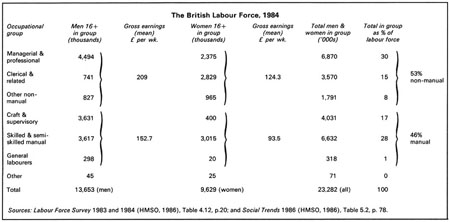

Ellen Meiksins Wood’s review of my book Rethinking Socialism, in her recently published Retreat from Class, and her synthetic remarks on my political views in the concluding chapter are sufficiently well constructed and argued to be plausible, especially to those who have not read my work. footnote1 I am therefore grateful for this opportunity to reply briefly in the pages of New Left Review, on whose editorial committee she serves. I hope to show that her various criticisms, both general and specific, are fundamentally misconceived. But first I would like to outline, with the help of table one, some pertinent facts about the occupational and gender structure of the labour force in Britain, as well as the mean gross weekly earnings of manual and non-manual workers in the spring of 1984.

The Family Expenditure Survey for 1984, based on a sample of 7081 households, allows us further to refine the data in the table.

footnote2

This survey covered households with one or more members in the labour force, but also included these in which one or more members were unemployed or had retired. Of the households sampled nearly 70 per cent had normal gross incomes in excess of £100 per week, while 30 per cent had incomes of £100 or less a week, and 15.5 per cent had normal gross incomes of £60 per week or less. A closer analysis of this income distribution showed what one might expect. In the three lowest income deciles, a large majority of households (83 per cent) were headed by unemployed or retired people. As against this, only a tiny fraction of the poorest 30 per cent of households were headed by people in professional, technical or managerial occupations (a mere 1.3 per cent on average), while

In short, for the latest year for which official data are available, a year in which the crisis of British and world capitalism was still very severe with 3,160,000 people officially unemployed in Britain (and the real figure well over 4 million), there was still a considerable majority of the British labour force with a significant material stake in the system, whatever measure of this is used. Statistical lines are of course always arbitrary, but a variety of lines suffice to indicate the rough orders of magnitude involved. One line could be drawn around those 61/2 million male non-manual workers earning a mean income of £209 per week, another around those 42 per cent of households with gross weekly incomes in excess of £200. More probably, those with a stake in the system should include a considerable proportion of the six million women in occupations with average gross earnings of £124 per week. It should certainly also include 70 or 80 per cent of those seven million men in skilled, semi-skilled and supervisory manual jobs earning a mean weekly income of £153, many of whom would also have wives, sisters or daughters among the 31/2 million women in the same kinds of occupations. Thus, perhaps 20 million of the 23 million people in the British labour force in 1984 were earning enough that despite increasing insecurity of employment, increasing indebtedness and increasing awareness of those 12 or 13 million people in Britain who are in severe and worsening poverty (young people, old people, many black people, many single-parent families, many chronically sick people) they might yet be persuaded—or enough of them might—to allow the Tories another five years of office.

Moreover, as the Household Expenditure Survey shows, the vast bulk of these people are workers, sellers of their labour power on a full or (increasingly) part-time basis. The richest of them own some equity directly, many others have equity investments indirectly through unit trusts, pension funds, building-society and bank accounts.

footnote3

Nearly 11 million of the 18 million household heads in Britain in 1984 were owneroccupiers and for most of them their home represented their only significant capital asset.

footnote4

For all but the very richest, however, loss of paid employment would put all these other income sources at risk, sources which, if not supplemented by a wage or salary, would not in any case allow them or their households to maintain their ‘accustomed’ standard of living for very long. So, despite the rhetoric of the Thatcher

What is the point of all this? Simply that when, in Rethinking Socialism, I speak of the working class or of ‘ordinary people’ it is these 20 million or so people of whom I am speaking, at least in the British case. The book asserts, with an unashamed simple-mindedness, that any form of democratic socialism in Britain will have to win the support, or at least the assent, of such people, people who are still, as the book asserts, ‘neither black, poor nor radical’. Nor is this simply electoral fetishism. I am not asking socialists to concentrate all effort on winning a magical 51 per cent of the electorate to the support of the Labour Party. I made a much broader and much simpler observation—namely, that no attempt at a socialist transformation in Britain, whether attempted after an electoral victory or in any other way, will stand any chance of creating a more genuinely democratic as well as more equal society unless it gains the informed, consistent and persevering support of the British working class as a whole. If one thinks, for example, of this transformation being attempted in the face of virulent us opposition, then a determined, persevering mass support becomes an absolutely essential (though by no means sufficient) condition of its success.

The book then goes on to consider why, or on what basis, such support might be forthcoming and it rejects the conventional Left answer which always focuses, in one way or another, on the material self-interest of the working class. This answer is rejected on the historically conditional grounds that if a socialist transformation in Britain (however gradually or democratically undertaken) involved any degree of economic disruption (and a hostile usa could, for example, guarantee that it would), then short or even medium-term material self-interest would, and should, lead the British working class to withdraw its support from that transformation.

Ellen Meiksins Wood notes that the new ‘true socialism’ (of which I am, apparently, an apostle) ‘tends to take the form of devaluing “crude” material interests as a possible source of positive political impulses’ since it treats ‘“interest” and “morality” as diametrically opposed.’ And she adds, ‘No doubt there are a great many philosophical issues to be debated here.’ You bet there are, and talking vaguely about ‘diametrical opposites’ does not help clarity in debating them. Quite simply, any person, or group of people, may pursue certain political or moral ends or goals, and may, at the same time, seek specific improvement in their own material situation, or support other people seeking such improvements. There is no logical contradiction here, as Meiksins Wood properly stresses. But there may be contradictions in practice in particular historical situations, and without the specification of those conditions or situations, logic in itself will get one nowhere. For example if, in a specific historical situation, it is asserted that A (a specific material