The outcome of the 1977 general election represents a watershed in the history of modern Indian politics. For four whole days the Indian electors—almost 200 million men and women—flocked to the polling booths in town and countryside. Deprived by the Emergency of virtually all forms of extra-parliamentary dissent such as strikes, street demonstrations or distribution of oppositional literature, the Indian masses utilized the ballot box to express their deep discontent. The result was a veritable political earthquake which shook India and whose tremors were felt in the remotest regions of neighbouring Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Its impact in the realm of world politics was also considerable: it produced gloom and despondency in Moscow; ill-suppressed, albeit shortsighted, jubilation in Washington; while in Peking it was greeted as a ‘blow against social-imperialism’. The choice which confronted the Indian masses was not a complex one. The election was about the Emergency. As such it was more of a referendum than an election. As Congress rule was identified with Emergency rule, and as it was portraits and photographs of Indira Gandhi which adorned every locality rather

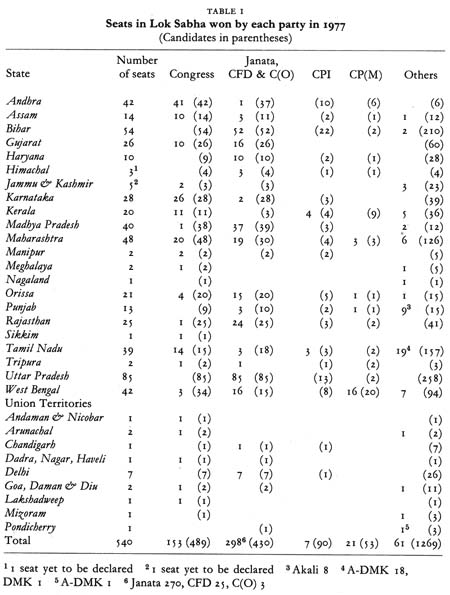

The total number entitled to vote was 320 million, which made it the largest bourgeois-democratic election in the world. The percentage that voted was 60·54 per cent, the highest except for 1967, when 61·33 per cent went to the polls. In absolute terms, it was the highest recorded vote in the history of India. It was the most decisive election as well, in the sense that it saw the displacement of the Indian Congress Party as the major ruling-class party of the country. A political tradition established in 1937 finally crumbled four decades later. The northern and central strongholds of Congress were captured by the opposition coalition—Janata Party—one after the other. Of forty-nine central ministers contesting the election, only fifteen were successful. In the largest state (in terms of seats)—Uttar Pradesh—the Congress was unable to win a single seat. Moreover, in the process a truly historic precedent was established: Indira Gandhi herself was defeated by a maverick oppositionist, Raj Narain, by a margin of 50,000 votes. This is probably the first occasion on which a sitting Prime Minister has been humiliated in this fashion in the entire annals of representative bourgeois democracy. It constitutes a remarkable tribute to the resilience of Indian political institutions, themselves unique in the third world. Indira’s personal defeat (together with that of her son in a neighbouring constituency) marked the lowest point in the history of the Nehru dynasty. Her father, Jawaharlal Nehru, and grandfather, Motilal Nehru, had always remained popular in the city of Allahabad.

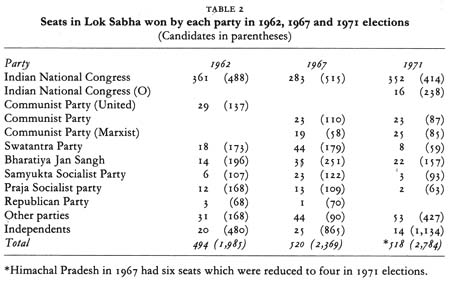

In addition to Congress, the other main loser was the Communist Party of India (cpi), its shame-faced and pusillanimous ally. The last-minute decision by the party’s high command to distance itself from the Congress made no impression on the masses. From twenty-three seats (gained and maintained in the two preceding elections of 1967 and 1971), the cpi slumped ignominiously to a grand total of seven seats, confined to the southern states of Kerala and Tamil Nadu. In West Begal, the party was totally obliterated and its best-known leaders Indrajit Gupta and Hiren Mukherji removed from the central arena of national politics. Its rival Communist Party of India (Marxist)—cp(m)—essentially retained its strength. It lost only two seats, though these were in Kerala, one of its two former strongholds.footnote1 All but six of its seats were won in the important and populous border province of West Bengal.

The total vote gained by the Congress was 35·54 per cent, and but for its gains in the south its defeat would have been complete. The new political boundaries of India thus reflect a north-south division. While it is extremely unlikely that this will be a permanent division (Congress’s main ally in Tamil Nadu is already engaged in negotiations with the victors at the centre), it nonetheless does reflect certain political facts and fears. In a more general sense, there are a number of reasons which explain the defeat of the opposition in the four southern states. In two of them, Kerala and Tamil Nadu, Congress was not the traditional ruling party. It had only entered the government in the sixties, and in Tamil Nadu the dmk had been the ruling party with powerful support from the regional bourgeoisie. Even so, it was replaced only by an alliance of the Congress with the a-dmk, a split-off from the dmk. It is this group which is now preparing to abandon the Congress. In Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka there was—and remains—a fear that the Janata bloc might attempt to re-impose Hindi as the national language and ride roughshod over the linguistic and cultural rights of the population. Furthermore, the excesses of the Emergency, fortunately for Congress, were not felt in the south; the Kerala Congress leaders, for example, had firmly refused to allow Sanjay Gandhi to visit their State. The Kerala government—a cpi-Congress united front—was also reputed to be less corrupt than other state governments, and had succeeded in implementing a series of land reforms in the state.footnote2

The victorious Janata Party was itself a heteroclite cartel dominated by right-wing parties. At its head was the figure of J. P. Narayan, a veteran nationalist politician who symbolized in the eyes of the masses all opposition to the Emergency. For while it was revulsion against the Emergency that lost the Congress the elections, it was also important that the Janata Party was able to project itself as a coherent ruling-class alternative. Its policy statements were extremely vague throughout the campaign, the central focus being a ferocious personal assault on Mrs Gandhi, her son and the two most sycophantic members of her political entourage, cabinet ministers Bansi Lal (Defence) and Shukla (Information)—now referred to as the ‘Gang of Four’ by sections of the Indian press. Politically, the demand for unrestricted civil rights and attacks on the forced sterilization campaign made up the entire panoply of the Janata’s campaign. Its startling success is reflected in its capturing 270 seats out of a total of 493 which it contested and gaining 43·17 per cent of the popular vote. This gives it half the seats in the new parliament, and together with the seats won by the Congress for Democracy (cfd) of Jagjivan Ram and the cp(m), which has now amalgamated with it, the new government has a comfortable position in electoral terms.

The major victor in real terms has been the right-wing, communalist Jana Sangh party. Its organizational dominance of the Janata coalition has paid off handsome dividends. Since all individual components of the Janata have formally dissolved their respective political parties, it is not possible to compute the exact number of hard-core Jana Sangh members in the new parliament, but they are reported to have well over a hundred deputies in contrast to twenty-two in the outgoing legislature. This advance is sufficiently significant for us to pay some attention to the Jana Sangh’s antecedents.