears little relation to the ways in which the Cuban state adapted as circumstances altered, even during the worst of the emergency. Decentralization of decision-making to the local level began within the extensive welfare state as food supplies for the ration system and other vías sociales became less reliable.footnote28 Social protection came to depend on a range of local state agencies, including the Sistema de Vigilancia Alimentaria y Nutricional (sisvan)—which monitored nutrition levels, allocated supplementary rations and maintained support networks for mothers and babies, with backing from unicef—and health professionals, who were familiar with the most vulnerable people in their communities. As part of this process the Consejos Populares network, created in 1991, helped in the identification of ‘at risk’ households and the administration of relief programmes.footnote29 This adaptation and decentralization of welfare agencies was accompanied by a relaxation of central control in the economy more generally. As supplies failed to arrive, enterprise managers had to find local solutions to problems; meanwhile the Ministry of Foreign Trade, which formerly had a near monopoly, ceded the right to source inputs and secure markets to hundreds of enterprises.footnote30

A discourse that dismisses Cuba as the only ‘non-democracy’ in the Americas has no room for examination of the array of mass organizations that constitute its effort to create a ‘participatory’ system; but the story of the post-1990 period cannot be understood without reference to these processes. National debates have been launched at critical moments, involving assemblies throughout the island, open to everyone—another contrast with the eastern Comecon countries. In 1990, when the crisis was still unfolding, preparations were already underway for the October 1991 Fourth Congress of the Partido Comunista de Cuba. As the economic problems deepened, the scope and extent of pre-Congress discussions broadened; thousands of meetings were held not only in pcc branches, but also in workplace assemblies and mass organizations.

The Congress, held just three months after the final dissolution of Comecon, produced an 18-point Resolution on the economy that constituted the first comprehensive formal statement of Cuba’s new policy framework.footnote31 Unlike the transition programmes drawn up for the other former Comecon countries with help from Western advisers, the pcc resolution was not a blueprint for liberalization, but a list of broad principles and objectives; no specific measures were announced, nor any timetable or sequencing. But Cubanologists’ characterization of the pcc text as merely ‘anti-market’ is misleading. The resolution reiterated a commitment to the core principles of sovereignty and social protection, and retained an overall framework of state ownership; but beyond that, it included a mixture of liberalizing and state-led approaches. Some items—‘develop tourism’, ‘promote exports’, ‘minimize imports’, ‘seek new forms of foreign investment’, ‘control state spending and money supply’—suggested partial liberalization in response to new international conditions, while others—‘continue the food programme’, ‘give priority to health, education and scientific work’, ‘centralize planning for public benefit’, ‘protect the revolution’s achievements’—indicated the state’s still extensive role. A constitutional reform the following year confirmed the set of social, political and economic priorities while continuing the vagueness about details of policy. Both documents reveal a heterodox and flexible approach to economic policy, through a complex policy-making process that—although it was carefully documented by at least one us researcher at the time—was largely ignored in outside commentary on the island.footnote32

2. Imbalances and Stabilization

Both the strengths and weaknesses of Cuba’s initial policy response to the crisis are evident in the fiscal accounts. In contrast to the sharp contraction of government spending in the transition countries,footnote33 in Cuba overall spending was allowed to rise slightly—from 14.2bn pesos in 1990 to an average of 14.5bn pesos for 1991–93. The government’s priorities were revealed in increased spending on health (up 19 per cent) and subsidies (up 80 per cent), which paid for a 40 per cent rise in medical staff and maintained subsidized food distribution. These increases were only partially offset by sharp cuts in defence, down by 43 per cent between 1989 and 1993, and investment, which fell by more than half. With both gdp and government revenue declining, the fiscal deficit swelled from 10 per cent of gdp in 1990 to 34 per cent by 1993. Macroeconomic balance was clearly not a priority during the initial emergency. The benefits of deficit spending during the crisis were clear—it served to both mitigate the contraction and minimize the welfare cost of the external shock. However, the policy stored up problems for the longer term: in the absence of external finance or any domestic financial market, the deficit was fully monetized, resulting in a sharp decline in the value of money: the black-market rate shrank from around 7 pesos to the dollar in 1990 to over 100 pesos to the dollar in 1993.

This degree of currency depreciation was not exceptional among former Comecon countries, but in Cuba’s case, because inflation was suppressed by state controls, it produced a unique pattern of changes in relative prices and incomes. In the other ex-Comecon countries the liberalization of wages, prices and exchange rates unleashed depreciation–inflation–decapitalization spirals which resulted in sharp declines in real wages, particularly for the lowest paid, so that real-wage inequality widened rapidly.footnote34 In Cuba, the fall in the value of the peso was restricted to prices and exchange rates in the informal economy; within the formal, state-dominated economy, real-wage inequality actually narrowed, because those at the highest end of the scale who could afford imported and black-market goods faced sharply rising prices, while for those on the lowest wages or state benefits, who could only afford the basic fixed-price goods, the cost of living initially remained relative stable.

However, the peso’s decline created a growing gulf between those with access to hard currency and those dependent on peso earnings. People working in the state sector became increasingly aware of the gap between their real incomes and those of people operating in the informal black-market economy, so that material incentives pulled in the opposite direction to moral ones. The collapsing value of the peso relative to the dollar was also a symbol of the erosion of Cuban national self-esteem, with those dependent on peso salaries becoming steadily impoverished relative not only to outsiders—the gusanos who had emigrated to the us and the new influx of tourists—but also to the thieves and jineteros at home. There was also a widening chasm between the heroic official rhetoric of unity and shared hardship, and the everyday reality of poverty and inequality—del dicho al hecho hay un gran trecho, as the saying went. Most corrosive of the discourse of revolutionary ethics was the fact that many of those who had initially refused to engage in black-market activity, or even to buy from the informal markets, now found themselves obliged to do so. Their reluctant participation, reflected in apologetic vocabulary, marked an involuntary acceptance that the need to resolver or sobrevivir had to override other considerations.footnote35 Over time, this dual system undermined work incentives and social solidarity; it increased pressures for pilfering, absenteeism and corruption that were a drain on the formal economy.

By 1993–94 there were urgent social, economic and political imperatives for action to restore monetary stability: food supplies were at their most precarious; desperation would lead to the ‘rafters’ crisis’ and a riot in the capital, the habanazo. Unlike the other ex-Comecon countries, however, but in line with the goal of trying to safeguard los logros, the government refused to adopt a shock-therapy stabilization package. Cubanologists blamed the peso’s fall on this ‘stubbornness’, and accused the government of refusing to acknowledge the problems. But although official Cuban discourse continued to refer to the decline in spending power not as inflation, which would suggest a permanent loss of purchasing power, but as ‘shortages’, the government was not in denial. With the hardships, which were acute by 1993, being shared by all officials apart from the small minority receiving remittances, it was barely necessary to spell out the problems, and economic advisers were busy grappling with the policy challenges.footnote36 A series of reforms were introduced in 1993–94; since they were very different from the Washington Consensus prescriptions for stabilization, they were dismissed as inadequate by the Cubanologists. However, they succeeded in producing a remarkable turnaround.

Return of the dollar

The new measures were not presented as stabilizing reforms, nor primarily intended to tackle currency depreciation. They sought to bring black-market activities into the formal sector, and thus both to lift economic activity and to narrow the fiscal deficit through increased revenues. The first measure, in July 1993, was the removal of the prohibition on holding us dollars. Dollars could henceforth be exchanged for Cuban pesos (cup) and vice versa, for personal transactions. Until then, the Cuban peso had been the only currency circulating within the official economy, apart from a small number of state-owned shops known as diplotiendas which catered mainly to diplomats, foreign students and the few Cubans, mainly musicians and sportspeople, who had earned money abroad.

But now a growing number of Cubans were either receiving family remittances in dollars or obtaining hard currency informally or illegally through the tourist trade. They were supposed to exchange them at the official rate of 1 peso to the dollar; but with the peso’s value having shrunk so far, most people were either using them to shop in the diplotiendas through intermediaries, or exchanging them on the black market. With the widening monetary imbalance, the prohibition on the use of dollars was becoming unworkable: it was wasting police time, stimulating petty corruption and creating frustration among the growing number of Cubans who had to break the law in order to spend their hard currency. Through legalization, and with currency exchange subsequently facilitated by the creation of a convertible peso (cuc, valued at par with the dollar) and establishment of state-run Casas de Cambio (known as Cadecas) in 1995, the government encouraged remittances as a new source of desperately needed foreign exchange. The move also boosted fiscal revenue, through sales taxes in dollar shops, and mitigated the erosion of the state’s authority caused by its increasingly futile efforts to prevent Cubans from using their us dollars.

The reform fell far short of the liberalization of currency markets implemented under Western tutelage in the other ex-Comecon countries as it applied only to personal transactions within the domestic economy; all other foreign-exchange operations remained under the control of the state. But limited as it was in scope and function, it had the effect of incorporating the dual-currency system into the formal economy: the dichotomy was no longer between the black market and the legal sector, but between the personal-transaction sector—where us dollars circulated and could be exchanged at the Cadecas at the ‘unofficial’ market rate, then around 100 pesos to the dollar—and the state sector, which used the ‘official’ exchange rate of dollar/peso parity.

By bringing the dichotomy of the dual-currency system into the open, the Cadecas also changed the way in which Cubans understood the decline in real incomes, for the diminution of the peso could no longer be denied. Lack of purchasing power was now officially quantifiable as a question of poverty rather than of shortages, and the gulf between the minority with access to hard currency and those without became a problem of inequality rather than of illegality. At the same time, the task of restoring real incomes and living standards came to be seen in a different light: adjustment now involved a need to restore the market value of the Cuban peso, which meant that the monetary imbalance had to be brought under control by cutting the fiscal deficit; and the supply of goods, especially foods, available for purchase in pesos had to be increased.

The second measure, introduced in September 1993, extended the scope for self-employment under Decree Law 141. The range of cuentapropista activities expanded from 41 to 158, resulting in an increase in those registered as self-employed from around 15,000 at the end of 1992 to over 150,000 by 1999. This was welcomed by Cubanologists as a liberalizing measure, but criticized for its limited scope. The self-employed were still only around 5 per cent of the workforce; licences lasted only two years and had to be obtained from the local office of the Ministry of Labour; the range of approved activities was mainly limited to personal services. Yet the reform broke new ground by establishing a taxation system for these businesses, with an initially crude—and often regressive—structure of flat rates which was subsequently improved as the capacity for reporting and collection grew.

Consultation

While dollar depenalization and the opening of self-employment were introduced by decree, the regime proceeded more cautiously on the matter of fiscal adjustment, the need for which was recognized at the National Assembly in December 1993. Rather than imposing an austerity package of spending cuts, the government once again launched a national debate and established a new consultation process, the Parlamentos Obreros, to debate the changes. These forums convened over the next few months to consider the proposals for cutbacks; the final package was not introduced until their deliberations were complete, in May 1994. The delay was incomprehensible to Cuba’s would-be external economic advisers, who stressed the urgent need for stabilization. But the consultation process was important to the success of the adjustment. It certainly had its flaws, but it was not a mere rubber-stamping of retrenchment measures that had already been decided: some of the proposed cuts were abandoned in the face of objections.

While income tax was accepted in principle, it was rejected for state employees; and while steep price increases were agreed for cigarettes, alcohol, petrol, electricity and some forms of transport,footnote37 those for basic goods remained fixed well below their cost, regardless of the fiscal implications. It was also confirmed that if jobs were to be shed, the process should be a gradual one, to allow redundant workers a chance of redeployment. The participation of workers in drawing up the stabilization measures meant that although job security was weakened, the commitment to preventing mass unemployment remained intact. The sudden reopening of farmers’ markets—agromercados—announced in September 1994, in the aftermath of the habanazo, also contributed to stabilization, although that was not its primary purpose. Details of discussions between government leaders have not been made public, but the decision is widely believed to have been resisted by Fidel Castro, who saw the agromercados as a ‘cultural medium for a host of evils and deformations’, and supported by Raúl and the Asociación Nacional de Agricultores Pequeños (anap, small farmers’ association) on the grounds that they could help to increase food supplies.footnote38 Again, Cuba watchers in Pittsburgh and Miami saw the reform as inadequate, as it represented only a partial liberalization of the market for agricultural produce: the state continued to play a major role in food distribution to meet its universal guarantee of basic needs. The rationing system remained in place and farmers were still obliged to supply quotas to the acopio and could only sell the surplus in the markets; the new outlets were heavily regulated, inspected and taxed. Officially, prices were determined freely by supply and demand, but the government nevertheless sought to rein them in by imposing restrictions on price flexibility and undercutting them in state outlets.

Together, these four policies brought a substantial measure of fiscal and monetary stabilization, but the nature of the adjustment contrasted sharply with that of the other ex-Comecon economies. The first difference was that, rather than reducing the fiscal deficit by cutting state spending, as happened in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, the Cuban government closed the gap mainly by increasing state revenue. Between 1993 and 1995, nominal fiscal revenue rose by 37 per cent, while spending fell by just 5 per cent. Two-thirds of the new income came from rising sales in state-owned hard currency stores, now called Tiendas de Recaudación de Divisas (trds), with the rest from new indirect taxes and user charges. The second difference was that Cuban welfare budgets remained unscathed, with the retrenchment limited mainly to the army, state administration and enterprise subsidies.footnote39 By holding nominal spending steady as gdp grew, Cuba’s government spending/gdp ratio fell from a peak of 87 per cent of gdp in 1993 to 57 per cent in 1997—although this was still far greater than the ‘transition country’ average of around 40 per cent.footnote40 In this way, Cuba managed to combine social protection with the rapid narrowing of the fiscal deficit, from 5.1bn pesos in 1993 to less than 800m pesos in 1995. This was a far more radical turnaround than that achieved elsewhere: Cuba’s fiscal deficit had averaged 30 per cent of gdp in 1991–93, compared to an average of 8.8 per cent for ex-Comecon countries; by 1995 it had been reduced to 5.5 per cent, and stabilized at around 3 per cent thereafter.footnote41

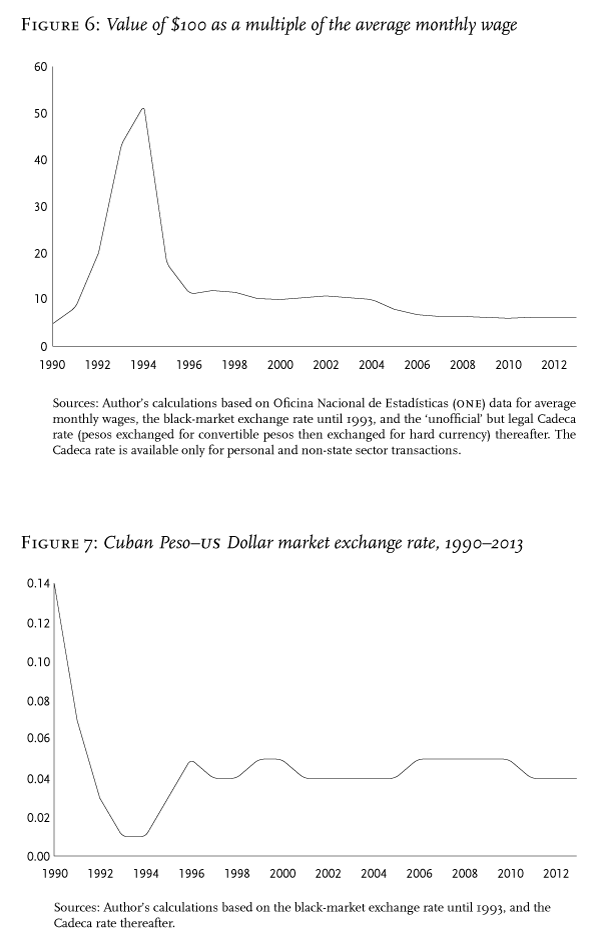

The 1993–94 measures also helped to stabilize the peso: dollar depenalization attracted new currency inflows, self-employment gave some stimulus to the supply of services, fiscal adjustment reduced the monetized government-spending deficit and the agromercados eased food shortagesfootnote42 and reduced prices.footnote43 By the end of 1994, the currency depreciation had not only been halted, but partially reversed, with a rate of around 60 pesos to the dollar: more than double its value of 150 pesos to the dollar in February 1994. Over the following 18 months it continued to appreciate, to reach 18 pesos to the dollar by mid-1996. This degree of currency consolidation has been unmatched by the ‘transition’ countries: while most succeeded in halting depreciation, none achieved a rebound.footnote44 But although Cuba’s inflation was brought under control, severe monetary imbalances persisted as the value of the peso stayed well below its 1990 level. This meant that state salaries and prices, which were held relatively stable in nominal terms, remained depressed relative to hard-currency and market prices. The undervalued Cadeca exchange rate served as a means of suppressing import demand through shared hardship over the next decade, while the government focused on the urgent need to rebuild net foreign-exchange earnings.

US enmity

Yet even as the economy stabilized, the external environment worsened. The trade embargo imposed by Kennedy in 1962 had been upheld by successive executive orders in the decades that followed. But in 1992—the depth of the período especial—it was hardened into law by the Toricelli Act. In 1996 the stranglehold was tightened further when Clinton signed the Helms-Burton Act into law, increasing penalties for third-country institutions ‘trafficking’ in former us assets, confiscated after 1959; and barred entry into the us to those who had worked for such firms. The prohibition extended to dollar payments processed through the New York exchange, even if the transactions did not involve any us entity. The Act obliged countries trading with the us to certify that their products contained no raw or intermediate materials from Cuba.footnote45

The importance given to the principle of national sovereignty and security in Cuba is readily understandable in this context. Yet it has also imposed damaging constraints on internal discussion. The Castro government responded to the Helms-Burton Act with a law ‘re-affirming Cuban dignity and sovereignty’, which made it illegal for any Cuban to divulge information, particularly on the economy, that might undermine national security. One upshot was the closure of an important research programme at the Centro de Estudias de las Americas (cea) after its researchers published the first comprehensive discussion of the Cuban adjustment in English.footnote46 This kind of defensiveness—the researchers had regarded themselves as loyal but critical revolutionaries—ultimately serves to weaken Cuba’s capacity to respond creatively to changing conditions.

3. Restructuring

With the us embargo blocking access to the finance showered upon the other ex-Comecon countries, Cuba has had to create whole new industries with extremely limited resources. The level of aggregate investment, which fell by more than 85 per cent between 1990 and 1993, has remained extremely low. According to official national income figures, by 2012 it was still only half the 1990 level, with an investment/gdp ratio of around 10 per cent, compared with an average for the ex-Comecon members of 20–25 per cent.footnote47 With such a low rate of aggregate investment, it is all the more surprising that Cuban gdp recovery and growth has been in line with the ‘transition country’ average. Policies have focused on improving foreign-exchange reserves by developing new export industries, reducing dependence on food and energy imports, finding new markets and securing alternative sources of external financing, all within the limitations imposed by us sanctions. Their relative success, in terms of the degree of restructuring achieved for the amount of financing available, can be attributed to a state-led approach of ‘picking winners’.

Attracting investment

Because of the sanctions, foreign direct investment has offered the cheapest—and often the only—way for Cuba to raise hard-currency finance. It also allows Cuban officials to hold discussions with foreign partners behind closed doors, and so avoid the attention of the us Office of Foreign Assets Control. It has faced challenges from investor suspicion, reluctance within the Cuban government—‘La inversión extranjera no nos gustaba mucho’, Fidel wryly admitted to the 1997 pcc Congress, before going on to explain its importance—and the need to adapt Cuba’s legal, financial and technical structures. Since 1990, policy towards fdi has evolved to adapt to these constraints.footnote48 The process of adjusting attitudes, regulations, accounting, arbitration, insurance and labour rules began as soon as Cuba lost its Comecon partners. Joint ventures with foreign private businesses had been legalized in 1982, and the first pilot project established in 1988; but in response to the urgent need for new agreements, fifty had been signed by the end of 1991. A constitutional reform of July 1992 redefined compulsory state ownership as applying only to the ‘fundamental’ means of production; a 1995 foreign investment law further clarified the regulatory framework.

But while the aim has been to attract new investment, the Cuban state did not relinquish control. It continued to restrict the scope of fdi, with any major transfer of state assets to foreign ownership requiring that the Executive Committee of the Council of Ministers be satisfied that it would ‘contribute to the country’s economic capacity and sustainable development, on the basis of respect for the country’s sovereignty and independence’, by providing fresh capital, new markets, technology or skills, including management expertise. Approvals have been on a case-by-case basis, and over the years many proposals have been rejected, with a process of ongoing policy review. The rules have therefore ensured that the opening to fdi has been controlled within the state-socialist system of economic management.

The evolution of fdi policy responded to changing circumstances. In the early 1990s some opportunities were missed, due to delays or misunderstandings; once they had identified the problems, the authorities sought to streamline procedures to make things easier. By 1997, import capacity had recovered sufficiently to reduce the urgent need for foreign exchange, while the Helms-Burton Act operated to deter overseas investors. As a result there was no further liberalization of the fdi regime at the 1997 pcc Congress, just an endorsement of the existing approach, specifying that capital should be sought in particular for infrastructure, mining and energy development. This was followed by a shift towards bigger projects, resulting in the non-renewal of contracts for smaller investors. Though Cubanologists lamented a policy reversal, the essential nature of the fdi strategy was unchanged. While the number of joint-venture agreements per year fell from around 40 in 1991–97 to an average of 25 at the end of the decade, larger contracts meant that the average net annual inflow of foreign capital rose from $180m in 1993–96 to $320m in 1997–2000.

This period also saw the first part-privatization of Cuban assets—in 1999 a French company, Altadis, took a 50 per cent share of Habanos, the international distributor of Cuban cigars, for $500m—and the first fully foreign-owned joint venture, a $15m power plant built by a Panamanian company. From 2001–08, fdi policy was again affected by worsening relations with the us during the ‘war on terror’—Cuba had been designated a ‘state sponsor of terrorism’ by the Reagan Administration—as monitoring and prosecutions increased. Bush Jr set up a Cuba Transition Project to plan for a post-communist Cuba and the State Department intensified efforts to detect and prosecute violators of us sanctions, discouraging foreign business interest. In 2004, Washington had imposed a $100m fine on the Swiss bank ubs for delivering a consignment of dollar bills to Cuba. Havana responded by cancelling the use of dollars in domestic transactions, though they could still be held and exchanged for cucs—with a 10 per cent surcharge. At the same time, Cuba’s relations with Venezuela were flourishing. Hugo Chávez had first been invited to Cuba as an opposition leader in 1994. After Chávez’s electoral victory in 1998—and especially after the defeat of the 2002 coup attempt and management strike against his government—trade links between the two countries were strengthened, culminating in a bilateral agreement in December 2004 that would exchange Venezuelan oil—some 53,000 barrels a day—for Cuban professional services, health workers and teachers. For the first time since 1990, Cuba received significant financing on preferable terms, lifting investment and annual gdp growth, which rose to an average of 10 per cent in 2005–07. With Venezuela, Cuba was a founding member of a new trade agreement, alba—Allianza Bolivariana para los Pueblos de Nuestra América—which came to include Bolivia, Ecuador, Nicaragua and four Caribbean island nations. Average annual export earnings growth rose to 30 per cent in 2005–07, up from 9 per cent in the previous decade.

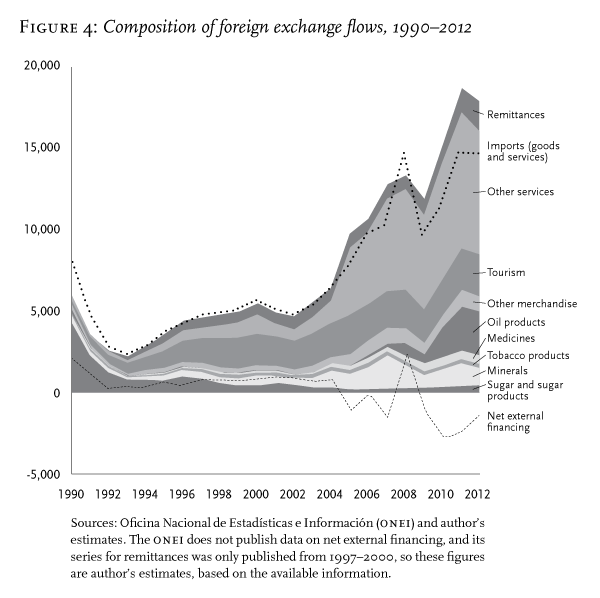

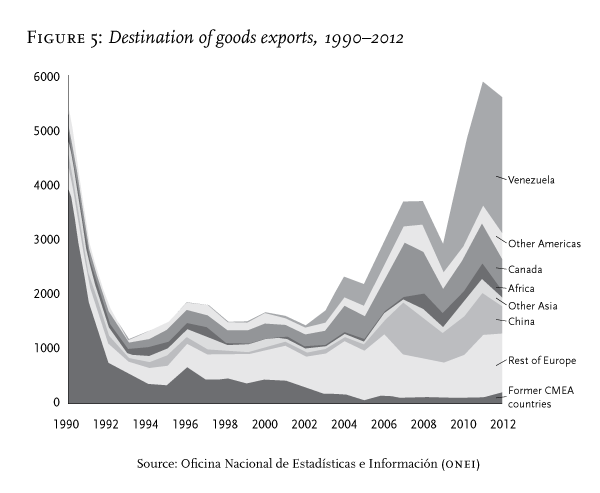

Although Cuban statistics on international capital flows are very sparse, the available evidence confirms the radical restructuring of production and international trade achieved with relatively meagre finance. Cuban fdi has amounted to only around 1 per cent of gdp since the mid 90s, compared with an average for the ex-Comecon countries in Central and Eastern Europe of around 4 per cent.footnote49 Havana succeeded in getting a high impact per dollar of capital investment by picking winners and directly negotiating contracts. Yet the result is that Cuba’s reinsertion into the global economy has been led by only a handful of industries. Figures 4 and 5, below, highlight the narrow base of Cuba’s economic restructuring and recovery since 1990. Figure 4 shows the four main sources of foreign-exchange growth since 1990: first tourism in the 1990s, then nickel and energy and, in the past decade, professional services leading the recovery. Within Comecon, sugar had accounted for 73 per cent of all export earnings; the trade deficit had been around $2bn. By 2012, sugar accounted for only 3 per cent of export earnings, while the newly developed tourism, nickel, oil-processing and professional-services industries earned enough to produce an annual trade surplus for goods and services combined of over $1bn. The tourist industry and nickel mining were recapitalized through private fdi; oil-processing and professional services through the 2004 Cuba–Venezuela agreement. The latter has made the greatest contribution to foreign-exchange earnings—indeed, earnings from the sale of professional services to Venezuela have exceeded those of all goods exports combined since 2005—although the strongest growth since 2008 has come from the Cienfuegos oil refinery, a joint venture between the Cuban and Venezuelan state oil companies. The biotechnology sector, in which hopes have been concentrated, has recently been growing at a healthy pace—exports doubled between 2008 and 2012—but, at only 3 per cent of total export earnings, it has not yet grown large enough to drive the national economy. By 2012 Cuba’s trade surplus (for goods and services combined), along with remittances estimated to have grown to around $2bn, seems to have provided sufficient foreign exchange to allow for an accumulation of international reserves, indicated by the negative balance of estimated ‘net external financing’ in Figure 4.

Figure 5, showing the geographical destination of exports, reveals the extent to which Cuba’s goods trade has been reoriented. In 1990, some 75 per cent of exports were sold to former Comecon countries, but by 2012 these accounted for less than 5 per cent. Around 2000, Cuba had succeeded in achieving an unprecedented degree of export-partner diversification, with Western Europe accounting for 32 per cent of the total, former Comecon countries for 27 per cent, Canada for 17 per cent, Asia for 12 per cent, and the rest of the Americas—excluding the us, which remains closed to Cuban exports—a further 10 per cent. Since then, dependence on a single partner has once again increased: by 2012, Venezuela accounted for not only 45 per cent of goods exports—much of this being oil products from the Cienfuegos refinery—but also most of Cuba’s non-tourism services.

4. Raúl’s Reforms

The surge in foreign-exchange earnings in 2005–07 through trade with Venezuela brought welcome relief. But by the time Raúl Castro and his team had formally assumed office in 2008, the surge had ended. Three highly destructive hurricanes and the fall of nickel prices following the world financial crisis eliminated the trade surplus and drained foreign-exchange reserves, leaving Cuba unable to meet its debt obligations. Though social protection was intact, the money supply had been stabilized and fiscal discipline secured, it was clear that it would take more than the recovery of foreign-exchange earnings to allow the Cuban peso to return to its former level and thus restore the real value of wages, benefits and prices. The monetary imbalance had become entrenched; the co-existence of two sets of prices, incomes and exchange rates, state-administered and market, blocked integration between the domestic and external economies, resulting in a lop-sided and distorted structure of production. In real terms, Cuban state salaries had remained below their 1990 level for many years, with the Cadeca exchange rate now at 24 pesos to the dollar, compared to the former black market rate of 7 pesos in 1990 (Figures 6 and 7). Inequality and perverse incentives persisted. Only a small, privileged portion of the population with access to hard currency could afford to shop regularly in the free markets; for the rest, the ‘trickle-down’ benefits from the new non-state sector were weak and indirect, coming mainly through the collection of taxes used to finance welfare spending.

As well as widening inequality, the bifurcation of the economy had hampered development through the growth of a parasitic informal sector, which drained resources from the formal economy by offering incentives for skilled workers, including teachers, to take low-skilled jobs for cuc wages and encouraging the pilfering of state resources, for re-sale on the black market at high prices. The prevalence of corruption and widening income inequality had progressively undermined egalitarian ethics and the credibility of socialist rhetoric, an effect compounded as richer Cubans could now secure preferential access to jobs, education and health by paying for the privilege through informal channels. Meanwhile the cost of subsidies consumed funds that might otherwise have been used for investment.

Lineamentos

The first problem for Raúl Castro’s new team, led by Economy Minister Marino Murillo, was to restore the external balance, after the shocks of 2008. This was achieved by a sharp reduction in imports, which cut official gdp growth to just 1.4 per cent.footnote50 Since then, economic strategy has been defined as ‘updating’ the model—diversifying production, reanimating the decapitalized domestic economy, and realigning prices, exchange rates and incomes—rather than launching a Chinese-style process of capitalist accumulation under Communist Party leadership. Although Raúl’s style of leadership is very different from his brother’s, he has been careful to link this overhaul to Fidel’s policies, by repeatedly using quotes from his speeches, a favourite of which has been ‘Revolución es sentido del momento histórico; es cambiar todo lo que debe ser cambiado’.footnote51 After some modest initial reforms, Raúl prepared the ground for a more radical approach by launching a further national debate in the run-up to the Sixth Congress of the pcc in April 2011. A draft document, ‘Lineamientos de la Política Económica y Social del Partido y la Revolución’, was circulated in November 2010 for discussion at meetings around the country, where comments and proposed revisions were noted. A redrafted text was submitted to the Congress, amended and then published in May 2011.footnote52 Although these ‘Guidelines’ were intended to direct policy until 2016, the document was nothing like a five-year plan. Like the pcc’s 1991 resolution on the economy, it outlined a set of principles and objectives, rather than setting out a reform programme.

For all the shortcomings of the Cuban participation system, it continued to serve as both a constraint and a driver of official policy. This was illustrated by the way in which a directive for large-scale public-sector layoffs was reviewed and revised, with the participation of the official trade unions, after state employees pushed back against the over-hasty pace of adjustment and the unworkable and inequitable way in which it was implemented. The events demonstrated that, though by no means ‘independent’, Cuban trade unions played an important part in establishing policy limits and in the practical application of ‘rationalization’ or enterprise closures.footnote53 The consultation process on the ‘Guidelines’ also provided an opportunity for public scrutiny, resulting in some significant adjustments to the final document. And while implementation since May 2011 has been centrally coordinated by a commission under Murillo’s leadership, with regular reports on progress dutifully presented to the Party and National Assembly, it has involved a much wider range of agencies, with complex interactions between party, government and expert commissions. The implementation process has included an array of experiments and pilot schemes, as well as retraining, research and monitoring programmes.

The ‘Guidelines’ and official speeches make plenty of references to ‘using the mechanisms’ of the market, but regard this as a component of state-directed policy, in contrast with the neoliberal doxa that have underpinned ‘transition’ strategies elsewhere. The measures taken so far have involved liberalizing elements, including expansion of the non-state sector, wider scope for foreign investment, tax concessions for special development zones and deregulation of the housing and second-hand car markets. But rather than surrendering control of the economy to the private sector, the government has accompanied these moves with measures explicitly designed to strengthen state oversight. Since Raúl assumed the presidency, he has increased the resources and authority of the Comptroller General, Gladys Bejerano, a key figure who has consistently been overlooked by outside commentators. The work of the Comptroller General has not only been aimed at strengthening anti-corruption efforts—with attention focused on the most pernicious high-level abuses, leading to long prison terms for some senior officials—but also at improving tax compliance, through the dissemination of information and a major nation-wide training programme for officials, managers, accountants and the self-employed. That is, using the institutional assets of the state to build the apparatus and culture required to bolster efficiency and equity in the formal sector, in which markets are playing a greater role than before.

Cuban economic performance since the global financial crisis has been weaker than expected, with average annual gdp growth of less than 3 per cent, repeatedly missing targets. Aid from Venezuela continues, but the initial boost this brought has levelled off since 2008, and Cuba’s continued exclusion from the us market and most sources of international finance remains a drag on growth. There has been little improvement in real wages in the state sector, apart from the health-service workers who saw a hike in early 2014. A particular disappointment has been the lack of any significant upturn in agricultural output, despite the distribution of land to private farmers and a series of measures designed to improve their incentives, distribution networks, supplies of inputs and the availability of finance. In comparative perspective, Cuban gdp growth has been no worse than the average for ‘transition’ countries since 2008, despite a substantial reduction in public-sector payrolls; the adjustment has been kept slow enough to prevent a demand shock or to create a sharp rise in unemployment. But the results fall short of the improvement expected from the 2011 reforms. Beyond tinkering with regulations to make the new markets work better, bolder moves are now being considered to increase foreign investment and to tackle the persistent difficulties created by the dual-currency system.

The most important recent initiative has been the upgrade of the port of Mariel, 45 km west of Havana. The project, a joint venture begun in 2009 and financed by a $1bn loan from the Brazilian development bank, bndes, is the largest infrastructure investment since 1990. The harbour now has a draught of 18 metres, deep enough to accommodate the giant ‘post-Panamax’ container ships that will pass through the Panama Canal when it is completed in 2015. At present, the us embargo not only bans all imports from Cuba, but also bars ships that have been to Cuba from docking in us ports for 6 months; activity at Mariel would clearly multiply if these restrictions were even partially lifted, and in part the project may have been designed as a signal of Cuba’s interest in improving bilateral relations. But even without the us, the facility is ready to service growing trade between China, Brazil and Europe, as a hub where containers can be transferred to smaller ships for transport to regional ports.

A second initiative, the opening of a Special Development Zone at Mariel in late 2013, linked by a new railway line to Havana, is intended both to promote an industrial ‘cluster’ geared to export processing around the port and to attract Cuban and foreign companies serving the domestic market. Accompanying both these developments is a new foreign-investment law, taking effect at the end of June 2014 after many years of discussion. To the disappointment of Cubanologists, this is only a revision of the 1995 legislation: while there are adjustments to taxes and other incentives, and a more explicit invitation to us-based investors, the central principles remain: the Cuban state will be the gatekeeper and must be satisfied that each foreign investment contributes to its developmental objectives.

Day Zero

Nevertheless, success in attracting foreign investment can only perpetuate a distorted growth model, as long as the gap between exchange rates—the ‘official’ rate of peso–cuc–dollar parity, and the ‘unofficial’ but legal Cadeca rate of 24 pesos to the cuc/dollar—creates a range of official, unofficial, dollar and non-convertible peso price sets, which prevent integration between the domestic and external economies. As the non-state sector has developed, it has become increasingly clear that relatively inefficient private enterprises have been able to prosper within the domestic economy, as their Cuban peso costs, including labour, are undervalued at the Cadeca/cuc rate that they use for their transactions. In effect, the Cuban state is subsidizing the new non-state sector through the undervalued Cadeca rate. Meanwhile, state enterprises have to use the overvalued official rate, a severe disadvantage in terms of their competitiveness. A form of ‘money illusion’ means that efficient state enterprises report losses and so cannot raise capital for investment, while private entrepreneurs operating at very low levels of productivity enjoy hefty hidden state subsidies but complain of being over-taxed.

Guideline 55 of the 2011 ‘Lineamentos’ clearly states that the dual-currency system needs to be tackled, but the wording is cryptic and change has been slow to arrive.footnote54 The delay is partly attributable to risk aversion. Any currency realignment will involve a disruptive re-valuation and, in the wake of the peso’s extreme collapse in the early 1990s, the Central Bank has focused on maintaining stability. Fear of renewed hardship has created a preference for caution, not only within the government and bureaucracy, but also within the population as a whole; many households have adapted to the distorted price structures, and have therefore become dependent on them. Between the mid 90s and 2008, the perception of gradual improvement through adjustment was sufficient to dull the imperative to restore balance to the monetary system; but the subsequent slowdown has brought the issue to the fore.

Finally, in early 2013, the first moves were made. After two years of study, a pilot programme began to allow some state enterprises to use cup–cuc rates of around 10 pesos to 1 cuc for purchases from domestic suppliers—state, cooperative or private. In October 2013, the government announced that a timetable for currency reform had been drawn up. In March 2014 it published detailed instructions for setting prices and settling accounts on ‘Dia Cero’—day zero—when the cuc will be abolished.footnote55 The Cuban peso will then presumably become directly convertible into foreign currency, though details of any planned exchange controls are not yet known. In order to minimize disruption, the state will set parameters for new Cuban peso prices and would provide subsidies to cover initial losses; the new prices, denominated in the single currency, would then reflect the loss of the peso’s international purchasing power since 1990, and the ‘hidden subsidy’ to the private sector would be removed.

The vital issue of what the new, single exchange rate will be has not yet been specified. The existing Cadeca rate of 24 pesos to the dollar—which undervalues the peso—might seem to be the least disruptive and, through its huge devaluation of the official exchange rate, it would radically improve the competitiveness of the enterprise sector. But it would insert the Cuban economy into the global market as an extremely low-wage producer and establish an inordinate gap between ex-cuc incomes and Cuban peso pay scales. A rate of 20, 15 or even 10 pesos to the cuc/dollar would offer a partial correction in relative real incomes, while also improving competitiveness and allowing for a further adjustment once things have settled and confidence has been restored.footnote56

At the time of writing, no date for Dia Cero has been given, and there is still no certainty about how a revaluation of the peso would be managed. By approaching the process of currency unification with caution, the government is clearly hoping that it will be possible to minimize the costs of price realignment. There are no directly comparable cases to the Cuban one, because currency unifications in other countries have been conducted either when positive trade balances have provided plentiful foreign exchange, or with external backing; and none have shared Cuba’s particular structure of fragmented markets and prices. Without the monetary data needed to understand Cuban conditions fully, we can only speculate about the likely impact of the change. But it seems clear that this reform will have far-reaching consequences over the next few years, not only for relative prices and income distribution but also for the dynamics of Cuban economic growth.

Social divisions

It is not easy to assess what proportion of the population has access to cucs or foreign currency, and in what amounts. Some estimates suggest that half the population have some cucs, but in many cases the sum will be very small. The concentration of savings in bank accounts is very high—but those with successful black-market businesses, for example, keep their money elsewhere. What can be identified with some certainty are the social groups that have most access to cucs, and those which have none. The poorest are those who depend on state pensions or social assistance, without family support. The pensions are barely enough for subsistence, so social services have to supplement them where there is no family, or the family is too poor. Although there is more money around in Havana, and therefore more opportunity for the young and fit to earn something, for old people unable to move about it may be one of the worst places, because market prices are highest. People doing very low-paid state jobs, without access to bonuses, opportunities for pilfering, jobs on the side or remittances, also remain close to subsistence.

The next-worst off—probably more than half the population—are those who manage to get by because they can supplement their state incomes in some way, but live hand-to-mouth and don’t have enough to save. Government officials are in this category, which also includes those living off modest remittances or engaged in small private activity, legal or illegal. Wage differentials are significant, but they are not the main determinant of real consumption; that depends on access to cucs. Some of the hardest-hit state employees have been pcc members and officials, who are not supposed to engage in any unofficial activity. They may have privileges in kind, but not in income. For some professionals, work trips abroad can provide the opportunity to obtain extra money for large items, such as house repairs. As time has passed, the proportion of state workers receiving some kind of bonus has grown. First, there were monthly javas, or bags, of basic goods, such as bleach or toothpaste; now bonuses of 10–25 cucs or more are common. Over the past decade, the incomes of a growing number of households have increased enough to get a mobile phone, improve their homes or buy a second-hand car. But nominal state incomes have not risen in line with the cost of living, so anyone still relying on a peso salary alone remains very hard-up.

The rich minority is a separate group. They are the few people receiving generous remittances, some private farmers, the few successful owners of illegal or legal non-state enterprises, international sporting or cultural figures, corrupt enterprise managers and the occasional corrupt public official. That is, they do not get their privilege from peso incomes paid by the Cuban state. They live in a different world to the majority of the population. Policy towards this group is to try to detect and punish economic crime and to strengthen the tax system, to ensure that high incomes are heavily taxed, both through income and retail taxes; but the government is abandoning any attempt to prevent high incomes derived from legal activity. Thus restrictions on baseball players going to play abroad are being lifted, and Cubans are now freer to travel abroad to work and then return.

For the majority, though, improvement in living standards has been slight and painfully slow; made all the more difficult to bear—especially in Havana—because they can see the comforts being enjoyed by others, often not earned from honest toil. Basic commodities are still subsidized, but some staples have been removed from the ration and have to be bought in the agro-markets. This has been a gradual process, accompanied by a slow rise in nominal salaries and an extension of bonuses. Power supplies have improved, but there have been increases in utility prices for water and electricity, which tend to cancel out the rise in wages; so for many people, the improvement in living standards is barely perceptible. Yet the safety net remains in place, and infrastructure and public services are certainly better than before, reflecting the government’s priorities for spending new income streams from taxes and exports of professional services.

An alternative?

Raúl Castro’s second and final presidential term will end by 2018 at the latest. By 2016, when the five-year process of ‘updating’ under the current Guidelines comes to an end, the aim is for the economy to have a broader productive base and a larger private sector, while retaining universal health, education and welfare provision. To achieve this, the rate of investment will need to rise. Given Cuba’s success in cultivating official relations with new partners, including China, Brazil and Russia, the aspiration to increase the flow of foreign investment seems feasible. The trickier task will be to raise efficiency and dynamism within the domestic economy, while preventing widening income gaps and social divisions that threaten the state-socialist project.

Before writing off Cuba as a spent force, the magnitude of its achievement to date should be acknowledged. While conceding that market mechanisms can contribute to a more diversified and dynamic economy, Cuban policymakers have not swallowed the promises of full-scale privatization and liberalization, and have always been mindful of the social costs. This approach, shaped not least by exceptionally difficult international conditions, has been more successful in terms of both economic growth and social protection than Washington Consensus models would predict. Comparing Cuba’s experience with that of the former Comecon countries in Eastern Europe—or indeed with China and Vietnam—it is possible to identify some distinguishing features of its path.

First, Cuba was able to maintain a social safety-net during the crisis, in sharp contrast to the others. In the context of the island’s uniquely severe exogenous shock and hostile external environment, a commitment to universal welfare provision undoubtedly served to limit social hardship. Linked to this has been the process of extensive popular consultation, particularly at three critical moments—the onset of the crisis, the stabilization process, and the prelude to Raúl Castro’s new adjustment phase. Third, by retaining control of wages and prices during the early period of shock and recovery, it was possible to restore stability relatively quickly by restraining an inflationary spiral. Although fixed wages and prices created the conditions for a flourishing informal economy, they also served to minimize disruption and limit the income gap within the formal economy. Though the two are quite distinct, the strategy bears comparison with China’s ‘dual track’ system, in which the ‘planned’ track is maintained while a ‘market’ track develops alongside, providing opportunities for experimentation and learning. For all its inefficiencies and confusions, Cuba’s ‘bifurcation’ and ‘second economy’ played a part in adjustment to the new conditions.

Fourthly, the state retained control of the process of economic restructuring, allowing it to channel the very limited hard-currency resources to selected industries, achieving a remarkable recovery of foreign-exchange earnings relative to the amount of capital available. These enterprises also served as ‘learning opportunities’ for Cuban planners, managers and workers to think through how to adapt to altered international conditions. The export base created by this approach may be too narrow to drive sustainable growth over the long term, but it was an efficient way to restore capacity after the crisis period. Finally, Cuba’s rejection of the mainstream ‘transition-to-capitalism’ route allowed space for a process of adjustment—described by one official as ‘permanent evolution’footnote57—that has been flexible and responsive to Cuba’s changing conditions and constraints. This contrasts sharply with the more rigid recipes for liberalization and privatization pedalled by the hordes of transition consultants in other former Comecon countries. Cuba is a poor country, yet its health and education systems are beacons in the region. Its approach has shown that, despite contradictions and difficulties, it is possible to incorporate market mechanisms within a state-led development model with relatively positive results in terms of economic performance and social outcomes.

This raises the next question: why should we assume that the state will withdraw from its dominant role within the economy, or that the current approach to policy must eventually give way to a transition-to-capitalism path? A fundamental assumption of transition economics has been Kornai’s claim that ‘partial alteration of the system’ cannot succeed; efficiency and dynamism will only be maximized when the transformation from a ‘socialist planned’ economic system to a ‘capitalist market’ one is complete, because the former is too inflexible to survive over the long term. But the experience of former Comecon countries has demonstrated that success is far from guaranteed and that social costs can be high. Viewed without preconceptions, the Cuban case suggests that another way might be possible, after all.