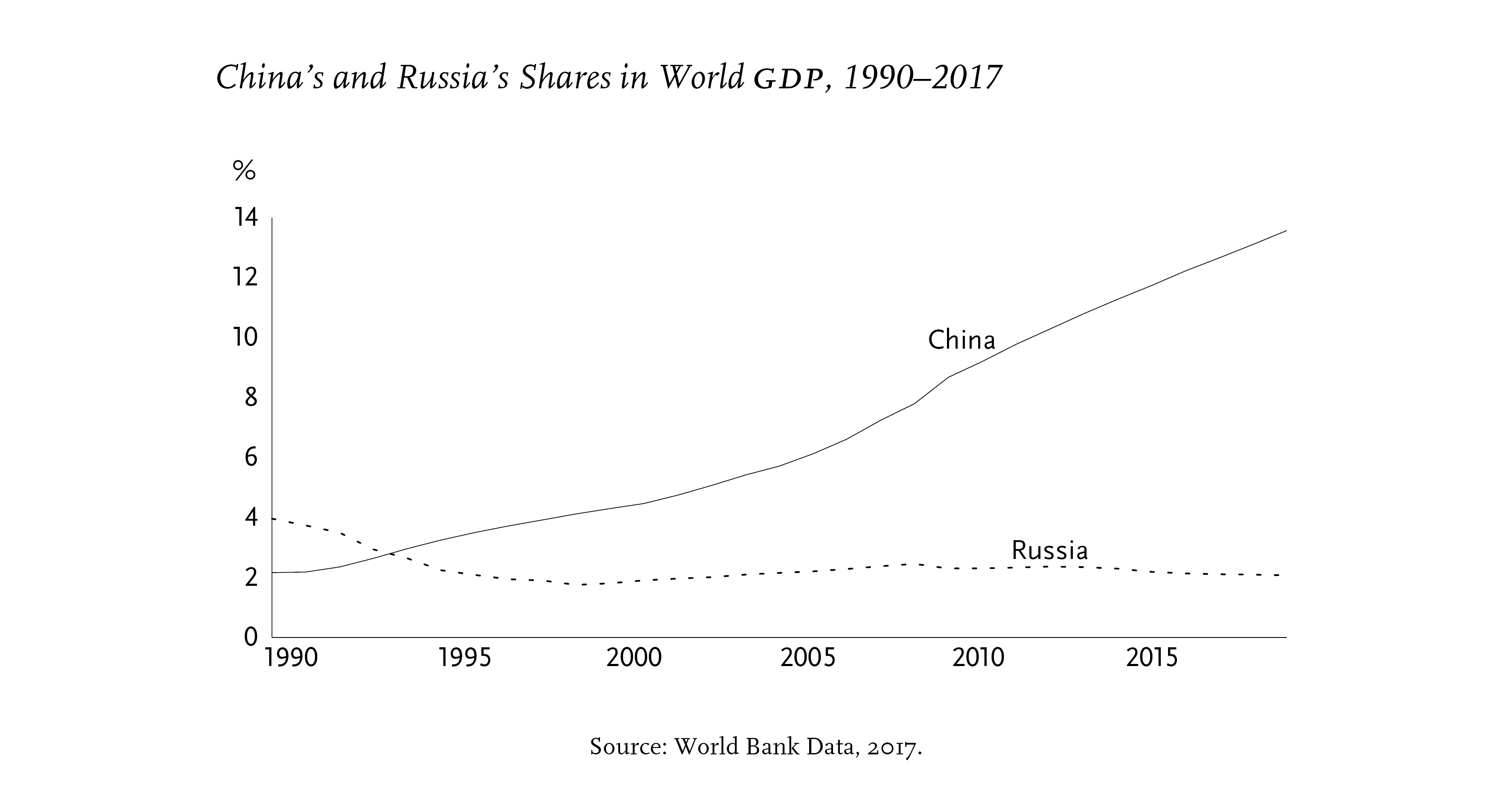

To illustrate the stakes of market-reform debates in China in the 1980s, Isabella Weber begins her book with some dramatic graphs. The first (below) compares Russian and Chinese shares of world gdp between 1990 and 2017. It shows that Russia’s proportion halved in this period, whereas China’s grew nearly seven-fold.

This dramatic divergence, Weber argues, was a consequence of the shock-therapy policies carried out in Russia after 1991, starting with the wholesale liberalization of prices. As prescribed by neoliberal economists, the goal was to make the transition from state-socialist to capitalist economy as rapidly as possible. In this view, gradual market reforms would simply lead to backsliding. The only guarantee of success was to eliminate price controls and social subsidies in one fell swoop—to compel existing enterprises to survive in a harshly competitive environment, eliminate old practices and clean out dead wood, preparing the ground for sounder, market-based development. Russia followed this path and saw its economy collapse. Since then, its growth has been uneven, but generally slow. China, however, resisted the prescription and has done much better. The prc is deeply integrated into global capitalism, yet Weber argues, it has not undergone ‘wholesale assimilation’ or ‘full-fledged institutional convergence’ with neoliberal norms. This tension between China’s rise and its only ‘partial assimilation’ defines our present moment, she writes. The purpose of How China Escaped Shock Therapy is to explain this divergence, which Weber does very well.

Drawing on her interviews with many of the policy intellectuals involved, Weber shows how close Beijing came to adopting shock therapy in the 1980s. Enticed by the confident theories of leading Western neoliberal thinkers—and reassured by émigré Central European economists like János Kornai, Włodzimierz Brus and Ota Šik, who led reform attempts in Hungary, Poland and Czechoslovakia before fleeing to the West—Chinese leaders actually took the first steps, before pulling back in the face of severe social and political reactions. They were saved, Weber argues, by the ccp’s long tradition of pragmatism. To borrow the metaphor made famous by Deng Xiaoping, they waded boldly out into the river, felt the pull of its fast, deep currents and stepped back just in time, to take a different path. This is not a new story, but Weber’s research provides fresh and compelling insights into the experience and world outlooks of the participants in the fiercely fought economic debates of the 1980s. Born in the frg just two years before the fall of the Wall, Weber studied in Berlin and at Peking University, going on to read economics at the New School and to take her PhD at Cambridge with Peter Nolan. She now teaches economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and is Research Leader in China Studies at its storied Political Economy Research Institute. Her investigation draws upon insights from many different angles in the discussion over China’s economic reforms—grizzled ccp cadre, young liberal-minded economists, sent-down students, World Bank officials, émigré free marketeers. By any measure, this is an impressive contribution.

In Weber’s telling, the choices made by the veteran ccp leaders after Mao’s death in 1976 were profoundly informed by their experience in restoring economic activity in the liberated areas during the Civil War—which in turn was shaped by deeply ingrained traditions of Chinese classical thinking about economic statecraft. She delves deep into the Han-era treatises on economic intervention collected in the Guanzi, a major compilation from 26 bc by the polymath scholar Liu Xiang of philosophical, political and scientific writings dating back many centuries before. In her account, the theories of the Guanzi economists sprang from the need to calibrate new state–market relations during the Warring States era, a period of technological advance and inter-state competition. The writers emphasized the importance of public granaries and state intervention to stabilize prices and create ‘equable markets’, buying grain when prices were low and selling when they were high—policies institutionalized under the Han emperor Wu (157–87 bc) by his minister Sang Hongyang, who also revived state monopolies over salt and iron to replenish Wu’s war-depleted treasury. Wealthy merchants and rebel aristocrats were thereby weakened, and their lands confiscated for small farmers to work.

A key concept for the Guanzi economists was the distinction between qing (light) and zhong (heavy). These terms could refer respectively to small and weighty coins, and qingzhong as a compound could mean price intervention; more broadly, it was used for a whole range of economic policies, from state monopolies to work incentives and currency control. Crucially for Weber’s argument, the Guanzi writers distinguished between economic processes and commodities that were ‘heavy’, in the sense of central or important, over which the state should exercise control, and those that were ‘light’: marginal or inconsequential goods and practices, which could be left to the market. Yet these categories might vary according to the surrounding conditions, the locality, the season. The injunction to state officials to ‘grasp what is heavy and let go of what is light’ therefore demanded an inductive, experimental approach, using empirical surveys and data-gathering to ascertain prevailing circumstances and adapt the balance of heavy and light accordingly. After Emperor Wu’s death a major conclave was held, resulting in the famous ‘Salt and Iron Debate’ between the supporters of Sang Hongyang’s interventionist approach and the traditionalist scholar-literati, who aimed to reinstate a vanished golden age of ritual order and dutiful behaviour, in which state regulation would be unnecessary and a laissez-faire approach might prevail (to the benefit of large landowners). These ‘idealist’ literati, Weber reports, typically saw state intervention as a source of corruption and favoured self-regulation through moral conviction; ‘pragmatic’ officials, by contrast, saw state regulation as vital to avoid fluctuating prices and socio-economic chaos. These debates were successively renewed in the millennia that followed; Weber cites in particular the high Qing-era investigations that influenced Mao and the enduring practice of the Ever-Normal Granary, to smooth food prices.

After laying out these legacies, How China Escaped Shock Therapy turns to the policies of the Mao era. Here Weber highlights the tension between proponents of a Soviet-style plan for heavy industrialization and others, including the economic strategist Chen Yun, who stressed the importance of studying on-the-ground conditions and following an inductive approach, developing agriculture and light industry first as a basis from which to industrialize. She argues that the initial measures deployed in the liberated areas in the 1940s—reintegrating war-shattered economies through state cooperatives, indirect price regulation through market intervention—drew in part on Guanzi-style traditions. Chen Yun, charged with financial policy for the northern border regions during the Civil War, prioritized controls over grain and cotton, ‘heavy’ commodities, to help stabilize prices during the hyperinflation. In Shandong, Xue Muqiao took control of the salt tax—a crucial move in establishing a stable fiscal base for the ccp currency, as against that of the kmt. Chen Yun may have been the first to invoke the famous piece of folk wisdom about crossing a river as a guide for ccp economic policy, telling a State Council meeting as early as April 1950 that if rising prices were bad, falling prices could also be deleterious for production, and the money supply should be adjusted accordingly: ‘It is better to be feeling for stones to cross the river more steadily.’

For most of the Mao era, the prevailing approach was instead that of a command economy, Weber argues, although she depicts Mao initially tacking from one side to the other. After welcoming Soviet planners, his 1956 speech, ‘On the Ten Major Relationships’, backed an emphasis on agriculture and light industry, before he switched to the disastrous voluntarism of the Great Leap Forward, followed by the Great Famine. In its wake, Chen Yun was put in charge of the recovery and began to reintroduce rural markets and family-worked plots, proposing his ‘birdcage’ model—the market singing within the encompassing state plan—before being sidelined as a capitalist roader during the Cultural Revolution. By the time Mao died, socialist policies had brought about impressive advances in industrialization, as well as public health and education. Prices were stable, set by the state in a fashion that extracted wealth from the countryside to build industry. But the overall growth of the economy was no more than average for developing countries and living standards remained low, especially in rural areas.

Deng, who took over the reins of state in 1978, was not satisfied with this relatively slow rate of growth and was convinced that introducing markets would speed things up. By the end of the year he had brought Chen Yun onto the Politburo Standing Committee. The ccp announced incentives to revive rural markets and petty private production by introducing a dual-track system for key agricultural products: once the low-price state quota had been fulfilled, peasants could sell any surplus at a higher price. The logic of the dual-track price system—quota and market—drew upon that of the Guanzi treatises, Weber argues, noting the surge in studies of classical Chinese writings on economics that paralleled the reform-era debates. The state would consciously harness market forces, using the principles of ‘heavy’—the necessary grain procurement of the quota, ‘to ensure that people’s livelihood is not affected by a rise in prices’, as Xue Muqiao put it in China’s Socialist Economy (1979), quoted by Weber—and ‘light’: the marketable surplus, acting as a spur to increase productivity.

Driving this emphasis on the rural economy, for Weber, was an unprecedented cross-generational alliance produced by the social upheaval of the Cultural Revolution. In her account, the veterans of the 1940s struggle in the countryside were joined by a cohort forty years their junior: students ‘sent down’ during the Cultural Revolution and returning to the universities after 1978 committed to dismantling rural collective structures. How China Escaped Shock Therapy captures well the extraordinarily open intellectual climate of the time, as the re-opened Chinese Academy of Social Sciences became a seedbed for new ideas, and Weber endorses the approach taken by a particular set of scholars at the Rural Development Research Group and the System Reform Institute, a think-tank close to Zhao Ziyang which housed younger researchers like Chen Yizi and Wang Xiaoqiang, among many others. In Weber’s telling, this coalition of leaders and young scholars, conducting on-the-ground surveys and testing out policies in particular localities, was a crucial factor in the dramatic take-off of the rural economy in the 1980s.

At the same time, Chinese leaders began inviting Western neoclassical economists, Milton Friedman among them, to offer advice, alongside émigré Europeans like Kornai, Šik and Brus, and full-dress delegations from the World Bank. All were dedicated opponents of the cautious dual-track price system, and instead counselled rapid, wholesale price reform—a ‘big bang’, making a decisive break with the past—as the only way to kickstart profit-driven growth. As Brus’s student Anders Åslund put it, ‘The main issue is to cross the river as fast as possible in order to reach the other shore.’ They found ready listeners among a growing group of influential Chinese economists, including Wu Jinglian at the cass Institute for Economics, along with younger scholars like Guo Shuqing, later China’s chief banking regulator, and, by the mid-80s, Xue Muqiao himself. Others, initially including Zhao Ziyang, were less convinced. They worried that such a radical break would be too disruptive and favoured a gradual introduction of market prices, while reforming existing institutions so that they would be able to operate effectively in a marketized environment. They argued for continuing the dual-track price system and expanding it into the industrial sector by means of gradualist experimentation.

Weber dubs these two broad camps ‘idealists’ and ‘pragmatists’ and points out similarities between the lines of divide in the 1980s and those of the Salt and Iron Debate, two millennia before. The real distinction between them, she maintains, was not the pace of reform but its epistemic logic: deductive reasoning as opposed to inductive research. The idealists put their trust in a self-regulating market—replacing the moral regulation of Confucian philosophy—while the pragmatists insisted on maintaining a degree of state regulation. While the big-bang proponents insisted that prices in core industries, which they saw as most distorted, required immediate change, their adversaries preferred to start with ‘light’ sectors and move gradually to ‘heavier’ ones. The former were typically academics, more enamoured of theory, while the latter were more closely connected with policymaking. The heroes of Weber’s story are the pragmatist economists and party officials who resisted the prescriptions of neoclassical orthodoxy and thus avoided the catastrophic consequences of shock therapy.

Members of both camps sought to bolster their arguments with imported knowledge. Adherents of the pragmatist camp, among them Chen Yizi and Wang Xiaoqiang, undertook fact-finding tours in Hungary and Yugoslavia, where officials and establishment economists warned of the destructive consequences of their own short-lived big-bang price reforms in the 1960s and 1970s, which had led them to retreat to a more gradual path. Tellingly, Hans Karl Schneider, an Eucken-trained West German ordoliberal who had worked under Erhard, counselled these Chinese researchers against accepting Friedman’s account of the ‘Erhard miracle’ at face value: Germany had not liberalized coal and steel prices until the 1970s; it would have been disastrous to have done so in the immediate post-war period, when raw materials were in short supply. Meanwhile, proponents of radical price reforms were bolstered by the spectacular Bashan conference, led by World Bank and émigré European economists, and held on board a luxury cruise ship floating down the Yangtze. At the same time, the Europeans hinted that it would probably not be possible to carry out radical price reforms without fundamental political change, a suggestion that would have been most unwelcome to some of their Chinese interlocutors, who, while they embraced the principles of Western neoclassical economics, were firmly embedded in the party establishment.

Both ‘idealists’ and ‘pragmatists’ also looked to Latin America, and both sides were impressed by the pioneering neoliberal programme carried out by Pinochet in Chile, under the tutelage of University of Chicago economists. However, they took different lessons from the Chilean experience, with one side celebrating the success of Pinochet’s sudden elimination of price controls, and the other pointing out that his big-bang approach was predicated on market-adapted businesses. In China, where enterprises depended on price controls, and were not equipped to compete for profits by shedding workers and raising productivity, such a radical move would be too risky. Both camps also sought—and found—the ears of China’s top political leaders. At two critical junctures, Weber recounts, big-bang proponents nearly prevailed. In 1986, Wu Jinglian, Xue Muqiao and others succeeded in winning Zhao Ziyang to their position, but he backed down after running into strong opposition, not least from his own System Reform Institute. In 1987, the ccp leadership committed itself instead to a policy of large-scale coastal development and implementing an enterprise-contracting system—an approach Weber describes as ‘an internationalized version of gradual marketization from the margins and the dual-track price system.’

Yet pressure continued to build for big-bang price reform, in part from an increasingly impatient Deng Xiaoping, but also, Weber argues, in response to popular anger at growing corruption among party officials, profiting from their role as gatekeepers in a semi-marketized system. Liberalizers argued that all-out privatization would do away with profiteering bureaucrats altogether. In 1988, Deng himself took up the banner of radical price reform, and this time central authorities actually took the first steps. The August 1988 Politburo meeting at Beidaihe announced the liberalization of all prices. The immediate result was runaway inflation—soaring from 12 per cent in July 1988 to 28 per cent in April 1989—exacerbated by panic buying and bank runs. Within weeks, the pragmatic Deng backed away. Chen Yun was called in to reverse the liberalization and impose stabilized prices on key goods. China had escaped full-blown shock therapy by a whisker, Weber argues, yet Deng’s aborted 1988 price-reform push came at a high price: its destabilizing effects helped to catalyse the political crisis that culminated in the massacre of June Fourth.

The dual-track heroes of Weber’s story were largely sidelined after Tiananmen. Nevertheless, she argues, the reform approach they helped to shape and defend has survived: ‘The model of gradual, experimentalist marketization remained in place from the 1980s to the present. Although challenged and amended, it was not overturned.’ Despite the fact that neoliberal reforms made deep inroads in terms of private ownership, labour markets and healthcare, ‘the core of the Chinese economic system’ was not destroyed. When prices were liberalized in the 1990s, it came as a ‘small bang’, preserving the central institutions intact. In Weber’s view, the dual-track price system was ‘at the heart of China’s transformation from a poor agricultural country with revolutionary ambitions to one of global capitalism’s manufacturing powerhouses.’ Instead of experiencing severe economic decline and deindustrialization, like Russia, its dual-track reforms ‘laid the foundations for economic ascent’, albeit under tight political control. ‘The state maintained its role over the “commanding heights” of China’s economy as it switched from direct planning to indirect regulation through state participation in the market’, Weber concludes. China ‘grew into global capitalism’ without losing control over its domestic economy.

The detailed analysis of the 1980s market-reform debates offered by How China Escaped Shock Therapy is insightful and illuminating, and Weber’s evidence for the roles played by economists in providing theories and policy suggestions to key party leaders is especially helpful. Her focus on these debates, however, remains relatively narrow. In presenting the System Reform Institute economists Chen Yizi and Wang Xiaoqiang as patriotic pro-peasant reformers, she comes close to the official story about egalitarian-minded Chinese leaders responding to villagers’ demands. (As she acknowledges, by the late 1980s Chen and Wang found much to admire in Pinochet’s Chile.) The reality in the countryside was more complex and politically fraught: certainly many villagers supported decollectivization, but—as Jonathan Unger, Joshua Eisenman and others have demonstrated—many others did not.

By concentrating on clashes between what might be better identified as two wings within a single camp of radical marketizers, she neglects the arguments advanced by the substantial group of party leaders who favoured far more moderate market reforms that would have preserved socialist institutions. She occasionally mentions Chen Yun and Deng Liqun, who became prominent spokespersons for this ‘conservative’ camp, but they enter her narrative only as opponents of big-bang price reforms, rather than proponents of another road. At the same time, although Weber does not say this, the European émigré economists may ultimately have been right to argue that only regime change would make it possible to follow through with shock therapy. In Central Europe, just as in China, as long as Communist parties remained in charge, they ultimately pulled back from the brink. It was only after 1989 that new post-Communist regimes were willing to commit themselves to big-bang policies so fervently that they did not retreat even when their economies began to collapse.

While Weber ends her detailed account at the close of the 1980s, her thesis could well be taken forward to the subsequent decades, as the ccp continued to implement what she calls its Guanzi-style policies after 1988. Although some market reforms were put on hold after the violent repression of the Tiananmen protest in 1989, price reform was accelerated from 1992, followed by enterprise restructuring and privatizations which led to widespread bankruptcies and some 60 million layoffs within the span of a few years. Here Weber would surely have noted that the ccp once again followed the traditional ‘light versus heavy’ model, starting with small and medium enterprises, and only gradually moving on to larger firms, while keeping those considered most essential—finance, energy, telecoms, land—firmly under state control. For although the Chinese industrial-restructuring process that began in the 1990s had many of the hallmarks of the neoliberal reforms sweeping the former socialist bloc at the time—as well as the capitalist world—it is true to say that Beijing’s policies never fully conformed to the neoliberal model. Moreover, after the turbulence of the late 1990s, Chinese leaders began to pull back from their marketizing push in the 2000s, reinforcing the role of the state, a trend that continues today. As How China Escaped Shock Therapy explains, the ‘pragmatic’ mode of mixing state direction with market mechanisms, established in the 1980s, continues to hold sway.

In making her case for pragmatism against idealism, Weber notes that the Chinese economists who were the most ardent proponents of market fundamentalism in the 1980s had often been equally enamoured with comprehensive socialist-planning models in the 1950s. She points out that both visions—of perfectly functioning markets and perfectly functioning plans—are products of the same type of theoretically driven rationalist thinking. She might also have noted that in his time Mao was for the most part an obstinate adversary of such planning fantasies. He was, as she says, an extremely disruptive force, more interested in continuing the revolution than in building permanent institutions, and consistently favouring political mobilization over economic incentives. Yet in the process, he also repeatedly promoted decentralization and local initiative, which—unintentionally but inevitably—fostered exchange outside of the plan.

Adjusting Weber’s framework a bit, we might contrast theoretically driven economists who sought to find perfect economic models—whether based on planning or on self-regulating markets—with political leaders who saw economic policies merely as instruments to accomplish programmatic goals. Mao and Deng both belonged to the latter category, although their programmes were different. Both were intent on developing China’s economy in order to accumulate national wealth and power. But as long as Mao was alive, this project had to share space with radical-collectivist and class-levelling goals. The ccp’s egalitarian and collectivist ethics would not tolerate anyone ‘getting rich first’. When Deng came to power, he emphatically rejected these other goals; the singular project became the accumulation of national wealth and power, and to achieve this he insisted that some would have to be the first to get rich. In terms of the accumulation of national wealth and power, market reform has been a spectacular success in China and a dismal failure in Russia. Because this is the metric of Weber’s comparison, the lesson driven home by her book is that the transition from socialism to capitalism does not have any foregone conclusion; in terms of economic growth, How China Escaped Shock Therapy implies that success or failure depends on the strategies that leaders employ.

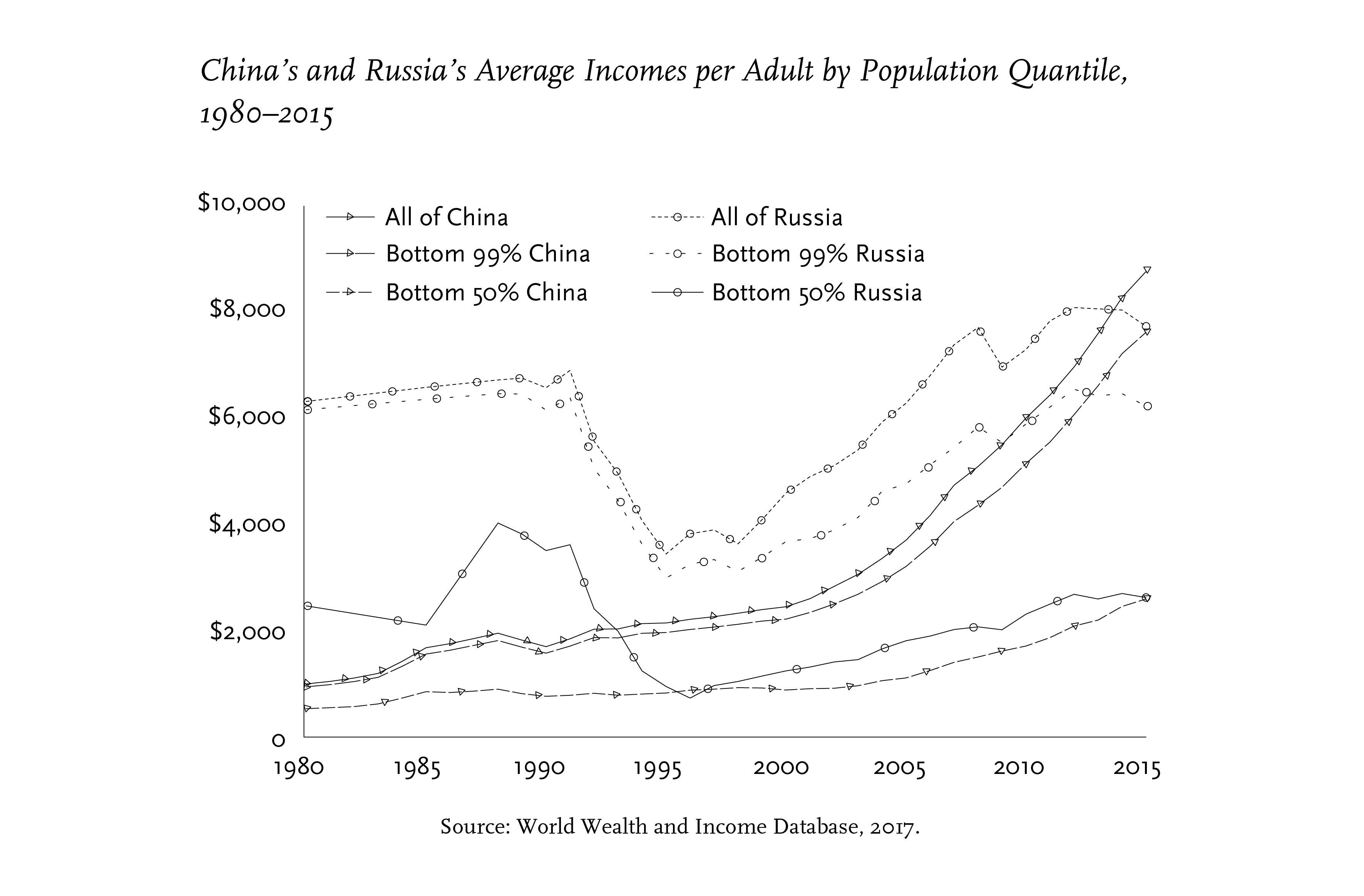

The outcomes are more consistent, however, if we use a different metric—economic inequality. Weber herself is almost exclusively interested in gdp growth and does not explore this aspect. Nevertheless, this becomes strikingly evident in a graph (below) she reproduces from the World Wealth and Income Database, which sets out income trends for different strata of the Russian and Chinese populations between 1980 and 2015. China’s version of state socialism was a good deal more egalitarian than Russia’s, but the transition to capitalism has had the same impact in both countries—a huge increase in the income gap, with the top 1 per cent doing decisively better than the rest. The figure shows just how catastrophic shock therapy was for the entire Russian population, with incomes halving in the space of five years. It was particularly rough for low earners, who saw their income plunge below $1,000 at market-exchange rates, below even the level of the poorest half of the Chinese population.

If we start from the trough of the mid-1990s, which marks the beginning of the intensified capitalist transition in China as well as in Russia, the trends in both countries are strikingly similar. Those at the bottom have seen their incomes inch upward roughly in tandem, while they have watched those at the top grow fabulously wealthy. The close alignment of the income ratios in China and Russia by 2015 suggests that the transition to capitalism does, in fact, have at least one certain outcome, whatever strategies leaders employ to get there. With or without shock therapy, capitalist transformation produces socio-economic polarization, in global conditions the Guanzi economists never knew.