In 1840, a coalition of European powers decided to take on an alarming problem to their south.footnote1 The Albanian-born governor of Ottoman Egypt, Mehmed Ali, had spent the past two decades building up a formidable industrial and military capacity in his assigned territories. A veteran of the Napoleonic wars, the Wahhabi revolt and the Greek rebellion, Ali administered Egypt as a province of the Sublime Porte in name only; in reality he was forging a Mediterranean Prussia. Ali’s troops marched on Palestine, Syria and then Greece, claiming territory and stationing men. The Ottoman Sultan could do little about it. Eventually, British and Austrian navies cut off Egyptian supply lines and entered Alexandria’s waters. Under duress, Ali signed a series of capitulations which opened Egyptian markets, dismantled its manufacturing base and defanged its military. Egypt experienced rapid under-development, becoming an exporter of raw commodities and an importer of European manufactures for the next century.footnote2 It was not until the rule of Gamal Abdel Nasser that such statist attempts would occur again in North Africa, to be met once more with external military response. Today, not coincidentally, Egypt lags behind other middle-income states in industrial capacity, as well as being the world’s largest importer of wheat.

Amid these nineteenth-century efforts at geopolitical renewal, Egyptian intellectuals attempted a synthesis of Islamic political thought and European political economy. Writing in 1869, Rifa’a al-Tahtawi hoped that the development of labour in Egypt and other Muslim states might speed ‘the advancement of societies’.footnote3 Qasim Amin’s The Liberation of Women and The New Woman appeared not long after. Though the actors have changed since Tahtawi and Amin discussed the relation of emerging social formations to state building, the debates over the prospects for regional order, popular cohesion, and political rejuvenation remain largely unaltered. To chart the historical terrain, this essay tracks the making and unmaking of social compacts and state formations in the Middle East and North Africa (mena), amid changing political-economic conditions, across five broad chronological periods: the tail end of the Ottoman and Persian empires, the colonial interlude, the era of political independence, the infitah years of economic opening, and the current upheaval of unrest and militarization. Despite the lack of settled conceptual or geographic definitions for the region, certain patterns can be discerned.

1. empires unravelled

Few zones of the world have been so riven by opposition, real or imagined, for as long as Europe and the Middle East. Most recently, the institutional turn in economics has produced attempts to explain anew the divergence of socio-economic trajectories between them. These accounts focus on the persistence of ‘bad’ institutions in mena areas over the longue durée—lack of primogeniture, for instance, or dominance of state rulers over local elites.footnote4 Yet economic historians of the region counter that, in reality, institutional pluralism, not uniformity, was the rule. Land tenure patterns ranged from small peasant holdings to tax farming by notables to imperially administered estates. Commerce and credit tended to flow through and between urban locales, overcoming or bypassing religious dictates against usury through flexible interpretations of scripture; the roles of women and religious minorities as traders were not insignificant. Nomadic tribal confederations ranged across large swathes of the region, coexisting within and around agrarian empires and their urban metropoles. The ‘gunpowder empires’ of the early modern period—as Marshall Hodgson termed the Ottomans and Safavids—more successfully centralized a ruling apparatus and market penetration over large territories compared to previous centuries. Long before Western colonialism, the internal and external borders marked out by these and subsequent warring empires laid the foundations for twentieth-century state-building in the mena region.

As elsewhere, the internal authority of these empires was irregularly exercised. By the end of the eighteenth century, merchants, artisan guilds and religious endowments tended to administer most social aid and welfare in imperial urban zones. Charitable giving was, of course, an Islamic injunction. Through the pooling of donations and assets under religious endowments, Hodgson noted, ‘various civic essentials and even amenities were provided for on a private yet dependable basis without need or fear of the intervention of political power’.footnote5 Yet the few studies that exist show that inequality was quite high in West Asian empires. The Gini index during the eighteenth century for sampled records in Cairo and Damascus hovered around 0.75, while northern Anatolian locales stood at 0.60.footnote6

Increased commercial trade with the capitalist world-economy and penetration by European merchants and militaries did not have a single, generalized effect on social structures in the region. The variation of peasant tenure patterns, merchant–state relations, and artisan guild politics differed widely, based on relations between local elites and imperial centres. Hardly the paragon of ‘Asian despotism’, Ottoman capacity for state regulation was in fact limited and had reached its apex in the sixteenth century. Most revenues were kept by tax-farming notables, while merchant entreaties against foreign competition from European trade went largely unheeded.footnote7 The re-centralization of the Ottoman bureaucracy through nineteenth-century reforms brought the state back into social regulation and class formation, most notably in Mehmed Ali’s Egypt and the wealthier Ottoman provinces. A mixed economy of state relief took shape, linked to military buildup and urban policing.footnote8 The Persian Empire under the Qajar dynasty fared worse at fiscal-military centralization, as evidenced by a series of famines during the 1860s–70s. During these catastrophes, an imperial ban on cereal exports was mandated but unenforceable. Most of the famine aid came from European missionaries, not the imperial government in Tehran, and was directed towards religious minorities.footnote9

Given the unevenness of state penetration combined with social deprivation, it is not surprising that unrest broke out. The nineteenth century witnessed a wave of uprisings on mena imperial peripheries, led by men whom Eric Hobsbawm would have instantly recognized as primitive rebels: the Sudanese Mahdi, the Daghestani Imam Shamil, the Shirazi Bab (precursor to Baha’ism), the Sokoto’s Usman dan Fodio (between Lake Chad and the Niger River), or the Somaliland’s Mohammad Abdullah Hassan (the original ‘Mad Mullah’). These were generally millenarian movements which devised radical worldviews and appealed to social justice under the guise of Islamic tradition. Whether quickly extinguished or successfully converted into proto-states, their presence was often a pretext for the intervention of Western colonial armies.

The inability of mena empires to confront external and internal challenges spurred urban intellectuals to argue for more radical social and political measures to be carried out by the state. Along with other agrarian empires such as Russia, India and China, the Ottomans and Persians underwent anti-imperialist revolts in their urban centres in the early twentieth century.footnote10 The dynamics were similar: elites attempted to redirect their remaining imperial resources towards military upgrading, popular mobilization and nationalist myth-making, often combined with a degree of emancipation for women of the elite, at least.footnote11 It is not a coincidence that the first successful attempt, Kemalism, occurred at the heart of West Asia’s imperial arena. The mena social compacts of the mid-twentieth century owed much to its example.

2. colonial interlude

The exercise and profile of European power in the Middle East and North Africa varied by sub-region. The British pushed Napoleon’s army out of Egypt, but the restored Bourbons entered Ottoman Algeria in the 1830s and forcibly integrated territory into the French state. In contrast with Sub-Saharan Africa, inter-imperialist rivalries slowed the formal usurpation of power across much of the region. The British viewed a contained Ottoman Empire as a useful bulwark against Russian expansion. Tunisia only fell to French gunboats in the 1880s; the Moroccan Sultanate, which had always maintained independence from the Ottomans, was partitioned into French and Spanish protectorates in the 1910s. The priority of British imperial policy in the mena expanse was geopolitical control over travel routes to South and East Asia. Largely for this reason, the Persian Empire slowly lost territory during the nineteenth century to Russian and British incursions, but never formal independence.footnote12 In fact, there was only one colony established over two centuries of European imperialism in the region—the port of Aden on the Yemeni coast, ruled as part of British India.

European capital was less hobbled. French and British banks financed Ottoman state reforms in the mid-nineteenth century, which put them in sound position to acquire assets and land after the Ottomans defaulted. Eventually a European consortium took over Ottoman finances, an arrangement unsurprisingly favourable to creditors.footnote13 The vehicle of debt arrears furthered British machinations for control over the Suez Canal and indirect rule in Egypt and Sudan. As with Iran, the Maghreb region from Morocco to Egypt was racked by famine in the 1870s.footnote14 A prime culprit was the shift to monocropped agriculture—usually wheat and cotton exports—which then suffered from American competition and declining terms of trade during the global depression of the late nineteenth century.footnote15 Yet even amidst minor British and French imperial efforts at fostering plantation agriculture, a small landholding peasantry existed throughout most of the Ottoman empire into the early twentieth century.

A crucial analytic point for the mena region, then, is that European imperialist penetration of political and social structures was highly uneven. So was Ottoman rule, of course—some stretches of the Libyan coast were limited to trading posts for warding off Bedouin raids. After the Ottoman Empire shattered in World War I, some areas were ruled by colonial administration, others in an indirect fashion, while others still won formal independence through rebellion. Though in vogue, it is hyperbolic to believe that a Franco-British colonial order created the modern Middle East; such an order rather cobbled together structures of rule out of a diverse Ottoman-Persian imperial zone. As this zone collapsed in on itself during the early twentieth century, elite-led nationalist movements of both minority and majority varieties—Greeks, Serbs, Armenians, Kurds, Turks, Arabs, Maronites—manoeuvred among the ruins.footnote16 Some of these intelligentsias converted into state rulers; others formed the transnational diasporas which today reside in Western metropolises.

The inter-war period brought together the challenges of external colonial imposition and domestic political rejuvenation in contradictory ways. In British and French-administered territories, such as Egypt or Syria, nationalist elites mobilized on social as well as political grounds. In areas where the colonial question was largely settled, as in inter-war Turkey or Iran, splits appeared earlier between nationalist elites and labour movements.footnote17 Unlike Latin America, where the inter-war years provided a spur towards industrialization, in European-controlled mena the emphasis was on regulating the safe flow of goods through the region. Early oil discoveries in Khuzestan, Baku, and Kirkuk added to such imperatives. But though the geopolitical priority remained control over transit, inter-European rivalries allowed for the acquisition of capital goods in trading zones. Industrial production finally resumed in the late 1930s as another world war loomed, leading to increased proletarianization in urban centres. Domestic capitalists could prosper in the interstices of supply flows, which ramped up during the Second World War. The Allied logistics chain was managed by the Anglo-American Middle East Supply Centre, which legitimized an imperialist Keynesianism of sorts in places such as Egypt and Syria through economic planning and public-goods programmes.footnote18 Ironically, while in the newly formed nation-states of Turkey and Iran, a Bismarckian state-led development project had commenced under the guise of an anti-imperialist push for independence, similar processes were occurring under colonial administration. In contrast to the independent states, however, less was spent on welfare and public works by colonial elites, and nascent industrial drives remained based in enclave areas.

The period from the 1900s to the Second World War forged another of the great ironies of modern Middle Eastern history. Amidst crises of domestic authority, transnational networks of intellectuals—religious and secular, liberal and communist—created a common set of frameworks for nation-building, myth-making and post-colonial citizenship; industrial Japan was a widely held exemplar. Yet their eventual success in fostering coherent nation-states out of imperial clay would result in the erasure of the memory of their own roles. Transmissions of pamphlets, labourers and revolutionaries along the paths of Istanbul–Baku–Tabriz or Cairo–Damascus–Baghdad were only possible in the cosmopolitanism of a late-imperial milieu. Bolstered by armed uprisings and mass organizations, these energies would pour into the containers of the nation-state over subsequent decades. Yet once the actual work of state-building commenced, political theory was not easily translated into practice. If there is a common lesson for mena states in the inter- and post-war periods, it is the failure of elitist liberalism and the success of popular mobilization for the purposes of state-building. With a freer hand, Kemalist Turkey and Pahlavi Iran had already engaged in such efforts during the 1930s. The Wafd Party in Egypt achieved popular appeal while under British protectorate status, but focused doggedly on independence at the expense of a radical mass agenda. In the inter-war period European left movements were of little help; the 1936 French Popular Front government refused independence to Syria, Lebanon or Algeria.footnote19 Once decolonization set in, however, a region-wide social compact began to coalesce. To map out its contours, a contrast with Latin America is useful. During the 1930s rise of populist states in Brazil, Argentina and Mexico, public goods and social citizenship were extended de jure to the entire citizenry. Latin American elites crafted nationalist appeals to mestizaje or racial democracy, which attempted to reverse the stark colonial legacies of ethno-racial classification under slavery and indigenous servitude. Yet de facto distribution of these public goods tended to fall along pre-existing hierarchical lines of social distinction. The unequal access to basic health, education and infrastructural improvements led to the notoriously high inequality observed within much of twentieth-century Latin America.footnote20 In the mena region, the opposite occurred, due to the post-war configuration of state formation though corporatism.

3. postwar corporatist compact

Initially welcomed by newly independent states, post-war us hegemony was double-edged in the mena region. On the one hand, the lack of major us corporate interests compared to Latin American markets meant that us policy makers largely encouraged import substitution and aided state-led development during the 1950s and early 1960s. On the other, the us geopolitical strategy of securing favourable access to oil resources through informal alliances laid the foundation for a subsequent direct militarization of vital mena areas. The Cold War context and its coalescing divides masked a widely shared approach to social compacts in the postwar era. No matter the ideological sheen, state-led planning amidst scarcity of capital ruled the day.footnote21 This was the context for nationalization projects from Nasser in Egypt to Mossadeq in Iran.footnote22 Resources could be mobilized through manoeuvring among Cold War alliances, but claims of a distinctive model of ‘Arab socialism’ were partly aimed at warding off or co-opting the growing power of left-wing movements.footnote23

The Turkish example loomed large. In response to the chaos of Ottoman collapse and domestic radical upsurges, the new Kemalist Republic forged its own authoritarian version of Polanyi’s ‘double movement’ in the 1930s and 40s: Soviet-inspired five-year industrialization plans, Italian-inspired corporate labour control, and us-inspired distribution of state lands to middle peasants and large landowners. As a result, the decentralized land-tenure patterns in Ottoman Anatolia were preserved, even into the 1960s.footnote24 For the new nation-states of the mena region, this corporatist model of industrialization allowed an emergent political class to undercut the power bases of economic and social rivals. Iran’s Pahlavi monarchy built up a military and bureaucratic corps in the 1930s, a concentrated industrial class in the 1960s, and only afterwards began to force landowners to divest their holdings of village lands.footnote25 The Shah compared what he labelled Iran’s 1960s ‘White Revolution’ with the examples of Meiji Japan and Bismarckian Prussia.

Other countries followed the same route in speedier fashion, thus appearing all the more radical. In contrast to Anatolia, land enclosures by tribal chiefs and landlords in Egypt, Iraq, Tunisia and greater Syria had intensified during the early-twentieth century imperial breakdown. The longevity of new Arab states, therefore, was connected to how their leaders dealt with the rural question. Sixty per cent of the Egyptian peasantry was landless in 1950, with the same ratio in Syria, while Iraq’s tribal areas were racked with peasant revolt. In Algeria, an extreme case of proletarianized rural wage-labour policed by colonial arms remained in existence. These were not traditional social structures inherited by postwar states, but rather a product of rapid consolidation by local agrarian elites which dislocated segments of the population. As Hanna Batatu explained, ‘Extensive tracts of state domain and communal tribal land passed into the hands of new men of capital, European colons, ex-warring shaykhs, or retainees of ruling pashas, often through forced purchases or without ground of right or any payment whatever’.footnote26 Under this politics of notables, sometimes with liberal-democratic guises, peasants were displaced from kinship networks and communal mechanisms of social reproduction. Amid these fraying ties, the revolutionary Arab state promised to step in: Egypt in 1952; Tunisia in 1957; Iraq in 1958; Algeria in 1962; Syria in 1963; Libya in 1969—not to mention revolutionary guerrilla movements in Oman, Lebanon, Yemen and Jordan from the late 1960s onwards. To a large extent, the social origins of this new power elite were rural or provincial; they were led by men who had risen up through military and other state institutions. The goal was not a peasant insurgency, however, but a Kemalist revolution to be carried out by bureaucrats from above.footnote27 Democracy was largely seen as a divisive distraction from the task of state consolidation.footnote28

The cleavages had been drawn during the tumult of colonial rule, both consolidating the power of landed elites and expanding the strata of civic and military cadres. These processes have often been jumbled together under an umbrella category of clientelism or neo-patrimonialism, sometimes claimed to be a fixed legacy of Ottoman Sultanism in Arab lands. But as James Gelvin notes, this line of argument tended to reveal more about mid-twentieth century historians and social scientists than about the region itself.footnote29 As Gelvin saw it, Arab corporatism was a form of class warfare, not between capital and labour but between the new state elites and the old, oligarchical landed classes. To some degree, the repressive apparatus of many mena states stems from this rapid and stealthy capture of political power by men of rural lower-middle-class backgrounds such as Nasser and Hafez al-Assad. Forever paranoid about retaliation by enemies, real or imagined, security forces were first deployed against the ‘feudal’ elite and subsequently marshalled against any perceived threat of ouster.

Inherited from colonial gendarmes or carved from newly independent national armies, intelligence agencies in postwar mena states professed an enthusiasm for internal military rankings and the exuberant use of force. Deployed by leaders against the military to ‘coup-proof’ the regimes from the 1970s onwards, security agencies proliferated across the mena region to monitor the army and other segments of the state as much as the public. Linked solely to ruling families or long-serving presidents, armed to the teeth in domestic deployments against leftist and Islamist groups, states multiplied their surveillance agencies (and payrolls) in tandem with expansion of public industries and corporatist associations. One exception should be noted: unlike Morocco’s 1970s assaults on the Western Sahara or Algeria’s 1990s dirty war against Islamist contenders, Tunisia under Bourguiba had eschewed territorial expansion and military buildup to match its fearsome internal security state. This lack of relevance in internal politics meant that, post-2011, the Tunisian military preferred organizational autonomy to intercession in political dynamics after Ben Ali’s hasty escape.footnote30

The incorporation of peasant, worker and professional strata into state-linked bodies provided a countervailing social base from which to break up landholdings and dismantle mercantile networks. As a result, rural peasants were not emancipated as a class, but many of their children ended up in public employment in the city. A key outcome of the corporatist model—ideological patinas about rule of the masses aside—was the provision of rapid upward social mobility for select individuals. As Gilbert Achcar stressed, ‘the state went so far as to largely substitute itself for the private sector by means of both far-reaching nationalization programmes and massive public investment’.footnote31 The average annual rate of manufacturing growth among mena states was 13.5 per cent in the 1950s and 10.6 per cent from 1960–73. In the realm of social protection, non-state charities and philanthropies of the liberal inter-war period—schools, workshops, clinics—were eventually taken over by the state and homogenized.footnote32

This social compact involved a huge push in credentialing citizens through education and high-status professional-technical employment, still marked in the high acclaim attached to the title of muhandis (engineer) in nearly every social setting from dinner conversation to death rites. The Nasser period in Egypt saw primary-student enrolment rise by 234 per cent, and higher education by 325 per cent, between 1954 and 1970.footnote33 For many of these states, education was the path of least resistance for reducing pre-existing class privileges and reordering status hierarchies. It was also a tried-and-tested method of steering citizens to identify with the nation-state’s imagined community more than its competitors.

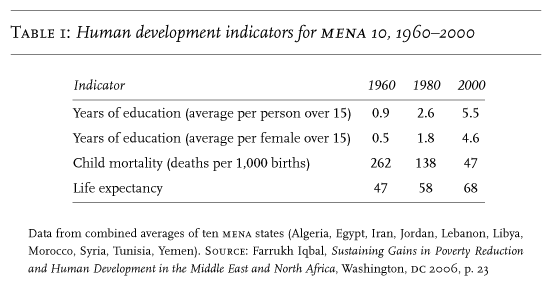

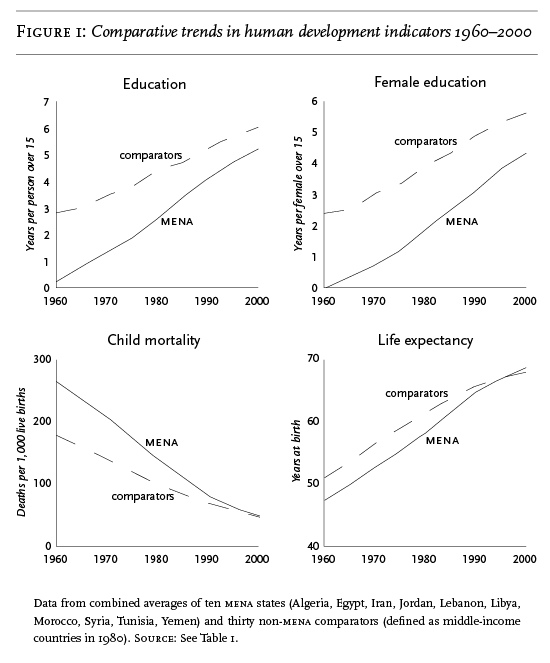

Once in place, the mena state-led social compact had an impressive impact on livelihoods over the next three decades. The World Bank deemed the model as combining ‘rapid growth’ with ‘generous transfers to large parts of the population’. From 1960–85, Arab states outperformed all other Third World regions except East Asia in income growth with equitable income distribution. Infant mortality was cut in half, life expectancy increased by ten years. As far as we can trust internationally comparable poverty lines, mena became a relatively low-poverty region in the global South: 5.6 per cent of the population lived under the $1 a day ppp line in 1990, versus 14.7 per cent in East Asia and 28.8 per cent in Latin America.footnote34 Broadly the same can be said for inequality. Though household surveys in mena tend to measure consumption, not income, Gini levels of inequality in the region floated from around 0.35 to 0.50, well below the extremes faced in Latin America. One survey of Cairo in 1982 calculated the urban Gini at 0.32.footnote35 As shown by non-income development indicators (see Table 1 and Figure 1), a generation of social levelling arguably took place in the post-war era, with positive trends lasting into the subsequent neoliberal period.

As a social compact, however, corporatism contained at least three contradictions which intensified over time. First, a sharp urban bias sat at its core. Even where living standards rose in the countryside as a result of land reforms, rural migrants flocked to cities in search of higher wages in the form of cash income. With the rise in population due to investments in public health, urban bias led to a relative depeasantization of the region.footnote36 The increasing mass of sub-proletarian life in urban areas was impossible to absorb into the state and semi-state apparatus, much less govern in a systematic manner. The response by mena states was to implement systems of subsidies and price ceilings for staple goods and fuel. Inefficient in structure, regressive in absolute terms of total distribution, but progressive in terms of household-consumption effects, subsidies comprised the only universal social policy in the Middle East other than primary education. They were blunt but effective forms of social protection; an understandable approach by states that did not possess the capacity to make their populations ‘legible’ enough to target with anti-poverty programmes.footnote37 After a generation, low prices for commodities became understood as citizenship rights, not state privileges. As population and urbanization increased, the relative weight of subsidies in state budgets rose too.footnote38 Here lay the social setting for the ‘imf riots’ in Egypt and Tunisia of the late 1970s and early 1980s, when these states attempted, and then balked at, raising prices on subsidized goods. From the 1980s most mena states would also open up the countryside to capitalist agriculture, which pushed another generation into the cities.footnote39

Second, staple subsidies and import-substitution industrialization put increasing pressure on mena states’ balance of payments. There was no single source of stable foreign exchange with which to buy capital goods from wealthy countries: migration remittances, oil-money transfers and agrarian surpluses were all too volatile and dependent on cyclical fluctuations in the world economy. The easy phases of manufacturing, from textiles to consumer goods to auto-assembly, had pushed up against the demand limits of domestic markets. The opec price hikes of the 1970s could have, hypothetically, produced the capital to fund a region-wide diversified industrialization strategy. That capital, however, largely ended up in the hands of financiers in London and New York, with Beirut as a secondary beneficiary due to its regional entrepôt function.

Third, even with the exclusionary form of corporatism practiced by mena states, wherein entry to formal-sector employment was limited, middle-stratum beneficiaries began to protest. Often driven by the upwardly mobile and state-employed, such unrest should not be surprising in the era surrounding 1968, when wildcat strikes of formal workers and street protests of university students were commonplace in Europe. If the corporatist social compact was limited on the outside by the extent of public-sector expansion, it was limited on the inside by the empowerment of middle-stratum workers and professionals demanding the democratization of that compact. This resulted in a regional wave of what Robert Bianchi called ‘unruly corporatism’: in countries where ‘authoritarian elites have attempted to force associational life into a tighter state-corporatist mould, their regimes have been deeply shaken or overturned by unanticipatedly powerful oppositions’.footnote40 From Iran to Egypt to Syria to Algeria, these oppositions took secular and religious forms—or sometimes an amalgam of the two—but they all shared similar social bases. In short, mena corporatism produced its own gravediggers through twin processes of proletarianization and professionalization. Hardly the stabilizing ‘authoritarian bargain’ pronounced by Western analysts, by the late 1970s the social compact was being reassessed by elites and masses across the region.

What of the smaller oil-producing states and city-states—were they exempt from the above dynamics? Though Saudi Arabia had won its independence in the 1930s, littoral Gulf states such as the United Arab Emirates or Qatar had only come into formal sovereignty by the 1970s. In most of these territories, an oligarchy of mercantile chiefdoms had long been the ruling elite, with migrant labour utilized in the pearling and portage industries. British patronage and preference led to the rise of selected families as state rulers by the late 1930s.footnote41 Yet, unlike West Asia and North Africa, the Arabian Peninsula was penetrated earlier by us corporate capital, though limited to select sites. In Saudi Arabia, labour regulation was borrowed not from Turkey’s Kemalist model, but from the racialized model of the United States. As Robert Vitalis has detailed, us firms such as aramco exported labour practices from American mining and oil sectors to the Gulf oilfields, with hierarchical tiers of pay and benefits for ‘white’ vs. ‘non-white’ labour. The same practices occurred in uk-established oil-company towns in southern Iran and Iraq, but in those areas nationalization put an end to racial stratification of labour. Not so in the Arabian peninsula, where state-led development codified a tiered racial citizenship in key zones of production well into the 1960s, underpinned by a hard gender division of labour. As the Gulf increased in political and economic relevance during the late twentieth century, this citizenship regime spread as a peninsular model.footnote42 These states’ legitimacy rested on a combination of invented tradition and spectacular forms of outwardly displayed modernization. Kinship lineages became vital for bounded citizenship and informal networks of capital accumulation, which spilled over into large Arab states in the 1970s. The Gulf sheikdoms are not tribal throwbacks by any means, but a sub-category of semi-peripheral state formation.footnote43

A distinction should be borne in mind between mena and other capitalist world regions for the postwar period. Compared to East Asia or Latin America, mena economies remained relatively isolated from outward-going capitalist investment from the core zones of the world economy. The ‘new international division of labour’ that scholars began to notice by the 1970s strikingly did not feature mena territories much at all. Due to a rapid expansion of state capacity, the absorption of newly mobilized subaltern strata into state-corporate bodies and relative economic autarky, mena states built large public sectors to address the pressing social questions of the postwar decades. Industrial growth in the mena region was thus temporarily high, but qualitatively different from Latin American or East Asian industrialization.

States with more limited capacity, such as Lebanon or the Gulf monarchies, succeeded in forging outward linkages from within this autarkic order. These were the entrepôts which presented their territories as windows to Western sources and sinks of capital. The rise of Gulf city-states must be understood in this light, especially after the Lebanese civil war from 1975 and the Iran–Iraq war from 1980. They were zones of relative political stability for capital to reside in and flow through, inviting formal us military power as a buffer in due course. Yet the ‘big push’ of most states in the Middle East, with subsequent effects on livelihoods and social development, should partly be attributed to the relative lack of integration with the capitalist world-economy. By the 1960s, the us preferred indirect geopolitical rule in the region, which remained the case until the 1979 Iranian Revolution. This had parallels with the nineteenth century. Just as the spread of plantation agriculture in the era of British hegemony largely bypassed the Ottoman and Persian imperial zones, with the exception of the Nile Delta and Algeria, so the spread of vertically integrated corporations and their lower-waged subcontractor chains also bypassed the mena region in the era of American hegemony.footnote44 In the climate of nationalist developmentalism, however, this distinction between mena and other world regions was harder to perceive.

By the late 1970s, then, the social compact in most mena states appeared similar, irrespective of ideological persuasion. Its outlines were a relatively large public sector with corporate linkages to various subaltern groups, an expansion of primary health and education to most of the population, a subsidization of staple goods and services for urban classes, and a piecemeal land reform tailored towards strategies of import-substitution industrial growth. Each of these segments underwent partial liberalization from the 1980s onwards. In Arab states, the overall approach was labelled infitah: openness.

4. infitah years

Asserting that the Middle East’s main dilemma is neoliberalism—that this was the cause of the 2011 Arab uprisings, for instance—tells us little about the key dynamics of recent decades. From the 1970s onwards, the mena region was not subject to external or internal pressures of neoliberalization to the same extent as most of Sub-Saharan Africa or Latin America. What occurred during the latter decades of the twentieth century can more aptly be described as a linked divergence inside the mena region itself. Arab states did not actively dismantle their welfare systems so much as let them ossify. Non-state entities moved into these widening gaps of service provision. Turkey and Iran expanded their social compacts due to intra-elite factional politics and continued reliance on popular mobilization. Gulf monarchies, lastly, cordoned off access to social citizenship while actively regulating flows of disposable migrant labour.

Two factors help explain why the region was less subject to the dictates of the neoliberal wave of the 1970s–2000s. First, after the Sino-us détente and denouement of the Vietnam War, the main theatre of military build-up, geopolitical conflict, and mass warfare shifted from East Asia to the mena region. For most mena political elites, and no matter the side of the conflict, war and war preparation served as a useful excuse to fight off technocratic efforts to shrink the state’s budget and privatize national ‘mother’ industries. When state elites did eventually engage in such activities, they did so dragging their feet, a half-hearted neoliberalism at best.

Second, even though many mena states were not oil producers, the commodity bubbles of the 1970s generated sufficient intra-regional transfers of capital to let them keep segments of their corporatist-welfare systems in place. These capital flows, coupled with new sources of external finance for mena states, prevented the deep balance-of-payments crises that Africa and Latin America experienced in the 1980s and 90s, and allowed for the continued use of the public sector as a provider of employment and status attainment. Jordan’s public sector employed more people in the 2000s than in the 1980s. Egypt’s public-sector salaries had risen, not fallen, over the same period.footnote45 To this must be added us flows of military and development aid, which buffered political elites in us-friendly states such as Egypt and Jordan, and were maintained regardless of the numbers held in the regime’s torture cells.

Neoliberal elites abound in the Middle East, well received among the chattering classes of Northern countries. Yet arguably they have never held the reins of power for a long period anywhere but Turkey, and there were no crises deep enough to allow the takeover of Arab states and purging of old guards until the 2011 protests. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, it did seem that limited democratization-cum-liberalization might take hold in the Middle East, as in the rest of the global South, with political councils established in Jordan and Kuwait and regular elections in Iran and Turkey. Yet this proved transient, for the Arab cases, at least, where neoliberal upstarts were selectively grafted into the state by political veterans, from Egypt to Syria, without radical changes to governance. This contrasts again with the Latin American trajectory, where the overthrow of military regimes coincided with the quick application of the technocratic blade to economic and social policy from the 1980s onwards.

Given that the association of many of these states with a hazy secular-left discourse was embedded in the popular imagination, Islamist movements could more easily take advantage of oppositional politics as disillusionment with eroding social compacts mounted. The main beneficiaries of the post-war mena social compact were the middle urban strata, created by and linked to state-led development. As countries began to experiment with reluctant liberalization, cleavages within these middling groups appeared. Political Islam in most Arab states was a phenomenon with middle-class roots, often articulated through university and professional associations. Rarely linked with the seminary traditions of teaching jurisprudence, political Islam largely originated outside of existing religious institutions. From Ali Shariati in Iran to Sayyid Qutb in Egypt, lay people who had amassed prestige in other social spheres also laid claim to the application of spiritual knowledge in regard to social and political reform. Though traceable back to the late nineteenth century, political Islam in the late twentieth possessed divisions homologous with its radical-secular cousins. There were Leninist-type institutions, vertically organized and seniority-based, the most successful (and exportable) being Egypt’s Muslim Brothers.footnote46 There were also more anarchic, cellular organizations, often revolving around a charismatic spiritual guide, which appeared from mid-century onwards.

Arab states’ relations with these Islamists were instrumental at best, often seeing them as a tool to harass or compete with the left. When the 1979 Iranian revolution produced an Islam-garbed state to replace a crucial ally of the us, political Islam was lifted by a wave of prestige among many who knew little about Iran or Shi’a Islam at all. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan produced another ‘international’ of Islamists whose varying ideological persuasions collectively cascaded towards a Saudi-supported salafism. These two waves of rebellion sometimes flowed in tandem, but occasionally crashed into each other.footnote47 Yet the main driver of Islamist success was discontent with the status quo and existing alternatives, given the failed communist rebellions in the mena region. As an amorphous framework which could equally glom onto Third International Marxism, Third Worldist nationalism or high-street banking, political Islam had the added benefit of providing a common touchstone to the nativist promise of a region-wide renewal.footnote48

These intellectual streams circulated while Arab states slowly peeled away layers of the public sector. The initial Egyptian infitah reforms under Anwar Sadat were designed to create a nascent private sector to fill the space left by a retreating state, partly funded by Gulf state investment. Formal liberalization efforts largely ended after Egypt’s 1977 bread riots and Sadat’s 1981 assassination, however. Syria attempted the same under Hafez al-Assad from the 1970s into the 1990s, alleviating foreign exchange constraints and formalizing the networks of private smuggling already taking place.footnote49 Instead of applying shock therapy, Arab governments shuffled off state sectors and agrarian holdings in fits and starts. The result was a long decline in public investment with no concurrent uptick in private investment. Since 1985, the ratio of fixed investment to gdp in mena states has remained between 20–25 per cent. East and South Asian investment rates matched and then surpassed the mena region in the 1980s and 2000s, respectively.footnote50

The opec ‘revolution’ that washed Gulf states in capital did not produce a deluge of investment flowing into populous mena countries. Under a different geopolitical order, perhaps, after the 1967 and 1973 Arab-Israeli wars, these incoming revenues could have been converted into the regional equivalent of a Marshall Plan. The real sink of Gulf capital was, however, Euro-us financial markets, part of which then flowed back to Third World countries in the form of Wall Street private lending.footnote51 The Gulf capital that did travel to mena states was targeted towards activities which barely distinguished it from Western capital—namely, finance and real estate—thus evading state clutches and making it harder to repurpose for state-defined developmental goals. The form of business enterprise attached to Gulf capitalism, the diversified conglomerate, was often portrayed as a monarchical atavism. This trope hid the fact that family-run holding companies and state-linked conglomerates were the most common form of capital accumulation across the global South, globally thriving in neoliberal habitats.footnote52 Gulf companies and their Turkish counterparts expanded into regional markets, competing or collaborating with these countries’ own state-linked conglomerates. While mena economists bemoaned the lack of an ‘autonomous’ private sector, mena businessmen realized profits from the protracted transfer of public goods to the grey zones enabled by private subcontracting and joint-ownership with the state.

Amidst the din, the hidden success story of Arab mena states during the global neoliberal turn was a marked continuation in improvement of non-income welfare levels, at a pace commensurate with the post-war statist period. This occurred while, relative to wealthy Northern states, per capita income levels stagnated and then declined. Between 1985 and 2000, the World Bank reported, mena ‘developing’ countries outperformed other middle-income regions in the global South in their improvement of schooling years, literacy levels, child mortality and life expectancy. This was ‘despite a considerably slower rate of output growth and a decline in levels of public spending’, to the Bank’s puzzlement.footnote53 In fact, compared to countries at similar income levels, mena states performed far worse in terms of income growth from 1980–2000, but their non-income welfare indicators caught up with comparators (shown above in Figure 1 and Table 1).

It is indeed puzzling, and the development literature on the region contains no consensus to account for the data. The convergence of mena with other regions on non-income welfare indicators is observed even when controlling for levels of income and public spending.footnote54 A provisional explanation is that the differentia specifica of the region for its non-income basic welfare successes was the absence of full throttled neoliberalism. An ossifying yet intact public sector was arguably better than one subject to neoliberal strictures. In a weak state, such as Lebanon, private spending on health and education was the norm even in the postwar years. Yet in those Arab states with a legacy of large public sectors, private spending did not serve as a replacement for public services. Given the deepening under-investment in the state, however, two glaring fissures appeared. The quality of service suffered, leading to increased private welfare spending on top of existing social provisions. Also, access to advanced healthcare, as in most countries, was limited to those with social insurance—mainly public-sector workers and the wealthier elite. The welfare institutions of the previous era were never upgraded or expanded.footnote55

For Iran and Turkey, a breakdown in postwar elite rule—by 1979 revolution or by 1980 coup—resulted in a process of unstable intra-elite competition. For all the well-known differences between the two countries, one common fact stands out. This elite competition allowed for newly mobilized social groups to force demands onto the state. Turkey’s ak Party was the most successful actor of them all, wielding a long-curated popular mobilization to eventually transform the political structures of the Kemalist republic. In the process, the uneven corporatist pillars of the welfare system were remoulded into a broader—though perhaps more fragile—social-protection regime that mixed market, state and non-state actors.footnote56 In Iran, continual jockeying within a fractious post-revolutionary elite resulted in the proliferation of new welfare organizations and inclusionary social provisions. Yet the inability of the state subsequently to enforce such regulations has produced a mixed welfare regime, where casualization occurs alongside expanding social-insurance protection.footnote57 Nevertheless, in both cases there has been a marked change in social-protection systems over the past decade, as new segments of the population have been provided access to state welfare.

5. a time of monsters

Given the positive trends mentioned above, why did the 2011 Arab uprisings occur? For one, improvements in non-welfare indicators are not incommensurate with political unrest. Indeed, coupled with lack of income convergence with the wealthy North, especially in light of the rapid economic growth in other Southern regions, grievances were plenty. Given increases in health and education, and a concurrent demographic transition towards nuclear household sizes, exit and voice were prevalent strategies among those who felt blocked from pathways of upward mobility available to previous mena generations. A common option was, as always, migration. Yet mena migration to Southern Europe and the Gulf increasingly came under harsh constraints—‘Fortress Europe’ in the former, a switch to South Asian labour in the latter. Precarity for migrants became the norm, leading to increased internal migration in search of work: Syrians working in Lebanon and North Africans moving seasonally to the Gulf. The classic political safety valve of migration was, for these countries, increasingly obstructed as Northern economies contracted after 2008.

Some of the social grievances highlighted in the 2011 Arab uprisings, however, stem from problems that arose from earlier successes. Mass primary education and basic healthcare were pro-poor interventions by the state. From 1975–2010, Arab mena states enjoyed the fastest rate of growth in average years of schooling for any region. Fertility rates declined and spending per child increased in households. As a result, the subsequent generation’s educational horizons were starkly different from those of their parents. Yet on the tertiary level and in the labour market, class inequality was reproduced. Quantitative gains in educational attainment masked the qualitative avenues of elite status distinction, which reduced the returns on so-called ‘human capital’.

Deeper structural factors were also at play. The baby boom of the 1970s and 80s meant that the number of youth entering working age circa 2010 was four to six times that of those reaching retirement age. The ossification of public investment channelled the search for employment towards private forms, usually informal. Reservation wages tended to be higher than in other Southern countries, with little incentive for foreign capital to hire skilled or technical labour.footnote58 These particulars underlay the relatively high formal unemployment rates for youth in the region, when compared to other Southern countries.footnote59 As a result, many young individuals faced a ‘failure to launch’, as recounted in Tunisia (specifically, the town where the Arab uprisings began in December 2010):

Strolling through Sidi Bouzid’s small downtown area, even on a weekday morning, one inevitably finds the cafés packed with card-playing young men—the streets are filled with outdoor tables, with nary a spare seat in sight. While the youths who sit at the tables often wear superficial smiles, their eyes exude a wistful sadness. Many of these men once had promising futures—some hold university degrees and years ago envisioned themselves in successful professional careers at this point in their lives. Now their only solace is their ability to refer to themselves as lawyers or engineers; despite never having worked in these fields, the formal titles that their generally useless certifications carry confer at least a sliver of dignity.footnote60

This social stratum is awkward to classify in theoretical terms. Carrie Wickham has labelled such individuals in Egypt as the lumpen intelligentsia, a ‘professional underclass’ with ‘graduates unable to find permanent white-collar employment’—‘not unemployed so much as forced to accept jobs they perceived as beneath the dignity of someone with a university degree’.footnote61 While the 2011 uprisings had roots in earlier formal labour protests, this new stratum was present throughout the initial protest wave across the region.footnote62

Fortunately, on account of questions added to the 2011 Arab Barometer Survey in Tunisia and Egypt, survey data exist which detail some of the contours of unrest in these two cases. Protest participants in both countries tended to be mostly male, with above-average income and education levels. Some 46 per cent of surveyed protestors in Egypt, for instance, had at least some university education, compared to 19 per cent of the population as a whole. Unemployment was not a predictor of protest, nor was youth, but protestors disproportionately possessed professional and skilled vocational backgrounds compared to the rest of the population. More unskilled workers protested in Tunisia than in Egypt, the surveys found, but in both cases there was a disproportionately high rate of protest participation by government employees. Women who participated tended to be active in the labour market. The younger the age of the protestor, the more likely he or she was to identify economic grievances or corruption, rather than civil and political freedoms, as the key motivation for participation.footnote63 Snapshot surveys cannot capture questions of timing and process in the two countries’ uprisings, but they do give some weight to the lumpen intelligentsia’s role as compared to the formalized proletariat or informal sub-proletariat. It is also not surprising that such middle-stratum individuals are over-represented among domestic and transnational political Islamists of various stripes.footnote64 Some of their energetic activity goes towards establishing non-state charities, clinics and schools. Arab states usually preferred such energy to go into charity rather than politics. As it grew in relative size and scope, the religious-aid sector in mena Arab states dovetailed with the rise of a neoliberal discourse about promoting ‘good governance’ and ‘human capital’. On the one hand, this tended to add legitimacy to particular Islamist parties which, never having been in office, nevertheless benefited from the reputational esteem associated with technocratic know-how.footnote65 On the other, the embourgeoisement of political Islam did not assuage the cleavages among political and economic elites in Arab states. In fact, given the rapid expansion of a pious yet subordinate intelligentsia in many countries, intra-elite competition and polarization was to be expected.

As a sop to the poorest strata, mena Arab states did not fully liberalize their subsidies on staple goods and fuel. The increasing trend, in line with other regions, has been to replace segments of the subsidy system with new ‘targeted’ anti-poverty programmes. Unlike in Latin America, these are relatively new, small-scale and disconnected from party mobilization. Along with decreased spending on public housing and infrastructure, the erosion of the previously established social compact has contributed to the informalization and casualization of the domestic labour force, including disguised female labour.

If there is an overriding factor determining the trajectory of mena states, however, it is not neoliberalism so much as militarism. While sporadic wars took place in the region after 1948, since the 1970s there has been a long cascading war with multiple sub-currents. At least three varieties can be distinguished. First are national-expansionist projects under us protection—Israel in Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, the Sinai; Iraq into Iran; Saudis in Yemen; Iranian soft expansionism in Afghanistan and Iraq. Second are national-expansionist projects without us protection—Iraq into Kuwait, and all that entailed. Third, conflicts with a popular-war dynamic, where social discontent has combined with national anger—Palestinian intifadas, Yemeni oppositions, Hezbollah, the pkk, Sunni militias in Iraq—which often become entangled with internal security struggles and temporary external alliances. The exception of Tunisia looms over the rest—a military reluctant to exercise power and an Islamist party, Ennahda, willing to cede it. This semi-permanent state of war and increasingly direct intervention by us-led forces set the stage for a series of counter-revolutions after 2011 to contain or, in Libya and Syria, militarize the wave of mass uprisings.

The other outcome of this war cascade was to push the political and economic leadership of mena states towards the Gulf monarchies. The Gulf model attempted to create a costless, codified capitalism: social citizenship for elite kinship minorities, imported professional and working classes, and territorial security subcontracted to the American superpower. Celebrated by sycophants and held up as an obverse to state-led development, the model is under strain on all three fronts. Young Gulf Arabs are growing tired of being cloistered and pampered without career trajectories, leading the monarchies to pursue a half-hearted policy of ‘nationalization’ of the workforce, with increased costs in tow. The long-term circulation of South Asian and North African labour throughout the Gulf has built up local communities with their own resources of social solidarity. Hidden resistance is still the norm, but the costs of containing labour unrest are growing. The us protection umbrella, as royals now grumble, is looking more like a protection racket. But if the Gulf monarchies had to protect themselves, they would also have to enter into a more ordinary balance of power in the region where Iran, Turkey and other possible competitors could claim a veto, irrespective of us or Israeli wishes. This has occurred to some extent anyway, making the Gulf model even more precarious.

Like the 1848 revolutions, the 2011 uprisings brought forth a reactionary wave of violent containment. Why have tyrannical regime forms, monarchies or republics, maintained such a vice-like grip on this region, when elsewhere the dictatorship model has largely been relegated to the lumber-room? If modernizing states had initially consolidated themselves against oligarchic landowners, they hardened further as the corporatist social compact came under strain from the 1980s and 90s, with the explosive growth of unabsorbable urban populations and the long decline in productive investment. But over-determining this has been the designation of the region’s heartlands as the world’s major war zone. The scale of the conflicts there have escalated from 1990, when the disappearance of the ussr as a countervailing force lifted restraints on us deployment of firepower as a continuation of politics by other means, with the aim of maintaining its prerogative over the world’s largest oil reserves and protecting Israel. The upshot has been not only to fuel opposition, in the form of political Islam, but to strengthen us-friendly elites with billions in military aid. Where Muslim Brotherhood parties were offered the chance to provide an Erdoğan-style alternative, as in Egypt and Tunisia, they proved too parochial or debilitated to seize the day. Only in Iran has Washington succeeded in extracting a political agreement with popular-democratic support. Across the region, the Western response remains as uneven as ever: a full-dress, un-sponsored air war on Gaddafi; a blind eye to Saudi and Emirati repression in Bahrain; endorsement of Saudi blockading and bombardment of Yemen; covert orchestration of Gulf-funded arms flows against Assad in Syria, combined with sporadic aerial devastation of isis strongholds and renewed micro-management in Iraq.

If authoritarian retrenchment were the sole outcome, the situation would be less dire. In the decade and a half since the us invasion of Iraq, segments of the postwar mena political order have shifted back towards the politics of notables, local social formations and transnational flows of pamphlets, labourers and revolutionaries. In the previous iteration of the early twentieth century, it took waves of anti-elite, anti-colonial mobilizations, as well as radical political state-building projects, to produce order from the mayhem. For the time being, however, the chances of a repeat look rather slim. Instead, as occurred in Afghanistan during the 1980s and 90s, coherent and crafted political systems along the Maghreb and Levant are being pulverized into a set of rump chieftaincies. The labour reserves that had been accumulating during the shrinking of the state—unskilled proletarians and skilled professionals alike—are now the uprooted migrants sitting in the shatter zones of the old geopolitical order. As reported in the lrb, ‘The mobilization techniques used in the Arab Spring, which brought thousands of demonstrators to a given place, were now being used to organize the new waves of migration’.footnote66 Increases in health and educational attainment produced in post-war social compacts are being reversed for a generation. It remains to be seen if stand-out regional powers can prevent their own further entanglement. More likely, as with the Saudis in Yemen or the Iranians and Turks in Syria, powers left standing will mistakenly equate long reach offensives with renewed stability in their own shaky domestic orders.

If some form of cold peace comes to the region after further population resettlement, new social questions for the mena might revolve around centres of state power and capital accumulation, their exploited peripheries of inclusion and their excluded remainders. Competitive spheres of influence are not necessarily anti-developmental, if order is established and new cadres are developed. Yet even if geopolitical conditions were to improve, stability would require states to build political and social compacts that not only incorporate wider segments of the population but also significantly reshape their life chances. It is unlikely, though, that emulating the developmental models of the present will create a solid compact for mena states. Processes of urbanization and depeasantization that were corollaries of mena state formation meant that the rural reserves of semi-proletarian labour that fuelled rapid growth in East Asian markets and lured in Western capital are today nowhere to be found. The rural subsidization of social reproduction cannot be re-created. As Faruk Tabak has pointed out, access to plantation labour attracted Western capital flows in the late nineteenth century, while access to rural networks of semi-proletarian labour in East Asia supported the manufacturing activities in which global capital invested in the late twentieth. The Ottoman Empire lacked the former, and today the Middle East lacks the latter.footnote67 Its remaking is beyond current horizons.