Albert Szymanski’s attempted refutation of our thesis on the reconsolidation of us imperialism presents a ‘summary’ which does not in fact correspond to what we actually argued; offers statistical data that is largely irrelevant to the issues at stake; ignores important aspects of our position; and is based on an inadequate conception of social forces.footnote1

Let us begin with our argument. We did not assert that ‘the usa suffered some relatively minor setbacks around 1970’. On the contrary we pointed out: ‘It was clear that the old basis of American hegemony was cracking, that new alignments were developing and the old basis of doing business on a world scale was coming to an end.’footnote2 (Emphasis added.) Our article then discussed the ‘internal dynamic, political strength and global structural underpinnings which facilitate recovery and reconsolidation of us hegemony in global politics’.footnote3 (Emphasis added.) We argued that us hegemony was based upon the capacities of the American imperial state; the character of class relations within national states; and relations between the us, its erstwhile competitors and the third world.

Many of our propositions have been supported by recent events.footnote4 There has, if anything, been an acceleration of the rate at which countries in the third world, even those with relatively nationalistic governments, are being incorporated into the American Imperium.footnote5 Not only has Japan’s economic and strategic dependence on the United States continued, but in the former case it has increased. Only enormous exports to the us have prevented Japan’s economy from sliding into deeper difficulties. ‘Japan remains firmly subordinate to American imperialism.’footnote6 In the Middle East, Syria has become an agent of reaction, and fear of Iranian imperialism has continued. Thus the United States, even more than in the past, remains the protector of regional stability and the dominant political force.footnote7 We argued that divisions and conflicts within Europe re-emphasize the region’s economic and political dependence upon the us,footnote8 and noted especially conflicts over energy policy. While some progress has been made here, Europe is faced with

It is important to note that we did not deny the serious decline of American hegemony in the late sixties and early seventies. But we did argue that this decline had reached its limit. We observed: ‘Even if the us economy were not almost three times as large as its next largest capitalist competitor . . . its docile labour force and relative abundance of fossil fuel would give it a pre-eminent position in the world capitalist economy. When one also takes into consideration the extreme dependence of the Japanese economy on the outside world and the instability of the eec, its position becomes enviable indeed. This perception itself is becoming a major factor in the world economy. Because the United States is the safest place to invest one’s money, it is, as we have already seen, becoming a magnet for foreign funds . . . Thus the United States, as in the post-war period, is the pre-eminent world banker.’footnote11 (Emphasis added). Perhaps we should have emphasized such words as becomes and becoming in our original article. But we are, at worst, guilty of prematurity. After all, the test of theoretical insight is the ability to explain historical forces before they are fully developed.footnote12

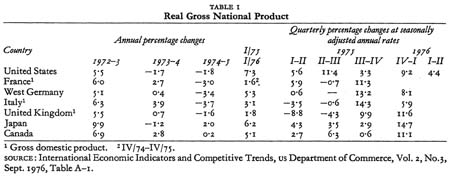

One cannot present persuasive quantitative data on a trend before it is well underway, but recent statistics are consistent with our position. As expected, America’s recovery from its deep recession has preceded that of Europe. However, contrary to the earlier expectations of bourgeois economists, it no longer appears likely that much of Europe will follow the American economic expansion. Thus Business Week recently

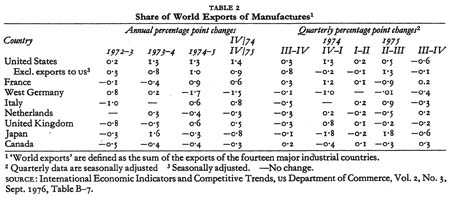

We still lack evidence that ‘the United States, as in the post-war period, is the world banker’.footnote15 Or more accurately, we cannot prove that the decline of the us imperial banking system has ended. But our assertion was based on the not unusual view that industrial, military and financial power are closely related. World financial markets have been in an extraordinary state of flux over the last few years. Nevertheless, Szymanski places enormous importance on unexamined aggregate data—see the discussion following his Tables 7 and 8. Unfortunately for his analysis, flows of capital are greatly influenced by factors whose relationship to underlying economic and social strengths are often indirect or unclear. Thus, for example, the heavy concentration of opec investments in the Euro-dollar market in 1975 reflected the generally higher interest rates in Europe. In the first half of 1976, this ‘trend’ seems to have been reversed. In 1975 there was also an enormous expansion of the Euro-bond market. Why did the United States do so poorly in this market? Was it because of the continued decline of the American Imperium? We doubt it. It had much more to do with the failure of the us Senate to exempt foreigners from withholding taxes on interest earned from us bonds.footnote16

Again, we are not impressed by the International Monetary Fund’s August projections for 1976. Instead, we will continue to agree with Business Week’s assessment that ‘trends now at work in the world have greatly strengthened the competitive position of the us economy, which suggests the reversal in the direction of investment flows that began last year will continue’.footnote17 (Emphasis added.) We are presently studying changes in world capital markets and the world banking system. When we have enough information over a long enough period of time to establish a trend, we will report back. In the meantime, we will stay with our theoretically based position and avoid the pitfalls of naïve empiricism.